By Dr. Nikol Loka

The sixth part

“PRENGA BIBE DODA, THE SHADOWS OF A CITIZENSHIP”

Memorie.al / The newest book “Prengë Bibë Doda, a phenomenon in Albanian political life”, by the researcher Nikollë Loka, not only expands the field of historical studies on Mirdita, the Door of Gjonmarkaj and the figure of the Mirdita Prince, Prengë Bibë Doda, but it is also a contribution to national historiography. The very rich archival material, the literature used or consulted, oral traditions, etc., make this book a real study treasure, giving the science of history a scientific monograph that enriches our knowledge of Mirdita, its captains, tradition, history etc. To study such an important and complex figure, as the figure of Prengë Biba Doda, is a high scientific responsibility that not everyone undertakes. Nikollë Loka, has done a great job of research and treatment by the professional researcher, giving us the portrait of the Prince and the general Mirditor, with the true contours. Loka has adhered to the end of space and time, in which the multidimensional events and their protagonists have unfolded.

THE MONOGRAPH “ABOUT BIBË DODA, A PHENOMENON IN ALBANIAN POLITICAL LIFE”, A VALUABLE SCIENTIFIC STUDY THAT ENRICHS THE FUND OF OUR HISTORICAL STUDIES

(By Mr. Sc. Murat Ajvazi, March 2017, Switzerland)

Even the Palaces, which show power and aristocracy, were built late. “The palaces of Gjonmarkaj, with 17 rooms, were built by 4 brothers of the Përsxfa tribe from Bisaku. Above the gate were placed the names of the captains; Mark, Ndue, Llesh, Dede e Nikolle”. (80) Before them, there were the old Sarajes built by Lleshi i Zi and even earlier, the Sarajes of Prengë and Llesh Lleshit (Black Wool). We remember that the Gjonmarkaj barns were burned down three times. We do not have any information about the castle of Dukagjin, and on the other hand, the Sarajes grew bigger and bigger, along with the increase in the power of Gjonmarkaj.

We close the topic on the origin of Gjonmarkaj, with an interesting article by Dom Nikollë Kimza, which is often quoted in separate parts of it.

Nikolle Kimza thinks that we should believe the origin of Gjonmarkaj from Dukagjin, because:

- Gojdhana of Mirdita, which says that the door of Gjomarkaj, is an older chimney than the chimney of Toptan. Before that time, there was no other Chimney on this side, except the Dukagjinvi Chimney.

- The other Gojdhana, which Mirdita and Dera e Gjomarku have, than this Dera, derives from the Dukagjins.

- Urtij himself and the writers at this point, without having more vivid proof that the Gojdhanas, which they told us were from the Dukagjins, do not have any and that the Gjomarkajs do not flow from them.

- The cross made by Pal Dukagjini and Nikoll Dukagjini from the year 1447, he carries it with honor in his hand, at least near Gjomarkaj, they used to say: A shej of the first ones.

Why was this cross found near and near Gjonmarkaj forever, and where is the reason that this cross is: A sheik of his first?

This cross was burned here in the same way as the people of Oroshi, in 1898. This cross is almost completely similar in shape to the cross from Dera Gjomarkaj, in 1809, which is still found today, in the Parish Church of ‘Sails…!

…When Dera e Gjomarku, your truth and Mirdita, says that I am an ace, and it is proof not of Parandesi, why should we deny it…, without having in hand invincible proof, which proves that with him true, they do not derive from the Dukagjins.

After that, one of Gjomarkaj left a document, sod two-three-hundred years, that the door has its source from the Dukagjins, will that document be trusted, or not? It was very poor to have, they told me no…! Are you not stupid, don’t believe me, deny my statements, until the last, true, final word of History comes out to prove that; Gjomark’s door is not the natural flow of the Dukagjins.

