From Xvehir Gradica

Memorie.al / Three members of the Hasani family from Pista e Shëmrie e Kukës, who today live in Saint Vlash of Durrës, have spent a century in camps surrounded by barbed wire and in forced labor. Decisions after decisions from military courts, popular councils of villages and neighborhoods, filled the files against Mustaf Hasan’s family, because he and his tribe were nationalists and did not like communism. Agim Hasani, the only son of parents Mustaf and Aishe Hasani, born and raised in the internment camp in Savër, Lushnje, say that the persecution began in 1945, and did not end until September 1991. Full 100 years of exile, have three family members: father, mother and himself.

Fines

On June 14, 1946, the military court of Shkodra sentenced to prison six of the organizers of the “Cam Connection”, a connection that aimed to organize the armed revolt in the north of Albania. Among the convicts was Agim’s grandfather, Hysen Mustaf Hasani, and uncle, Halil Hasani, while his father managed not to de-conspiracy, escaping imprisonment but not exile. The accusation that weighed on them was that of “organizing the armed uprising for the violent overthrow of the power of the people and cooperation with the nationalists”, described as enemies of the communist regime.

Çami Mountain is located in Mngulle, near the gorge of Srriçe in Kukës, on the side of Sëmria on the border with Mirdita. The organizers of the connection had their center in Shkodër and from there the instructions for everything were received. During his confession, Agimi testifies that: “Based on the investigative file, at the time when the outbreak of the uprising was expected, which had been prepared for more than a year, its leaders fell one after the other in the hands of the regime of the time.” According to his father, he remembers that for several months they were eavesdropped and followed by some lying villagers who then served as spies. The military court sentenced the six leaders:

- Ymer Bardhoshi from Laçaj, with life imprisonment.

- Mustafa Ymer Aga from Pista, with 30 years in prison.

- Halil Halil Hasani from Pista, with 20 years in prison.

- Bislim Elezi from Shikaj, with 30 years in prison.

- Ramë Bajrami from Qaf Lekë Meta, with 20 years in prison.

- Hysen Mustaf Hasani, with 10 years in prison.

Mustaf Hysen Hasani and several other villagers were not in that surrounded house on the night of the arrest of the main leaders. They escaped without being captured also due to the fact that the leaders of the uprising did not deconspiratory the circle of members of the “Cham Connection”. None of the convicts had the opportunity to deny the accusation, since during the confrontation with the communist forces of the Pursuit, many documents, materials and decisions about the armed uprising in the North fell into the hands of the latter. But Mustafa and others would not escape the persecution. The fact that Hyseni and Halili were convicted was enough to label them all as “enemies of the communist government”.

The Follow-up Forces also had accurate information about Hysen Hasan’s frequent meetings with the head of nationalism in Kukës, Mirdita, Mat, Dibër and Pukë. One of them, Muharrem Bajraktari, had shelter and support with weapons, food and clothes in the tower of Hysen Hasan. In 1943, the villagers of Pista, Shëmria, Mngulla, Srriçe, Vrish and Qaf Shllak, ambushed two Italian cars loaded with weapons on the road. They took their weapons, which they hid on the ground floor of Hysen Hasan’s house. Whenever Muharrem Bajraktari needed weapons, he went himself or sent his loyalists to the tower of Hasanaj.

Cham connection

Agimi shows that the military court of Shkodra had gathered a lot of information to destroy the group of “Lidhje e Chami”. The latter had cooperation with the “Albanian Union” organization, also based in Shkodër. Because Halil Hasani was educated in Rome, Italy as a soldier, the “Chami Connection” had assigned the commands and this fact was learned by the investigators, through the depositions made by the lying villagers of the area. Halil knew Serbian, Arabic, French, Italian and English. During his studies in Prizren, he learned Serbian and Arabic then went to soldier in Saranda.

