Dshnor Kaloçi

Part seventeen

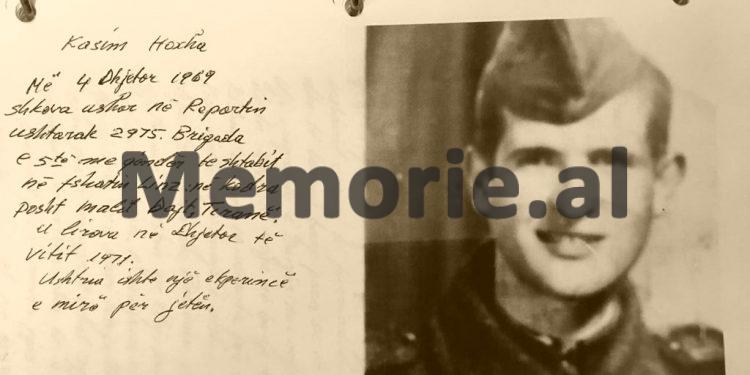

Memorie.al publishes some parts of the voluminous autobiographical book in manuscript “Beautiful land, ugly people” (memories from hell) by the author, Kasem Hoxha, originally from the village of Markat in Saranda and living in the USA since 1985, when he fled Albania after suffering ten years in the prisons of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime. The whole sad and painful story of Kaso Hoxha, from the life and hard work in his village in the southernmost part of the country, the dissatisfaction with the regime and the first poems of a political nature, how they fell into the hands of the State Security and who were his relatives who spied on him, the arrest in the office of the Chairman of the People’s Council of Markat village, by the State Security on June 21, 1973, the investigation in the Saranda Branch of Internal Affairs, the trial against him and the sentence with 10 years in prison for “agitation and propaganda”, staying in “Kaushin” of Tirana (Ward 313), and the prisoners he found there, being sent to Spaç and working in that camp with criminal and “soft” police officers, the accomplices of description of their “portraits” with positive and negative sides, release from prison and return to the countryside, escape to Greece and stay in the Lavros camp, gaining political asylum in the USA, correspondence with Amnesty International, e London branch, inf information with the data he sent to the prisoners of Spaç and the communist regime in Albania, to the creation of a new family and life and work in that distant place with the Cham community divided by the intrigues of the people of the State Security from Albania operating there.

Excerpts from the manuscript book, “Beautiful land, ugly people“, (memories from hell) of the author, Kasem Hoxha, sent by him exclusively for Memorie.al

Prologue

Dear readers!

Do not pay attention to the title I am presenting to you, I mean, if you are not patient to read this collection of memoirs, if you want to forgive the author, that his style is pale, uninspired before this drama of great, of my people, of my martyred nation.

My characters are not created by my imagination, but are real people, they are your brothers, your fathers, your relatives. The events are not fictional, but real and lived. You will convince yourself, only after reading this summary with memories. You will find something from your life, something real from the lives of your fathers, your mothers, your brothers, how they suffered and how they died.

I wrote this collection of memories about the legacy left to me by my friends, for the world to learn the truth, how innocent people were tortured, how they suffered, how they died, in the camps and prisons of the executioner, Enver Hoxha!

I go with the hope that any reader, Albanian or foreign, is not left with hatred, from criticism, beating opposing opinions, as it is the best way to find the truth. The title of the book, “Beautiful land, ugly people”, will anger the reader, but in the end, I will conclude that I have the right to call it “The 45-year era of the satanic communist regime of Enver Hoxha”: Ugly.

I, alas, for the misfortune I had, saw and lived the great drama that happened before my eyes. I am neither a poet nor a orator, I will need hard work to escape the literary mistakes in this historical book, which can inspire future poets and writers, on the tragedy of our time, of the darkest time of my nation !

Ladies and Gentlemen, I wish you all freedom and peace…!

Kaso Hoxha.

Llavrio, Greece 1985

Continued from the previous issue

The last two nights in Spaç prison!

