By Robert Kostaq Cipo

The first part

– With the blessing of the Deputy Prime Minister Andon Pano, the director Stefan Prifti, I permanently exclude the students from all the schools of Albania; R. Cipo, R. Çelo, A. Benussi, G. Karapici, R. Karapici, K. Xoxa, B. Çano, Th. Zhitom e, Th. Marry-!

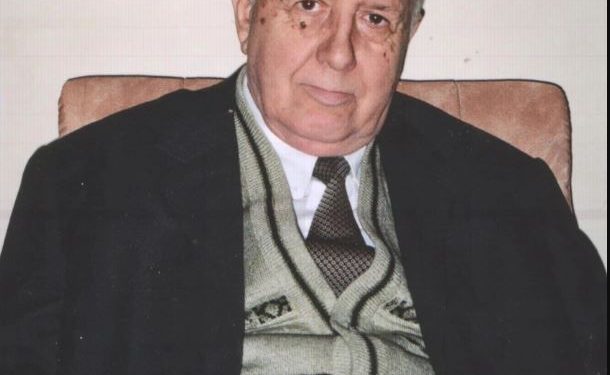

Memorie.al / Linda in Korçë on Tuesday, September 16, 1930, at 10 o’clock in the morning. My parents were, Kostaq Cipo, son of Simon Cipo and Agnia (Juvani) Cipo, and Margarita (Papajani) Cipo, housewife, daughter of Doctor Filip Papajani and Angjeliqì (Kostantinescu) Papajani, housewife. When I was born, my father was a professor of Albanian Language and Literature, as well as of other literatures, except French, at the National, Albanian-French High School in Korça, while Dr. Filip Papajani was the only doctor in the Pogradec district, until in the liberation of Albania, patriot of the Independence period, writer and poet also mentioned in the Albanian Encyclopedic Dictionary.

I must clarify that my father was Elbasanas, born there in 1892, but after graduating from the Faculty of Philology at the University of Rome in 1921, he returned to Albania and was appointed a professor at the “Normal” School of Elbasan and from there he transferred to the Gymnasium of Shkodra and, later at the Albanian-French National High School in Korça. For my name, my own father became the initiator, who, when I was born, was precisely explaining the period of the Norman invasions in Europe and Albania in Lice. He liked the name Robert from Robert Guiskardi, who at the head of his Normans, came to Durrës, where he fought several battles. In that period, as far as I remember, I seem to have been the first Robert in Korça and perhaps the first in Albania.

Immediately, other families also ran to give this name to their children. As soon as the telegram arrived in Elbasan, announcing the birth of the first son and his name, Margarita’s uncle, Lef Papajani, to whom a son had just been born, quickly named him Robert. This was Robert Papajani, the future teacher of the Higher Agricultural Institute in Kamez. The “Kala” neighborhood of Elbasan has always been distinguished for culture and education. Kostaq’s aunt’s daughter, Sofia Xhufka, acted in the same way, who quickly named her first son, who had just been born, Robert. Even this Robert Xhufka, an inseparable childhood friend, became an educator but had the misfortune of dying at a young age, away from his family, from a very severe flu, and without anyone close to take care of him.

As in any family, also in Cipo’s family, all the actions performed by the first child of the house were shown as important events, which were narrated, embellished and repeated, every time someone came to visit. Margarita said that this little Robert, from the first day of his birth, was not able to suck his mother’s breast. Then one of the women prepared a piece of gauze for him and put a lollipop inside and brought it to his lips. He immediately began to suck it, but when they removed the gauze, they noticed to their surprise that the lokum had been completely absorbed. Maybe this was the first sign that would show that I would remain passionate and attached to sweets all my life.

Immediately, the two nurses, Kostaq’s mother, Agnija and Margarita’s mother, Angeliqija, came to help the woman in labor. It is remembered, apart from others that it is not necessary to dwell on, that the first word I managed to pronounce was “Piperka” (pepper), a typical Korça word that apparently made a great impression on me. But my health did not go well. Since I was little, I started suffering from tonsils. There was no disease or epidemic that appeared in Korça that did not affect me. Doctor Polena had learned this by heart, that every time the first flu appeared in Korça, my father would run to my house, sure that he would find me sick. Before I was even 5 years old, according to the doctor’s recommendation, we went as a family to Thessaloniki, Greece, to operate on my tonsils, because here in Albania, they were not sure if anyone would be able to operate on them.

