– CREATING ART IN ENVER HOXHA’S ALBANIA –

Memorie.al/“Socialist realism did not describe life as it was, but as it should be.” In 1952, just a few years after the communist regime had begun in Albania; Dictator Enver Hoxha announced the founding of the “New Albania” Film Studio, a film production studio that would produce the entire national cinema until the end of the regime in 1990. The early attention of the Communist Party of Albania regarding the pedagogical importance of art and cinema in producing a new national culture was clearly evident in the internal workings of the Film Studio, where state ministers and the Central Committee had the final say in the selection of film crews and thematic aspects. In 1970, after graduating from the Institute of Arts in Tirana, Arben Basha started working as a scenographer at the studio.

The walls of Basha’s personal studio in Tirana are now filled with expressionist paintings, a style he would not have been allowed to paint before 1990. It is now nearly 50 years since the beginning of his career. When asked if he was aware that he was making propaganda during Enver Hoxha’s time, Basha answered slowly but honestly. “Yes. Yes, of course I knew this. But there was no other way to do it. You had to work. You had to eat. You had a family.”

A Changing Regime

In Enver Hoxha’s Albania, artistic production was always closely linked to the internal conflicts of the state. Isa Blumi, Associate Professor at Stockholm University and a specialist on Albania, says that whenever Hoxha’s regime changed its orientation, whether by turning its back on the USSR or Mao’s China, there was a purge of the existing political elite, and consequently new dictates were imposed on cultural life.

By 1961, after the breakdown of relations with the Soviet Union, Hoxha had ensured that Albania was on its way to becoming the most isolated country in the world. His first action was to develop the ideological campaign of “communist education,” from which would emerge “a new person with new ideas, with outstanding virtues and high morals.” In his 1965 speech, Hoxha declared writers and artists as “educators of the masses.”

Albanian socialist realist art, largely like socialist realist art in general, emerged in service of political ideology, but it was also unique as a consequence of its more extreme isolationism compared to the rest of the Eastern Bloc. Albania’s socialist realism was concerned with illustrating Albania as if it were on the verge of a new era, and there were several ‘new eras’ during Hoxha’s 40-year rule. After each reorientation, those who had remained loyal to the previous generation of leadership were now considered dangerous by the state.

When Basha started working at the Film Studio in 1970, it was during a time now remembered as a period of ‘liberalism’. This seemingly more open period ended with the campaign of 1973, which marked the beginning of the Albanian Cinema purges, during which many artists were accused of being anti-conformist and some were sentenced to imprisonment, internment, and even execution. While many remember this time as the beginning of a new era of horrific state repression against cultural life, Blumi disagrees with this narrative.

“The so-called period of liberalism is not like that at all,” he explains. “We are simply dealing with a generation of artists who worked for the regime at that time, who then either left or were forced to publicly renounce their past.”

“THEY WERE VICTIMS OF CHANGING TIMES, NOT OF DIVISIVE MORALITY OR ETHICS.”

Professor Isa Blumi speaks about the artists involved in the “Purge of the Liberals” in 1973.

Blumi notes that the mischaracterization of this period is a tendency of Albania’s revisionist history which continues to be written by those who survived to experience 1990, and suffered as a consequence of the 1973 power transition. “These artists would claim, as victims of Hoxha’s regime, that they are liberals; certainly since they were imprisoned in 1973 during the purge, they should be considered by us, in retrospect, as good artists against Hoxha, who courageously challenged the regime that trampled on them,” he says. “This is nonsense. They were conformists and followed party orders from the late 1960s, and they simply found themselves in the midst of an internal power transition.”

More than being persecuted because they represented some dissident tendency, Blumi emphasizes that many artists were persecuted simply because they were protagonists of the past generation of Hoxha’s regime elites, and their work had become outdated and was contrary to the regime’s new standards. “[They] were victims of changing times, not of divisive morality or ethics,” he considers.

The “Worker” as the Ideal Citizen

The central figure of Albanian society, and consequently of socialist realist art, was the “Worker,” the heroic figure who worked day and night to build a new Albania. It was partly the careful creation of the “Worker” as an ideal model through which the regime monopolized its violent power. Adhering to the “Worker” model meant gaining the protection of the State. The essence, according to Blumi, was “behave like this worker, and you too will eat.”