During the period of the Italian occupation, he, along with several other soldiers, had killed several Italian soldiers. After this action, they left, but the Italians collected and selected them. Halil was educated and of high stature. These two details were taken into account by the Italians, who started with studies in Rome. At the end of his studies, according to witnesses, he refused to take the oath for King Victor Emmanuel III, so he did not wear the uniform. As soon as he returned to Albania, he was placed on the side of the nationalist resistance and became an active participant.

The twenty years of prison sentence by the military court of Shkodra, he suffered in the Castle of Gjirokastra, where mostly all educated people in the West were sent to be exterminated. Based on archival documents, it is known that Halili spent all the years in a humid cell and water flowed over his head day and night, so he became seriously ill, only to die a year after being released from prison. But the punishments and deportations are not over for that family. Hysen Hasani, after completing 10 years in prison, escaped to Kosovo. In Has, while trying to cross the border with a local family, he was ambushed by the Pursuit and Border Forces. As soon as he gets to the other side of the border, he sees that the woman, who before had a child in her hand, was withered.

The child had fallen from their hands at night, during the time when they fled in alarm to escape the border forces. The couple from Has, had tried to check in the dark, but they had not found the child, and as the voices of the Pursuit Force approached, they left the baby and crossed the border. Hyseni returns to Albanian land and was able to find the little child. His action was dictated, but efforts to capture and isolate him failed. So he was able to settle in Prizren, where he died a few years later.

How did we survive in the camps of communism?!

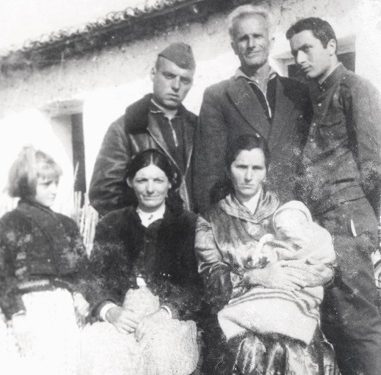

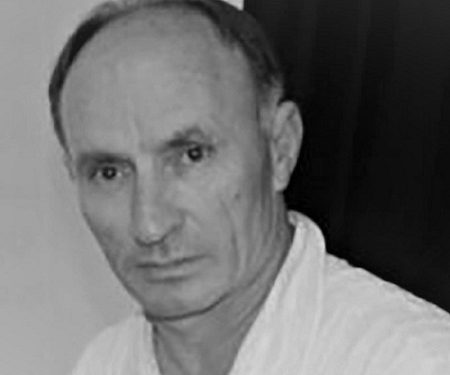

In a briefcase, Agimi carefully keeps all the documents and photos related to the period of barbaric persecution by the communist dictatorship. They are all there. “It is the whole life of the father, mother, grandfather, brother, uncles, cousins convicted, with tens of years in prison and tens and tens of years of exile, just because they were against the communist regime, just because they loved ethnic Albania and not communism”. – says Agimi. Mustafa, his father, passed away a few years ago, but in this suitcase, he has stored not only photos, but also written notes.

Mustafa had completed his studies at the Burrell Boarding School, during the Bird Monarchy, so he was among the few young people of the time with a secondary education. Agimi shows that Mustafa has left very interesting notes, as in them he also talks about the “Chami Connection”, a connection extending throughout the North of Albania, which aimed to organize the armed overthrow of the communist government; relations with nationalists heard, as; Muharrem Bajraktari, Mark Gjon Markaj, Pashuk Biba, etc.; military court decisions; life in the internment camps and suffering in cells and prisons, his relatives.

Agimi’s parents suffered in the internment camps in Tepelena, Porto Palermo, Berat, Kamëz and Lushnje. By browsing those memories, Agimi confesses that the exile gave him another opportunity, which he calls luck. There in Tepelena, Berat and Lushnjë they met and lived with people of large families from the North and South, who had made a name for themselves since the time of the war, with the Turks and Slavs, Greeks, Italians and Germans, until the violent opposition of communist regime.