I came out of the iron gate where a little higher Xhelali was waiting for me, who grabbed my bundle of clothes, while I, being physically weak, could barely stand. He begged me to hurry up a bit to take the place where we would spend two cold nights, the next day which was November 14th, the clothes would be handed over and the settlements to the account. Here were some barracks, other than those where ordinary crime prisoners lived.

These were a total of 30 convicts for ordinary crimes and they were released all but one, who was sentenced to 15 years in prison. Ordinary crime prisoners lived apart from us, I mean the large prison for political prisoners, and the “ordinary” as they were commonly called, worked to secure the prison, as well as to maintain the barbed wire fences. They talked without any fear to political prisoners.

The sky was heavily laden with black clouds and heavy rains were falling. We put the clothes on some benches between the barracks and I told Xhelal that we had to find a place inside the barracks to spend the two nights. Crowds of prisoners had opened all over the barracks of the ordinary convicts’ camp, some eating, some gathering wood to light a fire, because it was cold. Dozens of fires were lit, and smoke covered that mountain hole, where the cheering voices of the prisoners were buzzing.

To keep calm, they sent only one policeman, Mark Mark, was his name. He blew the whistle and ordered all the prisoners to gather in the square between the barracks, and after we had gathered, he announced: “Now listen, do not make noise in the first place. Second: do not make a mess, because it is one o’clock, who will eat lunch, they will leave in a row for one, from the upper gate and we will go to the big prison canteen. “You will get food there and you will be back here as soon as possible,” police officer Marku concluded.

Xhelal Çami, friend and brother, I am alive from him

This policeman, Mark Mark, was held for good by the prisoners, and he himself did not spare his kind words, as he wanted to express joy for our release. His black face, as if it had turned a little pale. I noticed Xhelal with the tip of his eye, standing next to my right arm, how he reacted from the good words of policeman Mark! He came to me to laugh and immediately for Xhelal’s hatred for the police, as he openly expressed it with his appearance. He had clenched his jaws so much that the nerve of his cheeks trembled as if he wanted to jump them out!

Xhelali, he was a nervous guy by nature. The humanization of his soul transcended the limits of any kindness to friends. As loving as he was with his comrades, he was just as ruthless and hated for the spies of vicious people. I would say about Xhelal, that he was the virtue himself and I had the good fortune to meet that man in very difficult moments. We formed a sincere, rather than fraternal, society that enabled me to get to know his soul deeply. Or rather, ‘I was him, and he was me’.

To me Xhelali was my savior, his sacrifice was incomparable, as my people had abandoned me all but three sisters. I was introduced to him, who became my irreplaceable brother and friend ten times. I am alive today because Xhelal did not let me die. Xhelal was respected by all the prisoners, in appearance he seemed to impose such a thing on the people. He had a magical power in his appearance and in his gaze, his gaze enchanted, as the gaze of the serpent, the bird enchants!

His tall and muscular body made him afraid not only of the spy prisoners, but also of the police! The neck was a bit long, holding a head up since I was filled with something, there was no man to turn it back. This was coming from his nerves, which were always tense, which had caused the gray to come out prematurely! His black hair was already almost bleached, his legs developed like an athlete, his strong arms in uniform with triangular shoulders descending to the waist of the ring, gave it all, an elegant body that everyone envied.

I interrupt the description of Xhelal’s portrait, to return to the course of events.

– “How are you going to do it”, I said to Xhelal, grabbing him by the sleeve of his jacket, I was talking about handing over the clothes of the company he had received ten days ago.

He was fired after a year and a half after breaking his arm in the gallery. He sold the clothes he received immediately, so he had nothing to deliver!

“I will go up to the clothes depot,” he replied somewhat thoughtfully, “I can maneuver if I am given the opportunity,” said Xhelali, not taking his eyes off policeman Marku, who still continues to give you commands given by the command.

