By Ahmet Bushati

Part thirty-nine

Memorie.al/ After the flag was altered in 1944 with the addition of the communist star, Shkodra transformed into a center of resistance against the regime, paying a high price for its tradition of freedom. By April 1945, high school students, already feeling betrayed by the promises of the war, gathered to oppose the new terror that imprisoned and killed innocent people. Communism turned Kosovo into a province of Yugoslavia, while Shkodra was punished for its “historical crime”- its defiance against invaders. The “Postriba Movement” became a tool to suppress all dissent, plunging the city into an unprecedented spiral of suffering: imprisonments, executions, and the destruction of families. The high school students, alongside citizens, became symbols of resistance, while some “young communists” turned into tools of the State Security, leading to expulsions, imprisonments, and internments.

Four times, Shkodra rose in armed rebellion, but history forgot these battles. This book is written to remember the countless prisoners, the tortured, the killed, and the parents who suffered in silence. It is a warning against dictatorship and a plea for future generations not to forget the sacrifices made for freedom.

Continued from the previous issue

In the Footsteps of a Diary

The first person Nush Simoni would introduce to me from a distance was Pjerin Kçira, with the modest nickname “Shkoza”, who was Nush’s closest friend, whom he loved and respected as much as he did, despite the fact that they were friends and peers. Pjerin – like me – was kept alone in a dungeon that was opposite Nush’s and diagonally opposite mine. Pjerin, on that occasion, after asking me about my physical condition, expressed regret and pain for the suffering I had endured. Ever since that night, he would say to me: “What’s wrong with you?” and then he would ask me: “Do you remember me?” and when I answered “No, I’ve never seen you,” – he would continue, surprised: “But how is it possible that you don’t remember me, when in fact I shot you without knowing what you did and how much it hurt me, but there was nothing I could do”?!

Pjerini was right to be surprised that I didn’t remember him and the torture incident, since he didn’t know my unconscious state at that time. From Nush that night I learned that the prisoners, taking advantage of the somewhat lenient attitude of the police and their superiors, had been talking to each other for several days and those they had called me several times, but that I had not listened to them. Today, I can’t find those beautiful words that would be able to express the great pleasure I felt from my first contacts, especially with Nush. I could not sleep because of joy. It seemed to me that on that occasion I was leaving behind the solitude of a tomb, inside which I had been different, that that night I was entering the living world of people, where there was room for me too.

Even during the next day, I would continue with the impressions of the conversations of the previous night, as well as with the joyful idea that in the evening, I would talk again with that Nushi. The second night, Nushi, in conversation with me, began to introduce me to the prisoners, cell by cell, name by name, starting from the one with no. 1 and continuing, and when he reached that no. 7, where Refik Bushati was, probably together with Emil Miloti, I interrupted him, telling him to connect me with Refik, which Nushi did immediately. Refik, for his part, although he was more protected than the others, as he was at the end of the corridor that was with the dungeon, fell short and only spoke two words, two words that, in terms of content, would have been more valuable than all the conversations I had had with others until then.

Asked to inform me about what was most important to me, he said: “Ahmet, Bardhosh Dani has been killed and Simja is fine”, that’s all Refik Bushati said and I suddenly felt my heart beating so hard, just like there was a foreign object inside my chest. How was it possible that Bardhosh had been killed, something I could never have imagined?! My legs immediately gave out, I interrupted my conversation with Nushi and with tears in my eyes, I collapsed onto the bed, remembering Bardhosh with longing, his life as an only son, his seventeen years of age, his family with deepest sorrow, but also his enthusiasm for the mission he had undertaken.

There were two pieces of news with opposite contents, and the truth that the pain of Bardhosh’s death, once and for all, eclipsed and greatly diminished the joy I would experience later, from the certainty that Simja was free. I must admit that along with the deepest shock over the death of Bardhosh – with whom we had spent several years of childhood as brothers and our two families as if they had been part of the same house – but later, as if the wave of grief over Bardhosh’s death had somehow subsided, I began to feel a sense of pride, albeit somewhat nervous, for the fact that the anti-communist resistance of Shkodra students was being affirmed not only with work and prison, but also with blood.

When we went to the New Prison, I would learn the dynamics of the murder of Bardhosh Dani, Brahim Dërgut and Mark Cacë. When the “Albanian Effort” group had been exposed, these three had decided to cross the border at all costs, but when they noticed that the border was guarded by armed forces, they would return to Shkodra once more, and after securing a weapon within the day, through Brahim Dërgut, they would head back to the border, where ultimately, betrayed by a certain Sait Mustafet from Vithgar of Anës se Mali, they would be killed, responding with fire.

