By Eugjen Merlika

The first part

A life under dictatorship

(Memories of a “class enemy”)

MIXING Literary, Social, Historical, And Human.

“Here is the oil and the sadness

It is already felt among the leaders

This is where the sound is felt

Of my bars

The grief of a deserter

“The sea waves are falling.”

NDRE MJEDA

Memorie.al/ It seems to me a moral duty to myself and a necessary need to inform those who had the good fortune not to live the long decades of the Albanian monist system, to write a few pages from the history of my life, just to make it known some images from a reality, which conditioned many lives. It is a reality that today has been put on the edge of criticism by many people from different spheres of the cultural life of the Nation. Without pretending to be part of those spheres, I think I give a simple help in revealing some indisputable truths, directly experienced.

The very fact that I am writing these lines, forces me to begin them with a sincere reverence for all those factors and forces that made possible the arrival of these new days in which the truth, massacred so far, is revealed in it. all its breadth and depth. My special honor goes to the people of Shkodra, Kavaja, Tirana and other cities and, above all, to the students of the University of Tirana who, with courage to selflessness, fought for the democracy of today, making them a great service to our nation. I think that for this service, this nation should be grateful to you for the rest of your life.

During my life I have not kept a regular diary, as often happens to people. This happened not out of laziness or neglect, but simply out of a sense of self-preservation, which for decades was imposed on me by the conditions of an insecure life, with Damocles sword in his head (risk of arrest at any moment). This diary would have presented as a documentary many moments of a life crippled by dictatorship. Whereas today, at the age of 47, (I am a twin with the dictatorship that, ironically, is called “liberation”) I have to address only the memory faded by a multitude of factors…

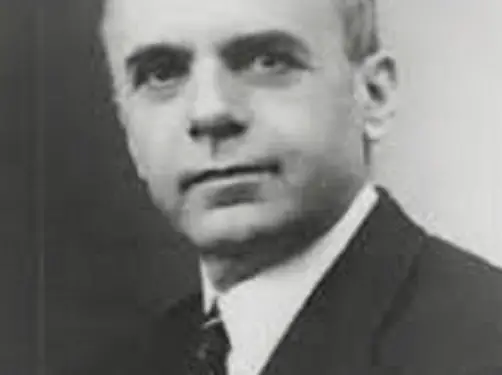

I was born in Tirana in April 1944, the son of a couple of intellectuals with high schools. The father was an electrical engineer, graduated in Grenoble, France, while the mother was a literature teacher, graduated with 30 with praise in one of the oldest universities in Europe, in Naples, Italy. This was a somewhat unusual fate for the stage of development of the Albanian society of that time. I have my life from God and from Dr. Hamdi Sulçebeu, who in no way refused to perform the failure proposed by the gynecologist when the mother was pregnant, responding: “I was taught at school to save them, not to kill the children.” But many times in my life I have been wondering if I should be grateful for his gift…

In the clinic of Dr. Sadedin, where my mother was hospitalized, was also sheltered by partisans or guerrillas in Tirana. The German checks were preceded by the expression “I have a new patient of Mustafa Kruja” and calm in the clinic was ensured. Perhaps this was a distant signal, the forerunner of pluralism that would come after almost half a century, or perhaps it was a subtle calculation of the chances of survival at a time, that would come in the name of the socialist revolution. I later learned these details from my mother, whose life is a novel in itself, of tragic proportions, worthy of a Dostoevsky pen, the description of which I do not feel capable of. The testimonies of the friends of that half-century-old ordeal that have been spread everywhere today, in Albania and in the world, would be enough to fill that novel.

