By Bashkim Trenova

The twenty-first part

Memorie.al publishes the memoirs of the well-known journalist, publicist, translator, researcher, writer, playwright and diplomat, Bashkim Trenova, who after graduating from the Faculty of History and Philology of the State University of Tirana, in 1966 was appointed a journalist at Radio- Tirana in its Foreign Directorate, where he worked until 1975, when he was appointed as a journalist and head of the foreign editorial office of the newspaper ‘Zeri i Popullit’, a body of the Central Committee of the ALP. In the years 1984-1990, he served as chairman of the Publishing Branch in the General Directorate of State Archives and after the first free elections in Albania, in March 1991, he was appointed to the newspaper ‘Rilindja Demokratike’, initially as deputy / editor-in-chief and then its editor-in-chief, until 1994, when he was appointed to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs with the position of Press Director and spokesperson of that ministry. In 1997, Trenova was appointed Ambassador of Albania to the Kingdom of Belgium and to the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Unknown memories of Mr. Trenova, starting from the war period, his childhood, college years, professional career as a journalist and researcher at Radio Tirana, the newspaper ‘People’s Voice’ and the Central State Archive, where he served until the fall of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, a period of time when he in different circumstances met many of his colleagues, suckers of some of the ‘reactionary families’, etc., whom he described with a rare skill in a memoir book published in 2012, entitled ‘Enemies of the people’ and now brings them to the readers of Memorie.al

Continued from the previous issue

“Enemies of the people”

On internship for a communist in the Construction Vehicle Office

At the end of a year of work I did the blood tests together with the others. I did not do well. The doctor asked me to go to the hospital for treatment. I was hospitalized for the first and last time in my life in the hospital. In a room with me there were other beds, “loaded” with chrome, copper, zinc, carbon, etc. They were miners, who “represented” all the mines and all kinds of mineral reserves of the country. The mines were “displaced” in their lungs, blood and brains. The miners, as they marched in front of the tribune of the Party leadership on the occasion of May 1, were described as the “pride of pride” of the working class, as “its backbone”. They “broke the blockade” that the international bourgeoisie and the traitors of Marxism-Leninism sought to impose on Albania! They were the sure guarantee of victory and the defense of socialism. Slogans were not lacking. Places in hospitals, in the hallway of slow, indifferent death, were lacking. When you think then that Albanian miners, mostly of rural origin, felt “privileged” even though they knew the danger, but at least provided a salary that was vital to their family, provided the salary of mutilated life and certain death premature.

After I was released from the hospital, I was removed from the drummer’s ward and transferred to the motorcyclist’s ward. I did not want to leave the drummers. I was used to them and made friends with them, all ordinary people, Hallejians. Little by little, they had begun to talk to me about their troubles, not complaining, but as people seeking to share something of their own with a man, just as sharing a morsel of hunger, a human pain. In these conversations, among other things, I learned a lot about the life of Milto Mima.

Milto, the brother of the actor Prokop Mima, in the ranks of “enemies of the people”!

Milto was the master of everything. The workers themselves called him “master” and “boss” even though he was not the boss. They also called him “human soul” and such was Milto Mima. His name was associated with a number of innovations of the Construction Vehicle Office. Milto, however, was among the enemies of the regime, not that this was his choice, but he was Prokop Mima’s brother.

The regime had not forgiven Prokop for the fact that during the war years, he had been part of the youth of the National Front, a nationalist political organization opposed to communism. Procopius had another “weakness”, he had studied in the West. These were more than enough reasons for him to be arrested in 1945 and then sent as a soldier to the labor battalion ward. Young people who were considered opponents of the regime, or who came from families that were considered as such, were sent to this ward.

Prokop Mima managed to become one of the most important actors in the history of Albanian theater, a master of reciting the Albanian language. The dictatorship took “care” that his roles were generally of a negative nature and that he be evaluated by the public. The spectator knew how to appreciate this great artist. Milto also played a small role in a play staged by the amateur troupe of the Construction Vehicle Office, but he too was given a negative role, as was the case with his brother.

