By Bashkim Trenova

Part thirty-seven

Memorie.al publishes the memoirs of the well-known journalist, publicist, translator, researcher, writer, playwright and diplomat, Bashkim Trenova, who after graduating from the Faculty of History and Philology of the State University of Tirana, in 1966 was appointed a journalist at Radio- Tirana in its Foreign Directorate, where he worked until 1975, when he was appointed as a journalist and head of the foreign editorial office of the newspaper ‘Zeri i Popullit’, a body of the Central Committee of the ALP. In the years 1984-1990, he served as chairman of the Publishing Branch in the General Directorate of State Archives and after the first free elections in Albania, in March 1991, he was appointed to the newspaper ‘Rilindja Demokratike’, initially as deputy / editor-in-chief and then its editor-in-chief, until 1994, when he was appointed to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs with the position of Press Director and spokesperson of that ministry. In 1997, Trenova was appointed Ambassador of Albania to the Kingdom of Belgium and to the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Unknown memories of Mr. Trenova, starting from the war period, his childhood, college years, professional career as a journalist and researcher at Radio Tirana, the newspaper ‘People’s Voice’ and the Central State Archive, where he served until the fall of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, a period of time when he in different circumstances met many of his colleagues, suckers of some of the ‘reactionary families’, etc., whom he described with a rare skill in a book of memoirs published in 2012, entitled ‘Enemies of the people’ and now brings them to the readers of Memorie.al

Continued from the previous issue

WITH “HEROES OF THE PEOPLE”

POLITICAL BUREAU AND THE PRESIDENCY

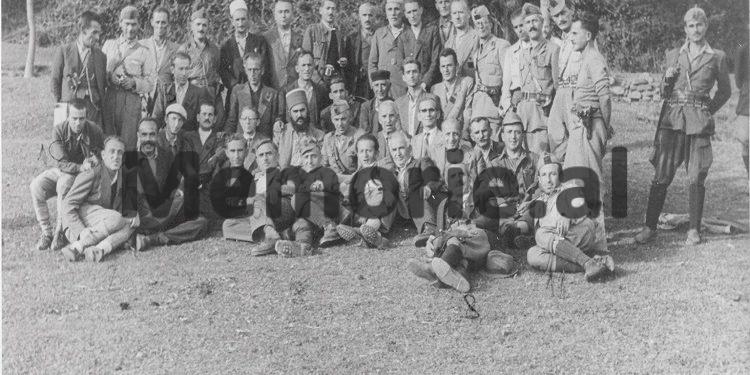

I mentioned, when it was the case, that during the time I worked in the General Directorate of State Archives, among others, I was also involved in the preparation of the documentary volume “Heroes of the Anti-Fascist National Liberation War”. This volume includes various documents on the Heroes of the People, who did not live, that is, who had fallen on the battlefield fighting the Nazi-fascist invaders. Those Heroes of the People killed in the War are left out of the volume, but for whom no documents of the time were found in the Central State Archive as well as in other archives.

If I have known the heroes of the War, through documents and I have spoken about them referring only to the documents, Enver Hoxha, Mehmet Shehu, etc., also decorated as Heroes of the People after the War, I have known them in life. I will write about them below. Even in this case there will be a limit. In my notes I will not write about all the People’s Heroes, who lived in the years of dictatorship, but only about those I met, only those with whom, I can say, I even talked. I will also talk about others, who, although they were not People’s Heroes, were part of the communist dome, loyal and obedient servants of Dictator Enver Hoxha and, as a rule, also his victims. In this case, too, I will confine myself to those I have met and met.

For me, you can describe the former dictator of Albania, Enver Hoxha, and his “apostles” as you want, without error, but never as Marxists or Leninists, as if they wanted to be sold. When I say this, I mean that they never recognized and applied Marxism as a doctrine. Early in their political careers, he and his fellow criminals were truly ignorant of Marxism and later its distorters and unscrupulous demagogues. They covered all their vices with their false allegiance to communism.

You can rightly call them homeless National Socialists because, in the name of his interests, they had sold him and were willing to resell him at any lucrative offer. You can call Enver Hoxha and his sejms feudal-socialists or feudal-communists, because they ruled and thought like feudal lords. Marxism or socialism, Enver and company used it as a religion in their service, just as medieval feudal lords used Christianity, Islam, etc. in their service. Speaking like this about the communist dome in Albania, I do not want to apologize for communism as real or scientific. To me, in all its practical variants, communism has been identified with crime, failure and misery.

