By Odile Daniel

Part Two

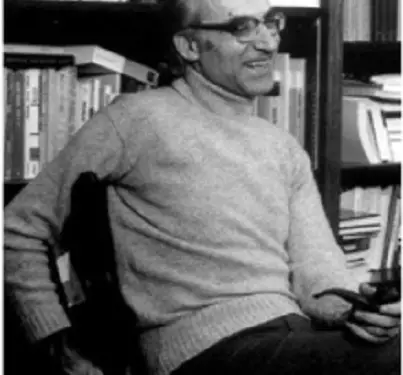

Memorie.al / I was in Paris when, in May 1992, I received a phone call from an Albanian from Washington, who wanted to meet me. He was a retired professor of Albanian and Italian language and literature, named Arshi Pipa. He had read some of my works on Albania and we had begun to collaborate by correspondence, especially with the creation of a magazine entitled ‘Albanica’ that he had published in the USA. I arranged to meet him in a café near the Saint-Sulpice church, because he was staying in a hotel in the Quartier Latin. I knew the value of this professor from his great name, because in 1978 he had published in English in the collection ‘Albanisce Forschungen’ (Albanian Researches) of the University of Munich, three volumes on Albanian literature. He had also published, always in English, four other volumes in the USA, in the collection ‘East European monographs’ published by Columbia University Press in New York; the first volume, published in 1984, compiled by a group of authors under his direction, was about Kosovo. The second, published in 1989, was entitled ‘The Politics of Language in Socialist Albania’. The third, ‘Albanian Stalinism, Ideo-Political Aspects’, published in 1990, was followed in 1991 by ‘Contemporary Albanian Literature’. I did not know the intellectual journey of this Albanian, but I was amazed by the knowledge and the finesse of his analyses. He had taken over the direction of the magazine “Dielli”, of the Albanian community in the USA.

Continued from the previous issue

We met again with Professor Arshi Pipa, on the occasion of a conference he gave at a research institute and, during a dinner at the end of the meeting, where he somewhat relaxed when I asked him about his family, because I had felt that he spoke easily about this topic. He felt very bitter about the misfortunes she had suffered because of him, more than about his own suffering.

– “The communists, he told me, expelled my family from the capital. They forced me to move three times, within six months, that family where my parents and three sisters, Nedret, Fehime and Bukurush, as well as the two orphans of my sister Bedi, who had died of tuberculosis, lived together. When I was finally able to speak to one of my sisters, after almost fifty years of silence, she told me that a neighbor, a young man who lived in one of the small apartments where my family had lived in Durrës and who had been my student, had been sent by the Party to visit me in prison, to see if I had “softened up”. I replied that I had done nothing wrong; therefore, I had no reason to repent.

When I was imprisoned in Durrës, my family did not tell me that my brother had died under torture and, on the few occasions when they came to visit me, they did not put on mourning clothes. However, I learned the news from another source. I also lost one of my other sisters, then my father became ill. He had broken his hip. He became an invalid. He died, struck down by a heart attack, during a transfer in a cart. My mother did not even manage to get an ambulance to transport him. In a short time I lost three members of my family.”

– What terrible suffering!

– “I saw many people suffering around me; intellectuals, engineers, clergymen, but also peasants and workers. The trials were just vile farces, because the decisions had been made long ago by the Minister of the Interior. Vincenc Prendushi, a Franciscan, a great poet, who was the head of the Catholic Church, was arrested at the age of 86 and accused of being part of the “reactionary clergy”, of being an “enemy of the people”, a “collaborator”, a “fascist”, an “agent of the Vatican” and of having attempted to overthrow the government. He was sentenced to twenty years in prison and forced labor. He answered the court that he had never done anything wrong in his life, that he had not practiced any discrimination.

I remember it well, because I shared the same small cell with him, along with about thirty other men. We were crammed into less than 40 square meters, but we left space around the Archbishop as a sign of respect for him. Moreover, there were no longer any differences between us prisoners: our social position or our intellectual education mattered little. I sat next to him and we became friends regardless of religious affiliation, because I am a Muslim. We remained together until the day of his death, in 1948. Our conversation was mainly about literature and, especially, poetry.