After the operation, I had a noticeable improvement, but my appetite did not return, this is probably due to the family environment itself, who pampered me, always feeding me according to my wishes, only with sweets. My father even subscribed me to “Kafe Kursali”, where I had the right to enter and eat whatever I wanted, and my father paid the owner at the end of each month. At the same time, every time I woke up in the morning, I would find a “Nestle” chocolate under the pillow. I want to clarify that my first childhood memory is that of March 18, 1933. I remember that that morning, a woman (I don’t remember who it may have been) came and woke me up, and said; “let me show you the sister who gave birth to you”. He took me in his arms and took me to the other room, where my mother Margarita was laying on the bed and next to her was my sister Brunilda, a newborn. Then the memories begin to fade.

I attended the first year of elementary school exactly where the first Albanian school was opened, in 1908 in Korça and in Albania, while as a teacher; I had Virgjini Pepon, the daughter of one of the most intellectual families of Korça. A brother owned a printing press, “Pepo Printing Press”, where books and notebooks were printed and where the teacher often took us to see how it was done. Her other brother was Professor Petraq Pepo, professor of history at the Korça High School, who would later be interned in Colfiorito di Foligno, exactly where the Cipo family was also interned. Petraq Pepoja, would also participate as a member of the Government Delegation that participated in the Peace Conference in Paris in 1946.

During the three years of primary school I attended in Korça, I changed three schools, choosing each year the one closest to home. As I continued to have no appetite, every time I would eat lunch, a friend, Vangjeli, the son of the tailor Rrapi, would come to accompany me, who whenever the weather was good, would go out and mend the clothes that were brought to him customers, at the door of the so-called “shop”, which was located face to face with the house where we lived. This Rrapi always thanked Margarita for the meal his son ate with me. After the Liberation, we found out that Vangjeli, who was two or three years older than me, had become a partisan and was killed for the liberation of Kosovo.

My father, whenever he went for a walk in the afternoons or on Sunday mornings, he always took me with him and we went together to the hill of Shëndëllia and there we sat down to rest at a private cafe, where he ordered a coffee for himself, while for me a plum, or orange glyco. He had also bought me a small bamboo cane, a replica of the one he used to carry. Later, when Count Appony (Queen Geraldine’s brother) came to live in our house, I befriended him and played ball together in the backyard.

When Albania was invaded by the Italian fascists, I remember that after a few days they arrested my father. On one of those days, the teacher interrupts the lesson and informs us that the order came from the directorate that everyone should run home; put on the best clothes they had and go out near the Bank, to wait for the Italian troops that will come today. I set out with all my heart to carry out the teacher’s order and I ran home and since I didn’t find anyone there, I left in my school clothes to go where the teacher had ordered us. In front of the “Majestik” Cinema, two women had stopped talking, and when they saw me they said to each other; “his father was arrested and he goes to wait for the Italians”.

At the age of eight and a half, it felt like someone hit me on the head. I knew immediately that he was talking about me. I stood for a minute in silence, looking intently at those women, and then I slowly walked back home. The next day, the teacher asked the students if they had gone to meet the Italians. Then I stood up and said; “I didn’t go, they arrested my father.” It was the first objection, which would follow me all my life. This feeling would strengthen even more when, after a few months, I would go every day to take bread to my father in prison. The prison was outside the city and the river had to be crossed, since in that July-August period, it was almost dry.

Once the gendarmes, when the director was absent, took me inside the prison yard and there I saw all those prisoners, mature men, but also young ones, most of them mountaineers with northern cells. All of them stood for hours, in the inner courtyard of the prison, placed next to each other, where they did crafts, with colorful beads, which were passed from hand to hand. This scene left an indelible impression on me, for the rest of my life. A feeling of internal protest began to gather in my soul, which erupted at every opportunity.

During the period of internment, when they sat and talked after dinner, my father, Kostaq Cipoja, told about the vicissitudes that he had gone through in his life, since he was young, since he rose up in protests and dropped out of school, to force the introduction of the Albanian language in the Turkish school of Elbasan, the danger he had passed in Manastir, because of a patriotic poem, as well as all the protests against the fascists, since he was at the faculty in Rome, the association with Avni Rustem, the imprisonment of Zog, the opposition with the fascists who had occupied, imprisoned and exiled us, preparing me without his will, in a being who would always seek the right, the truth, always being in opposition, with any regime.

I gave the first sign in elementary school in Italy. I was in the fourth grade when, as the fascist teacher began to extol the splendid advances of the Italian troops in the Italo-Greek war, I rose from my seat and told her that; the Italian troops are advancing with their “shoulders”, not with their chests (i.e. in retreat). At that moment, she goes and complains to the carabinieri. They call him and reprimand him for the words spoken by me and the teacher that day, he expels me from school, telling me; “go and they will look for you at home”. At home I found my parents waiting for me. My father tells me that you have to be careful when you say your words, but on the other hand he smiled, maybe to himself, he felt proud of me.