“Father has instructed me to keep in touch with the grandsons of these families, as they are the pure blood of Albanians, unsullied by crimes, espionage, betrayals”, – asserts Agimi, who also has his own memories, after was born and lived in the internment camp in Savër, Lushnja, until the age of 26. There he extinguished many dreams of his youth, there he also experienced contempt for people clothed in power, parts of which he tells us in this short interview, which we are publishing in this article.

Mr. Agim, your parents spent most of their lives in internment camps, while you were born there. How do you remember those years?

Father and mother came from a nationalist family. My father was from the Kukes Health Track, and my mother, from the Gjoçaj family of Tropoja. This made the communist regime look at them with the eyes of the enemy, even though their tribe had fought against the Serbs, the Montenegrins and the Italian invaders. It was important for the communist regime to extinguish families with strong roots of nationalism and to educate people, servants of the regime. After grandfather Hyseni and uncle Halili were arrested and put in prison, the fate of their tribe was predetermined, to be very difficult and with a lot of suffering. Mustafa, the father, was interned, moving from one camp to another, for 27 years.

He worked all day until the evening and did not receive a single penny, as they were isolation and forced labor camps. All the sweat was exchanged for a piece of bread, in the big cauldron of tasteless camp food. In Savër of Lushnja, I met my mother, Aishen, who was suffering in exile since 1946. The reason for her punishment was the alignment of the tribe of Gjoçaj, on the side of resistance against communism. The mother herself took the gun and fought. After he was caught, he stayed in the dungeon for a year and from there, he was deported to Tepelena, Berat and, finally, to Lushnja. When they sent her to Lushnja, the mother took shelter in the barrack of Pashke Sokol from Topoja, who was interned with her children, but without any male member of the house.

In the same camp was Rrok Konti, my father’s friend who was married to Pashka’s daughter. Since he knew my mother, from the entrances and exits to the Sokols, he acted as a mediator and engaged my father to Aisha. It was sometime in 1963. They tried to betroth my mother several times in the camp, but she refused. She did not want to tie the knot with weak families, while those who pushed her to marry, aimed precisely to break her tribe, by marrying her in a door without any patriotic tradition. I was born in exile and I am an only child, from Mustafa’s crown with Aisha. My mother did 45 years of internment, my father another 27 years, while I did 26 years.

Together, a century in the camps built to suffer horrors and depersonalize Albanians. I also have a brother from my father, his name is Ali Hasani. In order not to have our fate, father put him under the guardianship of his uncle, in Pistë, and then of his uncles, in Fushë-Arres, with the Bislim Bajram Ahmetaj family. He studied very well and finished secondary and high school (Pedagogical), in Shkodër. While I was lucky enough to complete my higher studies, a few years later, only after the fall of the communist regime. As soon as we were released, in September of 1991, my father told me that I had to go to high school, and so I did, wasting no time at all.

What do you remember from the period of years in exile?

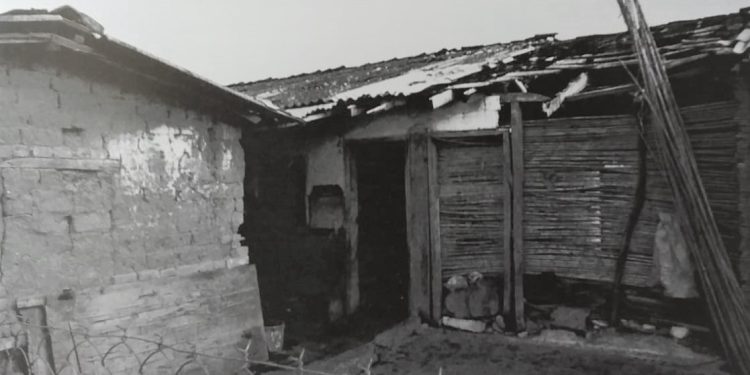

A lot of things. Even though the years go by, nothing is erased, as they have left traces, even very deep ones. They are bitter memories, filled with extreme poverty, misery, even starvation, contempt and macabre events. The camps were surrounded by barbed wire. At the entrance gate, there were checkpoints, armed guards, highly indoctrinated and criminalized people, ready to add bullets to the body of any persecuted person. People slept in silos, men and women, without doors or windows. When I was born, my parents lived in a 3 m room with 3.m. built of reeds and covered with thatch. But the parents, separately, unknown to each other at the time, also lived in the camp of Tepelena and Berat. I say this because I have many memories from them.