No other door depends on this flow, so why should we open the Door of Dukagjin, without knowing for sure, that there is no one there anymore. Well, whoever writes and publishes in these matters, the masses of affirmations, should base them where they belong, otherwise they will be lost, because History did not exist, it remains here and developed. (81)

As Dom Nikollë Kimza himself says; “History pa da, stay here, it developed”. Even today, we still do not have convincing evidence that; The Gjonmarks are descended from the Dukagjins, therefore, in history, a fact that cannot be contradicted is not taken as true, but a fact that can be proven.

How did the power of Gjonmarkaj increase?!

Ottoman documents provide information about the uprisings against the High Gate, in the districts of Fani Magh, Fani Veghe and Mirdita. But even the Christian narrators of the 16th and 17th centuries give a detailed description of places and people, bringing us interesting information about our national history. In the Assembly of Dukgjin, the heads of Dukagjin participated, since their surnames seem to belong to the tribe of today’s Mirdita.

At the top they put their own name; Gjin Gjergji, Gjet Laloshi, Gjon Qefalia, Geg Zajsi, head, first elder of the province of Dukagjin. Among these leaders, Gjon Qefalia, is from Oroshi, Geg Zajsi, from Zajsi and Gjet (Gjekë) Laloshi, is from Fani, the person Marin Bici talks about in 1610. (82)

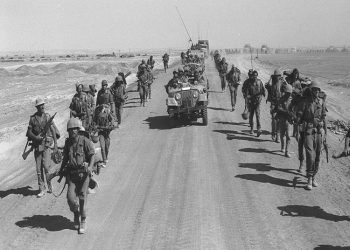

The Mirditas continued the warrior tradition, as mercenary soldiers. The agents of the Kings of France recruited the Albanians from the Catholic tribes of Mirdita and until recently, there was an Albanian regiment in the guard of the kings of Naples, which was called Real Macedonia. (83)

After the failure to establish the feudal-military system in the highland areas, the Turks became interested in their military power. They worked for these highlands to be exempted from taxes in exchange for sending military forces to help the Turkish armies. The populations of the territories of today’s Mirdita did not immediately accept this offer of the conqueror. But when they saw that they did not find support from the princes of Christian Europe, the leaders decided to make an agreement with the Turks.

The obligation to provide a contingent of fighters was recognized in 1681, repeated in 1696 and reinforced during the Turkish-Austrian wars of 1737-1739. The Sultan’s call to join the Turkish forces against Austria set the leaders of the “Mirdita League” in motion. In their assembly held in 1683, they decided: “To go to help the Sultan, with their weapons and clothes, on the condition that the Turks do not harm them with venom, trust and weapons, do not force them to pay tax to give initiative”. (84) The Mirditas fought for the Turks in several battles and as a result of their role, in 1684, the requested privileges were recognized.

In 1737-1739, war broke out between the Christian coalition led by Austria and the Ottoman Empire. In order to face the coalition armies, Turkey called upon the mountainous regions of Northern Albania to come to their aid with their forces. After this call of Sultan Mahmut I became old, the small chiefs of Mirdita decided to go to war alongside Turkey, choosing as the leader of Mirdita’s forces, Kefalia of Oroshi, Marka Kol Gjoka. Sultan Mahmud I, at the request of the Mirditas, for the services rendered in those battles, restored to them the privileges acquired in 1684 and gave Marka Kolë Gjoka, the title “Kapidan”, and bound the Mirditas, an annual subsidy of 100 loads of grain.

…Back here, the Mirditas accepted the sons of this door, to take them to war, whenever they rose up alongside Turkey, or against it, and that door was known as; “Door of the Captains”. (85)

As it appears in the documents, by 1739, Gjonmarkaj had managed to become the leader of Oroshi and won the right to lead him in war. But in this period, the process of forming the provincial unity of Mirdita begins, which, as is known, included Orosh, Spač and Kuzhnen. Since the Highlanders were only used as a military force, the concern of the Turkish authorities was to influence the assemblies of the Highlanders and use them for military purposes. But the introduction of the authority of the assemblies, in the conditions of the complete absence of a local feudal class, was impossible.

