By Prof. Ramdan Sokoli

Part One

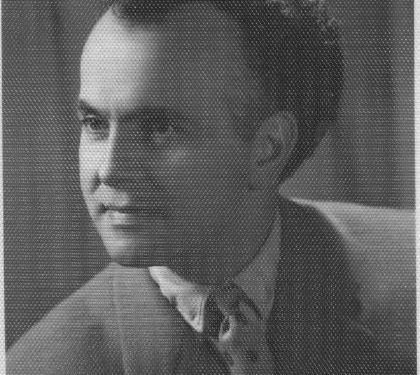

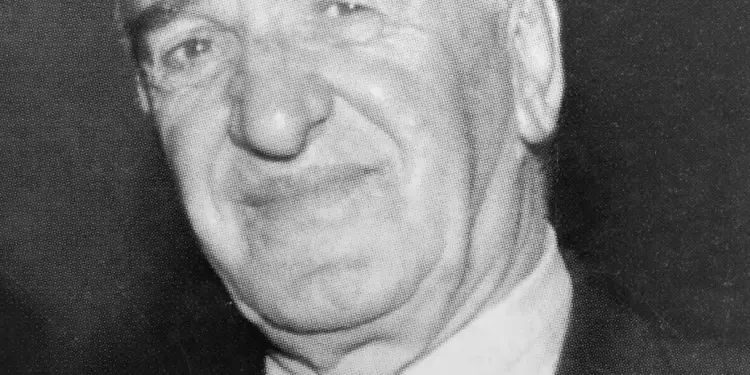

Reflections of the renowned musicologist and former political prisoner

Preface to the Book – ‘In the Footsteps of a Diary’ – Shkodra in the Early Years of Communism

By Ahmet Bushati, former political prisoner

“O God, do You not see?

The traitors have left us without a homeland,

Yet You sit and hunt with lightning,

While the oaks in the mountains stand in vain.”

Padër Gjergj Fishta

Memorie.al — Here is a harrowing book about the communist genocide in the region of Shkodra. For half a century, this land was brutally oppressed, humiliated, and degraded—even the future of the nation was pushed to the brink of the abyss. Shkodra, with its national traditions and especially its freedom-loving youth, thirsty for light, justice, and dignity, dared to resist the red yoke. Many patriots who refused to submit to the savage regime were crushed, even annihilated. But let us recount events as they unfolded.

Undoubtedly, the patriotic struggle against the Nazi-fascist occupiers marks one of the most heroic chapters in our history. That chapter, written in blood and countless sacrifices, stands as the greatest testament to the patriotism of our freedom-loving people. As is known, the Albanian Communist Party was founded during that time, organized by Serbian communists. Consequently, it harbored Pan-Slavic tendencies. The teachings and historical experience of our ancestors were disregarded. Even during the era of “fraternal ties” with the Yugoslavs, national issues were ignored.

The partition of Albanian lands was accepted. Albanian communists never raised their voices against the massacre of Kosovars in Tivar or the atrocities committed by the Greeks against the Cham population. Yet, not all communists were devoid of virtue. Though deluded by deceptive utopias, many among them sacrificed themselves and stood firm in self-denial. During the war years, they behaved nobly, but tragically, many were broken by the yoke of totalitarian dictatorship. However, there were also fanatical communists, narrow-minded and rigid, who fought fiercely for power and revenge. Later, they revealed their true nature through their actions.

First, they settled scores with their declared opponents—the Zogists and Ballists. Then, they purged educators, especially the more experienced military officers, deeming them “unfit.” The right to free expression was violated, even the freedom of thought. The “Democratic Front,” a tool of the regime, had nothing in common with true democracy. The strategy of dictatorship, contrary to democratic principles, was violence, terror—the very engine of its machinery.

Those deceived by the tricks and promises of freedom, brotherhood, equality, and other idealistic principles; those who believed the utopian slogans about building an ideal social order (without realizing that “utopia” means “nowhere”)—later, when they began to think for themselves and refused to act like marionettes controlled by others, their dreams were shattered. When, instead of prosperity and lofty ideals, they saw the destructive currents pushing the homeland toward the abyss, they finally understood: they were burning in a fire they themselves had ignited.

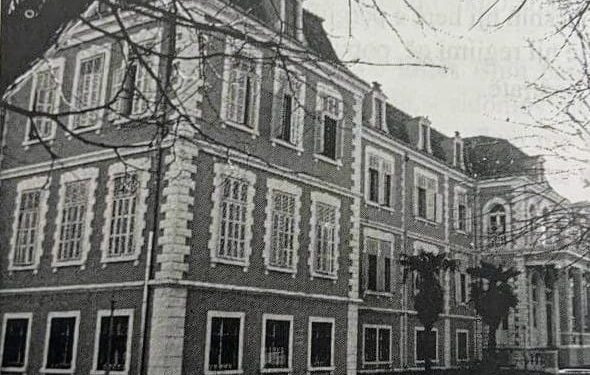

All merchants and artisans were labeled, their property confiscated; the state devoured their labor and sweat. It was as if they were skinned alive. Private property was abolished, and everything was nationalized. With the destruction of the old city bazaar and its 2,500 once-thriving shops, Shkodra was engulfed in silence and misery. Everything was clouded and poisoned by the ideological “virus.” Everything was shattered and transformed.

