By Esat Myftari

Memorie.al publishes the unknown story of Esat Myftari, originally from Peja, who was in high school benches when he was a member of a group of young boys who opposed the official Belgrade policy against the discriminatory policy against the Albanian population living in He started working as a journalist at “Rilindja” in Prishtina, from where he was proposed as a correspondent of the TANJUG Agency, but he refused and in 1963 he was forced to flee and come to Albania, with the intention of seeking help and support. from the mother country, for the clandestine organization of the “Boys of Peja”. Numerous vicissitudes in the mother country and continuous pursuit of the State Security since the time of studies in Tirana and the period when he served as an educator in the town of Shengjin and the villages of the Coast of Matë, where he was arrested in 1975, after he had officially requested repatriation to his homeland Kosovo, sentencing him to ten years in prison on charges of “agitation and prop agenda ”, which he suffered in the Spaç camp. The whole painful story of the journalist, publicist, researcher, translator, MP and diplomat, Esat Myftari, is described with literary mastery in his book, “Your death, my life” an autobiographical novel that has just come out from the Publishing House “Lena Graphic Desing” of Prishtina, and with the permission of the author, will be published in parts by Memorie.al

The unknown story of journalist, publicist and writer Esat Myftari

Esat Myftari was born on June 16, 1940, in the city of Peja in Kosovo, where his family originally came from. He completed his first elementary school education, 7-year-old and high school, in his hometown, completing them in 1959. Also. in 1959, Esat, a 19-year-old boy, began his studies at the Faculty of Law of the University of Belgrade. A lover of history and literature, he started writing at a young age when he was in the 7-year school benches and in the faculty period, he became a member of the Literary Club “Përpjekja” based in the Student City of “New Belgrade” , where he affirms himself quickly and from time to time, writes poems and critical literary views, but due to their content, does not send them for publication.

In 1961, after successfully passing the relevant competition, Esat started working as a journalist in the daily of the province of Kosovo, “Rilindja”, where he is assigned to cover the chronicle of the city of Pristina and the Kosovo Trade Unions. In the same year, he was offered a qualification scholarship at the Yugoslav TANJUG Agency, with the prospect of becoming a correspondent outside the then Yugoslavia. But his joy at the scholarship that was destined to send him to the outside world was quickly dashed, as the specialization offered to him was conditional on his membership in the Communist League of Serbia, which 20-year-old Esat refused. categorically.

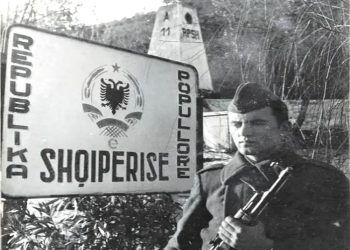

Meanwhile, in 1963, he participated in a group of young men who disagreed and were against the policy pursued by official Belgrade towards the Kosovo Albanians and wherever they were in their lands under Yugoslavia, and on behalf of the “Peja Clandestine Group”. , as their representative, crosses the border illegally and comes to Albania. Esat’s goal as a representative of the “Illegal group of boys of Peja”, was to establish contacts with the Albanian state and to seek various support and assistance, for the well-functioning of that group of young boys, which aimed to resist the discriminatory policy of official Belgrade to the Albanian population in Yugoslavia.

In 1974, some members of this group were arrested by the official authorities of the Yugoslav Ministry of Internal Affairs, accused of participating in the events of 1964, when the Albanian national flags were unfurled in the main cities of Kosovo and when they were taken strict police and judicial measures against them. The main motto of this mass movement, which was the first of its kind in post-war Kosovo, was the unification of Albanian lands with their “mother” state, Albania.

Meanwhile, Esat, who was in Albania, as well as some of his Kosovar emigrant compatriots in Albania, gained a right to study and in 1965, he began his studies at the Faculty of Natural Sciences in Tirana, in the “Bio-Chemistry” branch. After the third year of studies, disappointed by the official policy of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha and the treatment of Kosovar emigrants in Albania, who upon their arrival in their homeland, it seemed that “from the rain they had heavy hail” , interrupts his studies and requests repatriation!

