Memorie.al / The distinguished striker of “Flamurtari” Vlorë, the man who brought to their knees the long line of Albanian goalkeepers of the 1980s, as well as international legends like Zubizarreta (the legendary goalkeeper of Barcelona and the Spanish national team), is named Vasil Ruci. Born on February 17, 1958, in the “Vreneze” neighborhood of Vlorë, he remains an elite figure in Albanian sports history.

Mr. Ruci, how did you find your way into sports?

Football is compared to art because of its beauty. All those dreams crystallized in a single day. A friend took me to the “Pioneer’s House” and handed me over to Skënder Ibrahimi. “Try this one too,” he said. He gave me a jersey. “Go in,” he told me, “and don’t be afraid.” I had dreamed of becoming a footballer. In one day, I found myself among those who would become the stars of football: Perlat Musta, Kreshnik Çipi, Hasan Lika, Kokalari, Kristaq Mile, Emil Kërçiç, Halit Gega, Agron Dauti, and others.

It was a Spartakiad where the best were announced. We had been losing. We were trembling during the break – actually, we were crying – but when we went back in, we won 3–1. That’s how I became a protagonist for the youth team. After two years there, around ages 15–17, I moved up. I remember in one championship, I scored 14 goals. For a striker, goals are the epicenter of existence. I started in the midfield, but eventually, I found my place as a striker for “Flamurtari.”

When was your first appearance for the “Flamurtari” senior attack?

With the help of Bejkush Birçe, I played my first match in 1976 against “Besa” of Kavaja. I scored a goal that made me shake with emotion. I penetrated an attack line made of legendary names in Vlorë football: Shkëlqim Zilja, Spiro Çurri, and Pano Xhaho. I remember a cold day before training when the coach told Agron Sulo, a potent striker who had seen a decline that he would be on the bench. “If I stay on the bench, I’ll leave for good,” the great Agron said. He left that day, only to return in 1978 as a coach.

What happened next?

The 1980s would be considered a qualitative leap for “Flamurtari.” No one could have predicted then how much this team would be loved – adored for the goals, the “dance” on the pitch, and the results.

How was this achieved?

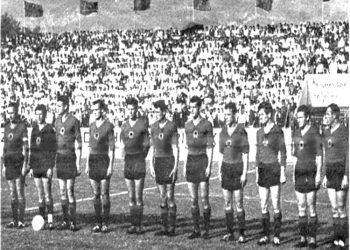

Other city teams were similar in how they played, won, or lost. At that time, there were “rebel” teams that would win one match and lose twenty. Unable to break Tirana’s dominance for a long time, we eventually blocked them. Tirana had two shining strikers: Agustin Kola and Arben Minga. Today, those players are scattered, but our 1980s team was a dignified squad: Petro Ruci, Fred Zijai, Edmond Liçaj, Agim Canaj, Kreshnik Çipi, Shkëlqim Zilja, Pano Xhaho, Rrapo Taho, and others. Alongside them came the “class of 1960”: Fred Ferko, Agim Bubeqi, Gjondeda, and Memushi. The journey looked like this: 1982–’83 runners-up; ’83 and ’84 finalists; 1985–’86 winners. We touched two cups. Unfortunately, we finished as runners-up six times. Tirana held the weight then, with defenders who were hard to penetrate: Tur Lekbello, Arjan Bimo, Skënder Hodja, Millan Baçi, Besim Vladi, and others. It was the era of Tirana’s “star” athletes.

What was “Flamurtari’s” performance in Europe?

That era also forms a long chain of pain regarding my non-participation with the team in the Balkan Cups. For the first time, the team traveled to play AEK Athens and Velež Mostar (in former Yugoslavia). I was not allowed to participate in either match; I was turned into a simple spectator suffering the tragedy of his people – I was suffering because of my “biography” (political background). Agron Sulo told me: “Vasil, go fix your biography in Dhërmi and then come back.” The team left, and in my place, they took others.

What impressions do you have from the matches against the great ‘Barcelona’?

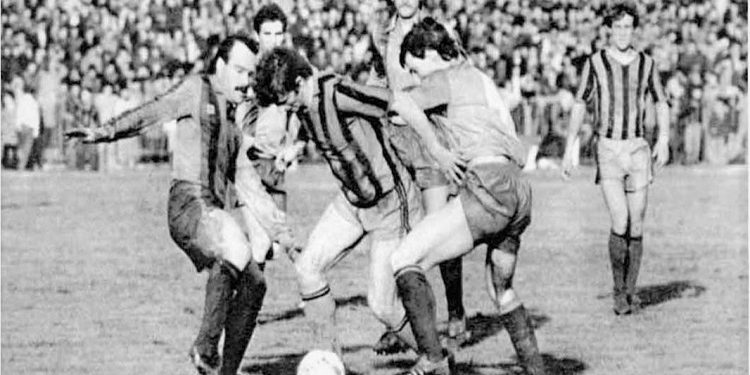

At that time, ‘Barcelona’ was a massive name in European football and came to play against us with all its authority. They had collected endless titles in Spain and Europe. Barcelona arrived in Vlorë in September for the first round of the European Cups. Their lineup was full of stars.

