By Bashkim Trenova

Part twenty-seven

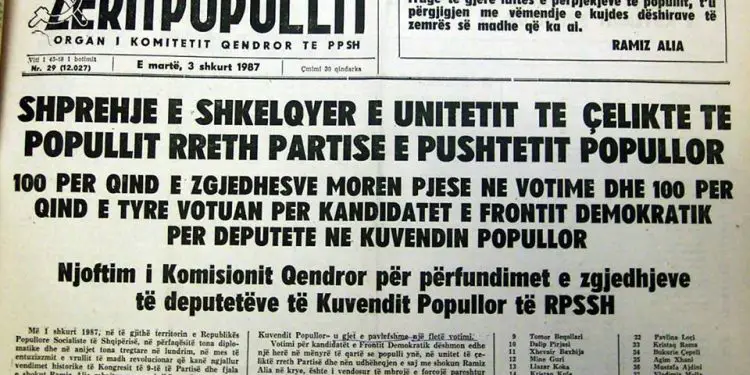

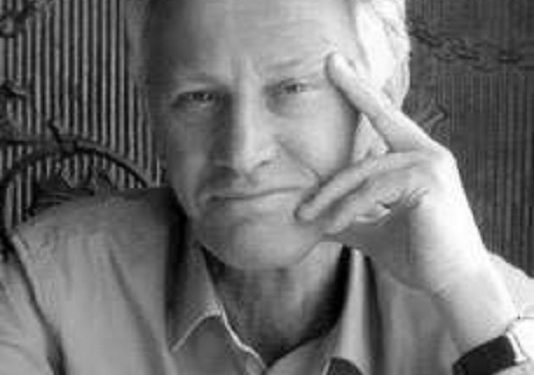

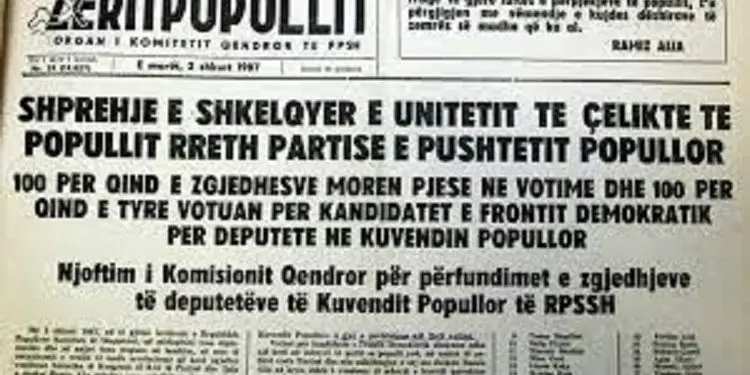

Memorie.al publishes the memoirs of the well-known journalist, publicist, translator, researcher, writer, playwright and diplomat, Bashkim Trenova, who after graduating from the Faculty of History and Philology of the State University of Tirana, in 1966 was appointed a journalist at Radio Tirana in its Foreign Directorate, where he worked until 1975, when he was appointed journalist and head of the foreign editorial office of the newspaper ‘Zeri i Popullit’, a body of the Central Committee of the ALP. In the years 1984-1990, he served as chairman of the Publishing Branch in the General Directorate of State Archives and after the first free elections in Albania, in March 1991, he was appointed to the newspaper ‘Rilindja Demokratike’, initially as deputy / editor-in-chief and then its editor-in-chief, until 1994, when he was appointed to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs with the position of Press Director and spokesperson of that ministry. In 1997, Trenova was appointed Ambassador of Albania to the Kingdom of Belgium and to the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Unknown memories of Mr. Trenova, starting from the war period, his childhood, college years, professional career as a journalist and researcher at Radio Tirana, the newspaper ‘Zeri i Popullit’ and the Central State Archive, where he served until the fall of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, a period of time when he in different circumstances met many of his colleagues, suckers of some of the ‘reactionary families’, etc., whom he described with a rare skill in a book of memoirs published in 2012, entitled ‘Enemies of the people’ and now brings them to the readers of Memorie.al

Continued from the previous issue

“Enemies of the people”

Spahiu and Xhezo, the two strong pens of “Zeri…” against the bureaucracy!

