From Dom Zef Simoni

Part thirteen

Memorie.al publishes an unknown study by Dom Zef Simoni, titled “The Persecution of the Catholic Church in Albania from 1944 to 1990,” in which the Catholic cleric, originally from the city of Shkodra, who suffered for years in the prisons of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime and was consecrated Bishop by the head of the Holy See, Pope John Paul II, on April 25, 1993, after describing a brief history of the Catholic Clergy in Albania, dwells extensively on the persecution suffered by the Catholic Church under the communist regime, from 1944 to 1990. Dom Zef Simoni’s full study begins with the attempts by the communist government in Tirana immediately after the end of the War to detach the Catholic Church from the Vatican, first by preventing the Apostolic Delegate, Monsignor Leone G.B. Nigris, from returning to Albania after his visit to the Pope in the Vatican in 1945, and then with pressures and threats against Monsignor Frano Gjini, Gaspër Thaçi, and Vinçens Prenushti, who sharply rejected Enver Hoxha’s “offer” and were consequently executed by him, as well as the tragic fate of many other clerics who were arrested, tortured, and sentenced to imprisonment, such as: Dom Ndoc Nikaj, Dom Mikel Koliqi, Father Mark Harapi, Father Agustin Ashiku, Father Marjan Prela, Father1 Rrok Gurashi, Dom Jak Zekaj, Dom Nikollë Lasku, Dom Rrok Frisku, Dom Ndue Soku, Dom Vlash Muçaj, Dom Pal Gjini, Fra Zef Pllumi, Dom Zef Shtufi, Dom Prenkë Qefalija, Dom Nikoll Shelqeti, Dom Ndré Lufi, Dom Mark Bicaj, Dom Ndoc Sahatçija, Dom Ejëll Deda, Father Karlo Serreqi, Dom Tomë Laca, Dom Loro Nodaj, Dom Pashko Muzhani, etc.

The Testimony of the Former Bishop of Shkodër (Continued)

I was sure that this denunciation would never bring any consequences to them. They were two individuals who had truly provoked me, and whom I, knowing them, had not responded to. They had spoken to me, but I had not spoken to them. As soon as I started talking, only about these two, the investigator did not want to know anything about them. “Others, others,” the investigator demanded. I had also spoken with others, but I thank God that not a word slipped from my mouth. “We will address this problem again next time, after you think about it in your room,” he told me. As soon as I went to the room, I thought there might be a recording device, and speaking to myself, lightly, in a low voice, I said: “I am amazed, I have nothing to say.”

The next time, which was the following day, they informed me that they were closing the investigation that day. They had formulated the charges. All nonsense. All nothing. All fairy tales. They told me there were four. They were the article on non-denunciation, and the one on agitation and propaganda through writing. “The others,” they said, “we will remove,” and these were the article on organization, which was completed by the appointment of the “new diocesan council,” and my appointment as Vicar General, and the article on religious services, which the constitution had not yet included. According to these, I was convicted of hostile activity. The accusations were true, but in the accusations, rights and freedoms were violated. It was the triumph of violence.

The Trial, April 26, 1977

One morning, the investigator notified me in my cell that I would appear in court that day. “The trial will be held inside the Branch,” he told me, “with closed doors. It is a special trial. This was decided because of the relations the Church had with the state.” It was April 26, 1977. They were putting the flock on trial too. Where is the flock? Where is their shepherd? Instead of the Monsignor being at the Church of Our Lady of Good Counsel, at 10 AM, on the occasion of her feast, together with the clergy, to celebrate the Holy Mass, in the presence of thousands of devout people from the city and villages, filling the Shrine, the square, and the castle slope, he is in the courtroom, made of bone and skin, like a corpse on its feet. That’s what they had done to me too. This was the popular religious song: “In our difficulties and troubles! / The Sons of Our Lady seek relief.”

The centuries of our destruction had gathered in the hardships and times an exposed history, releasing the venom of a furious fanaticism against everything holy, and especially the Catholic faith.