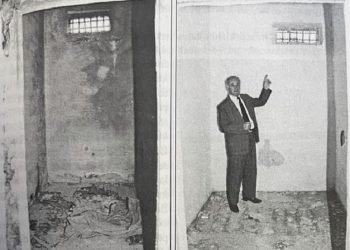

Of course, this was not approved by official Tirana and in 1969, Esat started working as a teacher in the 8-year school in the town of Shengjin, in the district of Lezha, where he worked until 1974, from where he was transferred to the village of Tale. of the Mata Coast, where he also worked diligently. As during his entire period of work and residence in the district of Lezha, Esat was regularly monitored by all means by the State Security organs, even in the school where it was said that he had been sent on purpose, as they feared an escape from his opportunity to go to Yugoslavia from Shengjin, he is arrested and sentenced to 10 years in prison, accused of “agitation and propaganda against the popular power”!

After serving his full sentence while serving his sentence in the Spaç camp, etc. (not benefiting from a single day of reduced sentence), Esat was released from political prison in 1985 and returned to the district of Lezha where he had worked and lived before the sentence and in 1986 , starts working as a worker in the Paper Factory in Lezha. That same year he started a family and then two sons were born.

In 1990, at the beginning of pluralism, Esat took an active part in the popular movements for the overthrow of the communist dictatorship in Albania and with the establishment of the branch of the Democratic Party for the district of Lezha, at the beginning of 1991, for his past and contribution. great at the beginning of those popular protests, he is elected secretary of that branch.

Also, as a result of that contribution, in the first pluralist elections of March 22, 1991, Esat was elected a member of the Democratic Party in the People’s Assembly, representing the voters of the Mata Coast, where he had worked as a teacher until the day of his arrest in 1975.

A year later, in the autumn of 1992, he was appointed Director of the Diaspora Directorate at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Albania, headed by the Minister, Alfred Serreqi. In that position, Esat worked diligently until 2000, when he was appointed diplomat at the Albanian Embassy in Riyadh, where he remained until his retirement.

Since that time, Esat has been devoted to his passion, writing, studies and translations and since 2011, he has started publishing several books, which have been welcomed by critics and readers, also because of their subject matter, as well as the variant of Gegërisht that he wrote them, which is very rare in Albanian publications of the mother country!

The first book published by Esat Myftari is “Emrush Myftari” (monograph), followed by: “Kosovo and Enver Hoxha” (study), “Political profile of Esat Mekuli” (monograph)

As well as “Your death, my life”, which is an autobiographical novel, where he has masterfully and chronologically described most of his life, from family and life in Kosovo as a high school student, escape to Albania , numerous vicissitudes from State Security surveillance and persecution, arrest, investigation, trial and deportation to Spaç prison.

All the events and everything described in the book “Your death, my life”, are real and the characters there are presented with their concrete names and surnames, while only those people who badly affected his life, (mainly, those of bodies of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of that time, such as operatives, investigators, police officers, heads of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Branch of Internal Affairs of Tropoja, Lezha, witnesses in his trial, etc.), the author was has only changed the names, giving them their real surnames.

Continued from the previous number

Excerpts from the book “Your death, my life”, author, Esat Myftari

Escape from Kosovo to Albania in 1963

Ridvani boarded the Peja-Gjakova bus at the Zall Bridge. He sat at the window in order to look once again at the two friends who accompanied him and the main promenade of the city – Korzon, where he went out with them every evening to see her absence. If at first their themes during these walks were varied and the transitions from one to the other kept the rhythm of age, in the last two months in their discourse only one theme prevailed: that of the best possible organization of the resistance. The previous eroticism and flirtations had been pushed somewhere far away – it even seemed a bit embarrassing to deal with such light and grunting worries in the face of this fundamental and vital. And, as the bus passed through the center, he opened his eyes wide to escape any detail: he saw the two comrades leaning against the stand of the advertising stands who raised their hands in farewell and the other multitude of peers gave after their nocturnal habit. Everything was like the unreal game that he himself had asked for but that now, in the making, caused a stab wound in the heart. He realized that he had stepped into the vortex of politics with both feet, even in its most dangerous ramifications.