I cannot speak of a “real, scientific communism”, which I do not know because it has never and nowhere been practiced. To talk about the non-existent, the unknown, means to guess, why not even to speculate. I prefer to talk about what I have seen, what I have lived. In one of her interviews given to the Albanian press after the overthrow of the dictatorship, Nexhmije Hoxha, the widow of dictator Hoxha, tries to present her husband, no longer as a great Marxist-Leninist, but as a great patriot, as a nationalist progressive. She does not hesitate to say that Enver Hoxha did not break down for ideological problems with the Soviets, as he himself had said in fact for about 25 years in a row, until his death.

According to Nexhmije Hoxha, the break-up with the Soviets was done because this was how the major interests of Albania were protected! Nexhmija acts as a flag dealer to dust, after death, Enver’s black face. In fact, it is not original. Enver was also the one in love with many flags, who grabbed them and threw them down, trampled them with the same passion as he raised them. Patriotism or communism, nationalism or internationalism, lie or truth, friendship or enmity, everything has been valued or devalued by him only if, in a certain circumstance, he has served or has not served his throne.

I had the opportunity to be three times close to Dictator Enver Hoxha, in the first years of his rule as well as in his west, shortly before he died. In 1953, at the age of 10, the school “Kongresi i Lushnjes” chose me and Piro Toporen as its best students. The pedagogical council of the school decided that we should both attend the New Year party at the Palace of Brigades. There, every year, a big party was organized with the best students of the capital’s schools. On this occasion, they were greeted by the “Commander”. (This is how Enver Hoxha would be called many years after the end of the War). As in all other fields, this practice was copied by the Soviet Union. Enver copied Stalin. We children of our generation were accustomed to seeing enlarged photographs of Stalin, surrounded by cheerful Soviet pioneers on New Year’s Eve as well as large demonstrations in Red Square. Even Enver in the manifestations of May 1 on the main Boulevard of Tirana, at the end of them, waited for two happy pioneers who gave him a bouquet of flowers.

As every year-end, on December 31, 1953, the pioneers of Tirana, including me and my schoolmate, lined up in the main hall of the Palace of Brigades, awaiting the arrival of the Commander. We were wearing the pioneer costume, blue shorts, white shirt, and red scarf around our necks. We were instructed to shout and cheer, but not with hysteria, as it became fashionable in the following years. During the war years, the name of Enver Hoxha was not well known to the people. Nine years after its end, there was still little to create for him that cult of personality, which would later identify him with all the old and new dictators.

My meeting as a distinguished pioneer with Enver Hoxha, in the ‘Palace of Brigades’!

Enver Hoxha came smiling between us. The pioneers surrounded him. There was still no strict protocol to determine which of us would approach him, who would embrace him, who would hold his hand to take a few steps with him, and so on. At one point, quite unexpectedly, one of the organizers of the meeting said that the neighboring hall where the tables were set with pastries and fruit was open. The pioneers forgot the Commander and stormed towards the pastry hall. With the Commander remained Piro Topore who had taken him by the hand and I, who wanted to be in his place, but who was content with holding Piros by the hand. Enver Hoxha, after taking a few more steps with us, told us with a laugh, to go where everyone else was already. At the end of the feast we were all given a piece of cloth to make a coat and, to the boys from a small rubber ball, while to the girls from a rubber doll.

Years later I always remember this evening not from the impressions left by the meeting with the Commander, but from the abandonment so natural that the pioneers made him. No one bothered, did not call this course of action abnormal. When Enver Hoxha became the “great and beloved leader of the Albanian people”, something similar, if it happened, would be seen as heresy, conspiracy and betrayal against the “people, the Party of the Fatherland”. This means that in such a case, the inspirers and organizers, the “internal and external enemies”, who were definitely always the only organizers of such deeds and calamities, would be sought and punished.