Four of us were on trial: Monsignor Ernest Çoba, Bishop of Shkodër, Monsignor Lec Sahatçia, Ordinary of the Abbey of Mirdita, Dom Kolec Toni, priest, member of the diocesan council, and I, with the duty of Vicar General. We were all dressed in uniform clothes, a canvas the color of flesh, buttoned up; as a deep Oriental Communist irony, they dressed us in this terrible day, taking us to a large courtroom, bound in chains and accompanied by two police officers each. For the four of us, there were a total of eight police officers, plus two more.

We were told to speak freely. “You can express your thoughts, as you are calm people and will not break the rules.”

For them, we were the complete opposite of them, representing only a world that must be destroyed, a deep and obscurantist world, continuous enemies of the purity of history, inspirers of oppression, intrigues, enemies of culture and science. The court entered the hall with the chairman, two members, and the prosecutor took his place. We stood up, out of respect. The trial began at 9 AM. Three days, 9 AM to 1 PM. Their attack began. The first two days were spent questioning the Monsignor, first with the accusation of his secret relations with the Holy See, through the Italian Embassy, and his relations with Dom Deda and Dom Ivo. Then Monsignor Lec Sahatçia, accused of having participated directly in the murder of Bardhok Biba, in August 1949, and forms of agitation and propaganda, and Dom Koleci and I, for not denouncing the Monsignor’s relations with the Holy See and for agitation and propaganda. And I also for writing.

The accusations had no value, no fault, but our fault lay in our very existence. They wanted to achieve the complete annihilation of the priesthood and faith. For them, we represented all the evil. This is what they thought. The trial had begun, it was underway. We spoke all our words honestly, without passion, and in a concrete way. The Monsignor’s trial lasted two mornings. They were slowly peeling him away. Regarding all the activity he had exercised, in connection with the Holy See, and Dom Dedë Mala, he explained that it was linked to his conscience. Despite the attacks they made on Monsignor Lec Sahatçia, the chairman of the court and the prosecutor, he affirmed that he had been aware of his murder, but absolutely not that he had prepared anything in this murder, and that he was in a complicated situation under those circumstances.

“Even today,” he said, “regarding these matters, it is a mystery to me.” The prosecutor’s anger was furious. “Admit the truth, or your head will roll. You are under the power of the party.” Dom Kolec Toni declared bravely that; “private economy does not exist, but everything is state-owned, and that is why we are here.” They dealt with me more because I had not denounced the writings, which were religious in content and against materialism, dictatorship, and the class struggle. To the question of the chairman of the court: “why I had not denounced,” I told them I was against denunciation. And I continued by saying that: “if someone provokes me, I tell him it’s better not to speak to me, than to accept coming and denouncing. Then, why do you ask me to denounce, since these issues were ours. I have written against you because I have a Catholic upbringing and secondly, because I was very angry about the actions you have done in Albania, especially the closing of the churches.”

In some of the prosecutor’s talks, the work of violence was expressed in a synthetic and triumphant way, which does not allow you to move, and they wanted us to be in chains, because our presence, for them, was an open church, a sermon still on earth. The regime and the judicial body had a single head. Enver wanted only unity and ideological work, making all those responsible for the tasks of annihilation act with conviction that this is how the country has found its way. This class struggle is of the unity-violence type. The prosecutor raised his voice many times, his main duty and that of prosecutors, from Koçi Xoxe, Aranit Çela, and hundreds in districts and cities, was to be ready for attacks. With the stance of a wolf, swelling up to tear its prey, the burden fell on him to triumph over the class enemies, happy that he worked with such certainty for the party line, loyal to it until the end. The chairman of the court, the honor of justice, who weighs everything with the brain of the class, maintains a balance, like an insatiable conqueror.

