By Besnik Dizdari

Part Two

Memorie.al / As I wrote some time ago, I have been recently struck by the publication in Italy of a book about “Spartak” Moscow by the Italian author, Mario Alessandro Curletto. I got the book, read it, and was shaken to learn how the Stalinist regime had treated the protagonists of this football team that became legendary. Thus, I am moved to publish this series from the book, because many “Spartakist” events, directly or indirectly, also concern Albania. I contacted the author. I told him that Albania has played 11 matches with “Spartak” Moscow – perhaps a European record for the history of “Spartak” itself. The author of the book, with the sincerity of an honest and inquisitive historian, became very curious to know about these matches and the so unusual relationship between “Spartak” and Albania.

Continued from the previous issue

Let us leave the floor to Curletto’s book.

“Red Square”

MARIO ALESSANDRO CURLETTO

From the book “Spartak Mosca”

… Born only a year prior, “Spartak” suddenly achieves a sensational success in terms of prestige and appearance, as one might say today. On July 6, 1936, the Day of Physical Culture was celebrated with a parade in Red Square. Alexander Kosarev, president of the government commission for the event in question, as well as secretary of the Komsomol, came up with the idea of including a demonstration football match in the program, to be performed by “Spartak,” the club linked specifically to the Komsomol.

The proposal sparked a certain irony and criticism among the city’s party leaders. How could football be played on the cobblestones of Red Square? What if the ball hit an esteemed spectator?! Yes, because the nation’s leaders – including him, Comrade Stalin personally – might come to the Lenin Mausoleum for the festivities.

The most serious and concrete issue was creating a suitable terrain for playing football. After long discussions, it was decided to manufacture a massive carpet made of felt and wool fibers on top (10,000 square meters), large enough to cover the entirety of Red Square – from Saint Basil’s Cathedral to the Historical Museum, and from the guest tribune under the Kremlin walls to the GUM department store. Thus began what Nikolai Starostin termed the “Epic of the Carpet”:

“At night, when the square was cleared of vehicular traffic, about three hundred Spartak athletes – from children to its most prominent figures – armed themselves with leather sewing needles and dozens of meters of strong twine each; sitting on their knees, they sewed the pieces of felt together, one after another. By order of the authorities, shortly before dawn, the carpet had to be rolled up so as not to obstruct the passage of vehicles. Slowly and with difficulty, however, the work progressed.”

But the sewn pieces of carpet had to be painted green so that the playing field would take on a natural appearance; yet the firefighters intervened, blocking the entire operation to stop the risk because, during the hot hours of the day, high temperatures inside the carpet could cause the varnish layers used to spontaneously combust.

On the eve of the long-awaited day, while the Spartak athletes were finishing the pitch markings and Nikolai Starostin was directing the works, Alexander Kosarev (secretary of the Komsomol) approached, accompanied by two unknown military officers who were officials of the NKVD (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs):

“Comrade Starostin,” one of the two spoke, “you haven’t considered that players might fall and be seriously injured, which could happen before the eyes of Comrade Stalin. This carpet does not save one from contusions. Through my boots, I feel stones beneath the carpet pieces; therefore, your carpet does not provide sufficient confidence. Football will not be included in the program.”

The second official affirmed the first, while Kosarev, with a lost and pained expression on his face, stood in stunned silence, unwilling to believe that so much hope and labor could be extinguished in an instant. Nikolai Starostin instinctively looked around, as if searching for any possible support. A short distance away, Aleksei Sidorov, a player from the reserve squad, was carefully marking the white penalty spot. Nikolai called out to him loudly, not yet knowing what he would say, but as the player approached, a sudden thought struck him, and he commanded:

-“Throw yourself to the ground!”

One could only imagine what Sidorov thought at that moment, but the fact remains that, following the order, he jumped and threw himself down twice like a spring.

-“Are you hurt?”

-“What are you saying, Nikolai Petrovich?! Do you want me to jump again?”

At this moment, Kosarev intervened:

-“Why? It is now clear that the carpet is not dangerous. The game can proceed.”

According to Nikolai Starostin, who recounted this episode in his memoirs, a day after this jump on the improvised carpet, Sidorov suddenly developed a severe hematoma on one of his thighs!

This final attempt at “sabotage” had at least one merit: it allowed one to understand who stood behind all these bureaucratic obstacles that “Spartak” had encountered in organizing the long-desired event. It was understood that everything originated from the heads of the NKVD, to which “Dinamo” belonged – a club that, in its thirteen years of existence, had been surrounded by success but had never managed to secure such an alluring public role from the party-state.

In 1936, the position of Kosarev, a supporter of “Spartak,” was so clear that even the NKVD could no longer attack him head-on. However, the balance of power would soon shift. In this instance, it was entirely clear that the rivalry between “Dinamo” and “Spartak” had irreversibly crossed the boundaries of a mere sporting competition.