The so-called “people’s power,” under the infamous banner of “class struggle,” sowed discord and opened the abyss of division among fellow patriots, replacing brotherhood with hatred. To suppress the free-spirited movement of local youth, convicts from the southern regions of Albania were brought to Shkodra’s gymnasium. They deepened regional divisions between Gegs and Tosks.

Later, they left behind a notorious legacy, especially as henchmen of the State Security. The infamous “class struggle” exploited another tool of division: wall posters. Through this Chinese invention, anyone targeted was publicly shamed and attacked with offensive labels (bourgeois, agent, traitor, etc.).

With the “molding of the New Man”—a man without conscience or character—the noble traditions of faith and honor, inherited from our ancestors, were torn apart. The most distinguished, knowledgeable, and upright individuals were persecuted. The freedom-loving city of Shkodra was labeled “reactionary” by the regime. But the freedom-loving people of this land, with their heightened national consciousness, historical experience, and cultural heritage, resisted the red yoke. Groups of young men printed and distributed leaflets against the regime, while uprisings erupted in the mountains—crushed in blood by the “People’s Defense” forces, as the State Security branch was then called. Military trials began, the so-called “people’s courts.”

The tragic farce, laden with sadism, condemned innocent “culprits” to death. At times, the cries of the condemned echoed at dawn, followed by gunshots into the victims’ bodies, which were then dumped into mass graves. In early 1945, one such execution took place in the city center, near the Municipality, in front of a jeering crowd. In September 1946, a large-scale popular uprising erupted in Postribë.

Tragically, this uprising also failed and was drowned in blood. It served as a pretext for a new wave of state terror, particularly against local elites, intellectuals, and clergy. A red state terror that reached extreme brutality, surpassing even Nazi-fascist terror. The military trials—those tragic farces like insatiable beasts—demanded human sacrifices. And the Sigurimi, aiding these trials, committed atrocities against countless innocent victims.

In 1946, within the city alone, there were 13 overcrowded prisons. “The house of prisons,” as Shkodra was then called. Beyond political prisoners, many were interned, and countless families were expelled from the city and scattered across agricultural cooperatives. Many never returned. They remained there for years, where they multiplied, where their descendants were born and raised. O God, what horror and savagery!

After the judicial sentencing of the accused, when the convoy of the condemned—bound and chained—passed through the streets on their way to the prison for “enemies of the people,” they were met with the howls and taunts of the Sigurimi thugs, who hurled every manner of vulgar insult. Woe to the patriots who languished in prison, in the red inferno of the communists! Woe to the prisoners who fell into the clutches of those cruel investigators, beastly and demonic, who roared like enraged gorillas.

Those who endured it on their backs know how hard it is to describe in detail the unimaginable suffering of interrogation—hours, days, weeks, months, even years. Naked, shackled in dark cells, threatened and tormented, beaten and tortured without mercy. The executioners’ assistants, to drown out the screams of the tortured, sang and danced in Greek: “Piosi more piosi, i dhe to Jorgo, to Jorgaqo.” This was the height of cynicism. Beyond the sadistic mockery, what else could one expect from such hate-filled creatures?

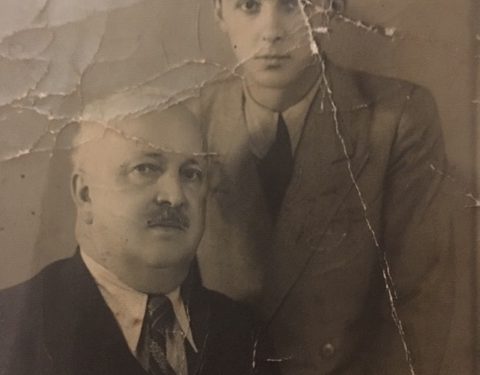

Under such inhuman conditions, it was nearly impossible to remain unbroken. Many of the accused were forced to confess to fabricated crimes. But conversely, there were also true heroes who sacrificed everything, even their lives, facing death with open eyes. Among the prisoners, the young Ahmet Bushati stood out for his exemplary and unyielding resistance. He endured endless tortures with unwavering resolve; he bore hunger that reduced him to a skeleton, covered in festering wounds.

Not only did he refuse to betray his comrades, but he also never signed a single “confession.” Through his steadfastness, this young man (with only women left at home) honored not only himself and his family but also the community that had shaped his heroic character. The people say: “If you praise someone to their face, you insult them.” So forgive me, dear Ahmet, but for the sake of truth, I must praise you publicly here in the preface to your book.

