By ELAINE SCIOLINO

Memorie.al / When the new head of the Albanian delegation to the United Nations, Bashkim Pitarka, arrived at a lunch given at the apartment of the head of the French delegation, he seemed agitated as he looked at the three American diplomats. “I will not shake hands with the Americans and the Russians,” the Albanian diplomat said loudly and clearly. “I have been ordered not to.” Joseph V. Reed, the deputy head of the American delegation, extended his hand as a “member of the human race,” but Pitarka turned away and, nervous about the reserved reception, seemed certain that they had not been seated in a dismissive row in the dining room.

Some delicate actions in diplomacy are resolved through connections via countries that do not have formal relations. The United States, like other countries, uses complicated arrangements, which vary according to the degree of friendship or even practical needs. For example, Washington was represented in Iran through the Swiss Embassy at the time the Islamic radicals occupied the American Embassy in 1979. Due to Iranian intentions and fears for their safety, none of the American diplomats worked there anymore. In Washington, Iran is technically represented by the Algerian Embassy, but it also operates with offices in several cities. The United States allows Iranians to work there to cooperate with the requests of partners of hundreds of Iranians in the United States of America. Iranians have represented Tehran in Washington.

They were equipped with passports or residence permits. These channels usually do not function fully, because Iran was suspicious of Swiss neutrality. During the negotiations last week for the release of the “Wall Street Journal” correspondent, Gerald F. Seib, the Swiss authorities were unable to get any response from the offices of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Turkey and Pakistan, which have good relations with both sides, helped realize this agreement.

The United States of America severed diplomatic relations with Lebanon after a crowd of people burned the American Embassy in 1979, and Belgium represented the interests of that country. Anti-American demonstrators often marched in front of the Belgian Embassy in Tripoli.

In the case of Albania, which excludes any contact with either superpower, and several other governments that the United States of America does not recognize, for example, North Korea, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Angola, without formal ties, relations are represented through third-party states.

But American and Vietnamese officials meet regularly in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, where they discuss the fate of Americans missing since the time of the Vietnam War. Angola is another delicate case. State Department officials admitted that only an informal agreement with Western embassies helped protect American citizens there.

In Cuba, American business is again involved through an interests section under Swiss circumstances and care, which operates more like an embassy. It has about 20 American diplomats inside. Havana and Washington have used their regional interests for negotiations on objectives such as the punishment of plane hijackers and the emigration of Cubans to the United States of America.

But some issues, like the Cuban troops in Angola, have been discussed at the highest levels. In Nicaragua and Afghanistan, although Washington also finances anti-government rebels, it still maintains diplomatic relations and an embassy. But the ambassador’s post has been vacant in Kabul since 1979, when the American ambassador, Adolph Dubs, was murdered.

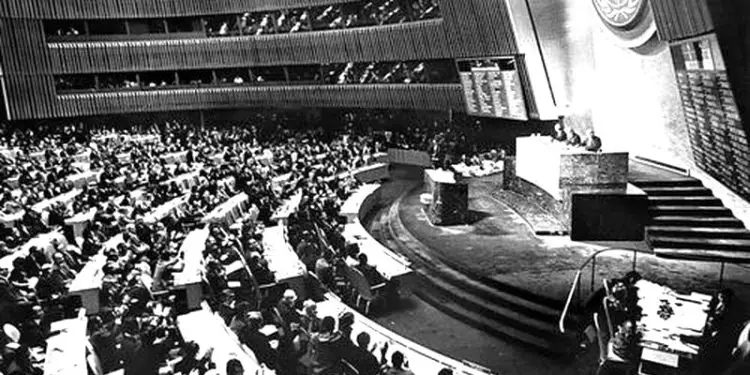

Perhaps the most suitable venue for connections between countries that had hostility, or no relations, was the United Nations, where many countries kept their representatives. Discussions on re-establishing relations between the United States and Mongolia last month were led by the head of the American delegation, Vernon A. Walters, and the deputy head, Herbert S. Okun, who spoke Russian, the language mostly used by the overwhelming majority of Mongolian diplomats.

State Department matters were governed by detailed instructions setting out the protocol for officials meeting with diplomats from adversary countries. “I nod to them twice,” he says, “When they don’t react, I withdraw.”

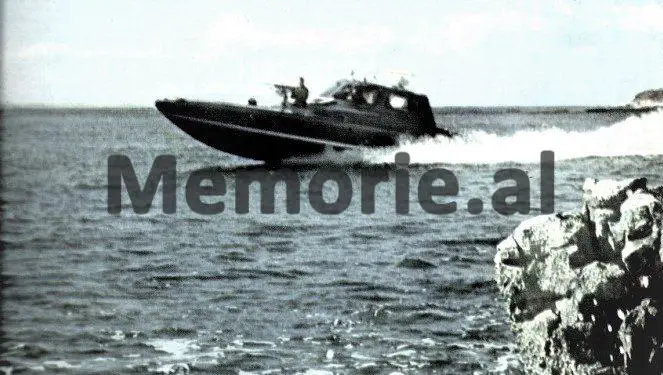

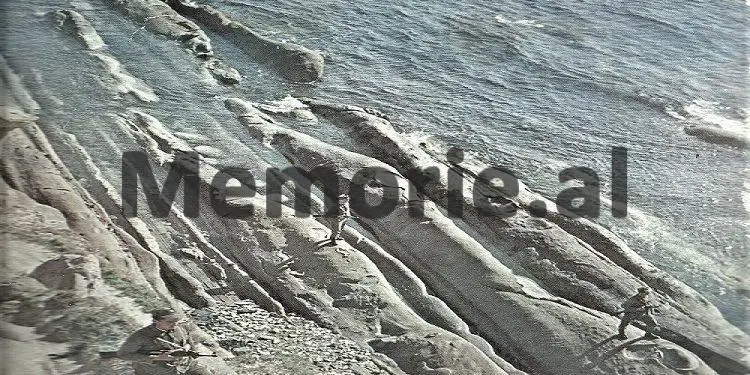

The Yacht Rescue, Interpretations of “Thawing Ice”

The rescue and release of an American yacht with four people on board by the Albanian authorities brought a strange confusion to official Washington in June 1987. Since the rupture of diplomatic relations, there had been no sign of rapprochement.

The provision of assistance and their release without any problem brought different reactions among the American authorities, some of whom interpreted it as a sign of the “thawing of the ice” between the two countries.

The entire event and the interpretations related to it, which occurred in June 1987, are brought in the next article of the “New York Times” that the newspaper offers to readers, which also discusses speculation about a possible opening of Albania to the West, as well as the different opinions of various diplomats. Memorie.al