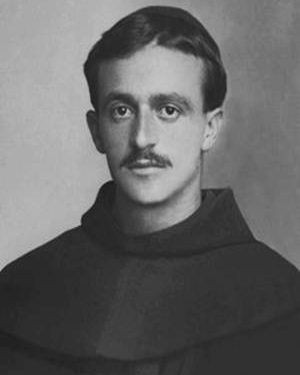

Ejëll Çoba

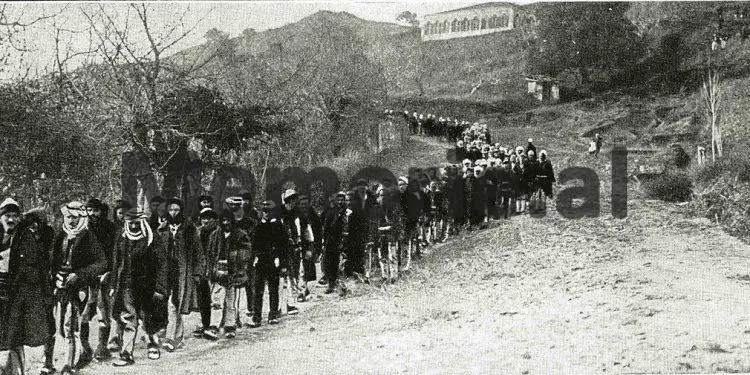

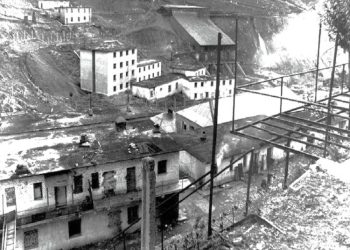

Memorie.al publishes some parts from the memoir of the author Ejëll Çoba, the well-known intellectual from the city of Shkodra, the sucker of one of the most famous families of that city, who after graduating from the University ‘La Sapienza’ of Rome in In 1932, he returned to his homeland where he practiced his profession, pursuing an administrative career, as ‘Dottore in Giurisprudenca’ and then for several years in the senior state administration, where he also occupied the period of occupation of the country, (1939- 1944), where he held several senior positions, as Director in the Ministry of Justice, Secretary General of the Council of Ministers, Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs, etc. His arrest in 1946, (together with his brother, Kelin) accused of participating in the ‘Postriba Movement’ and after a long investigation in Shkodra and Tirana, was sentenced to 25 years in prison, of which he suffered a full 23 years and five months, and five days in prison, in the terrible camps of forced labor, all the way to Burrell Hell. The unfamiliar memories of Ejell Çoba, which come with a foreword by his fellow citizen, the well-known writer, Zija Çela, present to the reader a panorama ‘painted with the brush of pain’, which provides details and details about his sufferings in the camps of the prisons of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, as well as other accomplices, known and unknown names, such as: Father Bernardin Palaj, Guljelm Suma, Syrri Anamali, Ramdan Sokoli, Cin Serreqi, Father Karol Serreqi, Father Filip Mazrreku, Hamdi Isufi, Hafiz Ali Kraja, Beqir Çela, Musa Gjylbegu, Asim Abdurahmani, Kolec Deda, Nikoll Deda, Felatun Vila, Gjush Deda, Sali Vuçiterni, Emin Bakalli, Qani Katroshi, Sali Doda, etc., as well as some names of investigators, guards, State Security officers, such as Fadil Kapisyzi, etc.

Continued from the previous issue

Imprisonments

Memoirs written from August 1973 to the end of December 1977

Only extreme things can be tolerated

Count Rober de Montesquieu

Later in the evening, I proposed to Felatuni that we watch as the lights go out and the investigators leave. A fearful silence had fallen in the dungeon and the cause was not understood. Occasionally, swearing was heard. They are investigators, Felatuni told me. After a while the door opened and two officers came in and asked who we were.

- Ah you Ëjëll Çoba?! How do you sign? – And you put it with your finger on the wall and he approached me to see if he had done well.

- Yes, I answered, being able to hold the gas.

I did not understand the importance of the shape of a firm. Qani Katroshi was told that he was like a stani dog. And with them, laughed pleased and Qani.

The driver was called out and after being caught, he was punched in the chest. He shouted and they, after releasing him, kicked him towards his mattress. He fell down and started shouting: ah, ah, and after they left, he asked us: did they go? When we told him he was gone, he got up and started cursing at them with a rich vocabulary.

I found out that the investigators, when they were doing their day job with the detainees in charge, in the end when they were out of work, they went into the dungeons and watched the young people who had come. On those perils, they distributed for free a number of punches and kicks.