His companion – whom he had met a few hours earlier in the large city park – was sitting two chairs in front of him on the other side. They had left him with words not to communicate between the ved during the whole trip. It was assumed that such a line traversing the mountains bordering Albania could always have a passenger observer. After crossing the Stone Bridge and entering the straight road to Gjakova, Ridvani pulled the curtain over the window and closed his eyes. He was pretending to be asleep, but he was actually guessing at all the possible surprises. He also remembered the two letters of his cousin that spoke of his escape, exactly this trace in those distant times of the monarchy, a mission that was secretly organized by the Albanian consul in Skopje. But they, then, were almost all minors, who went to Albania for their education in their mother tongue. But he was leaving with other intentions: he had in mind the main request for the correction of several mistakes that, if you merged into a single one, it turned out that he had taken the courage to convey a very delicate message about their fate to measure. For this purpose, he had inserted into the brain the names of network nodes that, perhaps, one day, could go down in history. Instead, he risked being labeled an adventurer, or a puppet, whose strings had attracted others.

How they left behind Deçan, a large village that in recent years was taking on the appearance of a popular town, with mountains full of pine trees in the background, the monastery, the pool, the sparkling water, the resorts – these objects that were making the epicenter of entertainment and education aesthetic. The companion made some gestures that made Ridvan understand that they would come down soon. And when he read the table with note Junik, the bus stopped. They went out one after the other without turning their heads back or sideways. The bus resumed and they were covered by night owls and tree trunks along the side of the road. It was only when they were assured that no one near them was breathing and that no suspicious movement or noise was heard, that they joined together. I prekun, Ridvani said:

– How is this world: my babe grandmother comes from Junik, but I myself have never been here.

– Eh, Junik, what a story he has! – said the companion with a sigh

Ridvani wanted to continue the conversation and started, but he did not leave:

“Ridvan,” he whispered, “now I have to go home every minute.” Until I returned, you huddled somewhere in the grove and waited for me.

Ridvani went and leaned on a pine tree with his face back from the companion’s house. It was illuminated by a faint lamp, and its outlines were barely discernible. The mediator, who had found this companion, had assured him that he had given living proof of loyalty and not just once. However, only the beginnings happen, in the middle of all that forest and in a completely unknown environment, with the unnatural silence of the big village – the night is not over! – his concern did not seem in vain. So much so that the guide was quite late, and his house was not far away. In the meanwhile, as the waiting minutes were lengthening, he suddenly heard the question in a low voice behind his back: was I late?

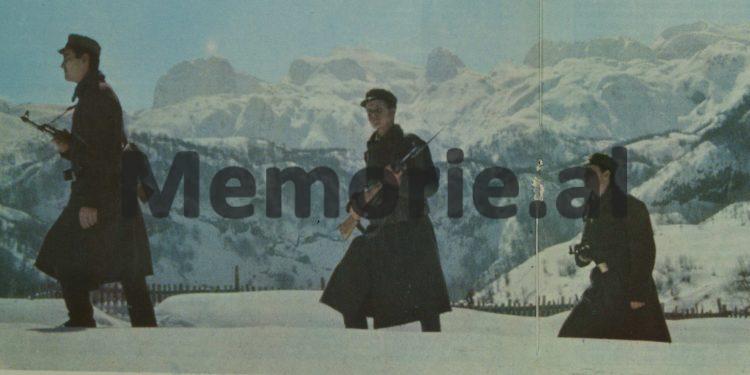

Ridvani followed the path he showed him by hand. After a good stretch of road, in the deep, dull stillness of the forest, the companion beckons them to stop. “Listen here,” he said, “now we are not far from the border. In the name of God, we will arrive without any problem, so I am telling you how you acted. When you are right on the border, walk hand in hand, with controlled movements. The soft belt of earth will make the work easier for them, but that belt is made for tracks and for the dog and not to help the offender, so be careful. As soon as you cross the border, two or three hundred steps away from it, right behind the first hill, you will see a small house like a barricade. And as you approach the door, call out: O lord of the house, do you want a guest? Of course, you have to wait a while because the answer does not come immediately.