I added:

– Monsignor Prendushi participated in the collection of the treasures of Albanian oral poetry. He also wrote very beautiful poems such as ‘Leaves and Flowers’ and translated masterpieces of European literature into Albanian. The Archbishop of Shkodra also acted as a mediator in the very difficult times that Albania was experiencing at the beginning of the period of independence in 1912. How is it possible that he was treated as an enemy of the people?

– I suffered a lot for him, Arshi Pipa told me, when he told me that they had tortured him. The police had beaten the old man with sticks. They had tied his hands and feet and hung him from the ceiling of a room where he had suffered until he had lost consciousness. Monsignor Prendushi was subjected to forced labor. He had to unload logs of wood from a cart that was at the foot of the hill on which the prison was located and bring them to the buildings. It was hard work for him, who suffered from a hernia. The guards never stopped mocking him, insulting him with their tone of voice, when they only uttered the word “Priest”! They mocked him, saying: “Have you never worked in your life”?! And they took advantage of this to beat him and load large logs on his back.

– Did he die from torture? I said.

– He died in the Durrës hospital where I was hospitalized at the same time as him. He suffered from a heart condition and an asthma attack. The doctors were very dedicated to easing his pain. I thought that at the time of the breakup with Yugoslavia, he might benefit from some amnesty, but that was not the case. I often stood at his head at night and listened with great pain to his groans, due to his asthma. I tried to massage his feet, as we often did with sick prisoners. The problem was that it was very cold. We didn’t have enough wood to keep the fire burning all night. And we were in the dark all the time. The bishop reminded me of Goethe’s words: “Light, more light”! He repeated the words of the Albanian proverb “Let your eyes be light, for the world”! It was a call for enlightened thinking, but also for spirituality and mysticism. Vinçenc Prendushi had the same fate as many other Albanians, accepting to die without betraying their beliefs. He died in February 1949. I closed his eyes. He found peace. He died for his ideal.

– When do you plan to return to Albania to meet with your relatives, with whom you have been separated for so long and have not even been able to correspond?

– I will return to Albania in a few months, when the democratic process has started well; I will go after over thirty years of absence. What happiness to see my homeland and my family, after such a long absence, like an eternal night of silence!

Arshi Pipa never stopped fighting with his feathers so that the culture of his country would not disappear. Through the discussions we had, it seemed that he had no intention of getting politically involved, but as a sincere democrat, he wanted to support the Albanians’ progress towards democracy. He had a very liberal spirit.

Professor Arshi Pipa greatly appreciated that his voice could be heard at conferences in Europe, at a time when the media was interested in the upheavals in the former Eastern countries. In his public interventions, he did not present himself as a victim, remaining reserved, regarding his personal journey. He spoke more as a man of letters and a philosopher and analyzed political developments, in a broader context. In private conversations, he had a sense of humor like all the inhabitants of Shkodra. He talked to me a lot about literature, especially Italian literature, with which he was much attached. He liked to tell anecdotes, taken from the stories of Boccaccio’s Decameron, which had fed his imagination in prison. One day, he spoke to me laughingly about the period he had lived in Albania, after his release from prison:

– After my resignation, my family fell into poverty. My sister and I lived by selling buttons, which we produced ourselves with clay that we heated and dried. Then we cut circles, where we made holes to pass the thread and painted these buttons in different colors. My sister, who was forced to work in a brick factory, was very good at this. What did we not have to do, for a bowl of soup!

– What a beautiful job for an intellectual! I said, while you could have used your knowledge to educate the youth. Albania was deprived of its best intellectuals by exterminating them, imprisoning them or scattering them in the villages to work the land. What a waste! Apart from a few people of integrity, the pseudo-scientists and pseudo-scholars, who made up the new intellectual elite, did not stop singing the refrain of the Party’s songs and boasting of the thinkers Marx, Engels, Lenin and Hoxha. I remember a literature professor, a supporter of socialist realism, whose writings criticized classical literature, who looked at me with wild eyes when I crossed paths with him in the corridors of the National Library.

– It must have been Koço Bihiku. I too suffered his hostility. He was my student in Durrës. He participated in my punishment.