All afternoon until midnight, we waited for such visits. That is why Felatuni had told me to eat before midnight, so that such a visit would not get the food in our throats. And after midnight the light signaled that it would go out. Then the footsteps of people with cheerful expressions were heard. The investigators laughed at their work and hurried to drink a glass so that the night would not catch them. So, we ate quietly. Then we lay down to relax our nerves. But before we fell asleep, screams and swearing were heard. They started to increase so much that I felt like I was in Dante’s hell.

Felatuni told me that they were calling people who were tortured. In this condition one could not sleep. At times it seemed to me as if I knew a friend’s voice. But “kind-hearted” investigators were careful to eliminate such shouts carefully so that families living near the prison would not hear them. And for this reason, they had ordered the prison guards from midnight to dawn to fall on the accordion. The miserable guards, of course, did not hear from the accordion, but their sounds mingled with the cries of the unfortunates and created a bad cacophony. Dante had not gone to hell, to put the accordion in hell, but the Albanian Security investigators did! I later learned that these forms of torture were instructed by the Soviets, through a special code. Of course, we could not sleep at night in this state. Only near dawn, when the screams ceased, along with them did the accordion. We slept until lunch with a bad sleep. In this state the day passed when we too waited to shout like animals.

One day Sali Vuciterni told me:

- I am ready to commit suicide, just to escape torture.

- I told him the same thing.

We were all in a state of fear as much as just the desire to be able to die gave us pleasure.

Qani Katroshi told me that when he was continuing the investigation, to persuade him to speak (this was their expression because they themselves did not know what they were asking), they had escorted him to a dungeon without torture and told him, ae boss kshu do we and you?

He had seen a man stripped to the waist and chained to the window bars. Her legs were just tickling, and her head was hanging over her shoulders. Qaniu had known him. It was Gjon Nikë Vuksani, the former port captain. He had died three days later.

John was accused that when he was in Durrës, he had received five letters in one day from an officer of the British military mission. And that in one of them were 5000 pounds. The desolate John had not even seen them in a dream before, as he came from a poor family in Shkodra. She had studied on a scholarship in Greece, where she was married to the daughter of a Russian who had fled at the time of the revolution. After the Italo-Greek war, he had taken his wife’s family to Albania to save her from starvation. It was said that the frightened brother-in-law, Vladimir, had claimed that John had taken the pounds from the Englishman. Vladimir was sentenced to three years in prison.

One day we learned that in the dungeon next to it (which communicated with ours through a small space where electric lamps were placed) were Hafiz Ali Kraja, Beqir Çela (who had won the flag anthem competition in 1937) and someone else. Hafiz later told me that the investigator had given Beqir Çela a pencil and paper to write all his anti-government political activity. At the end of two or three days, he presented himself to the investigators, but the latter was not satisfied.

Beqiri magnified the story of his imaginary action, but the investigator was dissatisfied. Of course, in these stories were also mentioned people he had known. Hafiz had advised him not to prolong it too much, because then it could have dangerous consequences, not only for the persons he mentioned but also for himself. The answer was that he could not stand the torture. He was eventually sentenced to death and shot. I did not know how many people were convicted because of his fantasies. Apparently, the investigator had recalled a literary essay. Being at the center of a vast network of actions, he could not come out alive. It was the cynical logic of the Security investigation.

False witnesses could not be left alive. A few days later, they called Sali Vucitern. When he returned, he was silent and scared. I did not ask him questions, although I wanted to know how the investigators were treating him. But in the evening of the second day, an officer came to our cell and saw us. ‘You Sali, go to dungeon no. 1 ‘, and mark the guard. Saliu was transferred.

Four days passed and Felatun was released from prison because he had ended the investigation and was awaiting trial. In his place, they brought an Italian, Augusto Betti, who had been an electrician in Korça. He had conducted the investigation. He had been friends with the director of AIPA, in Korça. He spoke very well of the director who had been shot. He considered him innocent. He said that he had been severely tortured. And Bettin herself, had been tied to her legs, to the window bars and leaned on a chair. He hinted that in that condition he had spoken against the director himself. Such torture may have been reserved for him as a foreigner.

Electrician Betti also had to pay for the fascist occupation. He had a 5-year-old daughter and his wife was a teacher. He told me that his daughter before going to bed prayed for her parents, for herself, for the sick, and for the prisoners. I did not understand, he was telling me why he should pray for the prisoners as well. But now I learned that in prisons there are honest people. How hastily people gave me judgments. Life experience is very valuable for man.

In the dungeon we also had a former officer, academic, anti-Zogist Matjan, named, Sali Doda. In the Italo-Greek war, he had been taken prisoner and he had told everything about the positions of the fascist army.

When the Italians entered Greece, they found him and exiled him to an island. They had found his minutes and based on them they had initially sentenced him to death. He was pardoned and taken to Gaeta Prison. When the Anglo-Americans entered they released him and apparently held him for some time to prepare him for diversion.

