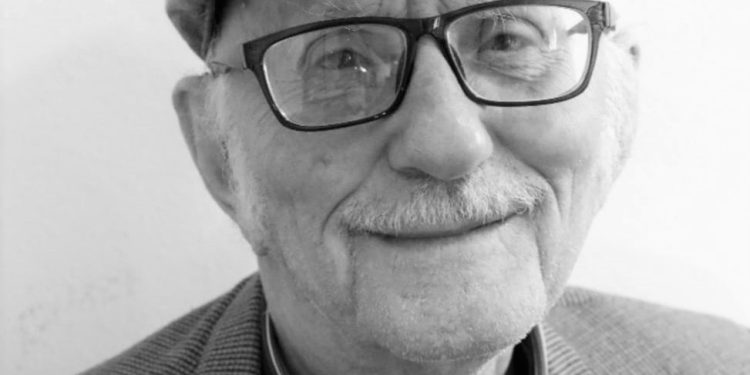

Interviewed by: Marçel Hila

Mr. Lekë, first of all, I thank you for agreeing to give us this interview. What was the reason your father and uncle were arrested?

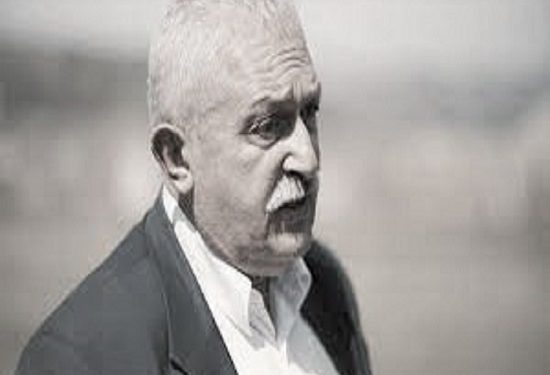

My father, Koço Tasi, was sentenced as a nationalist. He studied law in Italy around 1914. In his youth, he collaborated with Osman Haxhiu in Vlorë, where he worked for several years as a tax officer in the village of Armen. He participated in the first Albanian parliament as a deputy. For the role he played in Albanian politics in the 1920s, he was arrested in the center of Tirana and sentenced to life imprisonment. My father was a nationalist but did not make agreements with any party, except for a little with ‘Balli’, as he saw that ‘Balli’ was inactive, while he sought responses to communism. I have mentioned this in my book! This was the reason he was sentenced: his role in Albanian politics in the 1920s.

My uncle, Akile Tasi, had been a journalist in America, at the “Vatra” association, with the newspaper “Dielli.” He returned around the 1930s to manage the National Library and then became involved in journalistic activities.

As a veteran journalist in America, he took on the responsibility of publishing the government’s organ – “Kombi,” which was later called “Bashkimi i Kombit.” Later, for several weeks, he assumed the Ministry of Culture. This was the reason he was sentenced by the communists.

He got involved in 1943, at the time of the capitulation of Italy, to find a solution to the chaos, since throughout the country there were communist, nationalist, and legalist groups in the mountains, while the country needed a government.

There was a need for an agreement with the German command, which viewed Albania somewhat differently from other countries, as it was a land without an army but had also drawn the attention of German scholars.

There were rumors among the people about an anthropologist who had been very enthusiastic about Albanians and referred to them as leaders in the Balkans, and this consideration reached high circles in Germany; thus, Albanian nationalists dared to lay down some conditions to Germany. If they had a strategic need, since they had troops there, the nationalists sought neutrality, the right to self-determination for ourselves, and assured them that they would not disturb them. This was a lifesaver for many people, who assessed the situation in the conditions Albania was in at that time.

The newspaper of the Albanian government published the communications of all three participants in the war: the Soviets and the allies. I have seen in newspapers from recent years a dialogue between a German major involved in propaganda. He had gone in indignation and complained, and my uncle simply replied that: we have an agreement, we are sovereign and neutral on many points; it’s another matter that you have violated us…! The German major left without saying a word.

My father was sentenced more harshly, to life imprisonment, and he was in prison at the same time as my uncle. My father served 20 years in prison and was released, but he was diagnosed with stomach cancer and died four hours after the operation.

Do you remember how they arrested them?

For my uncle, I know he was arrested in Shkodër. He went there with friends, hoping to emigrate to Italy, but since many had gathered there, those who could managed to get their means and crossed over to Italy. My uncle was a meditative person, not practical, and this is how he remained and was arrested in Shkodër.

My father was arrested right in the center of Tirana. We had fled from our home, as it had been destroyed by the war, and we were at a friend’s house in Përmet, who took us in for two nights. I had gone out, and when I returned, I couldn’t find him anymore. My mother and uncle thought about how to send food to him in prison. About 100 people had been killed inside and in the surrounding areas.

Did your uncle, Mr. Akile Tasi, die in prison? In what year and under what circumstances?

