By Ahmet Bushati

Part thirty-one

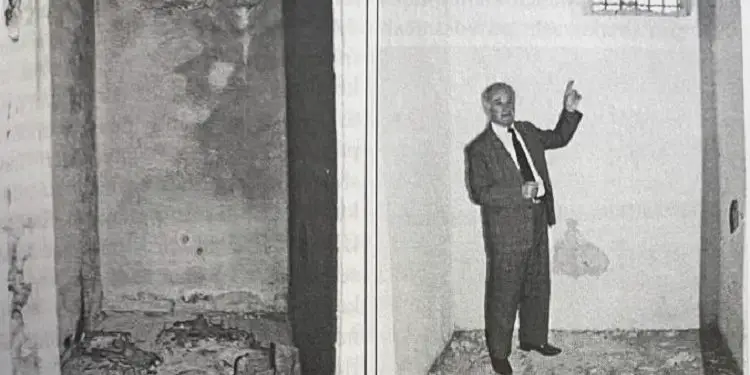

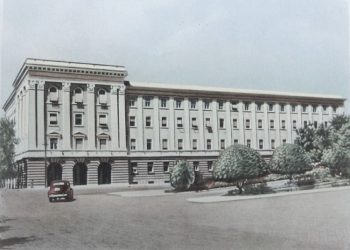

Memorie.al/After the flag was altered in 1944 with the addition of the communist star, Shkodra transformed into a center of resistance against the regime, paying a high price for its tradition of freedom. By April 1945, high school students, already feeling betrayed by the promises of the war, gathered to oppose the new terror that imprisoned and killed innocent people. Communism turned Kosovo into a province of Yugoslavia, while Shkodra was punished for its “historical crime”- its defiance against invaders. The “Postriba Movement” became a tool to suppress all dissent, plunging the city into an unprecedented spiral of suffering: imprisonments, executions, and the destruction of families. The high school students, alongside citizens, became symbols of resistance, while some “young communists” turned into tools of the State Security, leading to expulsions, imprisonments, and internments.

Four times, Shkodra rose in armed rebellion, but history forgot these battles. This book is written to remember the countless prisoners, the tortured, the killed, and the parents who suffered in silence. It is a warning against dictatorship and a plea for future generations not to forget the sacrifices made for freedom.

Continued from the previous issue

In the Footsteps of a Diary

Shkodra in the first years under communism

But within my drama, I unintentionally created a piece of comedy that deserves to be told: It must have been three or four hours at night when the policeman, as if following the order he had received from the boss, handed me over to his office. As on other occasions, Kasem Troshani was there with the boss. They told me that they would confront me with some people with whom I had no social relations. Out of suspicion that I might talk to them, they had thought of putting me under the boss’s desk, which was closed on all sides, except for a gap with an entrance from the back, inside which, when the boss sat down in his chair, he could stretch his legs.

Before they put me in there, as if in a box, they told me very seriously: “You will stay there without moving or feeling anything at all. If you play a little, little by little, or if you only say one word, or if you even cough up a single thread, poor you, then you know for yourself”!

With my hands tied as I was, I lay down under the table with my head in front of me and my legs sticking out from its invisible side, and suddenly I heard a car drive into the yard of the “Branch” which must have been the one that had brought from one prison to another those who, one after the other, would be brought in for me to listen to. The words are similar, because I was dying from the sleep I had been in for several days and had just woken up from the cold of just as many days, as soon as I came into contact with the wonderful warmth of that wooden floor, my eyes instantly closed and a deep sleep immediately engulfed me. When they woke me, while I was falling into the deepest sleep of my life, I did not know how much time had passed until dawn and I also did not know how many and who had been there who had come and gone talking about me, while I had continued to sleep. Kasem’s boss had not even thought that I had been asleep all that time.

After they had touched me with their hands and feet, I emerged as if from a trap, dragging myself backwards, and for some reason the entire environment there, walls, light, people and everything, seemed to me to be enveloped in a murky pink fog. Chief Lilo, now even more energetic and as always with strong theatrical gestures, would order me in a tone to sit on a stool in front of his table and he himself would stand right next to me. Certain that I had listened to what the people brought there from another prison had declared about me and convinced them that I had finally become close to them, he would put his lips together as if in a bitter gasp, and ask me ironically: “Well, now, what do you have to say? Did you hear them”?! “Yes”, – I answered. And Lilo continued: -“So, you already admit it, huh?”