In 1944 he was parachuted into the areas of the National Liberation Army, and he was introduced as an officer. They had offered him to take part in the war as an ordinary soldier. He had not accepted. After two days he was allowed to return to Italy by submarine. But three days later, he had returned from Italy to serve me without rank. He had taken part in the fighting. After the break-up of the communist government with the Anglo-Americans, he was arrested in 1946, accused of being an American agent. When we were talking, I did not hesitate to tell him not to be surprised about the investigation. Later after serving 10 years in prison, he was released.

During my years in prison, I often met such young men as the war and circumstances threw them where they could. During the days I spent in the dungeon, I heard some voices and laughter, and feet running. I did not understand what was happening. And I looked questioningly at my friends.

Those who have been in dungeons for a long time explained to me that it was a pastime that investigators allowed themselves to do during the day. Each investigator would take the defendant under investigation or torture, and after lining them up at the end of the corridor, they would get on their necks and the prisoners, along with the officers on their backs, would run and compete with each other.

Of course, the “horseman” investigator took an active part in the race by shooting the “horse” in the groin, or where possible, the investigator who was on the “horse” ‘s back the fastest.

Just as I was anxiously waiting for my turn to be laid to rest, the wet days of that winter were passing, when one day a guard came and called me. He escorted me to the captain’s room, where there was a bed and a table. There was waiting for me a first-class captain, dry on the body, pale in the face, with a thin voice as if he were castrated, thin lips, but with two vivid eyes, as at first sight, I did not know well whether they were the expression of an alcoholic or an intelligent man! I later found out he had both.

In the conversation I found out that his name was Abdyl Haki Kuçi. From the expressions it was understood that he was from Kuçi i Kurveleshit. I had seen with my own eyes the tortures I inflicted on the body of one of my cousins, because of me. There was bleeding, crushing and scratching of the flesh in three or four places on the body.

All this was presented to my eyes with the clarity of the photograph, when I had the torturer in front of me and it seemed to me that he was sharpening the machete to start working on me as well, as seen in the movies. But he started the conversation very gently, he asked me about my studies, about my career, about the functions I had, to which I answered clearly, why they were familiar things and I had no reason to hide them, nor to seek to soften or change them.

I had complete accuracy that I had not committed any action to the detriment of the country, nor of the people, and even whenever the opportunity presented itself to me, I tried to be honest with everyone.

Within a few days, we were able to complete the minutes, which the investigators found sufficient to justify his investigative work. I signed this minute without difficulty and without any physical restraint. Only once during this record did we get heated up in conversation and the investigator, in a moment of nervousness, gripped a whip in his hand and tried hard on the table.

I thought the investigation was over and so I started to sit quietly in the cell. To pass the investigation without torture in that period, was impossible.

Did this luck belong to me? Would they keep their word to me when I surrendered that I would not be tortured? It still seemed impossible to me! These bluejsha in mind in those wet and cold days of January 1947. Cell life, grave life, our fear and boredom! In those days we began to see people in panties, standing with their faces against the wall at the end of the corridor, between the door of our cell and the door.

The first we heard about was Shefik Kondi, a tyrant, an old man and a wise and humorous man. The cellmates told me that they had put him there at the end of the corridor before and that in a moment of crisis, caused by fatigue, he had opened all kinds of cells and shouted: “Get out!”

The other friend who was added to Shefik was Dom Shtjefën Kurti, also with short panties on his feet and a face against the wall. From time to time, others were added and subtracted, so that we could not learn their name. Every time I went in and out of the cell, I did not look at them, because I felt bad. To see two people, two to know each other in suffering and not being able to come to their aid! But it was even less horrible when at night I felt that they, from fatigue and sleep, fell to the ground with a whimper and your guards fell with sticks, shouting: “Get up, get up, you bastard!”

From there in the last days of January, the investigator called me again. He started telling me that we had to go through a new process, because what we had done was not accepted by the Security Directorate. “And of course, I did not accept it either”, added the investigator, “why in the flames of the ball, you come out unscathed”. I replied at once that I had nothing to say or add. The investigator then told me that the Security Directorate wanted to know:

- Who were the spies of the Ministry of Internal Affairs?

- How were decisions made for the executions of February 4 and February 28, 1944?

- With whom did I have contact during the time I had been on the run?

From the type of cases and from the tone of the investigator, I understood that he would also seek torture, to have the result he wanted. And after the third point would implicate my brother, Kelly, who had beaten me, I decided to take a completely negative attitude, not only not to implicate other people, which I had thought about myself since I surrendered, but also not to blame myself without guilt, and to escape torture.

When I got back to the cell, I briefly told my friends how things were with the investigator. Betti, the Italian who had a longer internship with investigators, told me openly that a long period of torture would begin. It was clear that I had no option for any relief mitigation measures; the only thing I could try, was to dress as thickly as possible, with the minimal hope of not being stripped. For this I added a sweater and put it on for meat, under the shirt. Of course, that night I slept little or not at all.

