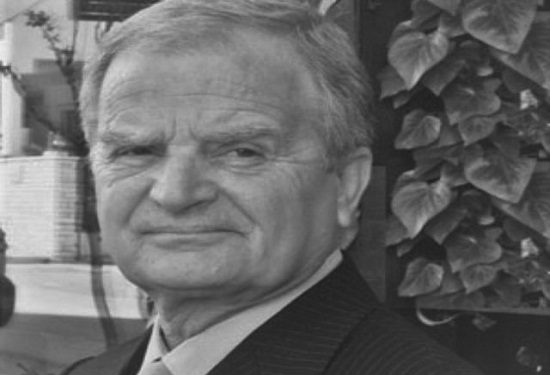

About the novel “The Lion in the Cage,” by author Shpendi Topollaj, dedicated to the life of Lieutenant General Abaz Fejzo

Memorie.al / Recently, a severe illness gripped me from corner to corner and broke me down rib by rib, taking me right to the door of the other world, and surprisingly, I returned for a little while longer. In the first phase of the illness, I had a several-day improvement, and precisely at this time, I read one of Shpendi Topollaj’s books, “The Lion in the Cage.” I mentally thanked the writer for the pleasure he gave me during this difficult period of my life, where, among other things, I was also psychologically much burdened. I read it without putting the book down, for a series of reasons: the first is that the author of the book is my friend, and I certainly expected something good and beautiful from him.

I was convinced that the book was masterfully written, as I know the talent of the hand that wrote it, having read several other books by him. To be honest, I also had a specific concern: how the figure of a general with extraordinary values, who lived, fought, worked, and was tragically punished in our time, was treated.

A general who, like many others, put everything they had at the service of the homeland, but without being able to complete their contribution. They initially showcased their skills and capabilities in the war and thanks to the bravery they displayed, they earned the golden plaques of the highest rank in the army. Besides being baptized in commanding combat formations in the fire of battles for freedom, they were educated in famous military schools and academies, and later distinguished themselves for commanding troops and modernizing the armed forces. They demonstrated a very high professional level, and over the years, their talent stood out in the tactical-operational and strategic exercises of the army.

But above all, their loyalty to their Homeland was noticed. Therefore, they strived with all their might to be as devoted as possible to it, constantly cultivating them. Such was the main character of this very engaging book, the Commander of Armored Vehicles, Abaz Fejzo.

From a very young age, he left the shepherd’s crook in his native village, Tragjas of patriotic traditions, and wandered off to be educated, to become a valuable person in life. But he also interrupted his studies to take up a rifle longer than himself. At that time, there were no ranks, but ideals.

That’s why I had this concern; how the author had treated the growth of this young man, who, despite his good but also tragic fate, became a representative of almost all those heroes and generals who were at the head of the army and whom the iron broom of the time’s madness reduced them and their families to the worst possible state.

However, a master knows how to balance the work properly and emerge reliably on the path he chooses and that the reader expects. Shpendi did the same with the figure of General Abaz, where ultimately the author was not much interested in the ranks and insignia, but in the life of the man who honestly and devotedly carried out the assigned duties.

Today, this may sound somewhat sentimental, even I would say romantic and unbelievable, but this was our reality during those years, and this writer has presented it to us so beautifully and artistically in his book. I think this was the difficulty, but also the greatest merit of this novel.

I did not know Abaz Fejzo personally. I met him two or three times at various official ceremonies, we greeted each other and that was it, but I must say I heard a lot about him. People often talked about his broad culture, and not just military culture, that he possessed, and about the foreign languages he knew. His quickness and readiness to answer any kind of problem posed for discussion were mentioned. As far as I can remember, he was small in stature, but his word was heavy and weighed. This gave him a lot of authority, but also respect in the eyes of subordinates and colleagues. I found these qualities of his that I mentioned materialized in this book dedicated to him.

The hero of the novel, after a life and war full of brilliance, ends tragically, like all his comrades of his kind, or at least, like most of them. It is a great value of this author that he knows how to capture and treat such delicate topics and manages to artistically expose the crimes of communism. What happened in our country over the years is truly unimaginable, macabre, and anti-human.

