By Mehmet Biber

Second part

– “Albania, alone in front of the world” – National Geographic – 1980

Memorie.al / “Let’s accomplish all the tasks and break the blockade”, is written in a slogan in the Albanian city of Shkodra – but Albania’s isolation from the world is simply the result of its internal politics. Without allies and surrounded by states that have historically had ambitions for its land, Albania has organized itself in such a way that it will succeed on its own, under the strict dictates of Enver Hoxha, who has been in power for 36 years. The symbols of the pickaxe and the rifle predominate in public places. Hoxha, a dogmatic Marxist-Leninist, in 1961 severed relations with the Soviet Union, which he considered “revisionist”, and strengthened ties with China two years later. The road to succeed alone is a difficult road. Cars are prohibited in this country, so Albanians prefer to go this way, riding a bicycle.

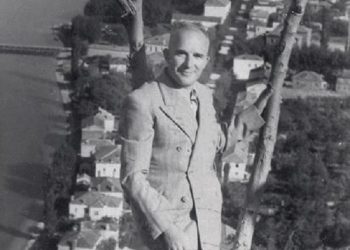

Journalist visits are quite rare. Last year, Mehmet Biber, a Turkish photographer living in Istanbul, was able to secure a visa just a few months after journalist Sami Kohen, another Istanbul resident, had finished a visit there.

From the conversations with Mr. Kohen and his personal impressions, Mr. Biber brought us this report, which is the first full report about Albania, published in American magazines, for many years.

Continues from last issue

The report of the Turkish journalist, Mehmet Biber

THE STATE PROHIBITS “OPIUM FOR THE PEOPLE”

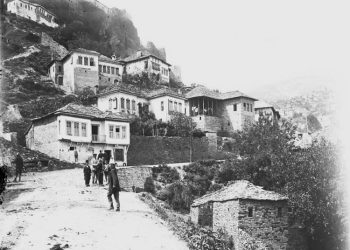

The rain had turned Lake Shkodra gray and wrapped the Northern Alps that watch over the border with Montenegro like a shroud. Along the bed of the lake which is navigable to the Adriatic Sea, lies Shkodra, the old capital of Illyria.

Above it, like a stone that protects it, rises a medieval castle that brings to mind the Venetian masters. In one of the parks, a monument has been erected to honor five partisans who sacrificed themselves, stopping 300 Nazi invaders…! (?!) Next to this monument, there was also the Museum of Atheism, which I was taken to visit.

Under Marx’s slogan “Religion is opium for the people”, the director, a cold, harsh-voiced guy dressed in gray, told me that religion had always prevented Albania’s independence.

Since Turks identified nationality with religious affiliation, Albanian Muslims (almost 70% of the population) were considered Turks. Orthodox Christians (about 20 percent) were called Greek and Catholics were called Latin.

Religious services were not held in the Albanian language, which was prohibited and did not even have its own alphabet, until 1908, but were held in three foreign languages: Arabic, Greek and Latin.

“During the war for the construction of the Albanian nation” – he continued, while showing me the stands with the abuses of the clergy, – “the churches served as a fifth column for fascism, imperialism and counter-revolution”.

Hoxha’s regime executed the clergy, sent them to concentration camps or made them do “productive work”. Other communist countries tried to bend religion; Albania banned it, declaring itself in 1967 as “the first atheist state in the world”.

Each of the 2,169 mosques, churches, monasteries and other centers of “obscurantism and mysticism” were closed, wiped off the face of the earth, or transformed into gymnasiums, clinics, warehouses or stables. The Great Cathedral of Shkodra, today, is shaken by the screams of 2000 basketball fans.

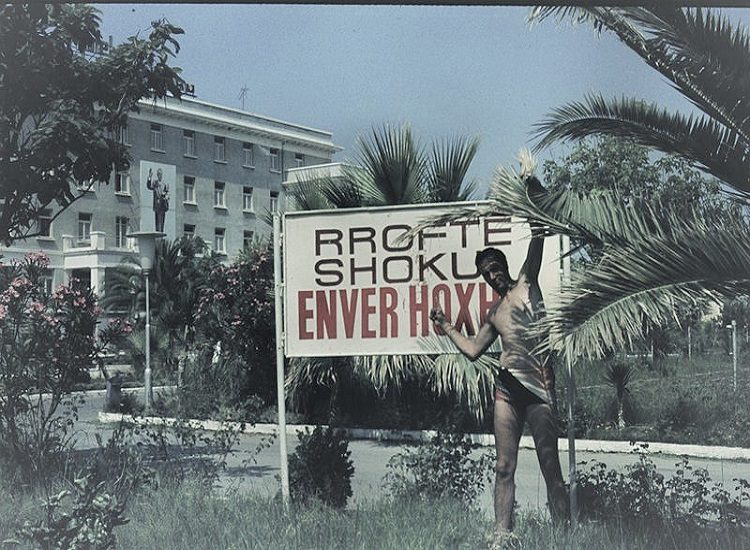

The new generation of Albania only knows atheism. Belief in Marxism-Leninism has replaced religious belief. Enver Hoxha’s books published in newspapers, broadcast on radio and TV, quoted for slogans serve as the New Testament. Hoxha is revered as the Messiah – infinitely smart, far-sighted and benevolent, but also ruthless towards his enemies.