However, the next day, when the day dawned, a gloomy, cold and wet day like all that winter of 1946-1947, I felt morally strong enough to withstand any torture, and not to take no man by the neck. Only for this I prayed to God, and for myself, even death did not scare me, I even thought of it as a lucky solution.

When he called me, as usual in the guard captain’s room, the investigator was very grim. He began to tell me that he knew well the organization of the Ministry of Interior and the ways and means by which the people were oppressed before the liberation, to let them know that the means they used to expose the neo-communists and their actions was to activate spies.

He also asked me who entered and who left the Ministry. I replied that I could not know this, since I had my own office and I was not interested in knowing such a thing; but when the angry investigator insisted on knowing who I had found in the Minister’s office every time I entered, I replied that I had found Hysni Dema, the Commander-in-Chief of the Gendarmerie, Tahir Kolgjini, the General Director of Police, among others. privately, I had once found Beqir Valter, who had been convicted by a special court and executed.

The investigator went back to the spy case, when he saw that I was insisting on the explanations given, he got nervous and told me to take off my coat and sweater, and left me with only my shirt. He took me out into the corridor and called the guard named Vani, and told him to leave me at the end of the corridor, where there were three others. The guard then said something in the investigator’s ear. He replied, “Go to the bathroom.” He came himself and after leaving me there said to me: “stay here and think”.

I guessed that the guard would have told him that among the three who were standing at the end of the corridor, was Dom Shtjefën Kurti. And since I was a Catholic like him, the guard could go among me, who knows what plots we could plot. Of course, the guards inadvertently did a good thing, that in the toilet I was not under his watch, and that I could lean against the wall or sit down. The door was locked and like all cells, there was a small counter that the guard opened whenever he wanted to see what was going on in the bathroom. From the counter alone, it formed one as the entrance to that narrow corridor.

Once all the toilets were behind the doors and after they were removed only the frames were left. So, when four people went, the others waited in the corridor, of course with their backs to the actions of their friends, and often closed their noses and ears.

As soon as the investigating captain and the guard closed the door and told me to stay there, I opened my ears to see if anyone was in the bathroom. I immediately realized that someone in deep silence was breathing. But who was it? Someone like me or a guard for their own needs. I waited and after a while when I made sure there was no guard near the door, I stretched my head to see who it was.

At the end of the corridor hung by boat chains on the window bars, was a tall man. I knew him after he had been a driver at the Ministry of Justice, with the surname, Stërmasi. He opened his eyes and he recognized me. More with signs than with words. He showed the wonder he was seeing me there and I said:

- Can I help you?

- “No,” he said, “you have nothing to do, for I have been here for a few days.

It was seen that he was very tired and wanted to sleep. Meanwhile, a young boy with bare feet in cement came out of the toilet. His name was Emin Bakalli, the brother of Dr. Bakalli. He had been to Fulc school and that was enough to understand why you were there. He told me that in the other toilet, there was Panajot Zbogi, a Himarjot with a dynamic type. These were acquaintances with fellow torturers.

Shortly before noon, the guard came and gave a loaf to Zbog’s Grocery. The grocer offered me half of it, but I refused, telling him I was not hungry. After noon we were taken out of the bathroom and dispersed to other cells. They left me in the corridor and threw a blanket over my body. Although it was heavy, it warmed me up. That January day was cold and I feel it a lot.

Of course, the guards do not do this to me for good, but for “revolutionary vigilance”, so that the other prisoners do not recognize me when they go to the toilet. Certainly, such were the orders of the investigators. In this position I stayed for three hours until all the prisoners in the bathroom finished their work. Then the fourth one took us back to our assigned places and we stayed there all night.

When I thought of Stërmas being crucified like Christ and Bakalli barefoot on cement, I felt privileged. I started to feel tired and from time to time I lay down but always after noticing the steps of the guard he would not come and see us lying down.

At four o’clock they took us back to the toilet. This time they shot me and me in my cell. He was now a less vigilant guard. I managed to get into the mattress and sleep and those hours passed quickly.

When the guard came to take me to the place of torture, he saw me lying down and said to me: “Even if you cover yourself under clothes”?! And he shot me with the broom they had brought to clean the cell. I found the three dangerous ones there, it was a very melancholy return.

One by one the torture comrades called the investigators and sent them back there. After them they called me too. The investigator would ask me, and when I did not answer him as he wished, he would punch and kick me, telling me that I was a sworn enemy. Luckily for me, this was Abdyl Haki Kuçi, the small investigative captain and seemingly with tuberculosis and powerless to hit me hard. So, his kicks only had an effect on me warmer. /Memorie.al

Continues in the next issue