By Shkëlqim ABAZI

Part eight

SPAÇI

– The Grave of the Living –

Tirana, 2018

(My own and others’ memoirs)

Memorie.al / Now in my old age, I feel obliged to confess my truth, just as I lived it. To speak of the modest men, who never boasted of their deeds, and of the others whom the regime silenced and buried in unnamed graves? In no case do I take upon myself to usurp the monopoly of truth or to claim laurels for an event where I was only accidentally present, although I desperately tried to help my friends, who tactfully and kindly avoided me: “Brother, open your eyes… don’t get involved… you have only two months and a little left!” A worry that clung to me like an amulet from the morning of May 21, 22, and 23, 1974, and even followed me in the months that followed, until I was released. Nevertheless, everything I saw and heard during those three days, I would not want to take to my grave.

Continuation from the previous issue

I understood, he wanted it for a signal. “Even bad things are useful sometimes!”

“It’s true!” – Jemini confirmed.

“What did you say?”

“The fire from the cigarette is a good signal!” – He repeated.

“Even bad things are useful sometimes,” I repeated and clenched my teeth so as not to speak out loud. Suddenly, I remembered the old women in the neighborhood who used to advise me when they saw me with a book in my hand:

“Keep your mind sharp, my son, the grain of wheat is precious, and it flies away quickly, and never returns!” The ember glowed like a beast’s eye.

As if from the bottom of a well, a knock was heard, and two sparks flashed.

“Fireflies in the dark,” I was inspired to give a poetic caption to the sad moment. Meanwhile, the sparks grew to the size of lights, as we waved our cigarettes in the air.

“Get off the rails, you idiot!” – My colleague pushed me behind the reinforcement, while the wagon slammed into the roadblock.

“Did you break them?” – A shadow from the darkness snapped at me.

“Life must have bored you, my friend!” – The other one said.

“We are in trouble, the wagon came off the turntable, and we can’t find the lamps,” my colleague explained.

“Jemin, is that you? But what got into this simpleton to block our way?!”

“Thank goodness the brakes worked, or you would have flown to the woods (idiom for ‘gone bad/away’), my friend!” – And he shook a long pole.

“It’s his first time, he is new!” – My colleague justified me.

“Ah-ah, keep your eyes open, man, or you’ll leave your bones here!”

We got under the wagon that was stuck in the ditch, but we couldn’t move it.

“Let’s unload it, because where it’s stuck, we won’t get it out all day!”

We threw the stones onto the crossties and lifted it up, put it back on the rails, loaded it again, and set off one after the other. Now the track was uphill, the wheels barely moved forward, so we had to put our shoulders into it.

Eventually, we came out into the light, after about a hundred meters, we stopped by a wooden stall, covered with black sheet metal, which I heard them call; “The slope’s trimozha (a technical term for a funnel or chute).”

Strange names, as in the Siberian Gulags: “baramina” (crowbar), “pjatina” (turntable), “orti” (a type of gallery), “trimozha”!

“Save us, O God!” – I expressed unintentionally.

“Forget the prayers and pull the safety pin!” – My colleague brought me back to reality.

I released a clamp under the bucket, which rotated sideways, and the stones tumbled down, rubbing against the sheet metal of the trimozha, where they loaded the trucks with the material we were extracting.

I snatched the first wagon from the mountain, which, in the course of years, would be followed by thousands of others, filled with copper and pyrite…! From that moment on, I would be a daily contributor to the construction of socialism.

Thus, I would bring to life the Party’s slogan: “One gram of mineral, one bullet for the enemy,” which the executioners of Spaç implemented one hundred percent.

The Cupil and the Donkey’s Tail

“Hurry up, brother, we have six more wagons waiting, otherwise we’ll sleep in the cells!” – Jemini shook the dreams out of me and went towards the stack where he selected some logs; we loaded them and returned to the hole we came out of.

Now we had to rush to make up for the lost time, because by that hour, we should have extracted three wagons.