As a “soldier” of the Party I could not oppose the decision to move to the motor ward. I parted ways with drummers and started working at motorcyclists. The steam and acid fumes that covered the space of the drummer’s ward did not spare the workers of the other wards of the workshop, especially those of the electrical ward, which was very close, but also those of the motorists. No protective measures were intended as necessary, no simple aspirators or fans. The self-styled power of the working class, not only did not make the fortunes strong, but “took care” that the workers stay as far away from such problems as possible, isolating them in a total ignorance. Never, in any press body, on radio or television, in any scientific journal, have figures been published during the dictatorship, even if manipulated, to testify to accidents at work and death from these accidents or from inappropriate working conditions. In Party congresses and in the dictator’s speeches, this problem is non-existent even though it was endlessly said that “Man is the most precious capital!”

In the drum unit, we “removed” the deep cold of winter by approaching from time to time near the boiler where the lead was melting and extending our hands on it. In cold motors it penetrated deep into every cell of the body. A stove improvised from a barrel of gasoline stood in the middle of the ward to be lit only once in the morning for a few minutes and once again during the lunch break. The workers, even though they never managed to warm up, found reason to rejoice as if they were dealing with their stove, which had given them the difficult task of heating a “football field”. Such were the dimensions of the motorcycle ward and its annexes. Old boards of truck bodies were inserted into it to burn. The fire was ignited after it had been thrown inside a quantity of gasoline and cloths dampened with gasoline. Combustion of gasoline created a gas pressure, which exploded strongly throwing up the stove. This was the expected moment. Everyone burst into laughter taken. After that the work began. The wind was blowing from all sides. The windows, which replaced the space of a ward wall, were more without glass than with glass, somewhere with cardboard and somewhere with plywood.

For me, however, fate helped me. A worker, working in a dismantling sector near the motorcycle department, had improvised the same brazier from a truck differential. His name was Eshref. I’m not sure about the last name. It seems to me that Demner had it. He was from an old Tirana family and kept the dialect of origin. He was always sullen and rude. From time to time, Ashraf filled his “brazier” with charcoal and brought it to the place where I worked. I later learned that Ashraf was one of the declassed. Thus the language of the time was defined as those who had a commercial or, say, bourgeois origin. Like it or not, he was thus part of the “enemy” contingent of the class. Ashraf treated me like a good friend even though we never became friends. He was proud. He knew his place as well as why I had gone to the Construction Vehicle Office. Logically I was on the side of those who had declared him and his family as outcasts, which meant they were enemies.

During the three years that I stayed in the Construction Vehicle Office, I learned that there were quite a few among the workers like Milto Mima or Eshrefi. Among motorcyclists, another one, also called Eshref, was tainted in his biography. Such was Veliu. Both of these were skilled specialists and workers. The head of the ward always relied on their “readiness” when he raised sharp problems in the meetings of the staff, which encountered contradictions, such as that of the continuous increase of the rate at work. If the logic of the time were to be followed, they would have to be the first to oppose or sabotage an increase in rate and production. By this logic, not the enemies of the class, but the working class itself, united like a steel fist around the Party, had to be at the forefront with an ever-unprecedented enthusiasm. It was to be the sure support of the Party, and therefore of the increase of production and of labor rates. The reality was not like that. The enemies had to show their “zeal” at work, otherwise the dictatorship of the proletariat knew how to settle accounts with them. The weary working class, exhausted by poverty and hunger, did not have the strength to pursue the false socialist “enthusiasm”, to enjoy a fictitious reality, which did not cease to demand from it sacrifices and only sacrifices, saving everywhere and in everything, rule out endless hardships and deprivations.