Therefore, the mountainous provinces were divided into small administrative units, which were called bajraks. In Mirdi, they were fully settled in the first half of the 18th century, the time that coincides with the granting of the title; “Kapidan”, for the Gjonmarkaj family.

“The birth of Dera e Gjonmarkaj, it seems to me, has a history similar to the formation of the Bajrak organization, during the Ottoman rule in Albania” – writes Mark Krasniqi. (86)

Unlike the other bajraks, which were created in Northern Albania and were directly dependent on the Turkish authorities, in Mirdita, according to the agreement, these bajraks would enjoy autonomy and be governed according to their own laws. But the Turkish administration was interested in having a head of Mirdita, then Trebayraksha. So, in the war, each bajraktar commanded the forces of his own bajrak, while the Captain was the commander of all three bajraks. So it was deemed necessary for this province to have its own representative, with whom the authorities should come to terms. On the other hand, the Head of Mirdita should definitely have the approval of the Ottoman authorities, the rulers with the right of inheritance, came from the house of Kapidani, but of course appointed by the Begollaj and then by the Bushatlli. (87)

The captains did not stand idly by, waiting for Istanbul’s request to send the midday contingent of the next fighters. They were very active in the political scene, until they became an important balancing factor between the two great Albanian dynasties: Ali Pasha and the Bushatllinjes. As is known at the beginning, Mirdita was dependent on Peja and in 1769, it helped Tahir Bey and Hysen Bey, against Mustafa Pashë Bushati, who wanted to separate Zadrima from the rule of the Begollais…! (88)

On April 2, 1769, Hysen Bey gathered an army to fight Mehmet Pasha. John Mark of Mirdita, who came with many people from Mirdita and from other villages, also called for help. (89)

In 1772, the Gjonmarkaj provoked a quarrel with the Begollaj of Peja, who owned the bajrak of Fan, with a completely Catholic population. In that battle, won by Gjonmarkaj, Mehmet Begolli of Peja is killed. It is said that Llesh Gjoni was also killed in that battle. Degrand also informs us about the murder of Llesh Gjon. (90)

In November 1775, the Vice-Consul of Venice in Shkodër, Andre Duoda, addressed the Trade Office of the Republic and informed him that; “Mustafa Pasha took 10,000 men and wanted to go meet Ahmet Pasha Kurti of Berat in Peq, six hours from Berat. Mustafa Pasha was defeated and put to flight, along with the entire army of Shkodra. John Mark of Mirdita was killed in Peq, with sixty of his men, all Christians. (91)

The title “Kapidan”, given by the Sultan, was later confirmed by the two most powerful Albanian rulers, to whom Gjonmarkaj had sent military contingents. Both pashalls, in order to carry out their semi-independent policy from the High Gate, needed the military power of Mirdita.

Prengë Lleshi, being in the service of Ali Pasha Tepelena, received from him the title “Captain” as a reward for breaking away from the Bushatas. (92)

But, after the settlement of relations between the Bushatllinj and the Gjonmarks, Mustafa Pashë Bushati, on November 25, 1815, addressed the elders, the small townsmen of Mirdita with an announcement: “I am letting you know that the house of Gjon Mark has been known, precious, always the first of all Mirdita, and so it will be in the future and, I inform you to know all of you who are mentioned here. This is how it was known by my ancestors, the viziers of our divan”. (93)

Even after the fall of Bushatllinj, the name of the ruler came from the high Ottoman state institutions. In 1837, an order from the Divan of the Royal Army and a letter from Ismet Pasha, ruler of Dukagjin, affirming Mirdita’s privileges, were sent to Mirdita’s bajraks. (94)

In a long period of 60 years, from 1771 to 1831, relations between the Kapidan of Mirdita and the Ottoman authorities developed smoothly. During this period, Turkey did not undertake any punitive expedition against Mirdita, and there were no attempts by the Ottoman authorities to interfere with the powers of the Kapidan. (95)