All the powerful men and boys in the Tepelena camp were forced to dig up to 10 deep pits to bury the internees who died every day, mostly from hunger, but also from the diseases that were wreaking havoc in the camp, such as typhus, malaria, etc. Baba told me that this story, that is the one of being forced to dig pits for graves, lasted a long time. After the hill was filled with the dead, the men were again forced to dig graves. This time on the river bed, in the gravel, in order to bury the dead of the camp. Tepelena was involved in the famine epidemic. Many internees died every day: children, women, and the elderly.

The camp was rapidly being exterminated. One winter, the river swelled and all the bones were swept away by the rushing water. In another case, my mother told me that during the transport by car, to the internment camp in Berat, the soldiers beat a merchant of the city in the middle of the road, with the butt of their weapons and with kicks. They had found his hidden gold and took it from him, dragging it along the street. They beat him until he died. There are other strange truths. Nikollë Mërnaçi from Vermoshi Shkodra was also exiled. He had served 10 years in prison, after his family members, including his mother, had escaped. His mother about 90 years old in America went and voted in the next election for the President of the USA.

A newspaper wrote: “The Albanian mother votes for the American president”. Immediately, the Albanian State Security checks Nikola’s apartment in Vermosh and they find a ‘Bible’ and Fishta’s work “Lahuta e malcis”. They arrest him and sentence him to another 10 years in prison. Both books were called, forbidden and hostile literature. There were also unexpected things in the camp. The elderly woman, Vocërr Sherifja, prayed in the name of her brother’s blood, whose name was Shpend Sherifaj, saying; “for the blood of Shpend Sheriff…”!

The command of the internment camp gathers some bought peasants, communists, brigadiers, free people, spies and the secretary of the party, together with the chairman of the Council, and hold a meeting with them in the camp hall. They seek to deny the sister, to swear in the name of the blood of the brother and this for the reason that the Sheriff had escaped. “Why do you swear in the name of the enemy of the people”, – the provocateurs asked and pressured him, who then became the object not only of swearing and cursing Vocërr Sherifaj, but were also punched by her.

What were your relations with the families inside the camp?

We had very good connections and relations, with most of those who were from nationalist families. There we met and made strong friendships with the son and daughters of Muharrem Bajraktar, people from Abaz Kup, the Miraka family, Rrok Kontin, the brothers from Vau i Spas, Sadik, Avdi and Tahir Neza; Avdi Cahanin, the son of Xelal Staraveckas, Haxhi Brahim, Prelë Vatnika, Azem Neza, Gëzim Kullën, the Belishova family, Rreshit e Hajrie Mulleti, Kaloshte, Dine Dinen, Peposhtë e Gjutët, the family of Nikë Sokol, the Ndreallars of Slova di Dibra, and others.

Some were family members, others separated, only the men and, only the women, with children. We talked, without the fear that someone would report us. They came from a family with a strong patriotic background and in conversations; the first and last topics were exactly such issues. There they told stories of the war with foreigners, about the names of legendary figures, about the customs and traditions of the areas they came from.

In the internment camps, we suffered like a snake under a stone, but from those others, I call myself lucky, that I was able to live with those men and those people, who came from Albanian nationalist families. Many of them were educated in the West. They were without hope for life and the future, but they did not give up. They remained invincible; they didn’t complain about anything, they didn’t want to provoke the investigators and the people of the communist government, to rejoice in the pain they caused us.

Children’s education has been a problem for the category of interned families. How did your schooling go?