After returning from exile, my father sent me to Elbasan, to his brother, and there I enrolled in the first grade of the “Normal” school. When he comes to see me, he takes the opportunity to take me by the hand and lead me to Thanas Fullani, the son of my mother’s aunt, who had just finished a vocational school in Athens, and had opened a carpentry workshop in the basement of the house his and says; “Take this guy and teach him a trade, so he doesn’t end up like me, who doesn’t know how to drive a nail into the wall.” During the year I stayed in Elbasan, every afternoon after I got out of school, I went and worked as a carpenter’s apprentice. This practice is very valuable in life.

There at the “Normal” of Elbasan, Prof. Petrac Pepoja. From this year of teaching at “Normalen” in Elbasan, I only remember the Italian professor, who made spelling mistakes and I, as a child, corrected him from the spot, putting him in difficulty, until we reached an agreement that I would not correct him. The teacher in the eyes of the students, but also the professor throughout the year, would not raise me in class. I also remember my friend from the bank, Bestar Dokja, who continued the traditions of children from Elbasan by raising balloons in the spring period, being the best of all. His balloon stayed in the air without falling all night and in the morning he was found still there, fluttering over the churchyard. I have forgotten all my friends from this class, I only remember that Dhimitër Shuterić’s sister was there, but with Bestar, although we see each other once every few years, we always keep our childhood friendship.

When we came to Tirana, as my father was on duty in Italy, at the “De Agostini” Novara Society, to enroll me in the “Naim Frashëri” gymnasium, my father’s uncle, Aleksandër Xhuvani, took care of me, who accompanied me to the school’s office , where they refused to enroll me in the second grade, as they said that the “Normal” school in Elbasan was considered to be of a lower level than the Gymnasium in Tirana, so what I had done in Elbasan was not for me, and here in Tirana, I had to enroll in first grade again. And so it was. Xhuvani paid the 5 francs for the registration and I was forced to repeat the first class, where I surprisingly noticed that it was the same texts and the same lessons that had taken place in the “Normal” of Elbasan. In that period, secondary schools, both “Normalja” in Elbasan and the gymnasium in Tirana, had eight classes each, since the first class started immediately after the end of primary school.

From the professors of that period, I remember the gymnastics teacher Adem Karapici who, in addition to teaching in the school gym, took us to the “Shallvare” sports field, where we played football, handball and basketball. I also remember Prof. Tatzatin, who taught us mathematics, Prof. Blakçorin, who taught us Italian, also Prof. Sitki Ciço, who was killed by Xhafer Deva’s men on February 4, 1944. Those were turbulent days. We high school students, from time to time, abandoned the lesson and attacked in demonstrations in the streets, although the principal of the school, Andon Dede, with that feeling of a parent full of responsibility for the lives of the students who were left in his care, tried to keep us in school, with the principle that the school should be apolitical.

After returning from exile, throughout my life, I read foreign and world literature, always in Italian. In the Albanian language, I only read the subjects and did not read any other Albanian writers. Many years later, after the 60s, at the suggestion of my friends, I read Dhimitër Shuteriq, Ismail Kadareë, Dritëro Agollin and Vath Koreshin. After the liberation, always having the feeling of rebellion in my soul, although my father was the Minister of Education and constantly a Member of the People’s Assembly, I always showed antipathy for governments of any color, as well as for the way of government, especially for the forms of subjugation to foreigners. This is probably also due to the fact that I constantly followed the programs of Radio London in the Italian language, being equipped with a political culture, which constantly kept my eyes open, to understand the crooked line where Albania wanted to enter.

I didn’t like the subjugation to Yugoslavia, which preyed on every commodity left over from the war period, which the merchants kept stockpiled in their warehouses, and not agreeing with the propaganda of the time, that all the socialist countries had to help each other, since every day only trucks were seen, which strangely came empty and left loaded for Yugoslavia. Based on these ideas, I always found a reason to protest in almost daily meetings of the youth organization, which were organized in the classroom after school hours, being targeted by the school organization.

To break this rebellion, after the second year of high school, together with a couple of other friends, we were removed from our class and transferred to the parallel class. But the same situation continues here. I created together with my friends, what today, after fifty years, is considered as something normal, a “Government”, being the prime minister himself, as well as a chief of staff, with several ranks of “major officers”. Except for a few people associated with the youth organization, everyone else had turned in favor of our “rebel” group, having at the same time the sympathy and moral support of the teaching body.

From the first year of high school, I remember a painful event. In our class there was also Aminta Papahristo, the son of Prof. Sotir Papahristos, a colleague of Kostaq Cipos, from the French Lyceum of Korça, with whom we had a common friendship for the age. During the 1st year holidays, our school volunteered for the construction of the Durrës-Elbasan Railway and we were placed at Km. 5, at the exit of Durrës, approximately where Iliria Beach is located today. There I fell ill with Malaria and was admitted to the Railway Hospital. There he hears about it and comes and drags me, causing the opposition of the “friends of the youth”, because according to them, I had abandoned the war front. Aminta Papakristo also fell ill there, which after suffering for several months died, causing deep pain, both for us who had him as a classmate, and for all the acquaintances of Prof.’s family. Papahristos. I attended the funeral, carrying the coffin with my friends.

