By Pierre-Pandeli Simsia

Memorie.al / On July 4, 1979, in Kuçovë (“Stalin City”), a shocking and painful event occurred that shook the entire opinion of that city. In the city’s cinema hall, residents had gathered, according to the announcement, for a meeting. In the most treacherous and shameless manner, during the meeting, citizen Zef Lekaj, an artist, composer, and poet, was arrested on the charge of “Agitation and propaganda against the people’s power”! I had the good fortune to see and hear up close the talented composer and poet Zef Lekaj, in his references to musical creations, creators, and young talents…! I was also fortunate to get to know his son, the talented musician, as well as his father, Sokol Lekaj, who accompanied me on the accordion while I sang.

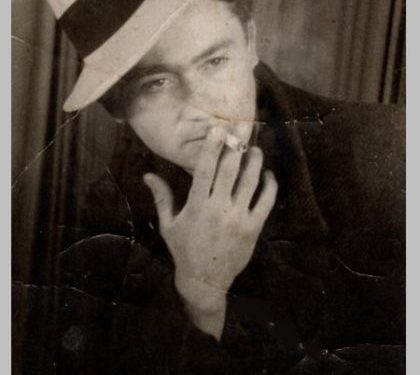

Even though those distant years are long gone, and I was in my adolescence at that time, I still keep in my memory the warm conversation and the voice of the artist Zef Lekaj. A wise man, a giant in appearance, cheerful, very friendly with everyone, an honest man, respected by all, a devoted husband, and an exemplary father.

The talented and unfortunate artist, who at the peak of his musical creativity was not only condemned by the communists and the party they served but was also unjustly discredited. (With the greatest shamelessness and baseness, Artist Zef Lekaj was arrested at the neighborhood People’s Council meeting…).

Every time we heard the voices of presenters at various concerts, at regional festivals and national festivals of our folk music, when they mentioned the title of the song and its authors: “The lyrics and music by Zef Lekaj, singing…”! Among the numerous creations of children’s songs, light music, and folk music, today, even though many years have passed, we all remember the song “The Little Lamb,” a production of the talented master, Zef Lekaj.

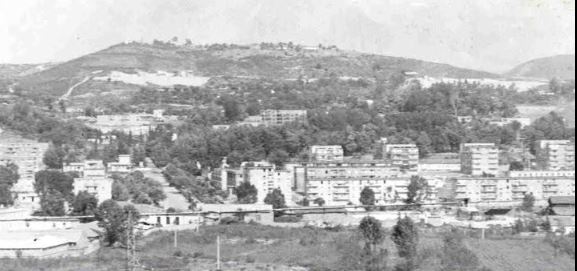

The city of Kuçovë (which was called “Stalin City” before the ’90s) was fortunate to have within its midst a talented artist born for art, to create music, songs, etc., Zef Lekaj. The party and the communists, together, in the mid-‘70s, condemned and imprisoned Zef Lekaj at that time, the next innocent victim of Albanian art, and together with Zef, the city of Kuçovë was also condemned, and once again Albanian Culture and Art were condemned.

It was the unfortunate fate of artist Zef Lekaj and his family to fall victim to the innocent madness of the unruly Albanian communism. For the years that Zef and his family lived in Kuçovë and contributed greatly to the art and culture of that city, they deserve honor and respect…! In memory of the life, creativity, and spirit of artist Zef Lekaj, I thought to have a conversation in the form of an interview with his son, Mr. Leon Lekaj.

Mr. Leon! You are one of the children of artist Zef Lekaj. Since you are also the author of the monograph about him, (“An Artist Under Crossed Pentagrams”), could you please talk a little more about his childhood and his formation as an artist?

It is a short question, but it requires a large volume of response. There are three names that, in my opinion, changed the course of his life as an artist. Dom Ndre Mjeda, who enrolled him at the Saverian College, a school for which the American scholar Edwin Jacques, in his well-known book “The History of the Albanian People from Antiquity to the Present Day,” would express: “…ten years before the first Albanian school of Korçë, there was also a prominent center for higher education in the city of Shkodër, the college of Saint Francis of Assisi, which provided technical and commercial education for around 400 students…”

At Kornolo, an excellent pianist and educator. From him, my father Zefi learned Gregorian music, as well as from fratel Buiati, a former violinist of La Scala in Milan, from whom my father learned solfège, harmony, counterpoint, and fugue. During these years, he often found himself in a dilemma of choice, as he wrote in his youthful diary, questioning who he would travel alongside; “…Dante, Shakespeare, Petrarch, Manxoni, Mjeda, or with Beethoven, Mozart, Verdi…”, and he answers: “…I love both sounds and verses.”

How did Zef Leka find the years after liberation?

– Like a captive! My father never believed in communism, even though he came from a poor background. In 1946, he participated in the uprising of Postribë, the first anti-communist movement in Eastern Europe, which was compromised, betrayed, and the consequences are well known. His brother Gjoni was initially sentenced as a member of the uprising, and under these conditions, my father fled across the border into Montenegro. There, he was forced to hide for thirteen months in a grave, because at that time, Enver Hoxha and Josip Broz Tito were in a “honeymoon” period, and from that moment forward, he was pursued on both sides of the border.