Xhevair Spahiu was not only a talented poet, but also a talented journalist. As a friend and colleague of his expressed in a recent interview in “Zeri i Popullit”: “Xhevair Spahiu, as the Party said, hit the bureaucrats in the head with his flaming articles”. For me, Xhevairi as well as Arshin Xhezo, another journalist of “Voice of the People”, were two strong pens, playing the role of prosecutors in the press of the Labor Party. “Feet in a shoe to those who taste about the troubles of the people”, was e.g. the title of a sensational article written by Xhevair Spahiu. In this article, party and state cadres were put in a red circle. At first glance it seems that the “flame” articles of Xhevair and Arshin hit the bureaucracy and bureaucrats like an earthquake, but the bureaucracy and bureaucrats were in the Party, they were its offspring. The Party itself was deeply bureaucratic. In Albania, the “fight” against bureaucracy was led by the bureaucrats themselves. The items against them were fireworks. The fire of hell had its hearth elsewhere, in the Central Committee of the Party. No article, to address this subject, even indirectly, with implication, has been published by anyone.

It is understood that Xhevair’s critical articles also made him quite dissatisfied, who probably even waited for the opportunity to take revenge. However, he was not hit even for his work as a journalist. After all, it must be said that in the journalism of the dictatorship, for such topics, the glory and the end of the journalist depended entirely on the word, on the judgment of the dictator. It was he who used the newspaper “Zeri i Popullit” as a weapon to undertake the constant hunting of witches, to have under control and terror the Party cadres throughout its pyramid as well as the Party itself and the Albanian society. In this view, the journalists of the “Voice of the People”, to one extent or another were a direct echo of the dictator’s spirit, his dictatorial interests, his combinations and clan intrigues, despite the fact that they could even think honestly. That they served the high interests of the country or the people. This, in my opinion, also explains the fact that the dictatorship puppets trembled from the articles of the “Voice of the People” journalists, but at the same time felt powerless to take revenge.

Xhevahir Spahiu’s ordinary joke with the brandy that cost him dearly!

Xhevairi would suffer severely only from an ordinary joke in the conditions of democracy, but sacrilege in the conditions of the dictatorship where no jokes were made even with jokes. In the summer of 1977, a meeting of the People’s Voice Party was held. It said that when Xhavair Spahiu had been to Përmet, he had been friends with Arziko Ismaili, former secretary of the Përmet District Party Committee, sentenced to 10 years in prison for hostile activities. After the arrest of Arziko Ismaili, in her house, during the police control, a material was found, which was about a “symposium on brandy”. It proposed topics for discussion such as: “What did the classics of Marxism-Leninism say about rakia”, “The struggle against bourgeois ideology, which underestimates the role of rakia in the revolution”, “Rakia and the future of humanity ”,“ The architecture of rakia clubs ”, etc., in the same style. Arziko Ismaili, when asked in the investigator or in court, said that this material was prepared by Xhevair Spahiu, in her office, when she was the party secretary. This joke or this humor of Xhevair was found as a mockery of the official Marxist-Leninist ideology, with the revolution, as a conclusion with the Labor Party, and consequently with the dictator. Xhevair probably did not even think of such things when he received the pencil and paper in Arziko’s office. If he had thought of them, most of what he would have done would have been enough to recite them and not to throw them on paper, which he did not even tear at the end, but left willingly as proof, as evidence against himself !

In the organization of the “Voice of the People” Party, as far as I remember, there were critical thoughts, strong, but also more moderate. In general, the “Voice of the People” was established as a kind of tradition; journalists were protected in the organization as much as the organization could do this protection. I was at that time a member of the bureau of the Party organization. In the bureau of the Party we were served ready from above, as it was said then, the decision to sentence Xhevair Spahiu. The discussion in the organization would be formal, just to say that democracy was respected in the Party and to leave on the backs of Xhevair’s colleagues, the newspaper communists, and the decision that had been made elsewhere for him.