Among the motorcyclists, in addition to the two Ashrafs and Veliu, there was another, a young boy with a few fallen hairs, shy blonde, who was part of the declassed. I do not remember his name. The surname was Llagami. He sometimes came to the lathe where I worked to show me the poems he had written that would never be published during the dictatorship. In its propaganda, the Labor Party strongly supported the talents of the working class, but according to her, not all workers were part of the working class. The descendants of the bourgeoisie had also become workers, but they always belonged to the bourgeois class even though this class was practically non-existent under socialism! About twenty-five years later, when communism was overthrown, the “bourgeois” worker Llagami came and met me in the editorial office of the newspaper “Rilindja Demokratike”. He looked happy, but did not make any enthusiastic statements, did not express any hatred, was as always reserved, shy even in his smile.

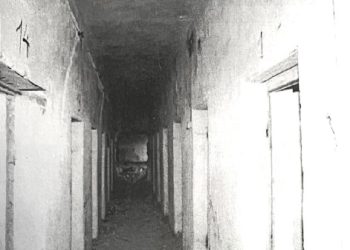

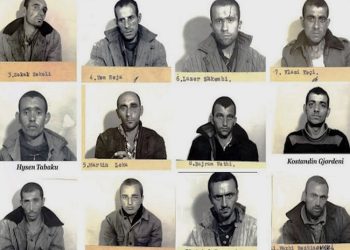

There were “enemies” and declassed in all wards. In the upholstery ward was Tixh. One of her brothers had fled abroad for years and had not become alive since. He was probably killed in an attempt to cross the state border. Çim Karapici was at the electrical department. In another ward was Xhafa. Neither Tixhja, nor Çimi, nor Xhafa had done anything to deserve to be classified as enemies. I was told about Xhafa that his brother was or had been imprisoned in Spaç prison and had taken part in a general revolt that took place there and that was brutally suppressed by the dictatorship. Hakiu and his brother, Bashkim Shala, were in the mechanical department. Later, as we were working to build a mansion with volunteer work, I saw an elderly man there; it looked like he was in his seventies. Wearing rubber boots he mixed sand and lime with his feet, occasionally adding water to the mixture. Others called him “Baca”. I learned that Baca was, if I am not mistaken, the uncle of Haki and Bashkim. He had just been released from prison where he had served his sentence as a nationalist, perhaps as a member or as a sympathizer of the National Front. After prison, Baca was married and had a baby. He still had the energy to live and not throw away the years he had left. He worked there in the hope that a small apartment would be given to his late family. Maybe Baca was also the “culprit” why Hakiu and Bashkimi were “affected”!

In the list of “affected” of the Construction Vehicle Office was also a mechanical engineer, Toni, it seems to me that his name was. He had a tribal connection, probably the grandson of a Catholic clergyman, Father Anton Harapi. The latter at the time of the German occupation of Albania, in September 1943, was appointed a member of the High Council of the Regency. After the war he tried to organize in the northern highlands a hotbed of resistance against communist rule. In June 1945 was arrested. By decision of 16 February 1946, he was convicted as a “war criminal” by a Special Court and executed as “an enemy of the people and a saboteur of power.” Tonini and no one even knew the grave of Anton Harapi, but he was asked to pay for it. I remember at a meeting of the Construction Vehicle Workshop Party organization, someone demanded that Tonini be fired because he was Anton Harapi’s nephew. This request was made after almost 30 years that Anton Harapi was executed and it was not known where his bones were lost. Tonini, perhaps, was not even born when Anton Harapi was convicted and executed.

I could go on to list those with “biographical stains” in the Construction Vehicle Office, but I did not know them all and I do not intend to give full statistics. Then, in a way, in what is common, in daily life, in dress, food, hardships, worries, strains I did not even see any difference between them and others. Poverty had the same face on everyone. Everyone came to work wrapping in a piece of newspaper, two large pieces of bread like two pieces of bricks. Inside them all shot either two or three fried peppers or a little cheese and one or two tomatoes, or an omelet or boiled egg. They all came to work wearing a pair of trousers that lasted several years or a dress or skirt that was painted, with patched socks and torn shoes that could not withstand the rain.