Artistic illustrations were among the most important means through which these violent messages were conveyed. Basha, whose paintings were several times criticized by gallery officials, says it wasn’t enough to just depict workers in the works, but “you also had to be careful about how these workers looked. Were they muscular and healthy? Did they show any signs of dissatisfaction?”

It was precisely this advance fear over every detail of the painting that clouded Basha’s career under Hoxha’s regime. He says it was impossible for a painting to be accepted in a gallery if even one element could be suspected of being non-conformist in breaking the stylistic rules.

As for what these ‘rules’ entailed, Basha says they ranged from the colors used to the time and day the painting depicted. Bright colors translated as optimism for the nation’s future, and thus workers were often depicted with a daytime background, “under the socialist sun,” Basha says with a smile, quoting one of his past art critics. On the other hand, dark colors were cause for suspicion.

Exhibition Politics

In 1986, a painting by Basha was rejected from an exhibition because his theme didn’t seem ‘optimistic’ enough about the Communist Party’s ability to make Albania great.

However, just a few years later, in the early nineties, when the regime was coming to an end, Basha says he had completed a painting showing a girl and a boy along a railway, joyfully emerging from a tunnel towards the light. He was implicitly celebrating the arrival of democracy, but even then, gallery officials were concerned with his illustration of communism as a dark time, and they rejected this painting. “I made a mistake and destroyed it,” he says, “I was afraid at that time. I didn’t want to end up in prison, where I saw many people ending up.”

Frustrated, Basha distanced himself from political paintings for a while and became a landscape painter. “With landscapes, no one would ask me why I painted the tree red, or why it was distorted. But if I continued to paint portraits, they would check me for every possible detail.”

The first time a painting by Basha was accepted for exhibition at the National Gallery was in a group exhibition with Edi Hila and Edison Gjergo in 1972, the last year before the regime’s ties with the destructive Chinese leadership began to crumble. Basha says that despite the attention the exhibition drew from the gallery and art critics, he was afraid to give interviews at the time. Looking back from this distance, he wonders if this is what saved him back then.

By the mid-1970s, painters began to be punished for anti-conformism. Edison Gjergo was imprisoned, and Edi Hila was interned, while Basha escaped. “I went home and burned ten of my paintings,” he says.

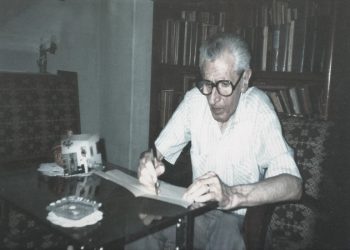

Despite the fact that many artists remember Hoxha’s time with sadness, there are some who would defend the merits of the work done during that period. One of them is Zef Shoshi, famous for his portrait of Enver Hoxha. Shoshi still works every day in his large studio on the top floor of his building near Medreseja Square in Tirana, an area where many artists settled in the 1970s.

“Everyone says ‘dictatorship, dictatorship,’ but from that dictatorship came some truly valuable works. Naturally, they served an ideology, but there are still paintings that are completely realistic, which you cannot characterize as socialist,” says Shoshi, citing as an example the mural at the National Historical Museum in Tirana.

The paintings hanging in Shoshi’s studio are a testament to his long-standing dedication to this tradition. Describing him as an artist “shaped by the regime,” it is clear that Shoshi rarely felt the need to distance himself from it, given how few of his post-regime works have changed in terms of themes, circumstances, and style. This, according to Shoshi, made it difficult for him to integrate into the art world after the 1990s, and he still struggles to find his place, now living from various commissions.

Since the early days when he visited the Zadrima region in Albania in 1955 and sketched peasants as they worked, the central subjects of Shoshi’s paintings have been people engaged in daily activities. “Naturally,” he says, “I also had the desire to do works that are a bit different, but I have continued to treat my works and their subjects in a realistic style. While back then I painted the people of Zadrima working, now I have freed them from work or present them differently, but they remain my focus. They are the same subjects I continue to work with.”

“I AM NOT AT ALL SORRY THAT I MADE PORTRAITS OF ENVER HOXHA. THEY ARE HISTORICAL WORKS. THE TIME WILL COME WHEN PEOPLE WILL LOOK AT THOSE PORTRAITS AND WILL NOT IMMEDIATELY THINK ‘HE PAINTED THE DICTATOR’ AND REJECT THEM.”