At the front, Arshini was busy with an adze, carving small pieces of wood, the size of a palm.

“He’s wasting time!” I thought, but later I learned that these small wooden pieces, called “kleçka” or “cupila,” were used to secure the support pillars.

With the “kleçka” or “cupila,” the pillars were tied, inserting them into special brackets prepared specifically at the top of the log, where the vertical met the horizontal, which I heard them call the “kapela” (hat/cap).

Again, strange names, like: “Cupila”! “Cingla” (rock/stone fragments)! “Kut” (hole/side passage)! “Kut, e cingla”! “Kapela”! The caps and our heads! Right above our heads, the mountain would pour down, and we had to hold it all up! Hell of a job, what iron heads we must have had, to hold up the mountain-cap?!

So, they fixed the cupila at the horizontal branching and rammed them with the butt of the axe. After placing the kapela on top, they spread a series of logs or halves, depending on the location, and reinforced them against the rock with wedges, to create a solid mass.

The policemen and brigadiers checked the cupila first when they stepped onto the front. If you didn’t reinforce them enough, they’d make you start over, and if you ignored them, you faced consequences, up to a month in isolation.

My friend, Tomor Allajbeu, would often be punished for the cupila. In fact, his original theory: “The cupil resembles the donkey’s tail; as necessary for scaring flies, so unnecessary for hiding the dung,” had become popular in Spaç.

One day Preng Rrapi, with brigadier Ndua and the convict Rroku, inspected the face of the front where Tomor was working. When they noticed the cupila moving in their sockets, they ordered him:

“You must start over!”

“Why should I start over?” – My friend replied.

“Because they move, man!” – The policeman shook the piece of wood.

“So what if they move?!” – Tomor replied.

“Right after the blast, they’ll fall to the ground!” – The free brigadier intervened.

“Go back to work, unless you want to spend the night in the cell, you old man!” – The policeman smoked the logs with the flame of his lamp. Tomor left, supposedly to repair them, but he waited until the escort left.

The next day they returned to the workplace and went directly to the cupila that “branded” Tomor: “Why didn’t you tighten the cupila, old man?” – They snapped, seeing that they were barely moving, just like the day before.

“Who said I haven’t tightened them?”

“Why should someone tell me when I see them myself?” – Although he shook them, he couldn’t pull them out; – “Look how they move, man?”

“I see!” – Tomor replied calmly.

“Tomorrow, you’ll find them on the ground!” – The policeman pushed him.

“If they didn’t fall today, why will they fall tomorrow?”

“They move, man!” – Prenga snapped.

“And then what?!”

“They’ll be shattered, I swear!”

“Even the donkey’s tail wags and shakes, but it doesn’t break off! Have you found any tails on the roads, sir?” – Tomor shot back, but he paid for this joke with a month in the cell.

We extracted the second, third, fourth wagon, up to the last one, which I almost commanded myself.

My body ached, especially my calves. But the work didn’t end there; the logs that Arshini prepared while we were filling and pushing the wagons had to be lifted and reinforced to form a safe shelter. We carved small pits especially at the base of the rock, buried the pillars and fixed them opposite each other, at a height where the brackets would align when we put the “kapela” and would fit perfectly, as if cast in a mold.

The craftsmen combined the fork holes so well that they didn’t need to use force; the cupil would fit with just a hand. When we finished with the logs, we started filling from the center of the “kapela,” avoiding the side where the cupil was, then behind the pillars.

Since the half-logs took up space and didn’t move, it was more convenient to split them outside, so we could have them ready when needed, but this process required skill, so unintentionally, we also became woodcutters.

While erecting the reinforcement, Arshini fixed the drill onto the metallic axle and the holes. Now the compressed air blew away the thick smoke. The mask hindered my breathing, my eyes burned, but the work had to be prioritized, because the dynamite setters were coming to fill the holes with dynamite for the next shift’s blast.