THE LEADER RAISED IN HEAVEN

Living separated from others in a military-guarded area on the side of “Dëshmorët e Kombit” Boulevard, and driving around in a “Mercedes” with curtains, Enver Hoxha is everywhere.

His portrait looks down from every wall, even from trucks and tractors. His name is carved on the mountain sides, with letters tens of meters long. His birthplace – a two-story house in Gjirokastër – is a place of national pilgrimage.

A master of Stalinist self-preservation, Hoxha mercilessly liquidated all his opposition in the People’s Socialist Republic of Albania.

The revolutionary elite, convinced that human nature can be reshaped through continuous indoctrination, has set itself the goal of forging a new Albanian citizen who, without asking any questions, will be ready to make any sacrifice in the war of the homeland against the “wild imperialist-revisionist encirclement”, to build a socialist society freed from the heresies of individualism, independent thought or foreign morality.

As it struggles to remodel its citizens, this small country, once a backward country, has now made impressive strides towards development.

Take as an example the Metallurgical Plant in Elbasan, called “Steel of the Party”; the hydropower plant of Fierza called “Drita e Partysi”; the number of 700,000 students, compared to 56,000 in 1938; two radio stations in 1945, which in two decades went to 52; average life expectancy that has almost doubled in four decades, – are certainly significant achievements.

The regime is also trying to uproot the patriarchal clan structure, which has been the only social structure in the harsh Albanian highlands. He is eradicating blood feuds that, until 1920, were responsible for the death of one in four Albanian men. He suppressed the blood feud for adultery.

(Highlander tradition gave the husband the right to kill the adulterous wife and her lover. The woman’s family, in a ritual approval, sent the bride off with a bullet as a dowry.) The reformers banned marriages from the cradle, the sale of 12-year-old girls in marriage, and attacked the customs that shackled women, traditionally considered “long-haired and short-minded” to an inferior role.

No corner of Albanian life has escaped Enver Hoxha’s mania for control. People with “inappropriate or offensive” names, according to their political, ideological or moral views, are obliged to change them. Not even the dead have escaped Hoxha’s mania for reform. Burials, paid for by the state, take place in common cemeteries, without religious separation.

Turn back the shiny coin of the fight against illiteracy and you will see the dark side of the constant control of thought, because the Directorate of Agitation and Propaganda decides what books Albanians should read, just as it is the state that decides who should work where. who will be rewarded and who will be punished.

The vigilante society closes its doors

The merciless hand of history has imprinted in the minds of Albanians that they can move forward with great sacrifices. After three weeks in Albania, I realized how small I was to penetrate the strong wall of this social experiment.

Never in my travels around the world had I come across such a closed society that I felt like I was in a desert.

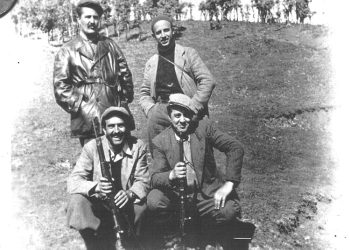

Accompanied and constantly checked, I felt that with the yellow car I was driving, I was seen as a rapid spreader of leprosy. My companion, Bashkim Babani, always stood behind me, to see what my camera would record.

It allowed me to photograph the outside of the industrial buildings, but not to observe them inside. I could not visit the hydropower plants either.

At a factory, they gave me brandy to drink, but I was not allowed to see how it was made. My requests to visit family and home were politically forbidden and were never considered. No pictures of bunkers, donkeys, certainly nothing primitive.

But the Union never stopped me from duplicating Albanian postcards. A citizen stopped at the entrance of the Puppet Theater in Tirana, remained focused on my camera. The union gave me all hope of photographing a wedding ceremony.

The government does not allow traditional celebrations to take place. I didn’t see any dogs or cats on the streets, symbols of bourgeois luxury. I once had a conversation in Turkish with a local.

Bashkimi immediately changed the conversation to Albanian and translated the answers in common party jargon. I couldn’t understand his defense. He was correct and friendly, as most Albanians are.

Only once did I have the opportunity to see the breaking of this habit, when on a farm near Shkodra, a teenager approached me, forcefully waving a slogan against foreigners in front of my face. I tried hard to give a more intimate flow to the conversation, telling the Union about my life in Istanbul with my wife and son.

But he never gave me the opportunity to form an idea of his private life and thoughts. Indeed, he seemed to have the mask that his entire nation proudly wore. Even the walls that he had built around him, I could not pass them. He was always correct and polite, just like most Albanians.

Only once did I encounter a crack in Albanian hospitality – when a young man picking grapes on a farm in Shkodër stood in front of me and shouted in my face an anti-foreigner slogan.

I tried to create a family atmosphere, telling the Union about my life in Istanbul, about my wife and son, but he, like Enver Hoxha from “Mercedes”, never lifted the curtain that separated us, to allow me even for a second, to see his personal thoughts.

It seemed that he had made that kind of attitude and that mask that his nation also wears on its face, in such a defiant way, completely a part of him. Memorie.al