The first incident, strangely ingrained in my memory (I was three years old and I do not know if such a fact is scientifically accepted), was the crawling on the bars of the Tirana prison gate with the words: “Dad, come with us” that I pronounced tearful and with perseverance not to be separated from the father within her. There was my first acquaintance with the absurdity, which did not allow me to embrace my father, as well as the first meeting with the police, the cause of this stop, a figure who only changed faces and accompanied me throughout the course of the river of my life. “This is your life Faust! And he calls this my life … “Goethe

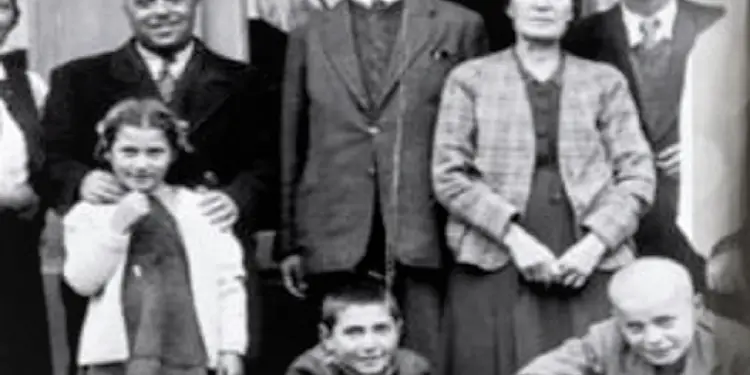

The first conscious confrontation with life took place through the arrests of father and uncle. I was left alone with my young grandmother and mother, then 26 years old. We lived in new Tirana, in a rented house, because our house was occupied by Spiro Moisiu, the chief of staff of the “national liberation” army; still today I am not given the right to live in it … One fine day in 1947, came the order to move from Tirana to Shijak. In the same building where we lived there was also a Yugoslav girl named Nada. He was a colonel, but I do not know what function he had. He spoke French with his mother and they were also friends by music. Her mother played the piano, sang many Italian songs and arias from operas that she liked very much. Our relocation order disappointed Nada. He tried to cancel it by all means, he himself intervened to the interior minister, but the answer was negative: “I cannot do anything for that family alone.”

So that same day we were in the hut of an evjit, in the four streets of Shijak, me my grandmother and mother. The father had begun his long odyssey, in labor camps. He was sentenced to fifteen years in prison for attending a rally with few friends to legally form an opposition party at a time when they were “officially allowed” by “popular democracy”.

I do not have special memories from the hut of Shijak, but after almost a year my father’s uncles took us to Kruja, our city of origin. I turned five there. Because of my zeal and desire to learn, a good teacher enrolled me in the first grade. But the decision taken by the Ministry of Interior, together with the Kruja branch (perhaps somewhat delayed, because the other families had been in internment camps for years) was implemented and we were forced to live for several months in the cells of Kruja branch.

The beautiful and human figure of my first teacher, who used me and brought me from school to prison, appeared in the fog, while every morning the police opened the gate at the same hour, to allow me to go to school. I am very sorry that I do not remember the name of that girl and I do not know if she lives … But I am very grateful to her, not only that she taught me the first letters, but that with her motherly care and compassion she became me very close. I do not know if she paid the price for her humanity, because the harsh waters of the class war did not allow such a benevolent attitude towards a child of “enemies”. To me it was like a ray of light in the long tunnel through which my life would pass, an example that showed me that there are good people in life, which I would prove time and time again in the years that followed.

There, in the cells of the Kruja section, along with two other families, there was a Greek, a monarchist, who came here as a result of the war. He looked at the cups of coffee. One day he saw his grandmother with the cup and said these words: “From here you will leave soon. You will go far, you will cross mountains, plains and rivers and you will stay in a place between mountains.. There you will suffer a lot, a lot and after a few years you will return again from that road, but not here anymore. You will be standing in the middle of the road in a field. There your life will improve, but as good as you have been, you will never, ever become …”Those women and girls who heard him laughed and said that fortune-telling is unknown, but the Greek was Kalkanti. His fortune was proved with astonishing accuracy…