I did my 8-year education in Savër, secondary school in Lushnjë. In the fifth grade, teacher Ismail Turdiu, former lecturer at the University of Tirana, came to us. His granddaughter, Silva Turdiu, was engaged to the son of the prime minister of the time, Mehmet Shehu, so Turdiu was transferred and expelled to Lushnja, to an 8-year school. He taught me mathematics, physics and geometry. All those who were lucky enough to have a teacher Ismail Turdiu, became educated and skilled in life. They finished high school and serve in several sectors.

Vangjel Prifti also taught me the subject of biology during my internment. He was also a good teacher. I passed all the subjects with a very good grade, while the education subject, who was given to me by the director, Osman Kasapi, an evil man with vices, a communist and a bad spy, he graded me as a 6 or 7. Not that I didn’t learn it, but he has expressed it many times, that we internees could not be evaluated with a good grade. In the eighth grade exams, Turdiu insisted that I be graded 10, while Kasapi told the committee that; you can’t get a good grade for the sons of the enemies of power.

The camp nurse was Lenka Çuko’s sister, her name was Zoge Velia. She helped me and intervened to go to high school in Lushnja, where I also finished high school. During my school years, I remember not being allowed to attend youth organization meetings because I did not have a youth tessa. In such cases, the teacher would take me out. I didn’t even go to the dances, because I didn’t want to be embarrassed when I was kicked out unwillingly. The memories are countless. In one case, I remember that my friends and teachers started asking me what connection I had with Sinan Hasan, the politician of Yugoslavia at that time.

Actually, I told them that I had relatives in Kosovo, but I didn’t know Sinan Hasan. Once it came to the tip of my nose and I told my friends that I have a close member of the tribe. Sinan Hasani, as I later learned, had been a partisan, captured by the Germans, interned in the Nazi camp of Vienna in Austria and, after his release, also made a career in politics, reaching the leadership forums of the Yugoslav Communist League, until the President of Yugoslavia at that time, after the death of Tito. My statement impressed everyone and even the teachers began to question me. Although I was the type not to worry about their words, I realized that I was in for a rough ride.

The youth organization and the People’s Council of the village also denied me the right to play football with the youth of the “Traktori” team from Lushnja. I had a great desire for the sport of football and the coach, without knowing my biography, gave me the bag, T-shirt, overalls and shoes. But it didn’t last long. A friend of mine came to me and told me that the coach wanted me to return his sports clothes and leave, as the village council had written a rejection letter. The letter bore the signature of the mayor of Savër village, Mihal Llazi, who wrote that, as a family, we were enemies of the people.

After finishing high school, you started working and then doing military service…?

We were exiled and we were convinced that only hard work awaited us. For 2-3 years, I worked at Savra’s farm in Lushnja. There were several camps within the district of Lushnja, such as; Savër, Plow, Gradishtë, Dusk, Cermë, Dzhazë and Rrapëz. They sent us once to a brigade center and another time to the other center, to hard work.

And I did the army in 1985-’87 in the engineering department, in Shelcan of Elbasan, opening tunnels. We were all politically persecuted and no one had mercy for us. I have completed the army without touching a weapon. They didn’t trust us, they only gave us picks and shovels. We would return from work, tired and impatient, waiting for a piece of bread, which kept my breath alive.

The soup pots were unwashed and two palms of red gravel. Soup was cooked there. The rice and pasta were full of flies and mouse droppings. Like it or not, this was our food. There, in our department, a rebel-type boy came to us, from a family from Shkodra, who had 11 communists inside. They had brought him for education. One day, he tells a friend that he was going to escape. The comrade tells the battalion operative. Astri was called the operative, he was from Korça.

Shkodran was followed in every step he took. Together with the friend, who had sold it to the operative, they leave the city of Elbasan. Those who followed him, waited for the escape, while Shkodran, as soon as he learned that the conspiracy had been de-conspired, ran to a gun with corn. As you exit the other side of the plot, you find yourself on the motorway. Astrit followed behind. The soldier from Shkodra was walking, turning his head and, seeing that it was impossible to escape, he jumped into the tires of a car and died…! Memorie.al