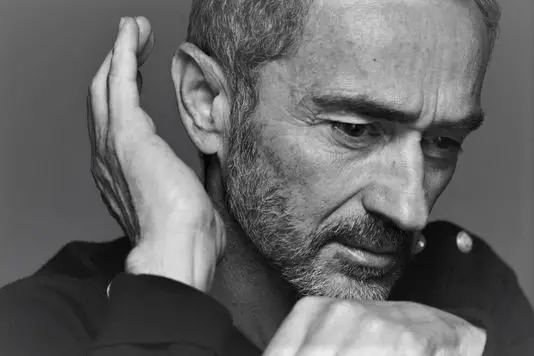

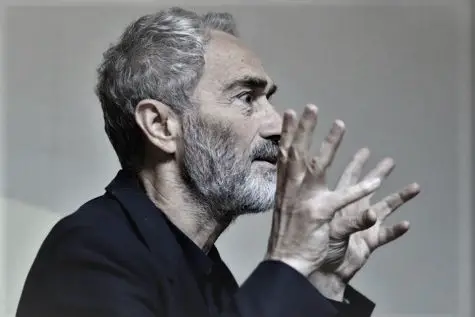

Memorie.al / On May 14, 2014, the world-renowned Albanian choreographer Angjelin Preljocaj was invited to the television channel “Albanian Screen” on the show Prizëm, hosted by journalist Aleksandër Furxhi. In this interview, Preljocaj – whom the great Albanian writer Ismail Kadare has called “The Cousin of Angels” – spoke about his return to Albania after 20 years, his family’s escape, and his first encounter with ballet at a young age, and his career as a world-class dancer and choreographer.

Mr. Preljocaj, let’s try to remember how your childhood began – your family’s departure from Albania and their origins…?

My father is originally from Vermosh, in the north of Shkodra. He lived there with his family for several years. One day, together with his father and younger brother, they decided to leave Albania and cross the border as emigrants, partly to reunite with his wife who was in Ulcinj (Ulqin).

In what year?

It’s a bit blurry since I wasn’t born yet, but I think it was around 1955… then he found my mother and they got married there. They stayed briefly in Berane (then Ivangrad) and were later sheltered in a refugee camp in Gerovo, in the former Yugoslavia. They were waiting to immigrate to America; that was the initial plan. My parents told me I was conceived in the Gerovo camp. Then they continued their journey to France, where they waited for their visa to depart for America.

And you were born in France?

Yes. As soon as they arrived in France, I was born. It had taken them quite some time to reach France.

So you were born in 1957…?

Yes, 1957. While they were waiting for their American visa. They couldn’t get the visa for about a year or a year and a half, and by the time they did, my parents had started to stabilize. So when the visa finally arrived, they said: “Okay, let’s forget about America; let’s stay in France because we have started working and have a small house.” That’s how they decided to stay.

At home, I believe your parents spoke Albanian. But you, as you grew up, how did you communicate with them?

Exactly. Since my father and mother arrived in France and I was born immediately, at a time when they didn’t speak French and had no “key” to French culture or tradition, my entire childhood was in Albanian and within Albanian tradition. I think that often, newly arrived immigrants feel the need to preserve their identity and are forced to be “more Albanian than the Albanians themselves.” I have the impression that I was raised more within the Albanian tradition than those in Tirana.

It was something very, very strict and traditional. For this reason, I always felt I had a dual culture: at home, it was still Albania, while at school; it was the school of the Enlightenment, the French Republic, and the discovery of an entirely different culture. I felt that on one side was tradition – something deep and somewhat mysterious – and on the other, the culture of the Enlightenment philosophers and all of French culture. A duality.

How was your first contact with ballet? I read in the New York Times that you were about 11 years old when you saw a photo of Nureyev and something sparked in your mind… Is that true?

