By Mehmet Biber

The first part

– “Albania, alone in front of the world” – National Geographic – 1980

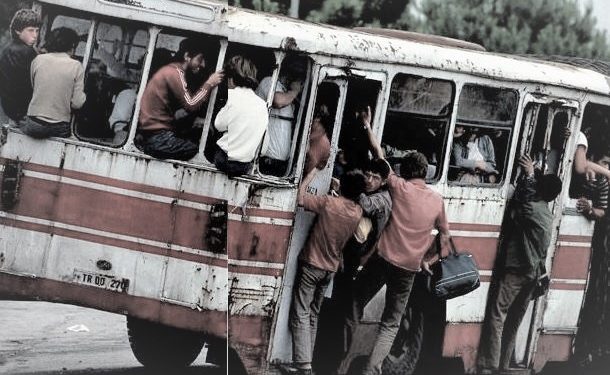

Memorie.al / “Let’s accomplish all the tasks and break the blockade”, is written in a slogan in the Albanian city of Shkodra – but Albania’s isolation from the world is simply the result of its internal politics. Without allies and surrounded by states that have historically had ambitions for its land, Albania has organized itself in such a way that it will succeed on its own, under the strict dictates of Enver Hoxha, who has been in power for 36 years. The symbols of the pickaxe and the rifle predominate in public places. Hoxha, a dogmatic Marxist-Leninist, in 1961 severed relations with the Soviet Union, which he considered “revisionist”, and strengthened ties with China two years later. The road to succeed alone is a difficult road. Cars are prohibited in this country, so Albanians should go this way, on a bicycle.

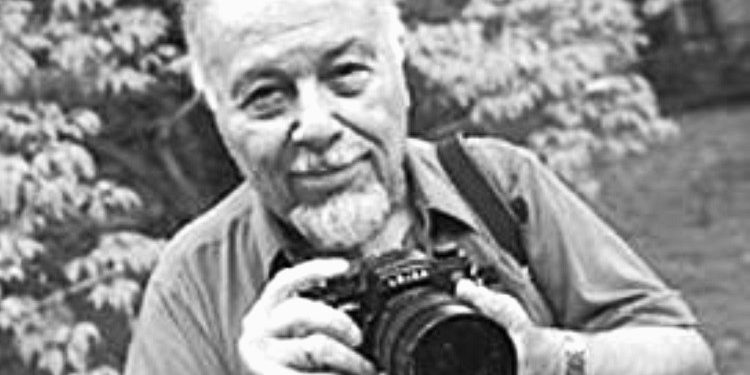

Journalist visits are quite rare. Last year, Mehmet Biber, a Turkish photographer living in Istanbul, was able to secure a visa just a few months after journalist Sami Kohen, another Istanbul resident, had finished a visit there.

From the conversations with Mr. Cohen and his personal impressions, Mr. Biber brought us this reportage, which is the first full reportage on Albania, published in American magazines, for many years.

The report of the Turkish journalist, Mehmet Biber

The small plane flying over Yugoslavia turned south, came out over the cobalt color of the Adriatic, and after turning 90 degrees again, headed for land – Albania.

In antiquity, the legions of Rome coming down the Appian Way to the heel of Italy at Brindisi crossed the Straits of Otranto, landed here, and then marched East on the great highway of war to Thessalonica and Constantinople.

The Goths and the Normans conquered this country. The Byzantines, the Bulgarians, the Serbs and the Venetians exchanged powers with each other. Then the Ottoman Turks ruled for 500 years and turned Albania into the only country in Europe with a Muslim majority. Then came the armies of Mussolini and Hitler.

Today, no international highway connects Albania. The 300 kilometers of its railway do not cross any borders. No foreign aircraft is allowed to fly over its airspace. Semi-empty commercial flights like ours, which are made once every two weeks from Belgrade, should only go by sea and only in daylight hours.

I glanced around the plane’s cabin to see the handful of passengers traveling with me—an old woman, an Austrian professor, a scholar of the Albanian language (which has only distant connections with other European languages), and businessmen coming for to buy minerals or, to sell machinery.

I did not know which group I was in, in the description for foreign visitors defined by the dictator of Albania, the General Secretary of the Labor Party of Albania, Enver Hoxha. He had declared that his country was “closed to enemies, spies, hippies and hooligans, but open to friends (Marxist or non-Marxist), to revolutionaries and progressive democrats, and to honest tourists…who do not poke their noses into our jobs”.

Perhaps the most appropriate definition was that of a commercial agent: “Only crackers, diplomats and journalists, travel to Albania. I was a Turkish journalist, and I had been waiting for over a year for my visa to be approved.

We crossed the coast and were flying over the coastal plain of Durrës and beyond the terraced hills, I saw on the horizon a long line of jagged mountains shrouded in mist, looking like a giant electrocardiogram. Meanwhile, I wondered what I would find in this small country of 2.7 million people, about the size of Maryland, and as little known as Tibet.