How do you remember your early years in a family with an artistic and musical father?

Not very easy. At that time, my father worked at the “Heronjtë e Vigut” Youth Club, which was adjacent to the Franciscan Church. It was a time when every movement of intellectuals was monitored, because the iron hand of the dictatorship was preparing to eradicate any kind of belief and elevate the faith in dictator Enver Hoxha to a god-like level. Even as children, we felt that kind of oppression because my father often asked us: – “Did anyone see you when you entered the church?”

Later, when we moved to Kuçovë, the class struggle loomed over us. Imagine, for my sister to gain the right to study, she had to roam the fields of the surrounding villages in the madness of what was called a “stage.” While my desire for higher education was set aside because it was not looked upon favorably to have two such individuals in one family. What a vile time! It was difficult for my mother, who besides being the mother of five children of an artist, was also an ideal wife and travel companion of my father.

Was your father, Zefi, a believer?

Certainly! The foundation of his education was always based on his faith in God. At that time, my father had a serious relationship with a girl from a Muslim family (Fatbardha Jaho), but this did not stop him from celebrating his marriage in the Catholic Church in 1952. Also, the way he managed to create a large family, with many children (five), while his artist friends were satisfied with one or two, points to this fact.

“Do not do to others what you would not want done to you,” is one of the maxims that guided him in life. Meanwhile, throughout his life, he worked with integrity, even though this kind of honesty, from dishonest people, turned into a trap for him, especially in the later years of his life.

Why did your family move to live in Kuçovë?

There were several reasons that forced my father to leave his beloved birthplace, Shkodër. The first was related to his past. My father had returned to Albania after an amnesty that the then government had proclaimed for participants in the Postribë Uprising. One amnesty was not enough for the communists to sleep peacefully. My father was being monitored. He felt this until the day they put the handcuffs on him. The second reason was economic. In Kuçovë, he was offered a higher salary as well as a job for his wife.

I think the third reason was that in his new workplace, he would have more freedom to implement what he had dreamed of over the years. Without anticipating that he would fall “from the rain into the hail,” he left Shkodër, not without pain, and accepted a proposal from the then Trade Unions to be appointed head of music in Kuçovë (formerly “Stalin City”).

During his stay in Kuçovë in the 1970s, your father Zef Lekaj experienced an explosion in his creativity. Where did the secret of this success lie?

I believe the essence of his success in those years lay in his past. From the age of sixteen, he managed to direct the school choir, which, it must be said, had quite high demands. Years of experience led him confidently and unshakably towards success, not only for himself personally but also for the artistic ensemble he directed.

Another equally important reason was his collaboration with amateurs, or as they were called at that time, “amateur groups.” There was an excellent relationship between him and the amateur groups. I would say without any hesitation that my father was adored by them, and at the same time, he respected them. Even in his darkest days, they would find a way and a hidden corner to secretly greet their master. At that time, this meant a lot.

With a rich career in his musical creativity, your father received several awards during those years. Could you mention some of his successes?

My father is widely known to the public as the author of the song “The Little Lamb,” but that song is just a small part of his success. I would like to list some songs that, unfortunately, even though they should have been in the prohibited archive, were erased by an order from above. Nevertheless, I must publicly acknowledge that my father is the author of the lyrics to one of the most famous songs in Albania, “When the Sun Sets” (1958), “Say It Don’t Prolong,” lyrics and music (winner of the second prize at the First Festival of Light Music held in Shkodër, Albania in 1962), “Happy Am I For You,” a wonderful aria beautifully sung by Luçie Miloti and Pjetër Gjergji.

During this time you mentioned, he also wrote many other songs such as; “We Are Oil Workers” (performed by the trio: Mula, Tukiçi, Gjoni), “Today is a Celebration, Dear Homeland,” sung by Ramiz Kovaçi on Radio Tirana, “Good Morning Oil Workers,” with lyrics by Pal Nikolla, “This Song Rings Free,” performed in the Radio Tirana survey, December 1965 – January 1966, “Ardiana,” an emotional love song, winner of the First Prize at the Festival of Oil Workers, “Friends Are Waiting For Us” and “Safe Flight,” sung by Frosina Vasili, “Forward Oil Workers” – complex for men, first prize, “To Albanian Mothers,” 1973, “Fathers,” with lyrics by Dritëro Agolli, sung by Ruzhdi Karaj, songs that received national and local recognition at children’s festivals, and many others, culminating in the maximum recognition given in April 1969 to the ensemble of the Palace of Culture of Kuçovë, directed by him, with “The Festival Flag,” surpassing distinguished names of ensembles of that time.