Xhevair Spahiu took four punitive measures, thus paying a very high price for Përmet’s “glass of brandy”. The organization “decided” to expel him from the Party, to leave “Zeri i Popullit”, to be deported to Puka as a family, to be sent to the mine to be educated among the working class. I remember the sentence was later commuted. Xhevairi, for example, left “Zeri i Popullit”, but not from Tirana. Who helped him this time too? There is plenty of speculation about this. Xhevairi himself, as far as I know, never spoke about the sentence given to him and the years that followed. It seems to me that Xhevairi is not a unique case. It is not that we notice only in his case the fact of severe punishment in the organization of the Party of the institution and, subsequently, the relief of this punishment by those themselves, who forced the organization to position itself harshly. Such low games were made in order for the convict to be grateful to the leadership of the Party and the dictator for the generosity shown, thus to serve him as a debtor even more faithfully, but also to keep alive the spirit of distrust and disunity between people, friends and colleagues. Thus the dictator and the Party found it easier to rule and make the law.

It is interesting that after all this, in 1979; Xhevair Spahiu managed to publish a volume of poetry entitled “Awakening of the depths”. Today anyone can publish. It was not like that in dictatorship. There was then only one State Publishing Company. Everything was controlled, the author and the work. From this point of view, Xhevairi is probably the only writer or poet who, in terms of his sentence, manages to publish. “Awakening of the Depths” came out and lived only two or three days in two or three bookstores. Very quickly, always custom-made from above, it was withdrawn from circulation and sent to become cardboard. As far as I heard, after that he was deprived of the right to publish and other punitive measures were taken. Nevertheless, we see that in the following years, in 1980, 1981, 1983, 1987, 1989, 1990, 1991, he again publishes.

Even after the overthrow of the dictatorship, Xhevairi continues to create, always with the same style, sometimes, sometimes desperate, sometimes, sometimes revolting, always with the “worries of the people”. He was elected for several years President of the League of Writers and Artists of Albania. Now he holds the academic title and in the Albanian press, especially at the time when he was going through a serious illness, he was described as a “great poet” or “great writer”.

The beating and punishment of the literary editor of “Zeri …”, Niko Tanini!

In “Zeri i Popullit”, over the years, not only journalists, heads of departments and deputy editors-in-chief have been hit, but also editors-in-chief, even ordinary employees, who had no direct connection with journalism as creativity. The most shocking case for all of us who worked at this newspaper in those years is definitely that of its literary editor, Niko Tanini. In my life I had seen many colleagues and friends expelled from the Party, penetrated into remote regions of the country, between the mountains where neither the sun rose nor the sun set, imprisoned in cells to die there. I had not seen anyone handcuffed as he crossed the threshold of the office to go home, to rest somewhat, to drink a glass of water, to pet the only child once again, perhaps for the last time. Something similar happened to Niko Tanini.

At a routine critique meeting of the week, our editor-in-chief pointed the finger at Niko, adding that “we have enemies among us”! Niko faded and someone, it seems to me, Petrit Çani, an old journalist of “Voice of the People”, offered him a glass of water. We were all left speechless. None of us could think of Niko Tanini as an “enemy” of power, dangerous for power and revolution! I am convinced that even the editor-in-chief, Agim Popa, did not believe the words he said. He was not one of those who discovered and denounced “enemies”. Agim Popa, like everyone in his post, was obliged to pass on to our collective what the organs of the dictatorship of the proletariat had served him.