He became ill from liver cirrhosis. They say this is related to alcohol, but he did not drink alcohol; perhaps it was from smoking. We know he became seriously ill and was admitted to the prison ambulance, and then nothing more.

In what year?

In 1961. When I found out he was ill, I asked a doctor, and the next day I went, but he had died: there was no proper treatment.

Do you know anything about his burial?

When I went there, they stopped me at the bars, at the gate, and told me: “Leave, because these things are not disclosed!”

Did you receive any information later about your uncle’s grave?

Yes. Agimi, a boy from Vlorë who lived in Elbasan, and Tomorr Dosti took care of it. They cleaned it up, as the cirrhosis had harmful hygienic effects, and he blessed them, but his agony did not last long. Agimi asked me and gifted me a book with a very honorable dedication to my family. He published it for my uncle’s work. He told me he would like to publish something about my father too.

Were they both in the same prison in Burrel at the same time?

Yes, but when this happened, my father had been taken to Tirana for eye surgery.

This is a difficult question…! If you had met those who did this injustice to your father and uncle, how do you think you would have reacted?

In all this debate about the files, exposing the culprits, spies, I have maintained from the beginning that the devil should be sought out and punished with a lash, rather than those who suffered from the torments inflicted by this devil on the people.

Those who were spies should be categorized: some were prompted by pressures on their families; there were many dirty methods in this field, and these cannot be taken as fully guilty. As for the others, who actively participated in this activity, they certainly deserve to be punished, but it is not really something to discuss in this transition, where former communism is still alive. I know numerous cases of colleagues who write books, looking for the remains, the bones of their relatives, but the officials do not budge from their place when asked where they have buried them.

Do they not tell you? What would you say to those people who destroyed your father’s and uncle’s lives?

I would tell them…! I once spoke in a café; the opportunity arose, not because I sought it. There was a person convinced by the old ways, and I told him that that regime had destroyed Albania. The first fault is the economy, as it hits everyone except a limited number of people; the suffering is additional…! He was not very affected by this, so I ended the conversation…!

Another question, Mr. Lekë. Have you kept any personal items from your father and uncle?

Yes, my younger brother is very passionate about objects; I am not. I keep his manuscripts on “The Philosophy of Law,” which I published in the book about my father. There I also included the translation of an Italian jurist. That was my contribution.

I have a lighter that he kept on the table, a large lighter, as well as a bullet-riddled hat from when Riza Cerova attempted to assassinate him in Athens. In the police records, his name was falsely written as Riza Kardhiqi. That night, my father was with Ali Këlcyrë, and this happened a few months after he published three brochures that assessed the Zogu regime and the Albanian state, in relation to the Muslim majority and the Christian minority.

Specifically, it stemmed from the expulsion of Christian farmers from a village in Kurvelesh, Shtëpëz, as well as from several villages in Kolonjë, and the incident was not isolated. Such acts were happening, where the Muslim agrarian class committed such robberies, while the state protected them because it relied on them. Their language was a bit harsh, but at the moment it was written, the Albanian state was in its infancy, and this was the way it had to be spoken, plainly. They could not endure this, and Riza Cerova attempted assassination, firing four bullets, of which, fortunately, two grazed him and one bullet remained in his thigh.

Since, due to your father, you had a “bad biography,” how did the authorities view you, and have you faced consequences?

Ah, I was helped by a moment of inspiration in 1943 when the opening of the Music School was announced, near Radio Tirana. I liked music, but in a general way. I went there and was chosen for cello. That choice and those two years I studied with my professor, Kaleti, were providential, to say the least, because I lived with the cello until one day others who were prepared came out and pushed me out, releasing me to do manual labor. For about 20 years, I was in the radio and opera orchestra.

Then, what happened to you?

I started working in the vineyard…!

Were you also interned?

After several years…!

In what year were you interned?

Internment came in 1975.

Why?

It was a wave, meaning we were a declassed family. Many were removed; they say about 60 families, but there had been an earlier wave around 1968, so we found other interned families there, in the village where we went, in Grabian. During the internment, my mother, Aleksandra, my younger brother Ylli, my sister Tefta, who was also imprisoned in the women’s prison, and I suffered.

When did you finish your internment?

On October 12, 1990. Exactly 15 years of internment! In fact, the internment lasted two five-year terms, meaning from the third five-year term, we came here. Despite our attempts to find work in Tirana or anywhere else, we could not find anything. There was also a crisis at that time. During that time, I also wrote a book that was worth it, the memoir book about Grabian.

A memoir titled “Grabiani at the Foot of the Hills”?

Yes. I believe it is also a reflection of the situation, the people, the relationships with power, the workers, with prison, the history of families.

Mr. Lekë, has violence been exercised against you? Against your sister?