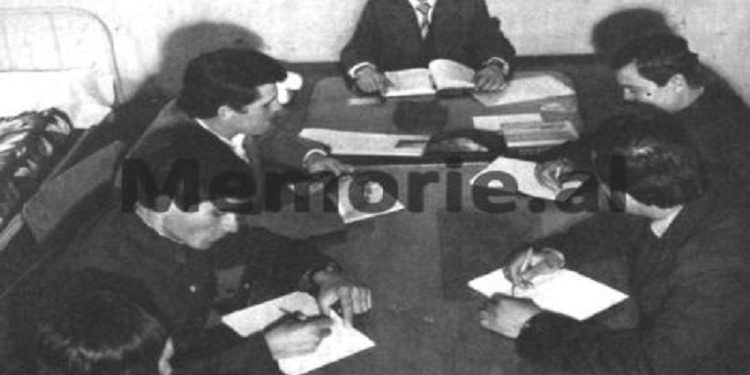

At the peak of his musical creative success, in the late ’70s, a painful event occurred that completely changed the lives of your entire family. How do you view today the arrest of your father, Zef Lekaj?

Certainly, as a delayed move by the regime of that time. I remember that until 1979, all his schoolmates had met bitter fates. They had either been executed, fled, or were sentenced to prison and internment. It was a stricter strategy than that pursued by the State Security against the American Technical School led by Harry Fultz. My father was “the last of the Mohicans.”

It was a move that shocked an entire city, a large society. I will share just a part of his diary describing that day. “…The jeep was headed to the Internal Affairs Department of Kuçovë, and the man who had put the handcuffs on me asked with irony:

– ‘Hey, you arrogant one, how do you like this job? Perhaps you didn’t know that this arrogance has brought you to this door? You never greeted me when you saw me on the street.’

– ‘I’m sorry,’ I said, ‘I don’t know you, who are you?!’

– ‘How is it possible that you do not know the zone operative? – he said, and then added, – it doesn’t matter, it’s good that you recognized me now, who I am.’

And with arrogance, like a triumphantly victorious man, he entered the Internal Affairs Department.

An hour later, they sent me to the prison in Berat.

What crime had I committed that I did not recognize the zone operative?!”

Everything happened just three days before his retirement. I believe it would be futile to comment on this fact.

Do you remember if your father expressed dissatisfaction at that time within the family against the communist regime?

Yes, he expressed it regularly. My father was not one of those who were fed with the empty spoon of communist propaganda. Being an excellent speaker of the Italian language, he kept regular ties with what was happening in the world. In fact, I remember one day he was summoned to the Party Committee because he had announced the news of the invasion of Czechoslovakia before the official propaganda could do so. I, perhaps more than my brothers and sisters, had the chance to debate. But today I say with complete confidence, few knew how to dot the “i’s” of communism like he did.

It is already known that arrests with such charges had serious consequences for family members. What happened to your family after your father’s arrest?

We have to consider ourselves fortunate that the decision for internment had been lifted a short time before, but even so, we were almost interned, isolated, and lonely. The first to experience the “whip” of the dictatorship was my mother. From an economist, she was made a cleaner working three shifts. This was followed by my sister, who, despite being an excellent student, was expelled from the university, and then there was me, who was just waiting for an appointment as a music teacher, but they “gifted” me a new appointment as a worker in the stone quarry at Ura Vajgurore.

After the ’90s, when communism began to fall in Albania, what was the fate of the family of artist Zef Lekaj?

It was the same fate that befell the friends of honest people like him. With his initiative, along with the help of his friend, Gjosho Vasija, he returned to his homeland. Until 1992, he managed to settle his large family in Shkodër. We, his children, weary from political and economic persecution, which was the practice of the communist system, all arrived in our hometown with our hands in our pockets but intoxicated with freedom and thirsty for knowledge and culture. But that was not enough. None of his children, and much less he himself, knew how to scream and shout about the injustices done to them by the communist system. Thus, we had to pay the price of integrity with forgetfulness.

What is the relationship between literature and music in Zef Lekaj?

If you closely follow my father’s songs, you will see that most of the lyrics are his. Take a look at the song, “When the Sun Sets”! It was written in 1958, at the request of the music author, Leonard Deda, and I challenge you (beyond modesty here) to find a similar lyric in those years. As someone with a good understanding of music and literature, he knew, like few others, that for a text to be set to music, it requires rhythm, musicality, and adaptability. These are two arts that intertwine only when you know them well.

Has he and your family been compensated for the sufferings of the years in political prison?

He himself did not enjoy anything. Up to now, apart from the propaganda of the ruling party, we have only received a payment of eight million lek (old currency) during the time when the democrats were in power.

Is there any recognition of your father in the years of democracy?

In 1995, Zef Lekaj was decorated by the President of the Republic (Prof. Dr. Sali Berisha) with the title “Torchbearer of Democracy.” On the occasion of the 75th anniversary of his birth (post-mortem), on October 16, 1999, the Municipality of Shkodër honored him with the title “Pride of the City,” while five years later, the Municipality of Kuçovë gave him the title “Honorary Citizen.” /Memorie.al