For thousands of years, the descendants of the ancient tribes, called Illyrians, have settled in these rocky places of the Balkans – which in Turkish means; “mountains”. Among the peaks that rise to 2,764 meters, they followed an unchanging clan code that wiped out entire families in blood feuds that lasted for generations.

Today the Land of the Albanians is all cooperative. The last bastion of Stalinism, it is the most dogmatic communist country in Europe, stuck under the iron fist of a leader who brought the continent’s most backward country, from the ashes of World War II, on the road to modernization. from crafts and candles, to factories and dynamos.

Here I can see an unusual social experiment: a whole generation growing up sealed inside a hard-line socialist laboratory, defying the world, self-isolated and uninfected by East or West. Mindlessly I rubbed my ‘goatee’ (type of beard with a tip like a goat) and was suddenly stunned, when the thought occurred to me, that I might even lose it!

Albania prohibits the entry of men with long hair or beards, women in short dresses, cowboy pants or other signs of the decadent bourgeoisie. Stories about visitors who had collected a bunch of them and taken them to the airport barber to shave them were not rare.

But the policeman who stopped me at the plane door was more concerned with my passport than my beard, and I landed under the midday sun of a September day in one of Europe’s smallest and sleepiest airports, where shaded by palm trees and orange trees heavy with fruit.

Kopi Kyçyku, greeted me in Turkish. A member of the reception office at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, he would bring the plan of my daily movements to my companion-interpreter every morning.

TO WORK FOR THE STATE

“Plan”. This phrase seems to inspire respect and awe whenever it is used. In fact, in a country as dogmatic as Albania, the word “plan” is sacred.

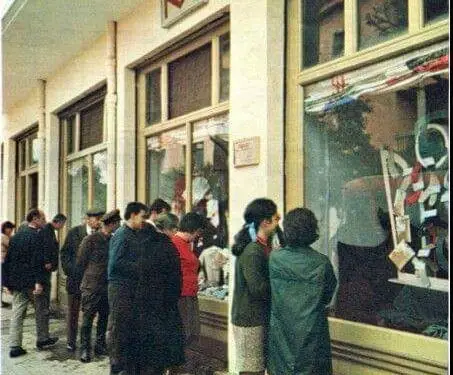

The plan is based on state ownership. Every shop, restaurant and kiosk belongs to the state…! Every taxi driver, barber, waiter, baker and artist works for the state. Peasants work either on state farms, or in state-owned cooperatives.

Coming from a Turkey where inflation is the main problem, I find an undeniable attraction in some aspects of the Albanian economy. There is no income tax. There is no inflation. It is not dependent on external energy sources.

And as long as everything is controlled by the state, there are no price increases – but no wage increases either. Factory workers and peasants receive 600-700 ALL per month; a university professor receives about 1000. Salaries have a ceiling that goes up to 1200 lek, except for senior officials.

By Western standards, wages are low, but so are many of the prices. A kilo of meat is between 12 and 18 lek, bread 4 lek and a pack of local cigarettes, 2 lek. Clothing narrows the family’s economy a little. I saw men’s suits made in Albania, which cost as much as a month’s salary, and which I would not buy…!

Shoes are 100 lek, t-shirts 500 – but the quality is very poor. The plan allows Albania to import up to 250 million dollars, and they are mainly machinery, spare parts and raw materials that must be balanced by exports.

Albania keeps rents low – usually no more than 5% of household income. But officials admit there is a shortage of apartments, especially for newlyweds. Health care and education are free, and Albanians spend little on transportation and entertainment. Tirana offers some entertainment: few theaters, ideological films, operas and folklore programs, but no night clubs, which stink of bourgeois degeneration.

Tirana has more restaurants than other cities, but few can afford to eat out often. In Tirana, a guy can go with his girlfriend to a park, if time permits, or to watch a movie with the favorite theme of the National Liberation War.

Sami Kohen, happened once at a dance evening organized by a company in the Palace of Culture. The young couples laid down their dance steps with some ‘fox-trot’ and old tangos played by an amateur orchestra. Discipline and calm prevailed.

In fact, the Albanian “Cultural Revolution” sets the tone for the behavior and appearance of the youth. Not only long hair and miniskirts, but also blue-jeans, tight pants and toilet, are taboo. There are no drugs, sex, pre-marriage, dirty barsoles or chimcakiza. Rock and jazz music are prohibited.

Foreign visitors usually spend their evenings in the bar of Hotel “Dajti”, in the tavern. “Apart from cocktails and nights at the embassy, there’s hardly any place to go, anything to do or, well, someone to talk to,” a young Western diplomat, coming from a previous post in Paris, told me. .

I used this opportunity to learn something more about the “roots” of Albania’s suspicions towards the outside world.