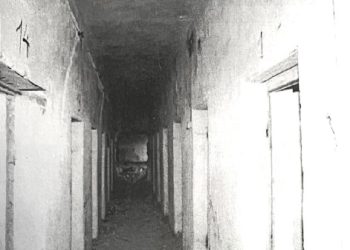

One day in November 1949, they put us in a truck and set off on a long, long road that crossed plains, rivers, and mountains and ended in Tepelena. Tepelena … famous in Albanian history as the place where the activity of one of the most complex and controversial personalities of the Albanian Nation began, Ali Pasha, the Vizier of Ioannina, would become, in the second half of the twentieth century, the most symbol alive and most terrifying of horror, that only Albanian Stalinism could invent. Tepelena, officially the Deportation Camp, in fact that of the extermination of the people, was undoubtedly equated with Mathausen, Auschwitz, Buchenwald. It is true that they did not have their crematoria, but forced labor, lack of food, and the cruelty of the police apparatus made death more desirable every day than life. Death hung over our camp, it had its prey almost every day, among a diverse crowd of Albanians, of all ages and from all provinces, housed in five large military barracks with hundreds of people each.

Tepelena and other labor camps were the open cemeteries on the body of Albania, the strongest, most shocking and incomparable evidence of the dictatorship of Albanian communism of Enver Hoxha, Mehmet Shehu, etc. Tepelena is an indelible stain of shame on the consciousness of the Nation. It is a special task of the Albanian democracy, to remember with a magnificent monument the innocent victims of that great tragedy. It is also a task of free Albanian literature to give the world an Albanian-branded Gulag Archipelago. Tepelena has so many subjects from the memories of the people, that a powerful feather (I believe that democracy will bring them out) would create a major work of world proportions. The spiritual and life tragedies that took place in that camp are innumerable.

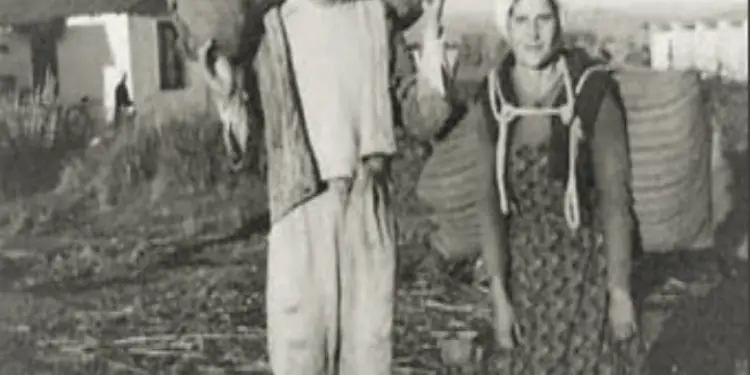

The day at camp began with the night, at three o’clock in the morning. The illiterate policemen started reading the internees one by one at that hour and finished it at five o’clock. Then began the morning meal, boiled water called tea. Then the long line of women, men, and young people left for the mountains, to meet the norm of wood – cutting and loading on the ridge, under the surveillance of police officers with rifles in hand. They would supply the army with wood, the cooking camp, the heating command, the internal affairs branch, the families of officers and policemen, the members of the party committee and the executive committee … People had returned to the role of mule, the episodes of the pains of this work reach such sharp peaks, that they would offend the conscience of every being called man.

I remember on New Year’s Eve 1951, together with my grandmother, we waited for my mother to return from the mountain. Grandma had cooked something, like porridge with a little flour that we would eat to “celebrate” the New Year. My mother returned with three of her friends, daughters of well-known anti-communist political exponents, the so-called “traitors”. After they all returned to the camp, the policeman loaded them again with wood and sent them to the city, to bring wood to the house of a police officer. Near midnight they returned to the barracks. What a beautiful new year, while others, “pets of luck” celebrated with all the best in the Hotel “Dajti” or in the Palace of Brigades …

That animal work was met with a food, consisting of six hundred grams of bread, oatmeal with worms floating in its juice, supplemented by wild cabbage, squash, oak stuff, gorricas, these when we could find them outside camp. If you add to this picture the terrible hygienic conditions, the lack of sufficient bathrooms, buildings, sleeping place (total thirty cm. Width per person and twenty for children), to create the real picture of daily torture in that accursed place, which was called the Deportation Camp.