At the end of that meeting, the prisoners lined up one by one to get food at the large prison canteen. Once we had eaten the food, we would go to the warehouse of the mining enterprise, to deliver the clothes and work materials. The weather was getting worse, an eclipse that darkened and made the sky of Spaç darker.

“I’m going to get the clothes,” Xhelali said, “if you can, take my food.”

After a while I returned with both bowls of food and saw that Xhelali was talking to a boy from Tirana, whom they also called, Xhelal (Haxhiraj), a good man and respected by all prisoners.

“Come on,” I told Xhelal, holding him by the arm to interrupt the conversation, “the food is getting cold,” I continued.

They discussed how the weather would turn and how they would arrange a place inside the barracks to spend the night, as it was raining outside, which made it even colder that night.

It was the hour of appeal, in the great prison beyond the creek, the prisoners had come out on the terrace of the bathrooms and they were watching us, and we were watching them! They remained inside the small prison of the dictatorship and we went to the big prison, where all the people were. From captivity, back to slavery.

We did not feel joy at all, as this was not freedom, as long as an entire people was enslaved, where most of the comrades would remain inside the prison, as long as the dictator lived! The black mine would still shatter who knows how many corpses from our comrades. That’s why we let out sighs when we looked at our friends across the wires!

We placed the straw mattresses in a corner of the shack and sat on them. There was so much smoke inside the prisoners that they could not breathe. The cough of sick prisoners could be heard from all sides. In that barrack without a door, without glass in the window, we would spend two difficult nights, but the second night would be more difficult because we would hand over the blankets. The morning of November 14, was cold with wind and rain, which never ceased and it was snowing up the mountain. The police announced that all the prisoners should hand over the blankets and take the money to Financa, those who had it. Those who did not have a job, were given 150 lek (old) for the expenses of the next day.

By 2 o’clock in the afternoon, almost all the prisoners had finished their work on handing over the blankets. As the rain came and got even colder, it looked like it was going to snow overnight. The prisoners had lit fires everywhere inside the barracks to keep warm, gathering in groups, according to societies, and talking, anxiously awaiting the time of November 15, 1982.

Last night on the edge of the brook of Spaç!

The hard night by the edge of the abyss flooded the dreaded Spaç. One more night, one rainy and snowy night, one night to dawn, having no cover except the rags we were wearing! The prisoners who were coming out of hell alive did not even want to know, thinking and holding out hope that it was the last night of their suffering.

It was the last day with my friends, Xhelal Çami and Xhelal Haxhiraj. We stood under the shelter of the barracks, because inside, the smoke of the fires was suffocating. We sat in silence watching the rain falling incessantly and mixed with snow. We were silent, did we not have something to say to each other?! Not! Our minds were far away and dreaming about the people waiting for us, trying to imagine our families.

I left those two babies in my cradle, they were already adults, 12 years old, and my unborn sisters’s daughters were already 10 years old. Our families too must have been anxious and eager to see their man after ten years of absence!

We stood there under the shelter of the barracks with a wasted look across the creek, where the black prison with four barbed wire fences! In that damn place that had consumed our youth, that place that had burned our boyhood dreams, that place that brought out our premature ashes, that place that caused indescribable chronic pain, that place that shortened our lives.

How many groans, how many ohhhe, how many sighs, how many dreams, how many distraught souls, how many hungry bellies, how many closed lips to never smile, how many teary eyes from longing to see their people, mother, father, sisters, children, how much…?! Those concrete walls, cold ice cells, that terrible prison with tragic stories for the entire Albanian nation!

We were already silently seeing that gloomy place with a great and extremely tragic history! The weather seemed to open up a bit, the rain stopped and we started to move around a bit taking a walk in that small square, to soak the limbs.

The director of prisons “advised” his former commander, imprisoned since 1956

Meanwhile, the Director of the Directorate of Camps and Prisons, Mit’hat Bare, arrived, accompanied by a group of police officers. He started meeting and talking to the prisoners and we approached to hear what he was saying. Uncle Iljazi (Ahmeti), a 75-year-old man, was sitting on the stairs to relax. He had been a colonel in the Ministry of Defense and since 1956 when he was convicted by the Tirana Conference, he had spent his life in prisons.