– Yes, that is precisely what I am talking about. Arshi Pipa had always remained reserved, as far as his persecutors were concerned. When I met the professor another time, I was curious to learn his opinion, regarding what the Albanians called the “unified language”, the official language of Albania, carefully elaborated at the beginning of the communist system; so I asked him about this issue:

– During the government of Enver Hoxha, I often noticed an impoverishment of the Albanian language, reading the press and propaganda documents as well as university publications. In them unfolds a rigid, uniform language, impoverished by the richness of its vocabulary. It was as if filtered, tempered with restraint, tamed, puritanical, kept under the control of the Security. Through linguistic expression, you could easily distinguish quality scholars who demonstrated an innovative pen and who unfolded a language outside the framework.

– Yes, I have noticed, but I want to remember one of my battles, the one against the establishment of what is called the unified language, Arshi Pipa answered me. We must talk about the shame of the reform that began in 1972, to create a new literary language.

I interrupted the professor:

– I know that Albanian is a language with two dialects, consisting of Tosk in the South, spoken in the Myzeqe area and between Berat and Korça, with several regional variants, and Gheg, spoken in the North, up to Elbasan, also with its regional variants, as well as in Kosovo and Macedonia. In addition to other differences, Tosk uses the voiceless ë and the obstacle in the use of r, Gheg is distinguished by the use of nasals. You have written many works in English, but your first books and memoirs were written in the Gheg dialect. Now, the Albanian that is taught and all the writings that I have read, covering the period after the fifties, are written in the Tosk dialect.

– The linguistic forms that you find are those that belong to what I call ULLA, an abbreviation of the English terms Unified Literary Language of Albania. The language policy of the communist government was to smooth out differences and create a common way of expression.

I felt like laughing when I heard the term ULLA, because, in those years, erotic advertisements were often seen on walls on which the name ULLA was written in large letters, next to a Nordic-type woman’s face, accompanied by a pink Minitel phone number. But I remained serious and continued listening to the professor.

– Before the war, in 1917, a literary commission was created in Shkodër. He thought about the convergence of the two dialects by choosing the Gheg dialect of Central Albania, that of the Elbasan province, with the aim of arriving at a common literary language. This choice was proposed by the great linguist Gustav Weigand, who had published in Leipzig, in 1913, a grammar of Albanian in the southern Gheg dialect. He took into account the dialects of the provinces of Durrës, Tirana and Elbasan. After 1950, the ideological line of the Albanian Communist Party prevailed. It was inspired by writing by Stalin, ‘Marxism and Linguistics’ published in 1950, which states that; when two languages are in conflict, one of them wins and the other dies.

He was referring to the theory of N. Marr, a Georgian linguist, who supported the idea that the vocabulary of one language should dominate the other. In fact, there was no conflict between the two dialects of Albanian. My mother was a Gheg and my father was a Tosk. We never had any disagreements in speech or writing. With the establishment of communism, it was quickly forbidden to speak Gheg in schools, offices and on the radio. Within ten years, a centuries-old coexistence of the two dialects came to an end. Gheg disappeared from school books. The government demanded a quick reform. However, a great Albanian linguist, Eqrem Çabej, said that; studies had not progressed sufficiently and that a continuous approximation was needed over time. This linguist also suffered; he was isolated for “foreign views”. In 1954, the Albanian dictionary, directed by Androkli Kostallari, director of the Institute of Linguistics in Tirana, sealed the hegemony of Tosk.

It should not be forgotten that most of the communist leaders were Tosk. A real Gegophobia was created, while Gego showed a great phonetic richness, illustrated by our oldest authors. For the communist government, this issue of embracing a common literary language had to be resolved as soon as possible. Since the first Albanian authors and the greatest writers of the 16th and 17th centuries were products of Gego and, at the same time, of Catholic priests, the Party recommended the rejection of the Gego dialect.