Ridvani quietly listened to the advice and did not find it appropriate to tease him with any questions.

Fortunately, the clear sky began to be covered with rapid clouds. And when they entered the hailstorm, it rained lightly, and the leaves became thick. And the companion, who was scrutinizing his every reaction, was really enthusiastic. with him. It had seldom happened to accompany a young man to Albania who obeyed his instructions with so much discipline throughout the itinerary. Even when he met them wandering through a fairly open freedom, with the full inn above them, he had told him to go first, and he would shave his back from a well, technically this is a fairy tale, because with a beret he was holding in his hand and it happened among those many and dense trees, Ridvani was completely defenseless. At the first moment, Ridvani thought that he had not fallen into the trap and as he was taking his steps through the grass and fern, he said to himself: Albanian! ” But none of these black and sensational imaginations of his happened: he went back into the forest and, after a while, his companion came to his side, who rubbed his arm and whispered to him, “Congratulations, boy! ”

As they parted, quite close to the target, they choked without saying a word. The companion disappeared as if by magic in the deep darkness, while Ridvani gathered his forces and, after taking a few steps, the famous border band came out, about whom he had heard spoken in big words during the preparations for the escape. He lay on the ground and froze like a frog, witty and with astonishing clarity of mind. He passed the belt simply quickly.

Escort by soldiers and interrogation at the border post

When he stepped on the land of the Republic of Albania, he said with obvious relief: what was this job?! His whole being was permeated by a sense of pride that he had proven himself to be brave. And when he climbed the low hill, as the ritual wanted, he turned his face to Kosovo. He shuddered. Only now did he realize that he had left behind, God knows how long, birthplace, parents, brother and friends, so that the century of his separation from them was starting right there.

As he approached the hut, he uttered the formula aloud. It was midnight and there was a cold silence all around. True, no one answered, but he already knew the scenario, so he went and sat down on the bench next to the door. He took out his peace and lit a cigarette, a sign that he had come with good intentions.

After about half an hour, while he was wondering about the delay of the border guards, he suddenly heard a savage and commanding cry: “Hands up!” Immediately after that, from the back of the house, the platoon with automatic weapons was set up. Ridvan was brought to his feet quite calmly. One of them approached him and checked him up and down, tue e touch with both hands everywhere, without point of care. After that, he ordered.

– Walk and keep your hands behind your head!

The whole scene seemed a bit absurd to Ridvan: we surrendered without weapons, why should he be treated as a prisoner of war? He was staring at the six soldiers who were divided on both sides and almost unconsciously said:

– Does this measure make sense?!

Their prince, to whom the age could not be discerned in the night sky, gave the unexpected answer:

– You are right!

Then Ridvani, without waiting for his second thought, lowered his hands.

The road was close: it too was small and without any architecture to study. Yes, there was light, though not strong. In the office, or in that office imitation, he was met by a middle-aged man with a shoulder and a frequent mustache.

– Welcome to us, brave of Kosovo! – he said and extended his hand.

– Good to see you! – Ridvani returned.

They approached the chair in front of the receptionist in civilian clothes, which indicated that it was probably not effective at the border crossing.

– I have been by your side and I know them well. They are beautiful places, really beautiful. The Serbs abducted us with disbelief, but we will still keep ours. I remember that you also came for this ideal.

These warm words, after that travel strain of those military cries, were sounding friendly.

– I would be happy if I help a little.

– Not a little, but I hope you will help a lot – said the host and looked at his watch. It was going two. – You will surely be tired, so now you can go to the alcove in front of my office and fall asleep. Tomorrow, the day for the sun and with a clear mind, we will continue the chatter.