It is appropriate here to mention a friend of mine since we were children, Nexhat Meta, who had been arrested during those days, having been a teacher somewhere near Vukli in Greater Malcia. Since the dungeons were full of prisoners, Nexhat, bound hand and foot with chains, had been thrown at the end of the corridor, towards us. From that time on, the duty of surveillance of the police would be taken over by Nexhat, who, whenever the police started to move, would give a signal by banging the chains. Poor Nexhat would pay tenfold for using this “code”, which was soon discovered by the police, who would not believe Nexhat when he told them that; “he moved the chains because of the pain they caused him in his hands and feet”. The prisoner, as if for a call that comes naturally from within, finds special pleasure in every sacrifice he makes in the name of solidarity with his fellow sufferers. Nexhat Meta was one of them.

Nush Simoni, pierce the wall that separated him from me!

There were several nights in a row, starting from midnight onwards, on the wall that separated me from Nush, at the very point that corresponded to one of my clothes, when I was lying on the mattress, from time to time I was disturbed by a harsh scratching that could be heard on the wall, or as if it were an annoying rustling of wood, like the ones we used to hear during the summer under the wooden floors of our old houses. And one night in particular, after a week of constant worry, I would feel that erosion working even more fiercely and persistently, and even more closely, until suddenly, thanks to the misfortune and circumstances that give prisoners patience and inventive power, that wire thread would manage, after a week of work, to finally triumphantly cross the wall that separated Nush’s dungeon from mine, at which point he would immediately call out to me in a low voice: “Ahmet, Ahmet”!

How happy we were when we started talking! We were talking as if on the telephone: when one spoke with his lips gathered around the small arch of the hole, the other on the other side of the wall would have his ear to the hole, and so on, as if in turn. In the same cell with Nushi was another prisoner, a certain Gjon Bushit, young and dark-skinned, gentle and always smiling and, as it seemed, under Nushi’s absolute power.

Two would be the most important events that I learned that night from Nushi: Enver Hoxha had been in a state of discord with Yugoslavia since June, that is, six or seven months earlier, and that about two months earlier, he had announced the famous so-called “turnaround”, by which he sought to atone for his sins and those of the party he led before the people, blaming all of them on his subordinate, Koçi Xoxe, who until then had been Minister of the Interior and second in command. From Nushi, I finally solved for the first time the riddle of the cessation of torture, as well as the reason for the peaceful spirit that Sirri Carçani’s visit had had, a few days earlier.

That night, I talked with Nushi until late. Among other things, I learned from him that my friends were no longer there, nor were the other prisoners from the previous five or six months, who had been transferred to other prisons, mainly to the “Gestapo” prison, in order to free up space in this Sigurimi prison for those recently arrested. Among others, the name of Mark Shllaku also appeared, about whom we have briefly spoken once, and taking advantage of the occasion, we also point out that, while Mark himself, after much torture, had been sentenced to death and shot, his brother Hila, having stepped on his brother’s blood, out of fear and pressure from the Sigurimi, had agreed to become a spy, arriving to treacherously penetrate the Mirakaj fugitive group, which operated in the mountains of Puka.

I learned from Nushi that Pretash Nika, a former officer who had just returned from the war, was still there, along with his still undeveloped son, Nika, a wonderful boy and friend of ours, later. There was also another former officer from Malcije, the old communist Gjeto Keqi, who, as we have shown, had participated in the Spanish War and, from his dungeon, whenever he found the opportunity, would recite his satirical poems to us, with which he ironized, not without talent, his former comrades in war, turning us into careerists and, “with epaulettes on our shoulders”. As long as Koçi Xoxe had been in power, Gjeto Keqi would be accused of having connections with the “traitor” Mehmet Shehu, and when after a few days the latter became Minister of the Interior, Gjeto Keqi would be accused of being a Titoist and of having connections with Koçi Xoxe!

One day, Gjetoja, while arguing fiercely with Rasim Deda, – who at that time had replaced Lilo Zeneli as head of the Sigurimi – among other things, would speak to him very indignantly: “I have suffered the prisons of Franco and, after that, that of Italian fascism, but with your prisons, there is nothing in the world”! Rasim, as if in agreement with the politics of the party and the position he held, would answer: “Then understand, Gjeto Keqi, that this is the red terror”! Gjetoja, who still had enough time to answer him as he wanted, would remind him of Lenin’s fable about the fox, who he did not kill when it shed tears, and would end the “debate” with him, shouting loudly that; “Titoism will triumph one day in Albania too”.