“If I had been Albanian, I too would have become suspicious”, continued the diplomat. “Throughout history, the neighbors have wanted to grab something from them: Serbia, Montenegro, and Greece have extorted large pieces of Albanian territory. Don’t forget that 1.5 million Albanians live in Yugoslavia today, a figure equal to half of the population living in the motherland.

For 70 years, Greece has been looking for Northern Epirus, which is Southern Albania. While Western diplomats twiddled their fingers, Mussolini marched on and conquered the entire country in 1939. Later, Tito wanted to make it a republic of the seven Yugoslavians. A story like this leaves deep scars.”

Today, Albania does not have diplomatic relations with the USA, England and West Germany. Would this policy work now that they have also broken away from the Soviet Union and China?

“The USA is an imperialist superpower, which is as threatening to us as Soviet social-imperialism or Chinese revisionism,” a senior official of the Foreign Ministry told Sami Cohen. “The Americans made us offers after we broke up with China, but we don’t want anything to do with them.”

“England still has blocked us a quantity of gold worth 40 million dollars, which was taken from us after World War II. Germany refuses to pay us war damages, amounting to 4.5 billion dollars. We will not establish diplomatic relations with any of these countries without first giving us the money.”

THE FUTURE LOOKS UNCHANGED

Today’s Albania is cut according to the image of Enver Hoxha, now 70 years old. What will happen after him? To the publisher of the humorous magazine “Hosteni”, (Niko Nikolës, our note), I reminded him of the changes that took place in Russia after the death of Stalin and in China after the death of Mao. Was there any possibility that Albania would soften somehow after the death of Hoxha?

“You compare us with those revisionist countries”, he replied with a frown. “No, nothing would happen after the death of Comrade Enver. The party and the people are firmly united with each other. His teachings show us the right path. And we will not avoid it”.

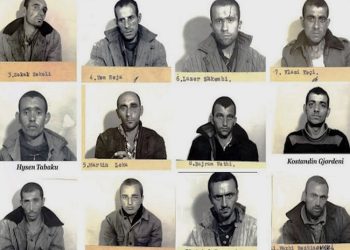

More than opening up to the foreign world, the self-isolated Albanians have their mind set on war. In addition to two years of military service, all citizens who have reached the age, regardless of profession, must serve one month a year in the Armed Forces. Frequent military preparations in factories, farms and offices prepare the population for war.

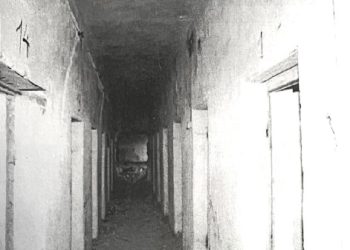

Everywhere I traveled – on the coast, mountain paths, fields, city parks or, between apartment blocks – civil defense bunkers were erected. They look like – and grow like – mushrooms, as is their vernacular name. “More iron and concrete is used for bunkers than for apartments,” a foreign diplomat told me.

I know that Enver Hoxha was worried about the future of Albania, after the death of Tito – and was terrified of a Soviet invasion. But was Albania really threatened?

“We must prepare for the worst,” an Albanian journalist told me. But can Albania withstand the attack of a great power”?!

Albanian weaponry, mostly Chinese, is outdated, and a diplomatic observer told me that it is likely that the Albanians are looking for weapons in Europe.

“Even if the enemy is outnumbered, we can stop them. Our mountains and rivers make Albania a natural fortress. Every attack will cost the enemies dearly.”

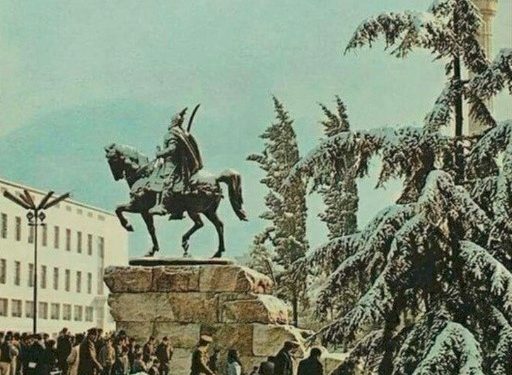

I thought of the stone houses of Gjirokastra and other mountain towns; walls without windows below and turrets above – every house like a fortress, a legacy of centuries filled with blood feuds. I remembered the 15th century castle in Kruja, from which Skanderbeg led a guerilla war against the Ottoman Empire for 25 years.

Gjergj Kastrioti, sent as a hostage to the Sultan’s Court as a child, reached high levels in the command of the Ottoman army. With a new name in honor of Alexander the Great (Iskander Bey, in Turkish) whom the Turks admired, Skenderbeu united and led 300 Albanian knights, to take back the inheritance that belonged to them.

He lived as a symbol of resistance. And under the flag of Skenderbeu – a black eagle with two heads, on a field as red as blood – the Albanian partisans forged today’s independent Albania. Memorie.al

(The report translated into Albanian by “National Geographic”, 1980, was published by “Alxiptari i Italia”)

The next issue follows