“Yes, I really need a break,” Ridvani said.

But when he entered the alcove, he was terrified: the window had no glass, two planks were placed across its space, and the rest was covered with sticky newspapers. A small bookcase was stuck to the wall. After locking the door, he slammed it against the straw mattress, as it were in his clothes, until he somehow recovered. The change of circumstances was so frantic in such a short unit of time that he doubted he was in a dream. He begged for sleep, but it was not coming. Then he took a look at the bookcase. He was amazed when he found the summary of the documents of the declaration of independence, in Albanian and French. It was released on him like a hungry man, because such material, when he was there – now in his distant Kosovo – was followed like a mouse by all infections.

The cover of the book had a simple but meaningful design: The old man of Vlora with his European costume of the late Ottoman period, with the red religion on top, with a nice reading that fit well kissed on the stuffed body, of the time when it was weighty in their parliament and above on the right wing the national flag waving over the ruins of a finished era, images that gave it a little heart for the step it had just taken. And while he was wandering through those texts with the style of telegrams and reports, he built carefully, his eyelids were slowly being rolled up until he fell asleep as he was, they crouched a little on the book.

At that moment, they knocked on the door and invited him to a breakfast with the staff. Around the table were all sitting. Served with pilaf and yogurt. Ridvani was barely following the pilaf that smelled of unroasted sunflower oil. But, fortunately, there was the chicken yoghurt that gave the flavor its final aroma and refreshed its mouth.

When they finished eating, the dishes, plates, and spoons made of thick, unprocessed aluminum, reminiscent of the childhood stage of industrial development, were removed. The table was cleaned with a crushed sponge on the side and then only Ridvani was left with the person in civilian clothes.

Did you rest at all? he asked.

“Something,” Ridvani replied, “but I read more parts of the book of independence documents.” I was reasoning last night: such a book, which I found here at one point, as I was told, the dead, there of us cannot be found even in the central library.

– That’s right – the interlocutor replied – last night I said that I was in Kosovo. I finished high school in Shkodra, but then, due to urgent needs, they called me capable of teaching, so they put me in the contingent created to help the Albanian school there. And I saw with my own eyes that the Albanian book had cholera.

– Of course, the situation has now changed radically. But at one point of control it has remained strict: any book of documents that genuinely proves the efforts for Albanian Kosovo or the demolition of the myth about the Serbian Middle Ages in Kosovo, is ruthlessly followed.

– However, they are in vain – the host said – we have already secured the channels that undermine their temporary hegemony.

“You’re making me happy,” Ridvan said.

– You are young and the battlefield belongs to your generation. In this respect, I covet it. And my generation, as a Tropojan that I am, alas, has no choice but to go to the top of the mountains and look at Gjakova, to extinguish an old commodity.

After these general words and with a very personal spirit, the host, who was still not presenting himself with his name and surname, said:

– I received the order from the center to forward it to Bajram Curri today. You will stay there for a few days and then they will come from Tirana to take you.

– Thank you!

– There you will meet competent people who know these jobs well.

In the Branch of Internal Affairs of the city “Bajmar Curri”

Ridvani felt relieved. So, they separated him a few days from the moment he would trespass in his bloody city.

To accompany him to Bajram Curri, a soldier a little taller than himself and with a good body was assigned to him. The machine gun fit him nicely, it looked like a half toy on his muscular arm. But since they did not have a car available, they had to travel a good part of the way on foot until they came across an occasional vehicle. Ridvani, though tired and sleepless, was not giving himself up. He was even glad that they would walk, because he would have the opportunity to enjoy the landscape of the first autumn.

Along the way, the soldier showed signs of approach:

– My name is Hekuran and I am from Skrapar. You are the first Kosovar I meet because I have been here for a few months. We were told that they would take you to Tirana. You are lucky, because Tirana is another world. Life is made there, you will see. Where are you from?

