Memorie.al / We all have our little stories that our mothers told us about the day we were born, but Çiljeta Bome can fearlessly call her birthday the most ominous day for her mother, Qerime Bome. It was 1972, in communist Albania. Exactly on the day she should have been rejoicing over the birth of her daughter, Qerime was violently taken from her hospital bed by the State Security (Sigurimi i Shtetit) and sent to a cell, without being given the chance to breastfeed her infant. Even though she had just given birth, the communist regime did not spare her; they tortured her in the most inhumane way and sentenced her without having committed any crime.

Çiljeta did not feel her mother’s love in the first years of her life, but she felt her pain to the bone. She wants to share this story with others, as a reminder of the suffering of her mother and other mothers and daughters under that savage regime.

We are publishing her testimony in full in this article, referring to the stories of her mother, Qerime:

The Testimony of Çiljeta Bome

“My mother’s story is one of the most tragic of the dictatorial regime of Enver Hoxha. All the persecuted deserve respect for their suffering, but my mother’s story is beyond painful.

My mother, Qerime Bome, comes from an honored, patriotic Kolonjar family! Qerime’s father (Ramadan Bome) was a Kolonjar merchant, a patriot, a nationalist, but after 1944, the communist regime tried him in absentia and sentenced him to death, accusing him of being an enemy and a traitor.

My grandfather went to America and was always active in ‘Vatra’ there, because he was a loyal friend and comrade of Mid’hat Frashëri.

My grandmother, Selvi Bome, who raised me, told me these things. That’s where the ordeal of suffering for the Bome family began. My grandmother and the seven daughters who remained were interned, and all their property was confiscated.

The family served their internment sentence in a barbed wire-enclosed camp between 1945 and 1950. When the internment ended, with the help of some well-known Kolonjars, the family settled in a neighborhood in Tirana, living there in rented accommodation.

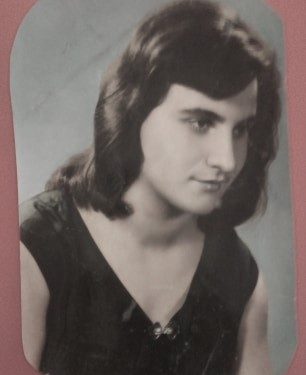

The daughters got married, and my mother, being the youngest, stayed with my grandmother. My mother met my father, who had come from Gostivar and was a music student. My mother had graduated in painting, and art brought the two together. This is where the struggle became even fiercer. My mother married my father, Daut Mustafai, but without an official certificate, because my father was a foreign national.

After the marriage, they were given an apartment in Lushnjë because an artistic enterprise was opened there, and my mother was appointed to be the head of production, to teach the workers. In 1972, it was time for me to be born. My mother was nine months pregnant and had come to my grandmother in Tirana to give birth.

As she was waiting for my father to pick her up and take her to the maternity ward, she learned that the Sigurimi had arrested him a few days earlier on the train while coming to Tirana. They had arrested Daut, as well as other family members: the nephew Robert Burimi, the Aunt Afërdita Hajrullai (Bome), some cousins and relatives, whom I do not want to, hurt by mentioning them.

Finally, when Qerime (my mother) presented her at the maternity hospital to give birth, the State Security arrived and told her: “We have a question for you,” and they took my mother to the investigation cell. There, her labor pains began, seemingly from the pressure and fear, and after many hours of crisis, they decided to take her to the maternity ward to give birth. But the Sigurimi waited for her outside the hospital doors.

After a difficult birth, they took my mother, with blood still on her legs and her breasts swollen with milk, and put her back in a cell, in the investigation unit. As she told me, it was just a dark cell, 1 square meter, with only a very small window high up.

There in the cell, the doctor would come and bandage my mother’s chest to stop the milk from her breast. My mother told me that the walls of the cell were smeared with her milk…! An unimaginable horror for a woman who had just given birth.

The interrogator Dolorez Velaj and the interrogator Elham Gjika would come there and accuse her: “You are an enemy, you wanted to overthrow the people’s power, and we have facts about this.”

This Dolorez pulled my mother’s hair through the cell, uttering offensive words. Elham, the interrogator, provoked her by saying: “We have your husband here, your nephew, your sister, and they confirm that you are the cause of their imprisonment.”

What things they didn’t accuse her of in the investigation unit. During the confrontation with Daut (my father), who was covered in blood, he whispered in my mother’s ear: “Forgive me, Qerime, if I said something, my soul knows, as you see me, what I have endured.” They brought in the nephew, Robert, who was a child of about 18 at the time, barely standing, and then they brought in the sister, Afërdita.

My mother was psychologically devastated when she saw her loved ones and shouted: “Release Afërdita because she has diabetes, transfers her sentence to me.” There, Qerime gathered herself and said: “You are criminals, I have not been involved in politics until now, but now I am convinced that you are animals, murderers, and criminals. Down with all of you, and I will sign the indictment, because I hate you until death.”

They gave her a pencil and paper to sign, and she broke the tip of the pencil forcefully (they understood the message of breaking the pencil). They asked her what she would name her newborn baby, and she said: “You closed my life at a young age, so I will name my child; Çil Jetë – Çiljeta (meaning ‘open life’).”

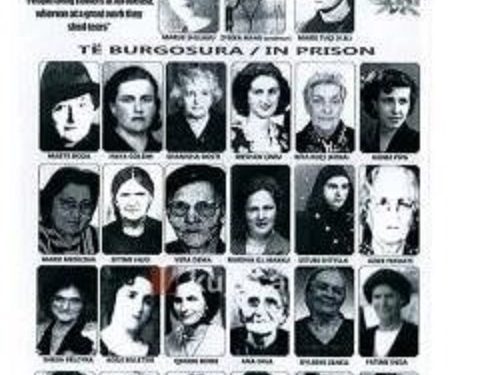

Qerime was sentenced to 15 years, accused as the leader of the hostile group, in a military court. My aunt, nephew, and father served 5 years of political imprisonment each. I stayed in the maternity ward for about two months, and my grandmother came, signed, and took me.

A doctor there warned my grandmother: “Come and take the baby, because a plan has been made to make her disappear, and you will never find her again.”

Qerime was initially sent to the “Qyteti Stalin” prison, then to Kosovë in Lushnjë, in Unit 318. My aunt, Afërdita, was also there. My father, Daut, was in Burrel prison, and the nephew was there too.

My mother was released in 1983, by special decree, as the amnesty did not cover her, because my grandmother and I left no stone unturned with letters. My grandmother, who raised me, and I remained at the gates of the prisons, in Kosovë, Elbasan, and Burrel. Qerime had excellent behavior in prison, socializing with the convicted Russian women, as she told me: “You had something to learn from them.” My mother was very close friends (like a sister) with Nadezhda Sidorova in prison.

My mother died in 1992, from a serious illness; these were the consequences of the prison. My father also died a few years later, in 1997. Both very young. I grew up as best I could, sometimes with bread and sometimes without, because my grandmother did not have a pension.

We were terrified; we were always monitored by the representatives of the Front and the Internal Affairs Branch. They always called me “reactionary”; this word is ingrained in my mind. We, the children of the persecuted, demand moral justice, so that the souls of those who left this life with such pain may find peace, and rest in peace.

It is our duty to show the younger generations what the dictatorial terror did, what the terrorist Bolshevik dictatorship did to the Albanian intelligentsia.” Memorie.al