In 1948, the “eternal friendship” between Albania and Yugoslavia collapsed. It was declared that the so-called “internationalist understanding” with Tito’s brothers had never been sincere or mutual but a one-sided deception by the chauvinist Serbs. Criticisms arose over past subservience. Temporarily, there was a shift: the torture of prisoners during interrogations was halted—blamed on “Comrade Koçi Xoxe,” the former Minister of Internal Affairs, who was condemned as a traitor and liquidated along with his associates. This phenomenon would repeat itself later with other communists, proving the saying: “The revolution is a beast that devours its own young!” After the break with Tito, nothing fundamentally changed—only superficial adjustments.

The Albanian communists continued their idyll with the Soviet Russians. Meanwhile, the Albanian Communist Party changed its name to the “Party of Labor,” though it remained the same Stalinist entity. As the people say: “The wolf changes only its fur, not its nature.” After the upheavals in the socialist camp, they tied themselves “eternally” to the Chinese. When all idols crumbled, after being betrayed for the third time by their “internationalist brothers,” Enver Hoxha continued to proclaim himself the defender of Marxist-Leninist purity—even as this ideology faded worldwide. The demagoguery and adventurist policies of this madman led to Albania’s isolation in a bunkerized shell.

Prison, as an environment of suffering, is rightly called “the scales of character.” There, the author spent his youth. There, he was shaped into manhood and tempered. There, he witnessed many painful events alongside his fellow sufferers. There, he met a gallery of characters and delved into their spiritual fluctuations between hope and despair—especially those driven to madness, suicide, or the brink of death. There, he grew close to the cream of political prisoners.

Beyond intellectuals and creative artists, there were also bearers of our national heritage. Reflecting that grim reality, the author, as a sharp observer, has truthfully depicted dramatic and chilling scenes, as well as captivating episodes with biting humor, laughter, and jokes that momentarily eased heavy hearts. Thus, even in darkness, Shkodran optimism shone through.

After the interrogation period and imprisonment as an “enemy of the people,” the author endured the horrors of forced labor camps. Generally, communist camps—like those in Beden, Maliq, etc.—competed in mistreatment, suffering, exhaustion, and brutal labor under impossible quotas. Words cannot capture the tragedy of those martyrs—starved, parched, and worked to death. There, many lives were extinguished. There, their corpses were buried without markers or gravestones. (The “people’s state” never returned the bodies to their families.)

Ahmet Bushati’s book unfolds before the reader many grim and horrifying images of a homeland crushed under the red totalitarian yoke—a land left isolated, cursed, and abandoned. That tragic era for our nation was marked by political, economic, social, and cultural calamities—a time of material and spiritual ruin. Proportionally, no other country in the world imprisoned, tortured, or killed more dissidents per capita than this subjugated, shaken, oppressed, and humiliated people.

This book is written in the dialect of Shkodra, with accentuated local flavors that highlight its regional character. Even in this regard, Shkodra—with its rich artistic and cultural traditions—paid tribute to that violent regime, which, under the guise of “linguistic unification,” marginalized the Geg dialect and scorned the wealth of its vocabulary—leaving black stains on our national cultural heritage.

After release from prison or labor camps, former political prisoners faced continued suspicion, surveillance, and persecution. Thus, those prisons expanded into a larger, bunkerized prison behind an iron curtain. Such was the miserable state of socialist Albania. Wise men learn from suffering. Hence, evil must not be forgotten.

This deceived and betrayed people, who suffered under the red yoke—which dishonored, imprisoned, and brutally tortured them—cannot forget the terror of totalitarian dictatorship. The perpetrators of misery, the causes of so many mothers’ and sisters’ tears, the heartbroken widows and orphaned children, the architects of national ruin and genocide—must face deserved punishment. Nothing absolves the bloodstained hands of those who compiled the “blacklists of death” for patriots.

Surely, democracy must rectify this injustice. In democratic France, the guillotine deals with traitors and criminals; in the USA, the electric chair. Yet here, they roam free. Those who, with Enver’s iron broom, annihilated the cream of patriotic, freedom-loving men.

How can this people endure the former interrogators, prosecutors, judges, and executioners—those hated monsters who, for nearly half a century, drank their blood like leeches, inflicting every imaginable torture?! When you see these beasts, who spared no cruelty, walking freely through the streets, careless and unrepentant—it’s a wonder none of their many victims has sought revenge. They feel no remorse, no shame for their atrocities! On the contrary! Perhaps they mistake the victims’ patience for weakness. Walk and do not rage! Walk and do not despair! For them, the curse of the national poet Gjergj Fishta is fitting:

“Oh! May they be cursed by God,

May his wife be left a widow,

May his son be despised,

Clothed in foreign rags,

May he beg at every door,

And find no one to show him mercy.”

I hope this book serves as a warning—even a cry—against forgetting the terror of communist hell. It will especially serve future generations, teaching them the mistakes, deceptions, and horrors that brought national ruin. At the same time, it will acquaint them with the resilience and sacrifices of true patriots. From this perspective, Ahmet Bushati’s diary holds immense value. I wholeheartedly hope these painful experiences, these struggles and sacrifices, will not be in vain./Memorie.al