There, at the age of six, I became acquainted with the cell or “dungeon”, as it is commonly used. One day, playing as a child, I committed a great “pity”. I had stoned command pigs grazing quietly in freedom, outside the barbed wire of the camp. The policeman had seen me. He approached me, grabbed me by the rags and put me in the dungeon. I still shudder at the memory of those hours spent in the darkness of the dungeon, alone, weeping for fear of the gogol. My good grandmother used to talk to me outside: “Do not be afraid, my grandmother strangles the gogol!”. She also resisted the police who threatened to remove her. At two o’clock at night another policeman opened the door of my dungeon and I regained my “freedom”.

Such facts may seem a little unbelievable, but the truth is that there were other such cases, in addition to the hundreds that constituted the cruel law inside. One of them, which comes to mind now, is that of a sick woman who groaned from kidney pain and “disturbed the peace” of the policeman who, consequently, tied her to a pole for twenty-four hours. After that she barely came to her senses for ten days. I believe that the cynicism and sadism of the command staff surpassed many of the essay figures we saw years ago in our films or in other Eastern countries.

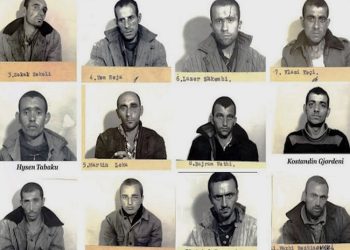

Humiliation and torture were the greatest pleasures felt by these former partisans in their dealings with internees of any age, innocent people whose only crime was that they belonged to the families of fugitives or opponents of the red dictatorship. The names of Lieutenant Haki, aspirant Syrjai, captains Selfo and Tomi, policeman Ismail and many others are images of human evil in the minds of former camp residents and are still remembered after forty years, when life has erased from memory the names of heads of state you govern.

Young women and girls coming from the mountain in the rain in wet clothes up to the flesh, wearing no underwear (at the time of internment they were not allowed to take anything but body clothes), were forced to cover themselves naked under blankets, after the clothes squeezed and left to dry. The “vigilant” guardian of the “most advanced order of humanity”, when he spotted such a thing, would go and pull the blanket, leaving the “enemy” Albanian exposed in the painful eyes of those present. From which enemy over the centuries would the Albanian expect such a nation? Where to look for comparisons? Perhaps in the stories of Kuwaitis raped by Saddam Hussein’s supporters.

Forced labor, hunger, and suffering had turned thousands of people into living skeletons. Above the sick children, the death scorpion danced daily, ready to take its share. In a labor camp, a prisoner, when told that his brother had died, asked if he had received the ration of bread for that day …. Such episodes also occurred in the Tepelena camp.

Another chapter in itself, terrifying was that of children. The young children, whom the young mothers were forced to leave tied up in the cradle all day, grew up at the mercy of a foreign old woman. It happened that after unloading the burden of the trees, at night, the young woman found her creature resting in eternal peace, with an angelic appearance … Tears and curses were too little to express the pain; the next morning, he was waiting in line with his friends for the mountain…

The children who were left alone grew up at the mercy of relatives and sometimes even strangers, because the mothers were taken to labor camps, to build “works of socialism” for free. I remember that bitter day when I was separated from my mother. I was trying to crawl into the truck while the police hit my hands. Tears flowed from the eyes of those generous highland women who had volunteered to replace my mother in this transfer, but the order was final: she had to be separated from me. The policeman had to carry out this order of his superiors, hitting the hands of the child who did not want to be separated from the mother … What a beautiful scene for a painting worthy of the Mouth, a beautiful subject to illustrate “socialist humanism”, trumpeted diligently in this half-century.