Years later Enver Hoxha would deserve and approve the whole ceremonial and inflated servile, anachronistic protocol of the feudal imperial and princely courts. His appearance in the courtyard of the communist dome and in public would always be accompanied by hosanara and humility, with praises and titles, which only competed to increase his glory even on a planetary scale. No world leader could be compared to him for his merits and ingenuity, for his courage and bravery! He was the commander of a glorious army and a heroic Party! No one was sung so many songs by the people, by the fatos and the pioneers, in the mountains and in the fields, in every shelter and in every heart! No one was told as many verses, no songs and hymns were composed as he was. God was forgotten, even with a state decree Enver Hoxha brought him “retired”. He declared himself not merely his successor, but the Almighty who will decide on the role of Albania as a “beacon of socialism in Europe”, which will light the way to the aspirations and destinies of the proletariat and peoples around the world!

Two of my Belgian friends, Anne and Mark, invited me a few years ago along with my wife, Desin, to spend a few days at their lodge in Casa Cruz, Portugal. Anne lived for some time in Portugal and took part in the anti-fascist revolution, which overthrew Salazar’s dictatorship. A friend of hers and Mark, Camilo, a well-known anti-fascist figure of the time, had lunch with us one day at a popular restaurant. Camilo, in order to draw the attention of the international public to the violence exercised by the Salazar dictatorship in the country and in the Portuguese colonies of the time, hijacked an offshore ship. A feature film is dedicated to this heroic gesture of his. Then he was a young boy full of energy. He was now old, somewhat sluggish. As an anti-fascist revolutionary, I asked him if he had heard about Enver Hoxha in his youth and what he thought. Kamilo simply told me that: Enver Hoxha has been a lunatic like all lunatics who think they have replaced God!

Feeling like God, Enver Hoxha will also publish his bible “Imperialism and revolution”, which claimed to have “enriched” both Marx and Lenin, so to be the last sacred word in Marxist-Leninist theory. In fact, the Party’s propaganda and the Albanian press of the time referred to this publication, using it as indisputable arguments and as facts quotations drawn from “Imperialism and the Revolution”. It has done the same with the Bible and the Qur’an in theological universities or simply in religious literature and propaganda, in churches and mosques.

How could I secure an invitation to the tribune of May 1, near Enver Hoxha?

I was with Enver Hoxha for the second time, when I was the head of the Foreign Sector of “Zëri të popullit”. This was made possible by my friend Bardhyl Zekia, who worked as an instructor in the Tirana Party Committee. He sent me an invitation to the May 1 rostrum. During the years of communism, except for the last few years, in Tirana as well as in other cities of the country, mass manifestations were organized on the occasion of May 1, the international holiday of the proletariat. In Tirana, on this occasion, on the main boulevard of the city, a temporary tribune was set up. Before her, at a certain hour, the parade of thousands and thousands of citizens was forced to pass full of enthusiasm in front of Enver Hoxha, etc., the communist leaders. Enver Hoxha was the only one who had the right to greet the crowd with his hand, from the height of the tribune. The others just had to smile.

The tribune itself was built by copying the scales of the winners of a championship or Olympics, so the center was somewhat higher and the sides were at a lower level. In the highest place, where at the end of sports activities, the champions ride, stood the leadership of the Party and the state. Among them was Enver Hoxha, as a super champion. In the side parts of the tribune, ie on a lower level, stood the guests, as I was in this case. Before the beginning of the manifestation, Enver Hoxha turned once from one side of the tribune, then from the other side and greeted the guests by shaking his arm up in space. In recent years he replaced greeting, made it more communist, began to greet with clenched fists, as in the War years, as to show that we are still at war.

From the celebrations of this May 1 and from the occasional ceremonial I have not remembered anything special. Time held well and as always, in other similar cases, after the end of the parade, the formula was whispered: “Look, as soon as Comrade Enver comes to the tribune, the sky opens. As soon as the parade ends and he leaves, the storm and the storm begin”! When the weather was bad for May 1 and the boulevard was flooded, the formula that deified Comrade Enver was forgotten, he was silent.