Our group of students, in addition to openly expressing opinions against the government, had among them the best of the class in lessons, most of them, in addition to the Albanian language, also knew a foreign language, especially Italian or French, entering into fiery literary controversies and philosophical, either among friends or often even with our professors, debating about writers and poets of the Western world and, creating pride and envy among the ignorant in the class, “communist youth friends”.

At that time in the gymnasium, the cream of the Albanian intellectual educators taught, such as; Skender Luarasi, Fejzi Dika, Nonda Bulka, Prof. Karajani, Prof. Babamusta, Ollga Luarasi (Migjeni’s sister), Zoja Ndoja and her husband Injac Ndoja, Gabriel Meksi, Fadil Rrepishti, who had translated the physics text from Italian to Albanian. But we had special sympathy for Prof. Ahmet Gashin from Kosovo, who came to Albania before 1912 and settled in Elbasan, where he started teaching in the city school, also directing the musical band “Afërdita”. He was already at a very broken age; he had been spiritually killed, since the “communist power”, only at the request of his Yugoslav “comrades”, had shot his son (Luan Gashi), who was trying for the independence of Kosovo. Although in retirement, he became for us his students, a true friend. He often invited us to his home to show us around the library and play a game of chess together.

By the end of the third year, the youth organization set out to break this sense of protest that was not fading, as well as in cooperation with the director of the gymnasium, the pseudo-scientist Stefan Prifti, who himself devised, organized and implemented a dirty plan . Finding a cause without any importance, and in order to cut off the head of this rebel organization, they expelled me from school for the last three months of the third school year. Quite shocked, I go to meet my father and find him in the State Bank, paying the house rent and I told him that; I was expelled from school for three months. My father, Kostaq Cipoja, who, throughout his school life, had gone through so many such vicissitudes, instead of shouting at me, cursing me, or any other kind of action, calmly told me; “These three months, study and at the end of the year, go and take the exams, and now let’s go eat lunch at home, because we’re late.”

But it would not end there. When they saw that they did not overcome this situation, which was getting stronger every day, with the beginning of the fourth year, which was also the year of graduation, seeing that these labeled “reactionaries” were very good students in lessons, with culture, with foreign languages and would certainly be the main contenders to receive a scholarship, for studies abroad, organize a mass exclusion, adding to this list also students, with supposedly politically persecuted parents. When I myself am asked about this period, which happened half a century ago, as far as I can remember, I can say that; “in the first month of the graduation year, in September 1948, at the general meeting of school students, measures were taken for a massive beating of rebellious students. Officials from the Party Committee, the Ministry of Education, and the Youth Committee were lined up in the presidium, while from the Prime Minister’s Office, the Deputy Prime Minister “comrade” Spiro Pano assisted.

With a ceremony, they make the official announcement for the permanent exclusion from all the schools of Albania, of the students; Robert Cipo, Rustem Çelo, Alfred Benussi, Gani Karapici, Reshat Karapici, Kostaq Xoxa, Bamir Çano, Thoma Xhitomi e, Thoma Marto. The Youth Organization, according to the fascist methods alienated by Ducja but also by Tito in Yugoslavia, (perhaps this was also the case in Stalin’s Russia, since all dictatorships have a common denominator), had planned, organized and divided the tasks, for the organization of a collective beating, by their schoolmates themselves.

Also, for this “magical” ceremony, the “honorable” Principal, Stefan Prifti, had also given his approval, since the funeral would be organized and implemented in the school where he was the principal and where the parents had handed over their children, for him educated, he himself, as much as possible, stayed locked in the Director, rubbing his hands, and forgetting that he was legally responsible for this charade that was happening in a state institution, where he had the main responsibility towards the parents, for the beating that was done to their children.

Can this humble man be compared with the former director of this school, Prof. Andon Deda, who when in 1944, two Kosovars sent by the German Gestapo, came to the school to arrest two students, sympathizers of the Partisan Movement, drove them out and faced the threats of the Gestapo with his body, telling them that; until they have come to school, I am their parent and I will not allow you to touch them, not a hair. While this director of the Party, instead of opposing an inhuman act and publicly resigning, allowed a Deputy Prime Minister to commit a vile anti-school act in the school environment. So this person (who cannot be called human), ate the shame with bread and those who participated and stood out in this beating, with the suggestion of the above delegates, took care and filled out the documents himself with the personal recommendation that to win scholarships to continue their studies abroad. Memorie.al

The next issue follows