In goal was Zubizarreta, who was also Spain’s national goalkeeper; Gary Lineker, the star of the English national team and a renowned goalscorer; and his compatriot Hughes. There were Spanish internationals like Carrasco, Alberto, Miguel, Victor, and others.

Everyone has asked me over the years: “How did you score the goal?” I’ll summarize it: a ball came from the midfield, I stopped it and fired. I kept the vision of the goal even when my eyes couldn’t see it. Zubizarreta, an amazing goalkeeper, couldn’t save it despite his movements. The fury of the shot was immense; within seconds, the ball rested in the net, shaking Zubizarreta. It was a unique goal against a unique goalkeeper, who was considered the best in Europe. Barcelona was baffled but recovered and penalized us with a goal.

It is said that after that match, you were called the “team of the poor” that beat the “team of billionaires”?

When we arrived at the “Camp Nou,” it felt cold to us. You could hear the roar from afar; compared to our small stadiums, it was imposing. We finished as equals with Barcelona. We faced them in 1986–’87, and the balance was: one win for us, one win for Barcelona, and two draws. In the “Camp Nou,” through that noise, we heard shouts in Albanian for the first time. It was Kosovar boys scattered across Europe, calling us by name.

It has been said your team was heavily surveilled during these trips. Why?

Our team went to Barcelona without our goalkeeper, Luan Birçe. It was for the absurd reasons of his “biography.” He wasn’t allowed to play in either match. In fact, nearly 70% of the team was registered with “chills” – as the Vlorë people called a bad political biography. Many at “Flamurtari” suffered from this “chill”: Luan Birçe (until he was forced to leave), Fred Zijaj, Kreshnik Çipi, Fred Ferko, Vasil Bifsha, Agim Bubeqi, and I.

When we went abroad, people asked if our pay was 2 dollars. It was unimaginable. The press at the time wrote that the “team of the poor” beat the team of billionaires. On every trip, we were accompanied by “Party Commissars.” Before leaving, we were called to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and told: “Listen, they will throw dollars at your feet, but you must not accept them.”

How do you remember the match when you toppled “Partizan” Belgrade?

“Partizan” Belgrade at that time represented that somber part of the Balkans. In Vlorë, they found a team ready to “eat them alive.” The politics of the time considered it a political game. The situation in Albania was heated, but in Vlorë, it was several degrees hotter. People didn’t just talk about victory; wheat and corn were forgotten. All propaganda was directed at “Flamurtari.” The pressure was extraordinary. We won 2–0 in Vlorë with a goal by Iliadhi and an own goal. The temperature rose before we went to Belgrade.

Before crossing the border, they told us: “You must win because this is a political game.” In Belgrade, the situation was different; they saw it simply as a game. Sokol Kushta’s goal liberated us from two responsibilities: political and sporting. After the 72nd minute, our qualification was certain. We qualified even though we lost 2–1 in Belgrade. We toppled “Partizan,” which had stars like Smajić, Djurovski, and Katanec. The latter is now the coach of Slovenia.

What happened at Han i Hotit?

The trip back was by plane and bus. At Han i Hotit (the border crossing), we felt the state’s reprisal for the first time. Until then, it had been directed indirectly, but there we saw the true “face” of that state. As soon as we arrived, the customs officers were somber and told us that, by an order from above, the bus would be searched. Ferko shouted: “Get ready to strip; they have the handcuffs ready.” They took us off the bus and searched us by stripping us naked. They even dismantled the bus seats to check them.

They confiscated a television from Rrapo Taho, Fred Zijaj, Çipi, and me – televisions that had been gifted to us by Kosovars who had come to Belgrade to see the match. Meanwhile, the people of Shkodra welcomed us with flowers, blocking the bus to celebrate as if we were their own team.

Certain members of the Central Committee, who were fans of Tirana, sought to strike “Flamurtari” because they were jealous of its brilliance in Europe. Their anger manifested slowly. After returning from a match in Poland, half the squad was disqualified – Çipi, Taho, Ruci, and others. A journalist in the “Zëri i Popullit” newspaper wrote harsh criticisms against us.

After that, in an effort to damage us, they demanded we take the “3200-meter” physical test – a test I had never passed. So, with a broken heart, I abandoned the sport. In my 10-year career, I am the top Albanian goalscorer in European Cups: 6 goals in 12 matches. In Republic Cup finals, I scored 4 goals in 5 matches. I left the sport with a title everyone has: “Master of Sport.” / Memorie.al