Zef Shoshi

When asked how he feels about being known as a painter of the regime, Shoshi replied: “All painters in every century have worked for their Kings. Velasquez made several portraits of King Philip IV, and is now known as one of the most distinguished realist painters in the world.”

“I am not at all sorry that I made portraits of Enver Hoxha,” Shoshi continues, “They are historical works. The time will come when people will look at those portraits and will not immediately think ‘he painted the dictator’ and reject them.”

According to Shoshi, the devaluation of socialist realist art is actually a function of time. Instead of “freeing themselves from politics” and appreciating art as art, many continue to consider his works, especially the portraits of Enver Hoxha, as nothing more than propaganda.

This is the reason for Shoshi’s recent frustration. He had an exhibition at the National Gallery of Kosovo in April of this year, where he was supposed to display his portrait of Enver Hoxha, but it was removed from the exhibition at the last moment. “The media started criticizing the gallery,” Shoshi explains. “Saying ‘look, Zef Shoshi is sending his portrait of Enver Hoxha to Kosovo.’ So, the portrait was not exhibited. The political perspective remains, so more time needs to pass for people to let go of this attitude.”

Painting the Emancipation of Women

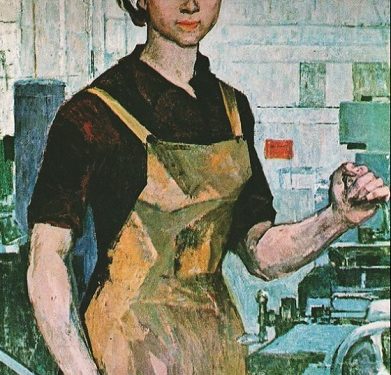

Both Shoshi and Basha are known for their portraits of women during Albania’s campaign for the “Emancipation of Women,” which was based on the idea that women’s liberation was achieved only through their inclusion in a new and unified working class.

Paintings of women working were an important installation in the iconography of that period, including Shoshi’s 1969 painting titled “The Milling Machine Operator” (“Tornitorja”).

When asked if he intended any political message when painting this portrait, Shoshi seemed aware that his painting undoubtedly served a certain policy, but he sees that policy as separate from the art itself, for which he accepts responsibility. “As in the case of other artists, I worked with themes that the time demanded,” he explains.

Basha’s portrait depicting a young girl from the same period, titled “I Will Write” (“Do të shkruaj”), was brought to the National Gallery but was never exhibited. While most paintings of that time showed young girls working in fields or factories, Basha painted a girl at her school desk, with a blank sheet of paper in front of her, and a pencil in her hand.

“They accused me of hermeticism when I tried to exhibit the painting for the first time in the ’70s. They considered the meaning wasn’t clear, and the Party always wanted the meaning to be clear,” says Basha.

Asked about the title, Basha replied: “I wanted to paint her as a powerful witness, as someone looking at the country and saying: ‘Will you do well for this country? I will write. Will you do harm to this country? I will write.'”

However, the pressure Basha felt during that time to conform to the Party’s aesthetic standards is clearly visible in the painting’s background, where a bustling industrial landscape filled with grain silos and factories can be seen tinged with a golden color. “In this painting there are clear socialist realist themes. I was young, just out of school, and still believed in part of that idea,” Basha admits.

After the turmoil of the mid-1970s that ended with the imprisonment of many artists, Basha’s paintings disappeared, and resurfaced in 2000, when the National Gallery in Tirana established a permanent exhibition of paintings from the period.

Albania’s Communist Cinema

Many of the ideological requirements Basha had to adhere to in his paintings similarly applied to the films he worked on as part of the Film Studio.

The first film Basha was involved in was titled “The Call” (“Thirrja”) (1976), which dealt with the journey of an intellectual professor who went to work in a village, where he was confronted with the backward mentality of the villagers. The actress who played the role of the Party secretary, Basha says, was Justina Alia, who had sung a song praising liberalism at the Song Festival in Tirana in the early ’70s, before the power transition in 1973.

In 1975, a month after filming began; Party officials violently removed Alia from the role, because the song she had sung a few years earlier was now considered anti-conformist. She was later banned from acting and singing.

“That was Enver Hoxha,” Basha says with a grimace.