There was Gjon Ljarja, who had graduated a year earlier, and who, being very gentle by nature, wanted to believe that he had been excluded from politics. There were students Tom Sheldija, as well as musician Preng Jakova, who, taking advantage of the turn, would be released along with four other prisoners, among whom were also some students. There was a certain Mirash Gjeket, from the Dedajs of Malsija e Madhe, as well as the poor Zef Bardhoku, who once, as a young partisan, had been known for his courage and had emerged from the war as an officer with the rank of second lieutenant. There were also Gjovalin Mazrreku and Lin Sallaku, who, together with Zefi, Nushi and Pjerin Kçirë, would comprise the group known as Pjerin Kçirës, who had first been young communists and, finally, with Pjerin at the head, had organized themselves into a group against that government.

There were Rasim Hebovia and Qemal Dibra, former partisans Haki Dibra and Gani Ymeri, as well as guitarist Emil Miloti, who had recently returned from Austria, where he had been pursuing university studies. Likewise there was Hilmi Kamata, a former young ballist and close friend of Ruzhdi Rroji, arrested precisely for the connection he had had with him during the time he had been underground. Todi Ruho from Pogradec was also there, a former partisan who, in the difficult winter of 1944, had served as a courier for Enver Hoxha, when he, together with Dushan Mugosha and Miladin Popovic, were in a cave on the Gramoz Mountain. He had been arrested here in Shkodra, where he had continued to be head of the recruitment office.

There was also the young Leonard Pema, whom Corporal Qaniu would beat hard two or three times with a belt, after he had caught him talking to others. There was also another young man, Isa Kraja, as well as Kolec Pikolini, who, as we have noted above, were part of the so-called “Social-Democrat” group, with Mark Shllaku as its leader. There was also Professor Zyhdi Sokoli and many others whose names Nushi did not know, as well as a spy named Ndue Marku, a former forestry worker, whom the Sigurimi would walk from one dungeon to another, for their own purposes. A Sigurimi officer, Palaçon Ndue Marku, would put him in another dungeon, kicking and insulting him, in order to make him trustworthy to the inmates of the dungeon where he was being taken as a spy. Where the two corridors of the prison joined, in the center, right behind the back of the policeman on duty with the bench, inside a dungeon without a number on the dark side, was Bajram Bajraktari, Muharrem Bajraktari’s younger brother.

The student Mikel Muzhani, who at that time was being held tied up somewhere in the corridor, would tell how a policeman from Lujjan would secretly introduce boiled chestnuts to him every day. I asked Nushi if a Malsorian of a more or less large age and build was also there, whom I had followed with sympathy for his noble appearance and his rather dignified attitude months earlier, from my cell no. 9. Nushi denied that such a man was there. I would learn his name later in prison: he had been called Keq Sadiku and, from Reç, he had been known and respected everywhere in Malci, as a very wise man, who had been constantly called by the people for various trials, as if he had been their lawyer.

The former partisans, who had once found food and shelter in Keq Sadiku, as they had in almost no other place, not only abandoned him during the days of their “delirium”, but one day they would put him in prison together with Taron, his son, for whom the prison guards would not find words to highlight his wonderful qualities. As for even more ingratitude and cruel murder, even for Keq Sadiku’s own father, the Security in Koplik, led by a certain Et’hem Barbullushi, would kill his son, along with Dom Zef Sirdani, Tom Çuni and Nikë Marku, on the evening of the first day of arrest, and their bodies would be thrown into a W.C. pit of the Security Branch in Koplik.

We talked at length that night with Nushi, until we parted very late, leaving to meet the next evening, just before the lights were turned on for dinner. Nushi instructed me that before I went to sleep, to prepare a kind of masking cap for the hole, which he wanted to consist of a mixture of soap with a little wool taken from the pillow, to have the shape of a thin pancake and, so that it would not stand out from the rest of the wall, to sprinkle it with a little of the plaster dust that fell down the wall from the blows that he, especially, in the form of messages for me, exerted on it. The Sigurimi would never discover this hole during our stay there, even though they had been following its trail, so much so that one night Ali Xhunga himself would stand for hours behind my door, but without success, because I had noticed his presence from the beginning, from the shadow his two legs cast under the door of the dungeon.