From this manifestation I have in mind something that could have cost me dearly for a lifetime. I had taken with me my daughter, Bora, who was about three or four years old. I also have a photo in the family album where she and I are fixed with a dry face, the director of the Albanian Telegraphic Agency, my friend Taqo Zoto and Gëzim Nushi, a calm and polite boy, who also worked at the Albanian Telegraphic Agency. The photo was taken in front of the tribune and before the start of the May 1 event. Then together we climbed the rostrum and followed the parade of employees and citizens of the capital, which lasted about an hour. Bora meanwhile was upset. For him, I remember, the unbridled enthusiasm of the passers-by who had to declare their boundless love and loyalty to Enver Hoxha and the Party, their cheers “Enver Hoxha, Enver Hoxha”, had no meaning. At one point, at the end, when the crowd, as was the rule, approached something closer to the tribune guarded by the Republic Guard and stood there motionless for about 1 minute chanting “Enver Hoxha, Enver Hoxha!”, She could not bear it anymore. In her innocent childish voice, Bora said: “Ooo, these people upset us too – Enver Hoxha, Enver Hoxha”! Next to me on the podium was the famous Albanian writer Ismail Kadare. I do not know if he heard Bora’s words and pretended not to hear them, or really did not listen to them.

I had blood on my legs. I smiled at him, as if to say “everything is fine, everything is under control”. Then I slapped Bora and said, “Do you see that? I give you a swipe and throw you from the tribune down the boulevard. If her words had fallen on deaf ears, no one would have questioned her childlike innocence. No one would doubt that her words were a repetition of what she had heard about Enver Hoxha from adults, from parents at home, despite the fact that the truth was not so at all. I should be lucky that she did not repeat the word “lugati”, as she said every time she saw the portrait of Enver Hoxha. I cannot say why Enver Hoxha created such a feeling in her. Outwardly he was a real angel. For his crimes, she neither knew nor heard anything, at least in our loyal communist family.

Enver Hoxha to visit my mother’s uncle’s house!

I happened to be with Enver Hoxha in the beginning of 1984, a little over a year before his death. He had come for condolences to the family of the ‘People’s Hero’ Myslym Peza, my mother’s uncle. Enver was accompanied by his wife, Nexhmija, as well as by Ramiz Alia, who would succeed him to the dictator’s throne.

Enver used the death of Myslym Peza to exchange words with the Pesak war veterans, who had also come to express their condolences to Myslym’s family. He knew most of those present since the time of the War. At one point his gaze stayed on my mother. “You are Shyqyri’s daughter,” he told his mother. After these words, his gaze stopped on a veteran, who was sitting next to my mother. This meant that he had no desire to exchange any kind words of kindness with his mother, as he had done so far with the others to whom he had addressed himself.

Enver did not have good memories of his mother’s father, my grandfather, Shyqyriu, and, apparently even after 40 years; he had not lost his temper. In the years of the War, Shyqyri had refused to line up on a front with the Communists. He was killed in the War. According to the official communist version, he was killed in an attempt by the Nazi occupation forces. Officially, he is also a ‘Martyr of the Fatherland’. According to the unofficial version, he was killed by partisan forces wearing the uniform of Nazi soldiers. Plenty of evidence and facts, but also the almost ignorant and discriminatory behavior of Enver Hoxha towards his mother, have made me believe in the unofficial version of the murder of my grandfather, Shyqyri Peza. and a letter from Koço Tashko, one of the communist leaders of the time, sent to the Communist International or the Comintern in the autumn of 1942, seems to me to shed light on the truth.

Koço Tashko was sent by the Communist International to establish the Communist Party in Albania. In his letter, he, after criticizing the work of the Albanian Communist Party, writes, among other things: Shyqyri Peza, the rest of Myslym and none of the Party”! The party had to remove the villagers from Shyqyri. This was done by removing him from this life. Since no one approached the Party they would approach the Muslim. It was up to the party to approach Myslym and thus the peasantry of Peza, which was a hotbed of anti-fascist resistance.

Koço Tashko, an idealistic communist, ended up in the prisons of the dictatorship and died on April 30, 1984 in exile, at the age of 85, also as a result of this letter. I knew his son, Fredi Tashkon, when we were kids. Together, in 1956, we were in the pilot circle at the Pioneer House in Tirana. The district was run by a Russian, one of the many Russian specialists who were in Albania in those years. Fred was a very kind, educated, clean boy. Together we went and visited the school of Russian students in Tirana. There for the first time I tried to work on a lathe. I did not feel safe. He felt different. After the imprisonment of his father, Koço Tashko, Fredi ended up in exile. Further I do not know how his fate went.