He is the main tool of the apparatus, which removes and transfers people’s heads, and sends the majority to places of suffering and death, without a scruple, wanting to see everything finished, to put an end to generations, without any old generation, without any past truth. This trial also had witnesses, eleven of them, and was aggravated by their inaccuracies. May God forgive them, for there were also slanders? The third day also had the afternoon, for the verdict to be given. And for this, the doors were opened, where many officials of the Shkodër Branch participated. Monsignor Çoba was sentenced to 25 years, Monsignor Lec Sahatçia to 20 years, Dom Kolec Toni to 13 years, and I to 15 years. The trial ended with much applause for “the justice of the party, against the furious enemies of the people’s power.” The history of the Branches, the kingdom of death and blood, of thirst only for crimes, which had officially begun in the first weeks of forty-four, now gave a kind of end to the ecclesiastical hierarchy. There was no worse day for the people and history.

After some time, other clerics would also be arrested, such as: Father Anton Luli, Dom Pjetër Gruda, Father Leon Kabashi, Dom Nikollë Gjini, and Father Gjergj Vata.

The Monsignor let out a light sound, asking for absolution. We all did the same, towards each other. And we, with handcuffs on our hands, all disappeared, and I never saw the Monsignor again. He would undergo other spiritual, moral, and physical sufferings. We would receive the news about him that he died in the hospital in Tirana, after a puncture they had supposedly performed to relieve his pain and stop his heart. Their plan was put into effect on January 12, 1980, the feast of Saint Ernest, whose name the Monsignor prayed to. After the trial, we fell into calm, a silence, to quickly embark on a new, long road of life. We can say that everything had ended, and the people were running through their troubles to earn a miserable piece of bread, dissolved and bewildered in the space of great suffering. A young, sullen, and calm policeman, with a natural kindness, Hamzai, asked, when I went out for cleaning, how much I had been sentenced to. “They gave me the 15,” was my reply. He was annoyed and took it as a mockery. But he did not speak.

Spaç Prison, May 13, 1977

It was May 16, a Monday, when they sent me to Tirana. I left the investigation cells, from that cruel room, where I spent almost eleven months, with so much pain, suffering, torture, and isolation. I left the Branch and got into a bus, where there were 10 people. I also met Dom Kolec. I leave my city for a long time, leaving behind my elderly mother and sacrificing sister, my brother, who would suffer from sickness and prison. All new wounds. Two days before I arrived at the Tirana depot, where all the convicts from various Branches were gathered to be distributed to various units, Gjergj had been sent to the Ballsh Unit. They only called one prison: Burrel. After ten days, which we spent in the Tirana depot, again by bus, together with Dom Kolec Toni, seventeen people in total, we were sent to Unit 303 of Spaç, to live a life alive and in misery.

This closed, dark machine inside seemed like something that connects to nothing. Every reality is original. Every car could drive from Tirana to Spaç, but all with differences. This machine has its own specific features. It has in common that it drives like all the others. But what is unique is that it does not drive like the others. It has speed even in curves, it shakes, it has cruelty, it has malice. There are seventeen people with their hands bound in chains. To the one who managed to see something through some small holes during its journey, and to me, on this sunny day, the earth seemed so merciless, with those fast, fixed views. You could not distinguish mountain and field under these circumstances. It gave the impression of a chaos, like an absurdity in existence. Only light is seen, mixed with great darkness, with a color close to the darkness and an abyss of time, of slavery. We seemed like living beings emerged from the grave, seeing each other, having been thrown into an infinity of futility.