Chief Lilo still believed, not only that I had listened to them, but also that their statements were enough for me to start testifying. I, not knowing what specific things they had talked about, answered seriously: “No, I don’t admit it, they’re not true”! Chief Lilo kept beating me for several minutes, shaking his index finger forcefully in my face, and finally ended this session without even touching me. If there was ever a Security chief in Albania who, on any occasion, would have given a performance for his subordinates, it was Lilo Zeneli. The next day they put my sleeping bags back in as well as my homemade food. That’s how those Sigurimi investigators had it: they would take you to the edge of the grave and then bring you back to life, as long as you didn’t sign the process. Often, the prisoner would have the fate of being like a soccer ball, at their feet. That’s how the investigator from Dibra e Madhe, whose name I would never learn, began to question me twice a day.

Except for the first few days, he seemed to be treating me well. Sometimes he would ask me about things that had nothing to do with the reasons for which I was in his office. Sometimes, noticing his somewhat impenetrable face, I would doubt his polite attitude, but still, even if it was a trap, I had nothing to lose if I pretended to believe him. It had happened several times that during the time I was being questioned by him, Chief Lilo would suddenly enter, who, as always, would address the investigator only with a strong “Huh?”, a question to which the investigator would stand up as a sign of respect for the chief, or as if after the agreement they had made earlier, would answer: – “Comrade Chief, this one continues to resist. He is showing his determination”! – and Lilo, who walked from one office to another without anything on his head, as if he were at home, would utter one of his standard words and run away. At the end of the first cycle of torture, they torment me more than ever.

After about ten days of me struggling with the “mattress” and the “food” that they had brought me again, on the morning of a Wednesday, suddenly Ismail Lulo, as if following the order he had received, brutally took my belongings outside, at lunch he did not give me food or water to drink. They also squeezed my hands harder than before. All this let me understand that they were starting to do something with me. That same morning, the investigator called me into the office, and as soon as I sat down on my usual bench, unlike other times, he looked at me quite seriously. “Did they take away your sleeping clothes?” – He asked me briefly, and more seriously than other times. – “Yes” I answered, and he continued: “You will not receive food or water, and you will remain tied up day and night, until you agree to the trial”, and trusting the torture that had just begun, he did not speak anymore, but returned me straight to the dungeon.

Thus, without putting anything in my mouth, without a bed and with my hands that were more and more coming out of my shackles every day, I spent the first five days, and on the evening of the fifth day, Ismail Lulo, again as if following the order he had received, wetted my cement with water to cool it. And of course, it was still winter. The next morning, at the first session of the sixth day, the investigator said: “You don’t see yourself as you are. Now I’m speaking to you honestly, because I feel sorry for you, because you are young. You would do well to give up resistance”!

And he continued: “I’m telling you how, after the experience we have, a condemned man like you, without bread, water and without clothes, sleep in winter, and in your condition, on the sixth or seventh day, you will surely die”! During the ten days that I would go through that final torture, I would only drink water twice in secret from the interrogators: the first time was one day when, after realizing that the guard on duty had been replaced by a new policeman who knew nothing about the measures taken against me, I made Shurdha walk down the corridor, moving the tips of my bound hands under the door, which caught Shurdha’s eye and he immediately opened the door for me. As always, I asked Shurdha for water by making signs. Knowing my punishment, he thought for a moment, looking at the policeman and, without delay, closed the door for me, and in two minutes he returned with a one-liter bottle full of water.

I had been thirsty for several days for a drop of water! It had never happened to me in my life that the sliding of water through my throat felt so cold and sweet, as if it were passing through a glass tube. The second occasion was another time, during that period, when one day I took the courage to ask a policeman named Hajredin for water, which was the most serious of all the policemen who served there, but who I nevertheless believed felt sorry for me. Without hesitation, he called Shurdha, and with signs told him to bring a jug of water, because supposedly the dungeon needed to be cleaned, which Shurdha quickly and willingly did, having understood Hajredin’s trick better, who in that case was somehow trying to protect Shurdha as well.

As I would later learn, some prisoners in such conditions had drunk urine. At dusk on Friday evening, after a full ten days of being under this torture that had begun on Wednesday morning of the previous week, Qemali, a good policeman, entered my cell with keys in his hand. This Qemali, since I had been arrested, had made it a habit to open the door of my cell every day and, without speaking, with red, tearful eyes, to watch me for two or three minutes, and as soon as I opened my mouth to speak to him, out of fear, he would immediately close the door and leave. I was convinced that this Qemali must be connected to someone of mine outside.

This last evening, as he was being led into the dungeon, red-faced and with obvious regret, he said to me: – “They want you upstairs” – and helping me to stand up, taking my hands in his and shaking his head, he was noticing how they were swollen and inflated like two large blue balls from the chains that were too tight around my wrists, thus obstructing the circulation of blood in them. After a deep sigh, Qemali began to loosen my chains, perhaps more than I needed. When, after an hour, the evil Sirri Çarçani saw my hands somewhat free from the chains, he would call Qemali to the office and threaten him as a prisoner is threatened and not a policeman; as if he were in the service of those he was supposed to be.