– From Peja. My name is Ridvan.

– Is Peja a big city?

– About fifty thousand.

– All Albanians?

– No, we are to mix, but, of course, most are ours.

– Is it nice at all?

– Yes, a lot.

– Did you have any enmity that you left, sir?

– Jo.

– Excuse me for the curiosity.

– Nothing, I owe small talk and the road can be long.

– Do not worry, a car will appear soon.

But it took them another hour to walk until a truck with people came out of the road above the body. They boarded and settled on the fall and were taken out to the Valbona River. The three men, leaning on their shovels, with their faces fluttering and their gazes somewhat sullen, were not making wine with their mouths. They were looking at this young man, wearing a suit and tie and with a face like an adult child, and who knows what they were thinking. Once upon a time, one of them, as usual, asked the routine question:

– Where to have it, boy?

“From Peja,” replied Ridvani.

– From Peja mrena?

– Yes.

Then they were again enveloped in their silence. And Ridvani, this first meeting with Albanian civilians, without any external attraction, was frightening him more than those masses of rocks that reflected on the horizon and that seemed as if from moment to moment they would collapse on their pride. But what began to pierce his brain in a special way was the conformity of their appearance with the descriptions of those whom, when he was in his homeland, he had described as lies or malicious excesses.

When we entered the city, he greeted us and congratulated us:

– Good luck to you in coming to Albania and good luck.

The other side of him, the one who said that, could not bear it without being stung:

– It seems that they did not like Peja’s cannon apples!

Ridvan was swallowed up in gas: it was an arrow that had touched the beginning of his fierce disappointment.

– It seems! – Ridvani returned, without any anger.

The car stopped in front of a two-story building. The soldier gestures for Ridvan to come down. He greeted the workers, said “make me halal” and threw himself skillfully on the ground. They accompanied him with a stream of loud words of blessing and proceeded to their destination.

On the front of the building, on an oval blue tin, was written: Interior Branch – Bajram Curri. The soldier told Ridvan to walk beside him so he would not look like he was caught. However, the looks of the few citizens who were there first were full of sympathy and almost pity for him. How did he know what the long experience told them? It was not in vain that it was called Gjakova Mountain, the storms of the time had always unloaded the strangest fate of Kosovars.

A military man with the rank of major received them in the Branch. Everything smelled of preparation, perhaps even its excessive and unreasonable seriousness. Even his handshake was weak and hard.

They placed him in a small room, with a window overlooking the street but with a large lamp that did not go out day and night. In the corner of the room, he noticed a wooden bed on which were placed some unbreakable blankets, and in the middle, just below the lamp, was a narrow table with two chairs on the side. Although they were tired, they could hardly sleep. After a while, perhaps in the middle of his first sleep, a shadow approached him with light steps and he jumped on him to tie him with a big, thick rope. Ridvani gave and took terrified to oppose him, but his limbs were not obeying him, they were rendered and hardened as if they were pieces of wood. But the situation came to an end when the shadow began to grip his throat. Then he cried out for help.

Finally, he fell asleep and saw that his body was left in sweat. He realized that the night had violated him. As he was sweating, he got up and washed his upper body with cold tap water, rubbed himself with a towel, and once, later, he fell into a restful sleep.

The next morning, the major came. When they sat down, he announced that he had come to get his first statements. He pulled out a form and pen from the thin folder and opened some other format papers on the table. Ridvani gave his generals, but when the major asked him why he had come and what his goals or demands were, Ridvani stopped and thought.

– Yes, Mr. Myftari – mentioned the major.

– I am instructed to talk about this point only with the center – said Ridvani calmly.

Indeed, this was an immediate invention of Ridvan because he did not anticipate the band’s affairs going through several doors.

The major stepped in: apparently, he also did not know how to act, if the rules had to be obeyed or he had to do with an exception that, if he insisted on it, could cost him later.

– Agreed, – finally said the Major, – I am noting here that the border trespasser, refuses to answer this question. Memorie.al

Continues tomorrow