In the early 1990s, as the regime was coming to an end, there were no longer the same restrictions on cultural production as in previous decades, but the transition to democracy was clouded with uncertainty and filmmakers were still afraid of persecution.

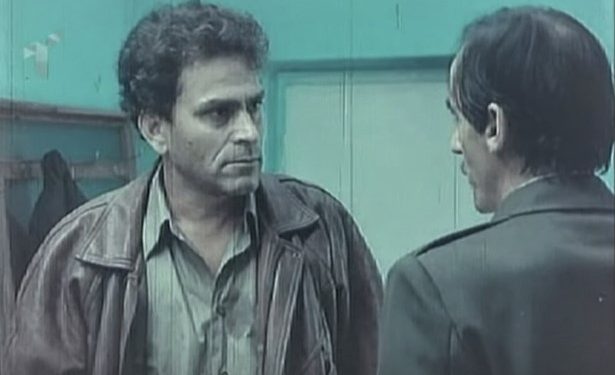

The film Basha was working on at that time, “Death of the Horse” (“Vdekja e kalit”) (1992), ended with the protagonist being unjustly denounced by the Party and sent to prison. “I said to the director, shall we add another episode, as if democracy has come? And he, after prison, gets out,” Basha reveals.

The scene Basha had envisioned showed the protagonist walking through the streets of Tirana, watching the pro-democracy protests, and eventually encountering the Party official who had sent him to prison, who was now a candidate in the new democracy. “Anyway, it was a very sad final scene, but it showed the reality.”

When Basha mentioned this to the young director, he received a negative response. The director insisted that the script end as it was, telling Basha to write the scene himself if he wanted to take responsibility for it.

“He was afraid,” said Basha. “But by 1992, things had improved – there was no longer a Party Commission evaluating films. And so, we shot the scene. And I still believe it is the most beautiful scene of the entire film.”

Memory Questioned

The definition of art’s purpose, according to Enver Hoxha, was to reflect social relations – that in art one would feel “the pulse of life and battle” of the people. While Basha, whose paintings occasionally dealt with political issues, would not necessarily disagree with such a statement, he undoubtedly considers that this is not what socialist realism did.

“It would be wrong to see the art of that period as a reflection of what Albania was like,” says Basha. “In truth, it was the way Albania should have been in the eyes of the totalitarian doctrine of communism. The reality was very different – and we were witnesses to it, those of us who worked at the Film Studio. As a painter, while you could paint the happy peasant with a pickaxe in his hand, in reality he had no bread to eat at home.”

This is a reality that even someone like Shoshi cannot deny. “Yes, we were poor,” says Shoshi, “but we were simple. The time will come when the things that happened will begin to be appreciated, not just the bad things. That regime also created many good things, and we have inherited them all.”

While distancing his work from the politics of the time, Shoshi’s recounting of his experiences cannot hide his admiration for Enver Hoxha, which, unlike Basha’s harrowing accounts, is a feeling he shares along with many others.

Despite creating numerous portraits of Hoxha, Shoshi was never ordered to do so, and had almost no contact with him throughout his life. His only significant encounter with Hoxha, he says, was during his youth as a pioneer, when he visited Hoxha’s birthplace, Gjirokastra, and showed the leader his drawings.

Apart from this meeting, Shoshi says he only saw Hoxha viewing gallery exhibitions, and mentions a particular exhibition Hoxha attended. “I extended my hand, and he told me, ‘stay as young as you are,'” Shoshi recalls, his eyes welling up.

Nearly thirty years after the end of the regime, nostalgia like Shoshi’s still remains, and the memory of Hoxha continues to produce emotional effects. In many ways, it seems as if Shoshi and Basha lived parallel realities, far from the worst reality of that time, and yet it all speaks to a clear division of experiences, between those who were devout followers of Hoxha’s ‘good working class,’ and those who risked exclusion from it.

In post-communist Albania, where those victimized by communism live alongside their executors, the impossibility of dialogue that could bring these two closed realities closer makes the issue of memory difficult to address.

“For many, the regime happened alongside their youth,” says Basha. “And when we remember our youth, we tend to think of its beauties.” /Memorie.al

![“Count Durazzo and Mozart discussed this piece, as a few years prior he had attempted to stage it in the Theaters of Vienna; he even [discussed it] with Rousseau…” / The unknown history of the famous Durazzo family.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/collagemozart_Durazzo-2-350x250.jpg)