When the next evening, the lights were turned on, at the appointed time for dinner, I would be forced by Nushi to move as far away from the hole as possible and to pose with a plank of wood against the wall, where Nushi, like the eye of a camera, would look at me, and then quickly say to me as if in surprise: “You’re young and you’re good too! I’ll take the bad, stay like that for a while, because I had fun with you”! More than two or three times that night, Nushi would repeat to me: “By Christ, where would I see you with that beard and walking on your hands and knees on the ground, and taking your breath away, I remember you were about seventy years old”!

A Night in the Gestapo Prison and the Miraculous Dawn of a Morning

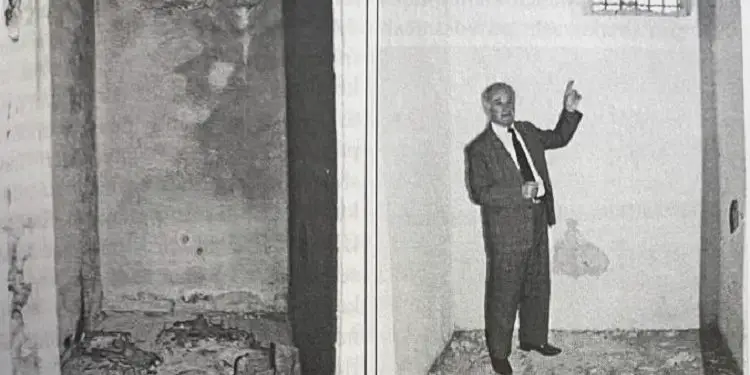

One day, cold and winter, but sunny, when with one policeman in front and another behind, they took me out of the Sigurimi prison onto the main road, without knowing where they were taking me. We turned left and quickly at the crossroads, we turned right towards “Perashi”. We had only walked another fifty meters when we entered a short alley on the right, at the end of which a large gate appeared, which would be that of the so-called “Gestapo” prison, known in Shkodra by this name, since the time of the Germans, who turned that large residential building, with some modifications that they had made to it, into a prison.

In this prison were kept those prisoners who had completed their investigation, where they would usually stay for months and months, and sometimes even a year or two, awaiting trial. As we passed its courtyard, we found ourselves inside a hallway, where for several minutes the personnel of that prison did not know where to put me, until Ali Xhunga came there, to confront me with a prisoner. They temporarily took me into the dark depths of a basement, where it took me several minutes to regain my sight, and when I saw that all around the place where I was sitting, there were only pieces of wood and planks thrown around for burning, and that right next to me, there were some puppies sitting quietly, which I had almost stepped on.

After staying there for about two hours, they took me upstairs to a large room with a wooden floor and ceiling, where I was impressed by its size and abundant light. That room was completely bare and, except for a reinforced door with a large latch at the back and a hatch that opened in it, there was nothing else to take for a prison cell, which Ali Xhunga would shortly improvise in the investigation office, having put inside it for that occasion only a rather random table and chair, which it seems were used by the unassuming head of that prison himself. When Ali Xhunga finished with me, I, as I had been accustomed to a small dungeon for a year, that room seemed to me as big as a football field.

The afternoon was short and night was fast approaching. The police were not coming to take me. My mind was on the prison in Sigurim, on my dark cell, one of the darkest in that prison, to which I had become so accustomed. Above all, my mind was on the hole with Nushi and on the conversations with the other prisoners. But when the dark face with thick eyebrows of a familiar-looking man from Shkodra, who was in charge there and had the rank of aspirant, appeared at the counter, and who on that occasion was holding out a piece of black bread to me, I regretfully gave up hope of returning to my cell that night.

Inside this large room there was an electric light, which, for safety, never went out during the night, while outside, there was complete darkness. No matter what happened to me and how tired I was, I lay down to sleep on the only bed the room had, which stretched under its three windows. For once, sleep came quickly, but very quickly and even more slowly, from the cold of the night.

Someday, finally, the last hours of that long winter night would pass, so that the morning, a frosty morning, but with good weather, would begin to dawn, at first as if gray and with a little fog, to be cleared little by little by a light that burned like gold, that was emerging imperceptibly and with great grace from behind the ridge of that mountain, which had the name “Shit of Hymel”, a light that was always spreading more and more peacefully, far across the horizon.

The sun had not yet risen on that mountaintop when, down in the prison yard, I would hear the voices of two men coming out of the prison building, talking to each other. One had been a policeman, while the other, a prisoner with a broom and bucket in his hand, which I recognized immediately: Visho Barbullushi himself, our neighbor and cousin, who very soon began sweeping the yard. Memorie.al