Whoever didn’t complete the cycle ended up tied to the pillars, while repeat offenders were laid out on the “zdrukth” (wooden bed/rack) in the operative’s room and then sentenced; seven, up to a month, in the cell. At the end of the shift, I felt exhausted…!

A Little History on Equipment and Food, Astronauts, Out of Necessity!

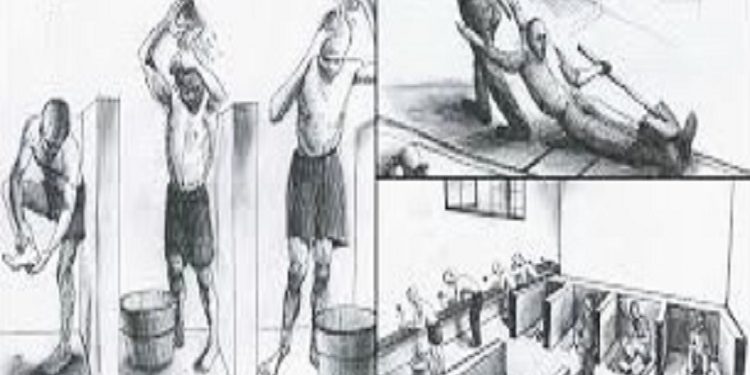

The clothing was based on tropical and subtropical practices. In Spaç, they dressed us thicker to exploit us longer. Among the prisons, an imported model was applied, initially from the Gulags of Russia, later from communist China and Cuba, countries that supported the extreme Marxist-Leninist policy and exported the banana leaf, typical of the tropical and subtropical climate, which consisted of reduced norms; especially light clothing and meager food.

The norm included two canvas suits per year, a brown fur coat every three years, stuffed with cotton waste (in China they said they stuffed it with rice husks, in Cuba, with sugarcane residue), two pairs of rough poplin drawers and shirts that grated the skin like sandpaper, two pairs of patches, made of the same fabric, a pair of rubber sandals, made from used tire remnants, and was completed with a hand-stitched cap, made from the patch fabric, which was not foreseen in the norm, but they had allowed it, in respect of the ala-Lenin, ala-Mao cap or the ala-Fidel sombrero.

With these feathers, we should have died, but the human adapts to conditions. Dressed like this, we resembled the Mongolian cavalry, who are remembered as lightly armed formations, but very maneuverable and highly effective in surprise attacks, as well as very agile in retreat; we too, battered by the winter frost, were always in a state of alarm and nightmare.

In Spaç, besides the above norm, they added an over-norm, which was useful inside the galleries but unfavorable outside the holes.

They provided us with a fur coat suit; naturally, it wasn’t a matter of precious animal fur, but canvas trousers and jacket, stuffed with cotton and stitched with parallel quilting. As I mentioned above, for stuffing they used waste from the cotton ginning factory in Rrogozhinë or Fier, often with seeds, which attracted mice to tunnel inside the clothing. Whoever kept this awful clothing in sacks was likely to find colonies of mice.

When I first heard it, I took it as hyperbole; but setting aside the sarcasm, I refer to my case: for a whole month, the trousers of this awful suit made my calves bleed. Initially, I thought it was a dermatological problem, resulting from the pyrite water, or mine fungus and bacilli. Something sharp bothered me so much that one day I decided to cut them open, and what did I find, you ask? No less, no more, a handful of burrs, which made my fingers bleed.

While in the garbage collection area, on the slope below the latrine, one summer my eye caught a cotton plant with flowers. Strange, the seed had preserved its vitality and had sprouted right under the edge! This unexpected, unimaginable event almost cost my friend, Hajdar Qerreti, his head. Confused by the broad-leafed plant and the white flower, he thought he was in his village, where the plant reached record yields. Bewildered by the miracle, he hung himself down the slope.

“Where are you going, Hajdar?” – I shook him and swayed him to bring him back to his senses. He stopped, but when I shook him a second time, he came to.

“Where are we, for heaven’s sake?” – The man from Myzeqe was shocked from head to toe.

“In Spaç, my friend!”