People were run through the mincer, and as if they were Lushnjë leeks, their heads were cut off, and all this with the absurd justification that; this is how the Party becomes stronger. No one, of course, swallowed this heartless paradox, but many valuable human lives suffered, and many innocent families were sent to internment, destroyed, and vegetated with mutilated souls in wretched conditions.

We encounter plenty of scenes from their life, where they were forced to stay for a very long time, in this book. The author has wonderfully and painfully described their suffering and psychology to us. He has been careful to present them to us as they were: people of great dignity and unbent.

Abaz’s wife, his daughters Eliza and Pranvera, are portrayed with great love. The death of their sister, Tamara, leaving behind her young son, creates great sadness and grief. And imagine how grieving Abaz’s own heart is, the lion locked in the dark and cold cells of Burrel prison.

Shpendi, as in his other stories, novellas, and novels, makes us live with the worries and sufferings of the heroes of this novel. By reading the book, intentionally or unintentionally, we participate in their pain. Whether we want to or not, we silently mourn their fate, pouring out tears along with them.

The events make your flesh crawl, revolt you, and amidst a lump that gathers in your throat, they make you think. Even though I had known for a long time what happened to the honorable Fejzo family, it still felt like I was hearing it for the first time. And I wondered: how was it possible for these things to happen?

And I recalled that ominous Plenum of 1980, when Enver Hoxha, who was chairing it, as usual twisting the chain around his finger, from left to right and vice-versa, uttered his sclerotic and old rascal’s phrase: “…as if we don’t know who Beqir Balluku was, he was a s…-of-a-b…” and continued further with his nonsense. But why was the former Minister of Defense like that for Enver?! Was it because before he even turned 20, he lined up in the guerrilla units, risking his life several times, and then leading important units of the National Liberation Army, or because in 1947–’48, he drew the line at the oak tree for the Yugoslav divisions that Tito wanted to deploy in Korça, finally realizing his dream of turning Albania into the seventh Republic of Yugoslavia, or because in August 1960, when the Soviet leaders provoked him, he stood up in his defense? Well, for all these and more, since this is not the place to say them, was Beqir Balluku a s…-of-a-b… who should be executed? I do not intend to defend Beqir Balluku and his comrades. I do not do this as much as I intend to, and even more so, I cannot. Now I speak in function of what the book describes. They were people, Albanians, who spared nothing for their country, just like Abaz Fejzo did. I knew most of them personally. They were people with a glorious past who still carried the scars of war on their bodies.

It is not excluded that over the years, they liked comfort. The privileges given to them may have softened them somewhat, flattering them, but I do not think they ever intended to overthrow Enver Hoxha. Or that they were against the socialist and communist system that we claimed to be building. On the contrary, I want to believe that they thought the good things came from Enver and Marxism-Leninism. I had family members, or very close relatives, who held high positions in the army. They were ready for any sacrifice, because with the Party and Enver, they identified the Homeland.

And Enver repaid them: “You are a putschist, be executed!” “You are arrogant, be imprisoned!” “You have knowledge of black material, be interned!” “You have eaten more lambs than you should, be expelled from the army.” “You other one did this and that…,” and fantasy and malice took flight. And all of them, heads bowed like sheep, went where he ordered. Where did they leave all the bravery and manliness of the war? Where did they take their pride? I want you to understand me correctly! Now it is easy to speak, but back then the matter was completely different. But something must be done so that things are clarified, generations learn, and history does not repeat itself, even though I myself am convinced that this historical madness will never happen again.

The truth is that even though all this time has passed, there are still question marks and subjectivism towards these figures. Our literature has dealt little with them. But it has plenty of material, often grotesque, to be encouraged to write. Everyone remembers the absurdity of the accusation against Deputy Minister of Defense Nazar Berberi, in the early 1980s, that he had allegedly produced a cane-pistol which he would gift to Mehmet Shehu, so that when he went for a walk with Enver, fap… he would turn it into a weapon to kill him.