As he passed by, Mit’hat Bare met his former commander, who was now old and skinny.

“Hey, you will be released too,” Mit’hati asked, somewhat surprised!

“Yes, I finished prison and I have a few months left,” Uncle Iljazi replied.

“Stay calm, for he is coming here again,” advised Mit’hati!

“Ohh, I have a life imprisonment waiting for me, the prison that gathers all the people on earth,” replied Uncle Iljazi.

– “So, hmmm…”. Mit’hati turned to him and left.

The night was getting colder and colder, and the black smoke coming out of the fires inside the barracks was rolling our eyes. We were left there under the shelter with no cover and the worst part was that we had nowhere to lie but in the cement. So, we spent the last night without sleep. At 6 o’clock in the morning, the Chairman of the Internal Affairs Branch of Rrëshen came there and more than 50 policemen were following him from behind!

He ordered us to prepare for departure. He announced that the districts of Gjirokstra, Tepelena and Saranda should be presented at the big gate where the trucks entered and left.

I hugged Xhelal Çami and Xhelal Haxhiraj, two friends, my two closest friends. I hugged everyone, saying goodbye to each other.

How did I get 250 pages of manuscripts out of prison on the last day?!

The policemen were lined up and were checking the prisoners when they came out of the big gate, to see if they were extracting any documentation! I was in danger, as I was carrying about 250 pages of documentation, I had recorded the events that had taken place in Spaç during those 10 years, as well as some letters I had received from my family.

I put them in the coat hanger, arranging them piece by piece, and when I showed up at the checkpoint, I let them look at the two bags I was holding in my hand, not giving them the jacket, I had under my armpit.

Excessive courage and consequences, as they could turn me off the road and put me back in jail if they discovered me! I passed with frozen blood. Before we got into the cars, the Chairman of the Internal Branch of Rrëshen, had stopped there at the checkpoint, and asked us all who were being released to we signed a statement that read: “… .that we renounce hostility to Enver Hoxha and would serve where the Party needed”!

This was a great provocation that was done to us before the prison gate came out! To the devil, we had to respond with the devil! Almost everyone from the district of Gjirokastra and Saranda signed it! Only four people did not sign it and those who strongly opposed it were: Bashkim Kodhima, Teli Zhonga, Kosta Qirjako and another one whose name I did not know.

Travel from Spaci to Saranda by open car!

After we all got in the car, they ordered the driver to leave. Meanwhile, our gaze was directed from the prison, where our friends who were inside, had come out on the terrace of the bathrooms and said goodbye by greeting us by hand. How painful were those moments, where some of us even cried…?!

After a while the car passed the turn and Spaç prison disappeared before our eyes, so all of a sudden! We watched the winter landscape of the valley like the precipice of Spaç.

After more than an hour and a half drive, we reached the Fan Bridge. The car stopped at a store. We went to the “Cafe” to get something to eat. Xhelali had 1000 lekë (old) and gave it to me 600. How generous was that good man, and we should have quarreled, but he hardly put them in my pocket!

I took coffee and after mixing it with a little sugar, put it in my mouth. While the others were taking, some biscuits, some curd pies.

On the way we saw people working in the field, some walking down the street to go to work, where everyone greeted us by making us by hand. The car was almost emptied in the Gjirokastra branch of Internal Affairs, where we were left with only 12 people. The night caught us in Tepelena and when we crossed the Muzina Pass, it was 10 o’clock at night. It took us another hour to reach Saranda. We were all wet and the shivers of cold had entered our marrow. “Skoda” stood in front of the door of the Interior Branch and we all came down almost paralyzed by the cold that had frozen us like a turkey! We presented ourselves to the Guard Officer, and he ordered us to go to bed and to appear there the next morning.

We asked him: “Where will we sleep”?! Memorie.al