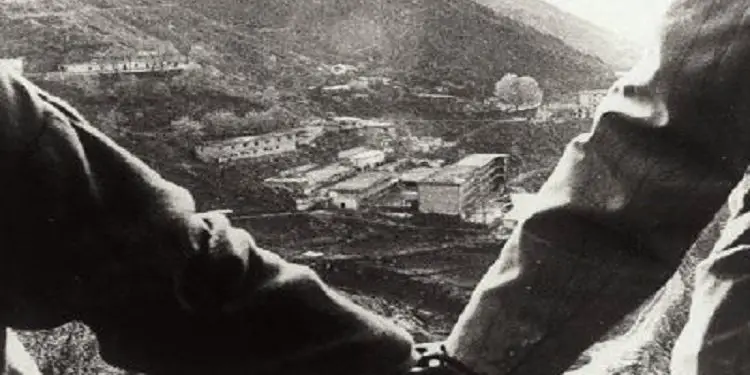

It was this Friday when we arrived close to two o’clock in the afternoon, the large gate of the unit opened, and immediately closed. I felt and embraced the long isolation. I entered without knowing when I would leave! Will I leave?! This was a momentary thing, and with the future remaining in darkness, secrecy, the path was opened and the conviction strengthened, for those forces that man has to resist. Here I have to spend the years. In God’s hands. The camp guards who served there are just guards; loyalists of the government, courts, and the dictator. They are the working tools of that machine, the adored dictatorship that lives with these forces, and who did the special work of oppression up close, and presented its very bad side, in that place surrounded by barren mountains, and barbed wire, near a very often dry stream, over which eagles circled in the limited sky, over our living and dead heads. It was truly a natural prison as well.

These guards had a consistent demeanor. They were calm; spoke little, because they were also ordered not to engage in conversations with the prisoners, with these “enemies,” the “bad seed in socialist Albania.” It was a refined Mirdita police force. When they had to administer punishment, besides the punishment that the prison had after the revolt that occurred in 1973, the police would form groups or squads to beat them, until they were tired, on the body of the poor prisoner, often an unparalleled hero. And this brutal violence happened because they did not complete the quota in the mine, whose sight alone terrified you, or if the police found you trying to put something small in your mouth. Two military guards in green uniforms slowly called roll, calmly looking each of us in the face, as we answered. They sent us with a prisoner in their service, to a warehouse, to get the brick-colored uniform, a straw mattress, and four old blankets, difficult to touch by hand, so much disgust they gave off.

I and the majority of prisoners slept in those for twelve years, because the privileged ones in their service had new ones.

We received new uniforms every year, but now clothes with mattress stripes. All shaved, they took us down some stone steps to the camp, which had the shape of a cone. In the two courtyards, hundreds of prisoners were waiting for us. We embraced acquaintances and the three priests we found there, Dom Ndoc Sahatçia, Dom Ernest Troshani, and Dom Martin Trushi. There were also people from Shkodër, and among them, Zef Ashta, with academic degrees and who had spent almost thirty years in prison, with whom we would stay every day, a calm and pleasant man, who died a few years later on a May Day. There we found Toni Andrachio, Monsignor Ernest Çoba’s nephew, an exemplary young man in prison, rare for his good character traits, intelligence, and Christian virtues. A group of Mirdita men, each better than the last, beloved and loyal people.

And when Nikollë Prenga would arrive from Burrel prison, a prominent man in the camps, this group of Mirdita men would be strengthened. There were also good men from the northern mountains, and many villagers from our areas, with proper demeanor: people of faith and virtue. Slowly getting to know the camp, we would find young men from Vlora and the southern regions of Albania, selected, determined, brave, and courageous. I saw many new faces in this dangerous camp of the revolt, which occurred four years before my arrival. There was still one year left to complete the official sentence of the punished camp. But the punishment and terror I found continued even stronger.

On the occasion of the revolt, it was said that the Prime Minister himself had participated in suppressing it, four people were executed, and more than eighty were arrested, terribly tortured, and convicted. All convicts, without exception, had to participate in the mine work, even those who were sick with all kinds of diseases, even those with high fever. As soon as we were dressed and quickly settled in the rooms, where fifty-two people lived in each room, on three floors, and where I settled on the lower part of the third floor of the building, we were notified to complete some formalities, registrations, and orders given to us by the camp commander.

“The Technical Office” in Spaç

The camp was directed by the command, but there was also an office in the camp consisting of three prisoners, approved by the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and these people linked and resolved everything with the command, and were attached to it like flesh to bone, and the command, the Technical Office, and the prisoners formed a real trio. This second office is called; the Technical Office. The brain office. This directs the work of the mine, the underground and the land surrounded by mines, a place with risks of collapse, where accidents and deaths occurred, the number of which had reached over one hundred people. In such cases, the commander would hypocritically urge with pain that they should be careful at work: “when you enter the underground,” and on the other hand, he rigorously demanded the completion of the norm without fail, because it is the law. “You must work, to atone for your faults, not faults, but crimes that you have committed against the people’s power.”