Shpendi is perhaps one of the rare ones who has defined the role and place of this layer who believed, fought, sacrificed, studied, worked with dedication and loyalty, but also suffered quite severely, hence being disappointed like few others. I say like few others, because the injustice and cruelty with which the system’s opponents were struck needs no comment. The horrors they experienced are countless, and they deserve the greatest respect and deepest gratitude of all our people. But those who stood by that regime without any hesitation, thinking they were doing something good and melting away their lives for it, with their end and the end of their families, are the most powerful accusation, the most stubborn self-exposure of the primitive and barbaric Albanian communism that even ate its own children.

In the historical novel “The Lion in the Cage,” the author Shpendi Topollaj has described Abaz Fejzo’s life with great love, a characteristic feature throughout the entirety of his abundant literary work. Having been an officer himself and having suffered like him, like his father, also an officer, perhaps Shpendi was the most suitable writer to deal with such figures and lives.

And he has achieved complete success in this by no means easy task. He, as he himself admits, knew the hero little or not at all; he met him and only had lunch once. This is little, very little, to erect a monument to him, with the accuracy of his physique, character, mind, cultural and professional knowledge, or with the courage to openly admit mistakes, no matter how insignificant they were.

The process of the metamorphosis of the convictions of Abaz and his condemned comrades was also complicated. But with the infallible intuition of the now experienced writer, he has managed to give us Abaz Fejzo so truthfully that one of my friends, Sazan Bitri, rightly said; “Abazi finished the academy with a gold medal, and Shpendi also wrote his life with a golden pen.”

By way of illustration, I quote Abaz’s meditation in the solitude of his cell: “Now I have to fight to save my honor. Until yesterday, I fought for the honor of the Homeland, but that is apparently not enough to show the individual’s loyalty and devotion. This test is also needed. And I will pass it. I know it’s hard to get out of this mess alive, but I will keep my honor untouched. The body will die one day, but honor will not. It lives forever. Let them remember me as I truly was. Nothing can be hidden from history. Shame will cover the one who reduced us to this. This has happened over the centuries to many, many others, but in the end, everyone has gotten the name they deserve. And the one who did this wickedness to us, his comrades, will be called Nero, and generations will mock him. Although the opposite should happen: Nero should be called Enver. Even those who are acting like this towards us today will turn their backs when he is gone. Perhaps Hitler had a reason, after the Stauffenberg plot, to become a savage and force Rommel to kill himself. But with us, how can one act this way? How can a person become like this? At least let them enforce what the law allows.”

While reading this book, I got the impression that the hero and the author have many things in common. Both spent most of their lives, as I said, in the army. One is from Tragjas of Labëria, and the other from Kolonja (with a Vlora mother), tough places these, and with people who are somewhat stern, but with great contributions in favor of the national cause. Both are military men with distinguished abilities and great love for the book. Consequently, both of them did not view great culture as an external ornament or decoration, but as a necessity, to put it in the interest of work and life, that is, of society.

It is worth emphasizing the range of their knowledge of art, history, literature, and especially their knowledge of the world of antiquity, so much so that it seemed to me that a competition was taking place between the book’s hero and its author. A competition of who would tell more about mythological heroes, but not fairy tales from the past, but to have them as a parallel to the times we live in. I recall here Abaz’s dialogues with the Director of the Museum, the Library, or in prison, with Pjetër Arbnori, Uran Kalakulla, Halim Ramohito, etc., or the letter he sends to his beloved wife, Filloreta. And this adds to the importance of both Abaz Fejzo and this novel itself, where everything is done with a sense of measure and placed where it should be.

With this novel, a very important work is added to Albanian literature. Specialists will speak about it. As for the style, the polished phrase, the chosen word, the literary figuration, and the endless amount of information we find here, I don’t want to elaborate, as they are already known by all those who have read Shpendi Topollaj’s works in poetry, prose, or literary criticism.

I have nothing left but to congratulate the author, wish him further success, and thank him with gratitude for being there for me with his novel during a difficult time, when I greatly needed spiritual medicine, which significantly eased the pains of the treacherous disease. Memorie.al