Everyone came back after tedious and poorly rewarded work in their apartments without space, without aesthetics, without heating and totally similar. Those with “biographical stains” were sure that the “stain” would not be removed even after death and would be inherited from their children and relatives from generation to generation. They were not sure how far the blow would go to them and when the next blow would be given, who it would hit today and who tomorrow. Others also knew that all of a sudden and regardless of themselves, one day they could become a “biography stain”. For this, a word, an anecdote, dissatisfaction or even a question like, for example: “how long will they be missing in the leek market”?! After all, everyone was exposed to the same pressure, confident in their economic, political and social insecurity. The communists of Oficina were no exception to this general.

With Kadri Roshi and Sulejman Dibra in the party internship at OAN!

At the Construction Vehicles Workshop I started my internship as a Labor Party candidate at the same time as Pjerin Vata, who was a work colleague of mine at Radio Tirana. A little later, Pranvera Nushi, a good, correct woman with a dental profession, as well as Sulejman Dibra and Kadri Roshi, both well-known actors of the Albanian theater and cinematography, came to do the same internship.

Kadri Roshi, in terms of internship, was and was not the same as the rest of us. Unlike us, who had never been communists before and expected to become communists, Kadri Roshi had been a communist. If we, from party candidates, were to become party members, Kadriu had turned from a party member into a party candidate, to become a party member again. If for us the internship was a test, for Kadri Roshin it was first a party punishment and then a test to repay this measure.

Kadri Roshi was a colossus of Albanian theater and cinematography. He started his career as an actor in the People’s Theater at the age of 21 being one of its creators. In the Theater he started as a prompter to become the absolute king of the stage. He counts about 180 roles on stage and in cinematography. He did not lack glory, nor did he lack poverty. Kadriu was honored with many high titles such as “People’s Artist” and “Honor of the Nation” and, as he himself said: “They call me ‘Honor of the Nation’, but I do not have a pocket in my pocket, I live on a pension that I do not care about water and lights … ”!

In a similar situation I met Kadri Roshin at the Construction Vehicles Workshop. They brought him there to punish him, to humiliate him, to ignore him, and perhaps even to forget him. Not even in the organization of the Party of the Office of Construction Vehicles and nowhere did I hear it said openly why Kadri Roshi was brought as a party candidate that is why a party measure was taken against him! He was said to have had a heated debate with a senior party official. Meanwhile, all sorts of unfavorable opinions about his character and morals spread. Despite them, in the Construction Vehicle Office, Kadriu was received by the workers and others with all the respect and love he deserved as a great artist.

Kadriu was assigned to work in the electrical department, which was opposite the drummers, where he occasionally came to meet Milto Mima and to warm his hands slightly in the lead-melting cauldron. During his stay in the Office he was paid as a beginner worker, as a trainee, that is, as in the first days of work of a 16-year-old worker, as an anonymous. The salary was not enough for the house or for him. The workers saw how the artist ate and shared with them their poverty, tomatoes and peppers. In poverty we were all equal, but if for themselves they accepted poverty as a “normal” abnormality, they could not accept that even the great artist, admired by them, was equal to them. Osman Gashi, the storekeeper of Oficina, after some time started working with two packages wrapped in newspaper. In one of them was the lunch prepared for Kadri Roshin.

Kadri Roshi’s vicissitudes in OAN, to exclude him from the party at all?

Even in this perpetual and general poverty we tried to find some pleasant hours, to have some fun. Usually, at the end of the fifteen days, when we also received our salary, we stayed in a small brewery somewhere near the Civil Hospital. Kadriu was everyone’s guest and the fun, the humor of the table. Only Rustem Habibi “competed” with him, a very charming worker, an inexhaustible source of gas with his every move and joke. Kadriu himself said that Rustem had a natural humor, while for he; he said that he wanted it; he played it to give us pleasure, to create a more pleasant environment. And what natural humor could Kadri Roshi has had, expelled from his “kingdom”, the theater stage, to connect and untie the red and blue threads of the electric mechanism of the trucks?! What natural humor could he have when he could not afford a glass of beer for himself or to offer a glass to friends?