After the fall of the Bushatllinj, where Mirdita had been their main ally, the High Gate changed its course and began to interfere in the internal affairs of the Province. So, for example, when Biba Doda was in Prizren, Valiu of Shkodra wrote to him to appoint Marka Gjoni as his deputy in Mirdita. (96)

In 1865, Mirdita became an Ottoman administrative unit and the Captain was paid an annual salary of 600 groshis. The administrative council of Mirdita, in addition to Kapidani, had five members, one for each bajrak, who were called by the people the great prides. (97)

Even with this new designation, traditional self-government was respected, but it was intended that traditional chiefs would play the role of administrative officials and as such, be more interested in Ottoman laws than in their canon. Under the orders of the captain, there were also twenty boys. These twenty-five people were Mirdita’s administration. But the Captain-Governor, for his administrative and political activity, answered to the ruler of Shkodra. As a government official, he was recognized by the authorities as the holder of the highest administrative and social position in Mirdita.

However, the introduction of Mirdita under the Ottoman administration existed only on paper, since in Mirdita, it was governed on the basis of the Canon and the Captain-Governor could not decide anything without the consent of the assembly of chiefs, or the people of the province. (98)

The change of the name of the province, from Kapidanat to Kajmekamlek, was not merely symbolic. He expresses the beginning of efforts to destroy Mirdita’s self-government, which continued until the Turks left Albania. After the fall of the great Albanian forces, the Kapidans, in order to maintain and strengthen their position in Mirdita, strengthened their ties with the High Gate and distinguished themselves in many wars. But Porta never forgot their participation in the rebellion against it, together with the Bushatlli. However, relations had not reached the point where there were clashes.

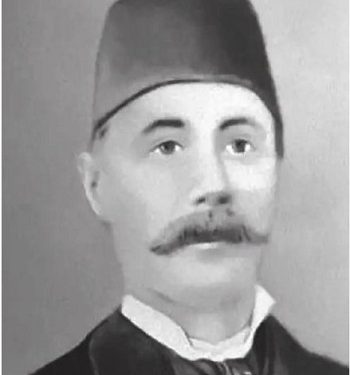

The Kapitans, during this time, regularly participated in Ottoman military campaigns, where the Mirditas distinguished themselves for their bravery. For the great services they rendered to the Empire, the Mirditas, their leaders Gjonmarkaj, from the High Gate, won titles and ranks. Thus, Bibë Doda became Pasha, giving the institution of Kapidani more authority in the eyes of the Ottoman authorities. His son, Prengë Bibë Doda, continued his father’s path and despite the vicissitudes that accompanied him during his life, he was able to gain the ranks and titles that his father had and managed to become, in 1905, Adjutant of the Sultan Abdyl Hamit and commander of the Albanian Brigade of the Palace Guards. (99)

Starting with Biba Doda, at the Kapidanore Door, an independent foreign policy begins to be outlined. In this period, the two Great Powers, France and Austria, were able to gain the right to protect Catholics and, in this context, were interested in respecting the traditional poisons of Mirdita. In the same way, interest in Mirdita and the captains also began to show neighboring countries: Montenegro, Serbia and Italy. The captains of Mirdita were able to draw all the possible benefits that belonged to a Catholic and unsubdued province and used the power of Mirdita to strengthen their positions.

Gjonmarkaj and Kanuni

Self-government in Mirdita had some original features. Regarding the form of self-government, foreign and local authors have named it in different ways, such as: ‘Autonomous Republic’, ‘Military Aristocratic Republic’, ‘Oligarchic Republic’, ‘Peasant Democracy’, ‘Albanian Principality’, Aristocratic Confederation’, etc.