“What is cotton looking for here?!”

“They must have brought it for re-education, or for a Party internship!”

“May the devils eat them; they want to spread the red seed everywhere!”

“Cotton is white, Hajdar!” – I interrupted him, laughing.

“Forgive me, but they put it offside; it’s not in its homeland!” – And melancholy overtook him.

They also gave us a canvas jacket with a layer of bitumen, which they called a rain gear. Later they added a pair of trousers, slightly increasing the quality, but still, the fabric was rubberized canvas.

The uniform was completed with two pairs of gloves and two pairs of uncombed wool socks, products of the “Stalin” Textile Combine, as well as two pairs of rubber boots from N.I.SH. “Goma” Durrës, and was finished with a cardboard cap, an imitation sole, without any quality. This bulky collection of clothes turned the thin men into heavyset figures, so much so that they could barely move their feet.

Submerged in the enormous carcasses, they resembled nomadic riders, with horses and bronze armor, with long spears and large spiked clubs, with gigantic shields and heavy swords, so much so that three people were needed to help them mount and dismount their horses, but in a clash, you found few, or no, unprotected points.

Thus, the wretches here aroused pity. They would start work weighing fifty kilograms, at the mine entrance they weighed seventy, and when they came out, they exceeded a hundred.

This transformation was influenced by the air loaded with moisture and foreign elements, especially silica dust, plus the acetylene released by the carbide and the unburnt trinitrotoluene gases, the sulfur and phosphorus emitted by the pyrite and copper mineral; even the fungus-bacteria microorganisms that developed from the decomposition of biological waste of the wood material, plus the humidity that reached record levels, often exceeding ninety, even a hundred percent of the capacity, because there were ceilings that dripped, but there were special ones that flowed continuously; this totality of factors turned the recently emerged from the underground into scarecrows dripping water.

Aiming for the longest possible exploitation of physical capacities, they increased the clothing norm, or as doctor Astrit Delvina ironically said when he saw us dressed like that: “They threw the veil over us, for Hades!”

To reach the peak of performance and prolong the physical condition of the slave-mechanisms, a little more “fodder ” had to be added.

As a rule, they implemented a Spartan diet and reduced norms in prisons. If elsewhere they economized on quantity and quality to perfect the figures of potential enemies of the regime, in Spaç, it was fundamentally different: the enemies had to be dressed and fed differently, so they would be healthier, to turn them into useful and contributing factors to the prosperity of socialism; even though they later let them die like mangy dogs and buried them as such, in unmarked graves.

From what I had read in Reps-I’m referring to the regulation’s normative and the calculations on paper- the daily portion of a convict amounted to twenty-two old lek. But…, ah-ah, the reality was fundamentally different!

Let’s refer to the papers. Add to the above sum some extra expenses, such as: clothing treatment, medicines for medical service, police payments and free food for compulsory service soldiers, the account doubled, but still didn’t reach the price of a single bullet, which cost eighty old lek and was poured out without counting, to terrorize or kill someone.

Since I haven’t excelled in numbers and might fall into gross errors, I leave the floor to my friend, Ismet Boletini, as I try to give the daily recipe, which might serve as an amulet for today’s dietitians, to use on patients with excess fat.

The voluntary relinquishing of the study’s authorship gives me the right to move directly to the figures: The daily diet for workers included three meals, and for the rest, two. That is, the “parasites,” a category that grouped the elderly, chronic patients, those punished in camp cells, those isolated in detention centers, etc., in short, all those who did not work, for one reason or another.

Since the Party that guaranteed us free food was called the “Party of Labor,” I start with the workers whom it particularly loved, even though it often suffocated them with “love,” just like the compassionate mother who squeezes the child until… she takes their breath away. Workers enjoyed seven hundred grams of bread, although for months they received four hundred grams, and the rest, boiled potatoes, but at this point, the authorities referred to the valuable instruction of the “Enlightened Teacher,” comrade Enver, who preached: “The potato is bread and a meal!” /Memorie.al