Those who brought Kadri to the Office followed him here as well. As far as I can remember, there were two meetings of the Oficina Party organization, where he was asked to terminate his internship and be expelled from the Party as unworthy of being in its ranks. In one case I remember that Kadriu had gone fishing on the weekend and there he had forgotten about the fish, so one day he did not return to work. That was enough for him to go through the “scanner” in the Committee of the Party of the Region, to remind him that his biography was in danger of being blackened by an indelible “stain”. This “story” was closed because the Party was “generous” and Kadriu was once again given the opportunity to “correct” himself, to return to the right path! Something similar was repeated in another case. The party once again extended its “warm” hand to Kadri. He escaped expulsion from its ranks, which would be disastrous for him, his career as an artist and his family, not to mention that the Albanian theater itself would lose an irreplaceable colossus.

The great artist Kadri Roshi was not expelled from the Party. He continued his candidacy for a year and a half to become a member of the Labor Party. During this time he, with the amateur troupe of the Oficina Theater, staged two plays, “Fisheku në pajë”, by Fadil Kraja and “Commissar Memo”, by Dritero Agolli. In a way he was lucky enough to be brought to the Construction Vehicles Workshop, where director Agim Hysa and party secretary Sazan Qalliu were lovers of theater and art in general. They were the ones who gave the opportunity and created the conditions for Kadri Roshi to stage these two parts and, of course, to go on stage again himself.

In my life, “Fisheku në pajë” and “Commissar Memo” are two unforgettable and unique events. Kadri Roshi, while coming near the lead cauldron to the drummers to remove for a few minutes the cold from his delicate body, had “spotted” me as suitable to “engage” me in the body that would play “Bullet in the peace”. He entrusted me with the main role, that of Gjelosh Nika, a mountaineer with all his virtues and good or past habits. “Fisheku në pajë”, competed in the Amateur Theater Festival of the capital and won the flag of the Festival or, in other words, the first place. The Festival Jury honored me with the “Gold Medal”, while one or two others from our troupe honored them with silver medals.

The joy of everyone, of the “artist” workers: Agim Tabaku, Vaide Krasniqi, Engjëllushe Amataj, Dylbere Mejdani, Mihal Risto, of Cen, who with the power of a bulldozer and the accuracy of a computer, moved and raised the “walls” of the stage, was indescribable. The applause, the enthusiasm of the hall and ours, was accompanied, however, by a deep regret. We were instructed not to stay long on stage at the end to greet the audience; we were told that the curtain of the stage would be closed immediately. These precautions were taken not to give Kadri Roshi time as the director of the play to appear on stage, not to applaud him because a “convict” should not be applauded, because the applause could be interpreted as a disapproval of that that the Party had decided for Kadri Roshin! Kadriu silently swallowed this “surprise”, as I have seen him swallow, more than once, his tears.

Not many professional actors have had the honor and fortune to have a direct partner on stage Kadri Roshin. I am an amateur “actor”, in the second and last part where I played, I had this opportunity. After “Fisheku në pajë”, at the next Amateur Theater Festival of the capital, the amateur troupe of the Construction Vehicles Workshop appeared with “Commissar Memo” by Dritero Agolli. There were two main roles, that of Commander Rrapos and that of Commissar Memo. Kadriu played the role of Commander Rrapos and I played the role of Commissar Memo. As in “Fisheku në pajë”, but especially here in “Commissar Memo”, I have been left a deep impression by the iron artistic discipline of Kadri Roshi. In the rehearsals, just like on stage in front of the spectator, he was no longer Kadriu stubborn, rebellious, but the character in Kadriu’s soul and body. His only concern was that on stage never the commander, i.e. he in the role of commander, not to be in a position that would show him above the commissar, because the commissar was the Party. He was careful in how he approached the commissar even when he thought otherwise, careful to show that, after all, he should always listen to the commissar, i.e. the Party, its wisdom and justice! /Memorie.al

The next issue follows