Agim Popa had been a partisan. A brother had a martyr. The whole family was affiliated with the Antifascist Movement. In 1959, he served in Tirana as the dictator’s translator in his meetings with Khrushchev, the leader of the Soviet Communist Party, as well as later in the Kremlin Meeting of Communist Parties. He had performed the same service for Prime Minister Mehmet Shehu in a Session of the United Nations General Assembly. He was, therefore, a trusted man of the regime and had always held important positions in the ideological and foreign relations sectors. Nevertheless, he too had a shadow, which followed him all his life. At the Tirana Party Conference, held in 1956, in the general atmosphere that was created there, to the numerous criticisms of the cult of the individual and the privileges of the senior leaders of the Labor Party, a question of Agim Popa was added. He asked to know: “What are the reasons for the sentencing of Tuk Jakova and Bedri Spahiu?”, Two former members of the Politburo of the Labor Party imprisoned as “enemies and traitors”. Tuk Jakova was also the ‘People’s Hero’.

Dawn had sought reasons where she had never existed. This was his mistake, noted in the blocks of Mihal Bisha, the Director of Staff at the Central Committee. From this Conference and its consequences, Agimi had thus learned that reason should not be sought where it was not found, that questions should not be asked about the decisions taken above, that he, like every member of the Labor Party, was no more than , as it was said at the time, “Party soldier”. The soldier is only required to blindly carry out the commands and not to discuss them, but to give his life for their execution. This was also called “Party discipline”. This role was played by Agim Popa in the routine criticism of the week when he addressed Niko Tanini. I felt very sorry for Nikon, but also for Agim Popa, for whom I always had and maintained the same respect. Niko was accused because somewhere he told someone that there is no democracy in Albania. To whom and where, we should neither know nor ask. We just had to judge, throw Nikon away like a torn cloth, for an anonymous fact, unknown to us, unheard and unexplained.

Niko Tanini was approaching retirement. He had a whole life working in “Zeri i Popullit”, bent over the writings of journalists, who did not always write correctly in Albanian and who did not always agree with his interventions. Niko’s portrait was given quite well by Mehmet Elezi, journalist and later editor-in-chief of “Zeri të Popullit”. In an article published in 2003 in the Albanian press, after Niko’s death, Mehmet Elezi wrote: like all idealists. When a well-known professor or academic came to the newsroom, he was happy and wore his glasses. More than anyone else, he enjoyed associating with linguistic professors and historians. Perhaps this tendency expressed a long-standing desire or dream to pursue science. “I was happy to get involved in the debates and show my knowledge.”

Niko was an open man, a sensitive man. He used to come to my office sometimes. He wanted to read the Newsletter of the Albanian Telegraphic Agency, that part of the bulletin, which was not published, but which was given only to us of the Foreign Sector for information and to use it in our comments and political notes. He never uttered a word to offend anyone. He never commented, as a secret “enemy” that was, even indirectly, the news he read about world developments, that he read in my office. If he had something to say he did not hide it, he said it openly, in front of everyone, but always without malice, even with humor. Irony, too, was not lacking.

In the editorial office of “Zeri të Popullit” it had become a similar tradition that when someone left the newspaper and was appointed to another position, more responsibly, a meeting was organized with all the employees of the newspaper. In these cases we were also offered a glass of cognac. We wished “good job” and “success” to our departing colleague. There were also jokes and hilarious stories. At such a meeting, Niko Tanini, after drinking somehow, made portraits of several journalists. As far as I remember, someone asked him if he was crazy about Pavlo Gjidede, a well-known journalist of “Zeri të Popullit”. After some thought, Niko sketched it out with these words: “Pavlloja?”Hmm, a failed saint.” Then someone asked him about Petrit Çani. Niko glanced over from Petrit and said: “Petrit, eh?”Come out a little so I can see his face.” Niko issued such jokes that day about Mehmet Elez, Thimi Nika, this journalist in “Zeri i Popullit”, Shaban Hidri, secretary of the Collegium, and others. We all laughed at his words. No one was offended.

Otherwise, Niko left us quite differently. Instead of the noise of humor, an anxious silence. Instead of the cheerful knock of the glasses of cognac, the crackling of the handcuffs, which they put in their hands, just went down the stairs of the “Voice of the People” building. There, he was met by two State Security agents, who put him in a “Jeep”, without leaving him time to turn his head from the house. He lived on the other side of Stalin Boulevard, in front of the People’s Voice building.