The “class war” was systematic and with the dead. The location of the graves was changed three times, until they took him to the edge of the Vjosa, so that his bones could be swallowed by the river, after she shortened their life, the famous “demarcation line”, “the touchstone for the Albanian Marxists-Leninists”. Even today, someone calls these monsters justified and even useful, justifying them with the “cold war”, with the saboteurs. I am reminded of Hamlet’s character, in conversation with his mother, when he says: “I will put a mirror where I can see the blackness of your heart …”. It is the duty of every free man to present this mirror to the “glorious” strategists of that war, who embodied in himself everything that was Mephistopheles in human nature, the dark corners of which the colossus Dostoevsky had known so well, predicting even danger, a hundred years ago.

Two years of school in the city of Tepelena. Only students were allowed to go outside the barbed wire fence to continue their seven-year schooling. Compulsory education alone did not make a difference, everyone could get it. Scenes of going and coming back from school come to mind. A Mirdita girl, Bardha, was holding my hand. She was older than me, older, even though we were in the same class. She was the cousin of Pal Mëlyshi, whose family we had face to face in the first barracks. We all learned, the children of the camp; though hungry and naked, we were the best in lessons. What was the power that gave us wings to face that hell every day? What major forces were put in place to ensure our survival? “Great God help us!”, This was the sigh from the depths of the soul, by itself in every moment of pain and weakness …

After two years in the Tepelena camp, the order came that the children should be released from exile. Whoever had free relatives went to them. I was left alone with my grandmother, until my father’s uncle, a well-known pediatrician in Korça, took me to his house. He and his wife became second parents to me, they treated me with great love and compassion, they took care of my fate all the time, and they tried in every way to fix my little started life. But the wound in my soul was very deep. The material conditions of my life were like day and night with the past, but the absence of parents is not filled with anything, even though I found second parents that I loved wholeheartedly. My mind went beyond the barbed wire, where grandma, mom and dad stood separately. Insecurity, anxiety about their lives, longing, and pain made me secretly shed bitter tears. Those tears of eight-year-old children, like thousands of children all over Albania, were pearls that “adorned” the crowns of the world’s powerful. But at that young age we children did not understand things, whereas today they do not have our naivete then.

Our parents at that time did not talk in our eyes about their situation and the country, or political problems. Terror had penetrated to the cells and no one dared to tell the truth. So we were molded with the “endless” love for the Party, Uncle Enver, above all for Uncle Stalin. These illusions, introduced to us by the school, contradicted our treatment in life, but we were unable to think with our head. I remember an episode as funny as it was painful. I had gone to meet my mother who was in camp no. 3 at the Brick Factory in Tirana. It was the summer of 1953. Mother and her friends were working on brick fireplaces inside the camp wires. The officer allowed me to stay two days inside the camp. In conversation with the women and girls who lived in a room with their mother (there could be about twenty of them) I asked them without hesitation if they had cried when Stalin died. They started laughing and said that the only good thing they got was that they had two days off. Indoctrinated by school and life outside, I replied angrily: “They do well to keep you inside.” They exploded back into gas. They had the right to laugh at me, that I had forgotten Tepelena and did not understand the real perpetrators of the tragedy. Compared to today’s children, who raise two fingers upwards, we must admit that we have been very credulous, not to mention foolish, and perhaps that explains the longevity of Stalinist dogmas for decades.

But I want to go back to Tepelena, a nail embedded deep in the conscience, heart and brain of many of my mid-twentieth-century compatriots. The strategy of physical extermination was associated with another, even more diabolical, that of human decay, for which various means and means were not spared. In extremely difficult physical, moral and psychological conditions, the vast majority of that community kept their foreheads high did not blacken the face, maintained dignity, character, respect and love for each other. In large barracks, with two rows of beds, over five hundred people slept, and to the surprise of the “bright architects” of that human vileness, no moral scandal occurred. They were all called brothers and sisters and remained in each other’s memories, challenging the dictatorship and its cruel laws. Without any help, those people between whom I lived for two years, endured those long years until 1953, as a result of “open skies” and the pressure of outside opinion, the Government decided to close the infamous Tepelena camp./Memorie.al

The next issue follows