My mother was a War veteran, one of the few women with children who had taken up arms to fight the invaders. Her father, as I mentioned a little above, was killed in the War. My father, Selimi, was also enlisted in the National Liberation Army formations. A mother’s sister, Myrvete Peza, along with her fiancé, ‘People’s Hero’ Kajo Karafili, were killed in the war. My uncle, Faik Trenova, was also killed in the war against the Nazi occupation forces. I believe we were among the few families, if not the only one, that had given the homeland so many martyrs fallen on the battlefield. The mother did not deserve to be treated so publicly by Enver Hoxha, who did nothing, no words, and no gestures without a purpose, without premeditation.

The words of praise of Enver Hoxha in my address, as a journalist of “Zeri i Popullit”!

An immediate “diplomatic” intervention by Nexhmije Hoxha made Enver “continue” the conversation with my mother, even though he did not address her anymore. Looking from where his mother was sitting, Nexhmija said to Enver: “She has a good son”. At this time I was standing at the entrance of the room where Enver Hoxha and the others were sitting, who had come to the house of Myslym Peza on the occasion of his death. After Nexhmija, Ramiz Alia also intervened, who told Enver my name and told me. Enver Hoxha told me that he had read my articles published in “Zeri i Popullit” and that he liked them.

“You,” he told me, “have stuck thorns in them, not even thorns but nails.” My articles in the “Voice of the People” have for the most part dealt with problems that condemned the hegemonic policy of the Kremlin lords both externally and internally. Thus, it is implied that, according to Enver Hoxha, I had driven nails into those who in the language of that time in official propaganda were known as Soviet social-imperialists or Soviet social-chauvinists. It was a very big appreciation, but it never served me. In fact, I had already left “Zeri i Popullit” a few weeks ago and started working in the Publications Branch, at the General Directorate of State Archives. This was said to Enver Hoxha, the son of Myslym Peza, my childhood friend, Partizan Peza, who was also an employee of this Directorate.

I had the impression that, after Partizan’s words, Enver Hoxha silently asked for an explanation as to why I had left the “Voice of the People.” Ramiz Alia, apparently, understood him and speaking to me said: “The union has worked well in the newspaper and we have sent it to the Archive for good.” In the State Archives I, in fact, was not sent at all for good; however there was neither the place nor the time to discuss why I had left the “Voice of the People” and why I had ended up in the State Archives. Enver Hoxha continued the conversation, talking about the importance of archives in the life of a people. My knowledge in the field of archives was still very basic. The words of Enver Hoxha made me understand that he was a man of wide culture in this field as well. I, intervened on some occasion during his conversation giving some opinion on archival publications. He listened calmly and continued the conversation.

Two or three months later, if I am not mistaken, I would have the opportunity to understand that Enver Hoxha, despite giving opinions as a specialist in archives and as a deep connoisseur of them, in fact his knowledge in this field was, that at least, incomplete. I realized this not because I became an archival specialist during these two or three months, but because of a completely random circumstance.

In May 1984, the General Directorate of State Archives organized a Scientific Session in one of the halls of the National Historical Museum. Usually, in such cases, in conferences and seminars or scientific sessions, on the walls of the hall where these activities were organized, were placed quotes taken from the speeches or published works of Enver Hoxha. I recommended to the director of the State Archive, Thoma Murzaku, to request from the Archive of the Central Committee of the Party, a copy of the conversation that Enver Hoxha had at the house of Myslym Peza, where he also spoke about the archives. I knew the conversation was recorded. In fact, in any case, every word of Enver Hoxha was recorded to be published later in his works or to be transmitted to generations and history.

Following the request made to the Archive of the Central Committee, in the General Directorate of State Archives, six typed copies of Enver Hoxha’s speech were received. I was given a copy too. Even before starting to work with them, after two or three hours, Thoma Murzaku calls me and tells me that: from the Central Committee of the Party, they asked us to return all the copies they had sent us. We had to wait for other copies, which would reach us later. Actually they did not delay much, but they were no longer either like the first or quite similar to them. A real archival specialist, he had put his hand on the words of Enver Hoxha. We would use his opinion, as the opinion of Enver Hoxha, this encyclopedist and giant of philosophical, ideo-political, economic, financial, sports, artistic, archival, etc., etc.! Memorie.al

The next issue follows