Despite the anxiety over the difficult preparation problems, on July 6, the demonstration match in Red Square took the stage. Facing each other were the first and second teams of “Spartak.” The public had the impression they were witnessing a friendly match played within an extraordinary setting. In truth, it was a football performance where exactly every minute of play corresponded to a highly studied choreography.

The number and manner of the goals scored were carefully programmed to transmit to the spectators – and specifically to the “Supreme Chairman” – the most spectacular actions as examples of a football game: goals were scored from free kicks, penalties, headers, long shots, and so on. The second half was supposed to be played for exactly 30 minutes, but if Stalin were to show signs of boredom, Kosarev, who sat beside the “best friend of athletes” on the tribune of the Lenin Mausoleum, would notify Nikolai Starostin ahead of time by pulling out a white handkerchief – and thus, the spectacle would stop immediately.

Precisely for this reason, during the predetermined half-hour, Nikolai fixed his gaze intently on the tribune, initially very anxious, then increasingly confident, as the minutes passed without the fatal handkerchief appearing. However, an event occurred that the meticulous organization had not foreseen: Stalin showed such great interest that even when the 43rd minute arrived, he forced the footballer-actors into 13 extra minutes of play, interpreting their roles as if in a theater, applauded by an enthusiastic and somewhat naive public unaware of the behind-the-scenes machinations.

For the role of the event’s director, a professional was aptly chosen: Valentin Pluchek, who would later lead the famous Theater of Satire, but who at that time was going through very hard times. Throughout his life, whenever Pluchek met Nikolai Starostin, he never failed to thank him publicly for changing his life by providing a valuable contract and a relatively high reward of 5,000 rubles. Yet, at these constant repetitions of gratitude, Nikolai Starostin always felt uneasy.

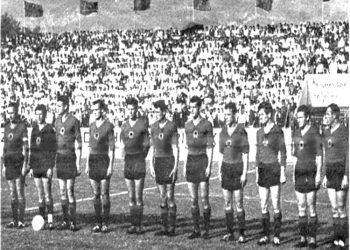

The second half of 1936 brought the players of “Spartak” the greatest success they could achieve on the field: the gold medal as champions of the USSR. In this autumn tournament, the last week’s match, “CSKA” vs. “Spartak,” entered Russian football legend. Played in Sokolniki, at the small stadium of the “Red Army” club, it was packed with 10,000 spectators. The playing field was surrounded on all sides by a wall of spectators who, from time to time, would surge forward past the white lines; during the second half, they even broke one of the goalposts. The match was halted to resolve the situation, after which everything resumed without disorder and with a happy ending: “Spartak” had won 3-1.

Using an objective expression, it must be emphasized that the newly begun march of “Spartak” would soon become synonymous with a success that appealed to a segment of the public across an almost incomparable spectrum: on one hand, it had captured Stalin’s attention with football – something the “fortunate” Dinamo had not achieved in all its 13 years of “honorable service” – and on the other, “Spartak” had won over the Moscovite working class (and beyond), which stood distant from the oppressive apparatuses of power; and finally, it had completed its circle by finding true, deeply devoted fans within the world of culture, art, and entertainment.

“In those years, the ‘National’ cafe, a kind of club for the creative ‘intelligentsia,’ daily hosted writers, artists, painters, and athletes; they would have a coffee and discuss a newly published book or the latest stage play,” recalls Andrei Starostin. He cites several of his conversation companions, seated together at a table by the window: the writer Yuri Karlovich Olesha, the Moscow Art Theatre actor Mikhail Yanshin, and the director Arnold d’Arnold.

Andrei had the reputation of an “erudite,” and stories circulated about him that was entirely different from the typical portrait of a footballer. It was told, for example, that during a “Spartak” match in Tbilisi, he had purchased several volumes of the pre-Revolutionary encyclopedic dictionary, the Brockhaus–Efron, at an antiquarian bookstore. Throughout the return journey to Moscow (about four days by train), he was immersed in reading them with absolute speed, as if he held one of the most passionate novels in his hands.

He was always an excellent interlocutor, perfectly integrated as an equal within intellectual and artistic circles. An old friendship bound him to the Moscow Art Theatre actor, Mikhail Yanshin: the two had known each other and been friends since childhood, yet out of delicacy, they addressed each other with the formal “you” (ju/vy). They spoke to his brother, Nikolai, with great passion and warmth while defending their views.

The character of Alexander was entirely different: patient, smiling, and very skilled at finding the right quip to de-dramatize any situation. The writer Lev Kassil, another “follower” of “Spartak,” defined him as one of the most knowledgeable and educated footballers among all the greats of the era, completely immune to the narrow interests that often consumed high-level athletes…!/Memorie.al