Violence was exercised against my older brother, who was arrested in 1946 in Poland. He was assaulted by a group: Mitro Jorgji, Skënder Kosova, Skënder Konica, and others.

When I entered that “House of Leaves,” I saw the place where my 20-year-old brother, Napoleon, stayed. I imagined in that moment the despair and anguish he must have gone through there…!

He was sentenced to 10 years but served 7 years because he received amnesty. Not to mention the endless labor camps: in Beden of Kavajë, in Peqin, in Maliq…! In Maliq, there were two sectors with sentenced individuals, around 1,500 of them. Many were left in the swamp mud, alive, until they suffocated. My uncle was also there, and so was my cousin for a year. They were tied up in barbed wire. Terrible…!

What about other relatives? Was violence exercised against them?

Then Tefta… my sister. When she was arrested, they left her with only sweets to eat, without salt, and her blood pressure dropped, and her health deteriorated. They did not allow her to eat normally but permitted her to lie down.

The Lushnjë branch, where she was taken for internment, had orders from the branch chief, Kamber Shehu, who hated us, and he told her she had to stand up from morning until night. This weakened her, caused her blood pressure to drop, and then, in the last month, they allowed her to lie down. They held a ridiculous trial for her, and then she received 3 years of labor camp in the Dumresë region of Kosovo until the amnesty of ’82 came, as she was sentenced to 8 years and was released.

Have you experienced pressures or threats while you were in internment?

We were under pressure throughout the entire communist era. For example, they would suddenly come into our house in Grabian to see what we were doing; there were even cases where they spied from the windows. A neighbor came to us when we were listening to the radio, but we quickly turned it off. There were moments when one would feel terrorized, expecting the worst. With seven people in prison from the wide family circle, including my father, sister, uncle, and even my cousin, who suffered a lot under torture. They hit him so many times behind the ear that he started to lose his hearing; he was sentenced just for having been a judge in Burrel, and there, near Peshkopi, a trial of terror was underway against some of the best families in Dibra; they also implicated my uncle, as an intellectual, viewing him as an organizer. In fact, many people were executed there, but my uncle was sentenced to 30 years in prison, which was later reduced to 10 years. He served 10 years in prison including all those camps.

Has anyone else suffered among you?

Yes, two cousins as well, sons of my uncles. One was 26 years old and served four prison sentences, Bardhyl Linti, and the other, I’m not sure, five years, arrested for terrorism when he was 16, directly from school.

So, your family has suffered a lot?

They have suffered greatly: controls, relocations from our home; we lived on the third floor in ’44 and ended up in the basement before we went into internment.

Have you suffered economically from this entire situation?

Economically, it was tough; salaries were minimal for a basic standard of living. We were also weak because we did not eat much. My father spent 20 years in prison and was released, but then he developed cancer in the lower part of his abdomen and died after the operation.

Did your father die during the operation?

Four hours later, but no one came to see him, neither of the two surgeons who operated on him.

Was it painful for you?

Yes, my mother stayed there to care for him. Apparently, they had put penicillin in the wound, even though he had told them he was allergic to penicillin and had a fever, which is why he passed away at midnight: four hours after the operation.

Mr. Lekë, did you hope that communism would fall?

We were optimistic, and we saw the signs: the economic situation was deteriorating; there were defections of communist diplomats to Paris, Rome, even to the Vatican. One of my relatives told us that wherever they went in European chancelleries, they were told to open the churches, and this was the first step toward liberalization…!

How did you react to the fall of communism in Albania?

With joy and excitement because we were older. I was 60 years old, and we had great hopes, in fact. But we quickly realized that it was an East-West contract to keep the same regime in power, on the condition that they made two concessions: a market economy and pluralism.

We saw how those were falsified, bastardized into a controlled economy, leaving the properties to their offspring so they would have economic power, and communism continued. Only a few paid with a few years in prison, but their influence in politics remained active, and we saw the parliamentary landscape, while oligarchs emerged everywhere in the market.

Mr. Lekë, do you have hopes that the authorities will facilitate the finding of your uncle’s remains?

That message from the Americans gave me hope and that encouraging thought. The Americans do foundational work; they also conduct searches for remains because they have automatic tools, and I hope so, as they have done in some countries.

In Burrel, with the number of people who have died over 50 years, they can distinguish the remains. We made a burial place for my father, my brother, and along with their names, my uncle Akile Tasi’s name is also on the epitaph, but we want to have his remains too.

I hope that the current situation will evolve toward a more organized, legal state that respects norms; first, the norms of freedom and the economic independence of its people and their more intimate, spiritual needs. I hold such hope!

Where do you think these remains might be?

I haven’t heard that any remains have been exhumed from around the Burrel prison, as they do in other places. In other countries, they need to seek out those who have conducted exhumations, whereas in Burrel, I am not aware of any actions taken to remove them. I do not know!

Mr. Lekë, thank you very much for the interview./Memorie.al