Niko was sentenced, if I am not mistaken, to 10 years, on the basis of the infamous article “for agitation and propaganda” against the popular power. In the courtroom, as we were told in the newsroom, he “was brave” and declared: “There is no democracy in Albania!” I do not know if this is true or it was said to aggravate it, to prove what was not proven in the collective when he would be arrested, so that Niko was an “enemy” and we should be calm in our conscience. He was released from prison with the start of the Democratic Movement. Noble, he never caught the mouth of his whistleblowers, the timed witnesses who slammed him into prisons, investigators, guards.

Already old, he had only one mortgage. He wanted to leave Albania for Canada where his only daughter, Jenny, lived, to live even a few days with the one who left him a child and found him an adult, a woman. Niko also took out her passport to Canada, but it never worked for her. He did not have to pay for the plane ticket. He expected Democratic and Socialist governments, which alternated, not to give him the same compensation for his years in prison. They had promised this to the former political prisoners of the dictatorship, but only promised. Niko did not ask for much for ten years in prison. He wanted so much to pay for the plane ticket. This would be the only “reward” for years in prison. Would not like it if there was another funding option. The girl did not want to be paid for the ticket. He was quite proud and knew that in emigration life is not rosy, as is often believed.

Niko could not go to Canada, he no longer saw his daughter and nephew, who was the same age as his daughter Jenny, when he was imprisoned. He had wanted to educate her with patriotism. They had met once and he had recited the verses of our Renaissance poet, Çajupi: “Where do we find clay sweeter than honey? In Albania”. Niko Tanini was covered in this mud. He had many benevolent friends who respected him, but after prison he lived alone and also left this life, alone, like the day he was handcuffed, but now never to return. After prison I met him only once. He came and greeted me in the editorial office of the newspaper “Rilindja Demokratike”, which at that time had its headquarters not far from his house. We never met again and I feel a hostage. Life grips us in its daily vortex and we forget that we are not eternal, that a meeting can be the last even when we do not want it.

After Niko Tanini, “turn” to the dock, for Pipi Mitrojorgji!

After Nikos, Pipi Mitrojorgji, the newspaper’s editor-in-chief, would be put on the bench of accusation and overwhelming criticism. In its history, the newspaper “Zeri i Popullit” counts some editors-in-chief, who have been declared “enemies” and “traitors”. Such are, for example, Fadil Paçrami, Dashnor Mamaqi and Todi Lubonja, all three members of the Central Committee of the Party, all three interned and imprisoned by the dictatorship after the IV Plenum of the Central Committee of the Party. Would the Party reserve this tragic end to Pippi Mitrojorgji?

When Todi Lubonja was convicted, he was sent by the Central Committee of the Party, in a meeting with the journalists of Radio-Television, Pipi Mitrojorgji. At that time he was the director of the Press Directorate in the Central Committee of the Party. Among other things, Pipi told them: “Work carefully and vigilantly to eliminate as soon as possible the traces of the hostile work of Todi Lubonja on the Albanian Radio Television”. A few years later, he had to answer himself in front of the journalists of “Voice of the People”, about another “hostile activity”, in which he, whether he wanted to or not, would be mixed. This is the whole history of the Albanian Labor Party. Today’s accusers have been returned to the next day by other accusers, who, too, will not be able to escape the fate of returning to the accused.

The history of this Party resembles a fatal dance during which those who are at the top pull others towards the end, while those who are afterwards push the former towards the same end. The tragedy is that everyone has been friends, warriors and heroes, hardened and scarred heroes. The irony is that some do it diligently because they are naive idealists, others, with the same zeal, do it because they are careerists, without personality. Some even do it out of fear. The latter are scared, they are aware that their dance is the dance of death, but they cannot get away from it, they hope that it lasts as long as possible, that it turns out to be like a crazy dream. Of course, in life and in man, divisions cannot be as sharp as with a knife. However, Pipi Mitrojorgji, as far as I know, I would rank among the naive idealists. Memorie.al

The next issue follows