By Albert Mayzie

Memorie.al /Only a great adventurer, a skilled cameraman, and a kayak sportsman, who, in his “brilliant” idea to travel four continents, couldn’t exclude Albania, could undertake a 60-day adventure across the country. Albert Mayzie, the last of the French travelers to visit Albania, accompanied by his wife and nine children, arrived in Albania for the first time in 1964. He stayed for almost a month. He lodged in various hotels across Albania, saw different tourist places, starting from Shkodra, Kruja, Tirana, Elbasani, Durrës, Berat, Korça, Vlora, Saranda, etc., and wrote about them.

In a memoir, covering the two months he spent in our country almost half a century ago, Albert Mayzie left us with a pleasant description of his adventure, but also an accurate and sincere image of Albania at that time. There are many parts of this picture that hurt us upon their recollection, just as there are things that evoke a kind of nostalgia.

This is the motif that runs through the book in the author’s impressions. He titled it simply “Adventure in Albania 1964” and then lists every movement, every detail. For the first time, this book is also available in Albanian from the “Migjeni” publishing house. His son, the ninth of his children, Alain Mayzie, was in Tirana during the promotion.

Passages from the book “Adventure in Albania 1964”

“Certainly not, and throughout the elaboration of this candid narrative, from a sincere friend of your country, you will feel all the criticisms that I intend to be constructive emerge. It is impossible not to feel certain dizziness after shaking off 200 years of oppression by foreign occupation.

Freedom, that dear word to the French, could only reach a country long suffering in slavery with a very legitimate kind of pride. But if the pride of being French has been tempered in me by the visits I have made to more than fifty foreign countries, I have felt myself blend with Albania in the shared love for the homeland, the only love that can later bring about the love for foreign countries.

Therefore, I hope that my readers can benefit from the magnanimity that the acquaintance of five continents has given us, and if this work ever falls under the eyes of Albanians, may they also be able to read in it, through my small jabs, the advice of a nagging old grandfather, but one full of good intentions,” he expresses.

“Sixty days trekking through Albania, observations, discussions, various reflections that allow me to give you an opinion from these first pages that we may understand each other well—it obligates only me, meaning a human being who can fundamentally make mistakes. Firstly, the Chinese presence is extremely limited in Albania. With the exception of military advisors (or their absence), it escapes the eye of tourists.

I speculate that we met most of the civilian advisors, since they were sheltered everywhere in the best hotel in the city, that is, in the same hotel as us. I cannot count more than two or three hundred divided across the fifteen main cities. They were always assigned a separate dining room, and only in Korça were we admitted to the same dining hall where they were; there were four of them in total. In Korça, some of them were helping to train Albanian artisans in the Chinese weaving technique; others in Shkodra seemed to be agricultural specialists, perhaps for land irrigation.

The presence of products imported from China is less limited: condensed milk, toilet paper, tea, umbrellas, trucks, electric lamps, vases, and tasteless pots, etc… Thus, a curious mixture of useful goods, especially trucks and condensed milk, and other completely useless goods, like vases, umbrellas, and tea. The consumption of this last item is extremely low; (Turkish) coffee is the preferred national drink. But above all, China is trying to replace the USSR (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) in the installation of several factories: spinning mills, chemical product and wood processing plants, etc., which will render great services to the country. But let’s leave Enver Hoxha and Mao Tse-tung to sit side-by-side on the walls and in the windows of bookstores; this has nothing to do with us.

We wish Albania to find its own path, and let us not imagine a yellow peril at our gates. This would mean going back a century, regenerating the mentality of our grandfathers, and only God knows where this led the world from 1870 to 1939.

From this first tour of the city of Shkodra, we had formed the opinion that the ‘most backward country in Europe,’ according to French school geography books, had clearly made very great progress. If it still had much to do, wouldn’t that only be to catch up with its neighbors? We would have to wait to pass from one surprise to another, from one contrast to another.

Indeed, when we returned from this very modern evening stroll, I saw groups of Highlanders in ancestral costumes pass under my windows, and then I noticed two terrible carts patched up with pieces of string and loaded with passengers. Not far from that spot, a truck that had stalled due to some damage was blocking a wide, almost deserted road. At the clock tower, an armed soldier stood vigilant (I ask why?), and several beautiful young garment workers in open summer dresses, holding each other by the pinky finger, were passing behind the statue of Stalin. We had there a very attractive brief summary of all of Albania, old and new, strained and relaxed, into whose depths we would now penetrate to know it better day by day.

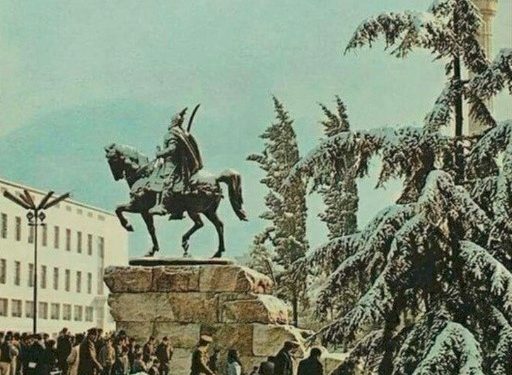

All Albanian museums resemble one another. They start from the principle that the present population must be educated right on the spot-that the schoolchild, the citizen, or the peasant from the Shkodra or Gjirokastra region must find a museum located there to contribute to his education. The central government has thus gifted every provincial chief town with a standard kit: prehistoric axes, Greek, Roman, Byzantine coins, documents of the Ottoman occupation, of the Albanian people’s resistance against Turkish oppression. Where original documents are missing, copies have been placed. This latter period, mentioned above, was dominated by the deeds of the national hero Skanderbeg, about whom we will speak during a visit to Kruja.

The road to Kruja was not good at all to reach the height of the castle at 605 meters, but our cars climbed it comfortably, after a small stop where we admired many lime kilns. A large, very dusty artery ran along the very large swamp that is being drained and precedes Durrës. We did not take that road and followed an alluring advertising billboard where a modern Albanian beauty revealed some of her beauty; thus, we followed the road along the most modern beaches of Albania.

Isolated from the road by large poplar plantations was, right by the beach, a whole town of villas and hotels, rest houses, the most valuable part of which was the large “Adriatik” Hotel, where our stay was planned. We asked for the elevator but found that these bourgeois mechanisms did not exist. We had to carry everything up with our hands.

By a refined selection, we were on the top floor from where, it must be said, the view was excellent over the very large red-sand beach. As soon as we went to our apartments, a luxury room with a toilet, shower, and vanity, I observed the deficiencies of this apparent luxury. The hotel, built during the old regime, had undoubtedly not seen any spare parts stored for its benefit. Coming in one after another, the children who had an apartment just like ours began to complain to us. The toilets incessantly played the lamenting song of the tank that was constantly leaking water: as for the showers, they had now turned into real puddles, in which one could splash up to the ankle.

But all these were minor things… what would cause us the greatest disappointment was the complete lack of any idea regarding the service that must be provided to clients in the hotel, which outwardly was equal to the most beautiful Western hotels.

At dinner, after we had to wait as long as in the Soviet Union-which is not an exaggeration-a workforce dressed according to the norms, but possessing none of the true qualities of modern hospitality, dumped onto our table a lukewarm and insufficient meal, which made us remember with regret the fine linen service and the generous cuisine of Shkodra. / Memorie.al

Translated by: Nestor Nepravishta