Reflections on the Book by Dr. Sali Hidri, Dedicated to a Master of Albanian Letters

Memorie.al / More than a mere coincidence, I would call it a stroke of luck for the city of Durrës that the husband-and-wife team, Hava and Sali Hidri, with the dedication of true scholars, research, write, and encourage one another. Together, they collaborate to publish books of immense archaeological and historical value, compelling us to honor and appreciate their precious contribution. The themes and figures they address – with professional competence, culture, human warmth, and a profound love for the fatherland – constitute an indisputable contribution to their respective fields. Anyone who has closely followed their creative output has noted that an unerring intuition guides them, knowing exactly where to look and what to choose.

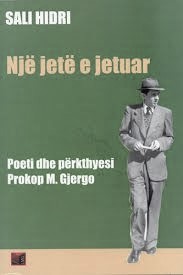

This is the reason why Dr. Sali Hidri must be commended for his monographic book, “A Life Lived” (Një jetë e jetuar), dedicated to a distinguished yet humble and wise intellectual, the model translator and soulful poet, Prokop Gjergo. The history of Albania during the dark years of communist obscurantism is filled with painful examples of the anathema, contempt, persecution, and even imprisonment or execution of many talented writers with European visions. The damage this cruelty has inflicted upon our Fatherland is incalculable.

But there is one thing the inquisitors often forget: a man may die physically, but his work remains. It is indifferent to ideologies, politics, the thirst for glory, or the careerism of anyone – be they Nero himself. The Frenchman Jacques Prévert, whom some have called “The most beloved among poets,” wrote in his poem “The Great Man”: “At a marble cutter’s where I saw him one day, he was taking the measurements for his successors.”

Such was our Prokop: an honest economist – a profession that shared nothing with literature – who yet found the time to masterfully translate such luminaries as Corneille, Racine, France, Beaumarchais, Boileau, Rostand, Molière, Hugo, and others. He did so despite being fully aware that in his country, most of these works would never see the light of publication as long as the three-headed Cerberus stood guard over the Albanian realm of Hades.

Prokop, as is clearly depicted in this book, loved life dearly. This was why, even under unfavorable conditions, he never ceased working. For him, this was more important than anything else. He knew well what Charles Baudelaire had written in “Joyful Death” (La Mort joyeuse): “Graves and testaments I have always hated; I want no tears from the world for me. I would rather, while alive, leave to the crows the chance to tear apart my worthless body.”

Yet, it was not only Prokop’s body but also his soul that was being torn by indifference. The author Sali Hidri illustrates this beautifully: “It was very saddening when, while recording the translated works in the presence of Mrs. Marie, I found – tucked under the cover of the typed and bound tragedy ‘Phèdre’ – a rhymed note in four verses dated November 11, 1977:

“Yes, dear friend, I know it well;

A day will come when this Albania

Will boast of these translations of mine;

But when?… Oh, when… after I am gone!”

The reader naturally asks: why did he leave this note specifically within this tragedy? What does it matter, after all, if Phèdre herself, out of remorse for her slander, takes her own life, when – following Theseus’s curse – the monster sent by Poseidon would terrify Hippolytus’s horses, leading the innocent youth to his death? But the field of creativity possesses something mysterious, something almost divine that often pays no heed to danger.

Dr. Sali Hidri knew Prokop very little, if at all. Perhaps Prokop’s nature was simply like that. I say this because even I, despite organizing countless activities for literature and culture with my colleagues, never met him. I knew he was the translator of those few published books like “Andromaque,” “Le Cid,” “The School for Wives,” “The Misanthrope,” etc., but he himself appeared in my mind as an invisible yet ever-present ghost.

In this light, I judge the effort required to write his monograph so convincingly to be a monumental task. Sali is now a man of great experience. Thus, he found the way to present us with a complete work about this man who – as the newspaper “Adriatiku” wrote in early 1992 – “…deserved a place of honor in the pantheon of our letters.”

If one examines the book carefully, they will notice that the author only touches briefly upon Prokop’s work as an accountant. Nevertheless, he has managed to let that professional life accompany us to the end of our reading without banally encroaching upon his essence as a man of letters. As the esteemed Dr. Ali Sula defined it: “In his translations, through his love and adoration for the art of the Greats, he gave everything he could to maintain the ideological fidelity of the text, the beauty of sound, the original cadence, youthful agility, elegance of style, and the purity and richness of the lexicon in the Albanian rendering.”

It must be kept in mind that Prokop translated works with strict metric rules; therefore, to an extent, they are also his own creations. The Alexandrine verse he employed has rigorous demands. Introduced into French literature eight centuries ago after the publication of the poem “The Romance of Alexander,” it found wide usage despite the fact that its twelve syllables require a caesura and accents on the sixth and twelfth syllables.

But Prokop Gjergo not only possessed a deep knowledge of literary theory; he had also written two books of poetry. His human side is exquisitely sculpted for the reader by the author. Now, no one can say they never knew him.

In carving this portrait, I find it of great value that Sali Hidri did not settle only for the memories of Prokop’s wife, nor for fragments of his original poetry or his masterful translations. Within the pages of this book, he has woven the correspondence Prokop maintained with cultural figures such as the renowned director Sokrat Mio or the lawyer Kristaq Harizi.

How soulful, friendly, and benevolent their letters are! What preoccupation, desire, culture, and sincerity one finds within them! Here is how Sokrat Mio wrote to him from Korça, as the vision of Paris rose before his eyes:

“Rereading them after more than 40 years was as if from the bottom of the sea – covered by a heavy past of events – memories emerged one after another, fresh, beautiful, and perhaps more attractive than they were in reality when I lived them; surely their absence makes those moments even dearer.”

In the souls of these great intellectuals, upon reading Gjergo’s miraculous translations, exactly what Baudelaire says in his poem “Parisian Dream” (Rêve parisien) occurs:

“This terrible and rare landscape,

Which no human eye has ever seen,

This morning, with its distant image,

Is making me a dreamer.”

And what lessons there are for any of us when we evaluate, encourage, or criticize someone. “Allow me, dear Prokop,” says one letter, “to make a few remarks where I found the expression slightly weak in accurately conveying the meaning of certain phrases…”

One reads those letters and feels a void, wondering how it is possible for intellectuals not to be given their rightful place and role. How can their souls be wounded by a neglect that is often intentional? Without their tireless work, Albania cannot be built.

This is why the toil of all those who bring these figures closer to us takes on special significance. This is why we must always be grateful – not only to creators like Prokop Gjergo and his peers but also to people like Sali Hidri, who know how to choose and treat, as true Albanians, figures so precious to the nation; especially those who, at the marble cutter’s, take the measurements for their successors./Memorie.al

![“Count Durazzo and Mozart discussed this piece, as a few years prior he had attempted to stage it in the Theaters of Vienna; he even [discussed it] with Rousseau…” / The unknown history of the famous Durazzo family.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/collagemozart_Durazzo-2-350x250.jpg)