When we left the dungeon, Qemali, noticing that my legs were not supporting me, took my arm and walking slowly through the evening twilight, we arrived after a while at the office of the investigator from Dibra, who for his part, after observing me without speaking for a few moments, said in a low voice: “Go over there by the stove”. I would never forget the warmth that I immediately felt, even physically, how it had immediately entered my entire body, frozen like wood, as if it had entered like a strong, burning heat, for several days. After about twenty or thirty minutes, the investigator, breaking away for the first time from the papers he had on the table, addressed me gently: “Did you get warm?” “Yes,” I answered, and he continued as if with regret: “I have orders to get wet again tonight” – and while he was calling the policeman with a bell in his hand, the door flew open and inside, like a beast, Sirri Çarçani, whose face I had not seen since the first days after my arrest.

He entered there with furious eyes and as if he were playing with his mind, he might as well have been drunk, and without wasting a moment, with his face as grim as ever, he addressed my interrogator in an intemperate tone: “This one again, no?” – And without waiting to receive an answer from him, he quickly took off his cap and hat, unbuttoned his military jacket with many buttons and immediately rushed at me with the fury of a savage. At first he started hitting me with all his might, punching me in the face and, wherever he could, with the strong toes of his military boots. Although I was barely able to stand, I continued to stand leaning against the wall and endured his blows without feeling them. He kept hitting me, and kept screaming like a madman. As savage as he was in spirit, he was even more vicious in speech. If it were possible for the evil and vagabond Sirri Çarçani to answer for one thing, above all he wanted to give an account, not for the tortures he had inflicted on his victims, but for the insults he had inflicted on them.

For a while I continued to stand, regardless of the blows he gave me, but when after a while he took the stick and was hitting me with it wherever he could and with as much force as he had, and when my face was covered in blood and sweat, so that I couldn’t even look at it properly, then my strength gave out and I fell to the floor, right next to the stove, red hot from the fire. If I lay down and stayed where I was, he would continue to hit me with the stick and sometimes with his kicks. There came a time when sweat was dripping down his face and, from exhaustion, he could barely breathe, so that at one point he even started to take breaks.

Meanwhile, I, exhausted as I was, could not get enough breath and did not have the strength to get even a single word out of my mouth. I gasped, gasped for a word, for a single word that I would address to the most evil person, Sirri Çarçani, a word that could be “vile”, “criminal” etc., and since I could not articulate even a syllable, because I could not get enough breath, I was forced to suffer great anger within myself. And I did not have the strength to even move away from that stove, which they lit very hot, which was burning me like an oven, near which I had fallen, unable to move. He had decided that without any further action that night he would do something to me. It is possible that on that occasion, he wanted to give a lesson to his subordinates and the boss himself, proving to them how to finish a job with an “enemy”, that is, to achieve in a single night what the others had not achieved with me, during a month and a half.

Finally, as if to put an end to the torture, after a few hours of it having begun, Sirri Çarçani remembers another thing: to take burning wood from the stove and to throw it at my face and head, which had completely burned me. Since he did not stab me or kill me, in the bright mind of the criminal Sirri Çarçani, sometime in his later days, another idea would flash: to try to put the wood in my eyes, to light it. So, several times, screaming like a rabid animal, he would ask me to keep his eye open when he brought the kindling closer to him, but his eye, under the effect of the heat and light of the kindling, would close just as many times of its own accord.

He would try to touch my sense of dignity when, like a spoon, he would continue to shout at me louder: “Open, open your eye, you coward, opens it, I tell you!” – and I, who had been left speechless, but who was determined to make any sacrifice, except to prove to that beast that I was not afraid, not of the burning of one eye or of anything, would stick my face out as far as I could, with one eye open towards the kindling, but which, as I said above, even though it opened hard, would continue to close again of its own accord.

Late, so late that perhaps it was not long before midnight on a winter day, everything finally settled down and for a short time, peace fell, creating that indeterminate state that usually occurs after the end of a battle. A good few hours had passed since the dusk of that night. I had remained stuck in place, near the stove, unable to move at all, while I was unable to even breathe. Even Sirri Çarçani himself, who by then had exhausted all his physical energy, seemed quite tired and nervous, which was indicated by his irregular breathing and the sweat that was running down his face. He had his head resting on the shoulder of the investigator from Debar, and without ever taking his eyes off me, he would speak to him with a forced smile: “Look, look at the dog shaking its head at us!” and indeed, since I had no strength to speak, in response, I would shake his head with clenched teeth.