In the mine, there could be heroes, who were dirtied with mud and cleaned themselves with determination. The Technical Office there monitored the camp discipline. It is the center of the network, of all official and secret movements. Being the center of information and liaison, which organizes espionage and sets it in motion in this regime of entanglement, these are highly trusted people of the command. They are prisoners and commanders in an oppression that takes many forms. Just like in the Orient. Albania that organizes espionage in prison, outside, and outside Albania, even in the Vatican.

Zyhdi Çitaku

And a prisoner, who was in their service, Zyhdi Çitaku, for many years, traveling through many places in Europe where Albanians were located, had recruited people into the service of the regime. And since he had made some mistakes outside, in connection with their plan, when he arrived in Albania, they quickly arrested him and severely punished him. In prison, he behaved well. Saturday and Sunday seemed somewhat cheerful, in the beautiful May sun. Thus several weeks passed for me, but I was very tired and had strong dizziness, especially when climbing the stairs, leaning on the railings, when I went to the room. But when you start to get used to it and the prison makes you its own, then its life begins, and slowly the acquaintance with other sufferings and misfortunes. It was called: the camp of enemies. It had many people with culture, but not like those who were in the first years, where the cream of the nation’s culture and genuine intellectuals were located, with degrees from universities in Europe and America, where the camps and units showed no signs of espionage, except rarely someone who was immediately discovered.

The people were more educated during the period of socialism, and some educated in socialist countries of Europe, engineers, military personnel, from the system, many people who could not be called political figures, but rather those who had violated, according to the government, the laws of the constitution. The constitution, called the most democratic in the world, which without exaggeration had put one-third of the Albanian population in prisons.

It was necessary to talk very carefully with each other about issues concerning political life. Many sought to find a companion, to discuss various problems related to life and the necessity of your life. We would talk, but mostly about events happening in the world and within our borders, information from newspapers that entered the camp, and radio news, which deafened you from 6 AM and throughout the day. We would talk carefully, because the espionage network worked there, very dangerous, which could quickly bring you a new arrest. If they convicted you ten years the first time, for agitation and propaganda, the new sentence could be ten more years, and then thirty, forty years. And depending on the case, even death inside. How many people died inside the prisons?!

Spaç: 1700 Prisoners, Chinese Politics!

The prisoners observe everything. The prison bus brought other prisoners every ten days, including former party and government cadres, whom Enver bound alive, and whose number multiplied within the year. The camp had a force of about one thousand seven hundred people. The vast majority were young. They were brought by Chinese politics, agitation and propaganda, escape attempts, revisionist cadres, whom the party was throwing out with kicks, sending them to the firing squad and to prisons. All these people, the destructive constitution called: “traitors of the homeland.” We had the bad name; we were called “traitors.” This title did not weigh on us, but made us laugh with our irony, as to where this concept of traitor had reached, in the Albania of the class struggle?! Those who arrived by prison bus brought news that the Internal Branches were filled with arrested people. They were waiting to go to trial. The camp was not asleep. It had energetic and powerful people, full of courage and a kind of pride. The day, the weeks, the months passed quickly. The year never ended. Life had great torments, of the time and the place where they were./Memorie.al

![“The ensemble, led by saxophonist M. Murthi, violinist M. Tare, [with] S. Reka on accordion and piano, [and] saxophonist S. Selmani, were…”/ The unknown history of the “Dajti” orchestra during the communist regime.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/admin-ajax-3-350x250.jpg)

![“In an attempt to rescue one another, 10 workers were poisoned, but besides the brigadier, [another] 6 also died…”/ The secret document of June 11, 1979, is revealed, regarding the deaths of 6 employees at the Metallurgy Plant.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/maxresdefault-350x250.jpg)