I prefer to single out as the most suitable name the one given by the Abbot of Mirdita, Prend Doçi “Aristocratic Republic, with a hereditary first”! (100)

In Mirdita, in a certain historical period, the institution of the Head of Mirdita, the Kapidan, was created, coming out of the Door of Gjomarkaj, who, despite the authority they enjoyed, exercised their canonical powers in assemblies and not in offices. The captains were leaders with inherited power as well as the elders, but with a higher governing status, which was decreed by the High Gate. But they received this approval only to communicate with the Ottoman authorities, while within Mirdita, their authority was inviolable, because it came from Customary Law. Gjomarkaj, were the first among equals and the governing powers, exercised in the leadership of Mirdita chiefs in times of war and in judicial and eldership activity, in cooperation with the five great chiefs in times of peace.

Mirdita was self-governed by Gjonmarkaj, based on the Canon of the Mountains, in those times, when there were no states and laws, and the Canon was more than necessary to regulate life in the self-governing provinces. The Canon for its radius had the house of Gjonmarkaj, but the government based on the Canon, the family of Gjonmarkaj, exercised it on the basis of customary law. We are confirming this in several points of the Canon. The property of the Gjonmarkaj family is limited by boundaries, like any other property. Any damage done by a member of the Gjonmarkaj family was valued, judged and punished.

The pride came into conflict with Gjonmarku, the people gathered man by house, and the decisions of the assembly, Gjonmarku, are forced to accept them. (101)

Despite the high rank of Gjonmarkaj in the hierarchy of power, the supreme decision-maker continues to be the Assembly. Like the other leaders, they had the right to exercise power, mainly in the assembly and not in the “office”, since they had no headquarters, administration, secretary. The captains were leaders with inherited power, as well as elders, but with a higher governing status, decreed (recognized) by the High Gate and understood by the Holy See.

The power of the Gjonmarkaj family was actually exercised in two directions, first under the leadership of the people of Mirdita, in times of war and in cooperation with the five great chiefs; they formed the Judicial Council of the Canon, which made final decisions. Memorie.al

- Zef Pergega, Sarajet, p.43

- Dom Nikoll Kimza, Investigations on the antiquity and flow of the Door of Gjomarkaj… p. 345-350

- Nikollë Loka, The first door of the Fan, “Ideon” publishing house, Tirana 2001, p.25

- De La Jouquiere Jouquiere, Vicomte de la, Historie de l’ Empire Ottoman, Paris, 1897

- Simon Prendi, History: Middle Ages, Modern and Today, in Mirdita, knowledge of the birthplace, p.65

- Simon Prendi, History: Middle Ages, New and Present Time, … p .59

- Mark Krasniqi, Mirdita has always been a center of refuge for Kosovars, see Gjon Marku, Mirdita Interview, volume III, “Mirdita” publishing house, p.55

- Kahreman Ulqini, Bajraku in the old social organization, p.76

- Stavri Naçi, Pashalleku i Shkodra, Tirana 1964, p. 276

- Excerpt from a diary of the time in Shkodër, -Mahmut Pashë Bushati conducts war in Zadrima, Hylli i Drita 1931, p.203

- Stavri Naçi, Paschalek of Shkodra, …, p.276

- Part from the chronicle of Dajçi of Zadrima, 1809-1810, p.3002. See Hylli i Drita 1931, p.109-113.

- AIH, File 45, year 1850 (1876), p. 5

- AQSH, P.79, File 21, p.6

- AQSH, P.10, File 1, p.1

- AQSH, P.10, File1, p.1

- Petrika Thëngjilli, Popular uprisings in the 1930s. XIX, Tirana 1978, p.253

- Kahreman Ulqini, Bajraku in the old social organization,… p. 77

- Kahreman Ulqini, Bajraku in the old social organization… p. 76

- Joseph Swire, Albania, The Rise of a Kingdom Albanian edition “Dituria”, Tirana 2005, p. 83. Ismail Qemali, Memories, publications “Toena” 2009, p. 360

- Luigj Martini, Bibë Doda,… p. 60

- Ndue Dedaj, The canon between understanding and misunderstanding, “Geer” publications, Tirana 2010, p.13