Finally, Sirri Çarçani, after a silent break, with a new decision at the head, dueled from the office along with the entire investigator, leaving me under the supervision of Nurçe, the police officer who had repeatedly harassed me with words, but who at that moment was supposedly showing them his concern for my situation. During this time, Nurçe, addressing me as if in pain, would say to me several times: “What have you done, you black man?” and I, who did not believe in his sincerity and did not forgive him for the numerous harassments he had inflicted on me, once said to him out of anger: “You are the one who knows my business?”

Although humanity had been suffering the savage communist terror for more than three years, few in Shkodra could have imagined what was really happening in those late-night hours in the death offices of the Sigurimi. They could not imagine, as they would have liked, our sad homes, our friends too, who trembled with fear of arrest; our city, with its deep anti-communism, could not imagine what could really happen in those mysterious offices, where at the hands of the communist criminals of that cruel Sigurimi, some of its best sons had lost their lives, life or death, whom Sirri Çarçani and his friends had considered as common objects of their criminal work and for whom deception, torture, murder, as well as their own sadism, would be an inseparable part of their most inhuman arsenal.

After about half an hour, Sirri Çarçani returned to the office. He sat down at a table; he would continue to remain silent and serious, supposedly dealing with whatever papers he had in front of him. The scenario had just begun. As a few more minutes passed, suddenly it was heard that down in the yard, a car was driven more loudly, which broke the deep silence of the night, including that of the office, where until then no one was speaking. There, too, the heavy and prolonged silence, as part of the scenario, was designed to possibly speak more than the “advice” that that criminal investigator would give me after a few minutes, supposedly “softened up”, before the death of a young man.

It didn’t take long before a captain arrived, who, after marching through the office in a military manner, stopped in front of his superior, Sirri Çarçani, reporting to him in a clear and decisive manner: “Comrade …, everything is ready, the car, the team and the queleshja”. I would never learn what the word “queleshja” meant in that case. However, Sirri Çarçani, believing that he was taking advantage of my moral state created by the solemnity of that fearful atmosphere, when the fate of my life was supposedly at stake, approached me, and in a humane and advisory, but also serious tone, he was telling me: “It’s the end. Think, think again, otherwise they will take you to Zalë i Kirit now. All measures have been taken. You heard it yourself”.

After I answered him with the words: “I don’t have to think about it,” he ordered the captain and Nurca to stand behind me: “Take it,” and he himself left the office. With hands tied in front of me and with Nurca and the captain holding my arms, we left the office towards the yard and the car. That they would take me to Zalla i Kirit, as per the scenario, I believed it, but that they would shoot me, no, given my age, although not even the shooting itself would change my mind. After we went down the stairs and were about to go out into the yard, the investigator from Debra was running after us from behind, supposedly for something that had come up, before we went where it was finally decided. The officer in question called out: “Go back, just for an explanation.”

There was nothing that could break the heavy silence of those minutes, supposedly the last of my life. Even Nurçia and the captain were not left alive. The scenario was being played out by everyone. They made us wait a few more minutes in the corridor, far from the other offices, where it was planned to take me. From the door of that office came Sirri Çarçani who, as very preoccupied as he seemed, spoke to me in a low but determined voice: “Look, we will confront you with a man, whom you will only listen to and not say a word to and not even look at his face at all, do you understand?” In response I affirmed; “Okay”. The person I would be confronted with that midnight was a friend of mine. And I can’t know what he must have felt when he saw my face covered in black soot stains, mixed with sweat and blood, and with hair standing on end. I can’t know what his impression must have been before this shocking sight of mine, and I also don’t know what she said to him?! I found my friend standing there, frozen like a tombstone, at the entrance to an office surrounded by three or four Sigurimi officers, two of whom were Sirri Çarçani and the investigator from Dibra.

As soon as I entered there, I turned my gaze towards my friend, and when he approached him, contrary to what Sirri Carcani had instructed me to do, I, with the intention of encouraging him, put my lip on the gas and, calling him by name, asked him politely: “How are you, …”? Sirri Carcani, extremely alarmed, shouted loudly two or three times – “Stop, stop”! – and as if before the fact that he was done, he did not last long with me, but quickly turned to my friend, saying to him: “Now talk about what you met about, where you met, what you talked about at his house, how you talked about the need for the leaflets you were going to distribute” etc., etc. My friend denied it on the spot. Sirri Carcani got furious once again, just as he was furious. They immediately took me outside, and when I, accompanied by two policemen, was leaving through the corridor with the satisfaction of my friend’s good behavior, I heard behind me the nervous screams that Sirri Carçani was directing at him…! Memorie.al