Yes. It’s funny that my love for ballet was born from a still image. It’s paradoxical because dance is movement, yet my taste for ballet was sparked by a static image. It was a photo of Rudolf Nureyev in a book I had borrowed. There was such a light and beauty in his face that it mesmerized me. The caption was interesting; it said: “Rudolf Nureyev transfigured by dance.” Meaning transformed, metamorphosed by dance. I thought to myself: “This is unbelievable.” I wondered what kind of art could transform someone and make them so beautiful – beautiful from within, not just on the outside. I returned the book to the girl who had lent it to me – she was a young ballerina – and I asked her where she did ballet. She guided me, and that’s how I went to my first dance class.

I’ve read that at the time, you were enrolled in a judo course, but you spent the money to go to ballet instead. Is that true?

Yes, it’s true. For my first ballet class, I went wearing my white judo kimono pants and a t-shirt. I didn’t tell my parents. I often went to dance but told them I was going to judo. It was a secret because my parents did not want me to get involved in ballet.

When they found out you were attending ballet classes, how did they react?

It’s interesting. My mother didn’t oppose it much at first because she simply didn’t know what ballet was, especially classical ballet. My mother had been a farmer, a shepherdess tending sheep; she came from a social class where classical ballet was totally unknown. So there was neither a positive nor a negative reaction, which wasn’t bad.

Since she was working in a factory in France, she asked her colleagues: “What do you think? My son is going to ballet; he wants to be a dancer.” Those around her told her it was a strange thing that it was for “feminized men,” and all the clichés of the time. My mother became a little afraid for me because she dreamed of me becoming a doctor or a lawyer – something like that. She was worried.

At 17, you left for the USA to pursue ballet. Why the USA?

I had started studying classical ballet, then modern ballet, and I realized that choreographic innovations were appearing mainly in New York. I wanted to go there to discover the new trends. I met and worked with Merce Cunningham, from whom I took lessons and learned a great deal regarding choreographic composition.

Is it accurate to say that America formed you as a dancer? Or France as well?

France as well, but also the USA. At that time, the United States was the center of gravity for creativity, but a lot was happening in France too, allowing young dancers to establish themselves.

Ballet Preljocaj has about 26 dancers and produces more than 100 shows a year. How is that possible?

It is a lot of work, but I don’t want to complain because it is a passion for the company. At the same time, I don’t only produce shows with 26 dancers. For example, Royaume Uni is for 4 dancers; some shows have 12, while others involve the whole company, like Snow White, which is a large ballet. Sometimes, part of the troupe is in London while the other is in Madrid; on the same evening, we perform two different ballets with the same company.

With the Tirana Ballet Theatre, perhaps it is just the beginning. Do you have any ideas or projects to develop this collaboration?

Not only is it possible, but we have already started. Under the auspices of the Ministry of Culture, we signed an agreement between the Tirana Opera and Ballet and Ballet Preljocaj. It’s a three-year agreement – an opportunity for deep collaboration, not just consuming ballet but exchanging it. This means pedagogical education, dancer training, and sharing ballets with the Tirana Opera, as well as creating new works together.

It is a very interesting cooperation. For instance, we could combine 5 dancers from Preljocaj and 5 from the Tirana Opera to perform together. It would be beautiful – it could be 10 and 10. What is interesting is the merging of energies; to see how we can create a dynamic, perhaps even explosive, mixture.

When you first came to Tirana, you danced on stage yourself; now you are here as a choreographer. How many years has it been since you stopped dancing?

It’s strange that you ask, because it’s only been three years since I last performed a solo, which lasted about an hour and fifteen minutes.

In your family, have your children followed their father’s example? Do they share your sensitivity toward ballet?

I have two daughters who love ballet, but they are following the example of their mother, who is a filmmaker. I think they are enriched by both arts: the choreographic art and the cinematographic art. / Memorie.al

![“Count Durazzo and Mozart discussed this piece, as a few years prior he had attempted to stage it in the Theaters of Vienna; he even [discussed it] with Rousseau…” / The unknown history of the famous Durazzo family.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/collagemozart_Durazzo-2-350x250.jpg)