– You mention Androkli Kostallari. I remember what he said when he came to give a speech at the Institute of Oriental Languages in the framework of cultural exchanges with France. He presented Albanian linguistic science as if it had all been created since 1945, from nothing. He declared that before the Liberation, nothing had been done: neither dictionaries nor grammars. His claims were even ridiculous. With his mouth he expressed the opinion of the Albanian Communist Party, which had taken over all Albanian scientific production and which implemented a violent nationalism. Could he be excused, thinking that in the hall, there must have been some collaborators from his country, tasked with supervising his speech? However, his writings reinforced what he said. How could this linguist bring the broom to the authors of grammars and dictionaries, such as Frang Bardhi who had published a Latin-Epirot dictionary in 1635, Gasper Jakova, author of a grammar, Peter Mazreku from Prizren, author of a dictionary, without forgetting the Albanian-Greek dictionary of Kostandin Kristoforidhi in the 19th century and the dictionaries of Nikollë Gazulli, killed in 1946?!

– In my opinion, answered Arshi Pipa, the authorities wanted to reject the influence of the Latin world, that of the West. They also wanted, and especially, to eliminate the intellectual elite of the North, which had not been continuously active over the centuries and which threatened to create an opposition movement, in the minds of the people. For this purpose, all the Party documents, from the beginning, were drafted in Tosk. The press, radio, theater, cinema, all sectors of cultural life, had to be convinced. In ten years, the centuries-old coexistence of dialects came to an end. Gheg was banned, but linguists, tasked with inventing ULLA, were forced to take specific Gheg words that were not found in Tosk and Toskize them.

Deep down I thought: “it’s exactly ULLA, a kind of prostitution of Gheg”, but I let Arshi Pipa speak:

– The Albanian language has been stigmatized by that totalitarian state, which was Albania during the period of Stalinist rule. The government wanted to shape a homogeneous state, under the banner of communism. It implemented the slogan; “one nation, one language”, imposing on the entire territory the “unified language”, which was not the result of a gradual approximation, the natural convergence of the two dialects of Albanian; with quick and sudden decisions, it sanctioned the choice of Tosk, the southern dialect, to the detriment of the peculiarities of Gheg, the northern dialect. In this way, the hegemony of the South over the North could be realized. The Albanian case clearly illustrates how an arbitrary political power can manipulate the linguistic weapon to impose itself on the entire territory. From now on, the unified language could propagate ideology.

– I think that these sudden changes must have been badly received in the North!

– Yes, but the Gheg language was preserved in the family. Know that the grammars published abroad, that of Namik Resuli, published in 1985, in Padua, that of Oda Buchholz and that of Wilfried Fiedler, in Leipzig in 1987, as well as that of Martin Camaj, published in Wiesbaden in 1984, respect the constituent elements and the development of the Albanian language. What will happen in the current movement is a renaissance of the Gheg language, especially in conversations between the people of Gheg; there will be debates, but the unified literary language will survive. It is too late for a change.

Thinking about the discourse that Professor Pipa had supported in several publications, I asked him the question:

– What did they think of you in Albania, because all your demonstrations, all the truths that you defended in your writings, even though they could not be read in the country, must have reached the ears of the Albanian leaders and communist elites?

He replied:

– I was aware of everything that was written about me, of all the humiliating words that were said about me. This did not scare me and did not make me change my mind.

– But was your honor touched?!

– Yes, but I have no hatred. This was a typical communist attitude. I do not know if my critics really meant what they said or wrote?! They criticized me so that they would be seen favorably by the regime. They were encouraged to do this, in the climate of fear that reigned, to show that they were not opponents and that they did not approve of the ideas of the Albanian intellectuals in exile. They were afraid of prison.

I mentioned the opinions that had been issued against the professor:

– I have found many times the usual formulas of speeches to fight opponents, not only in the writings of Enver Hoxha, who had written dozens of works, but also in those of Albanian writers and scholars, both in Albania and in France. Albanian oppositionists were treated as CIA agents, agents like the UDB (Yugoslav secret services), as revisionists and social-imperialists, etc.

Arshi Pipa, without batting an eyelash and without resentment, answered me calmly:

– Yes, they called me a CIA agent. The criticisms against me went as far as paranoia.

– In fact, in his work ‘The Titists’, Enver Hoxha made this accusation against you, a completely classic accusation!

– He even wrote that I had fled my country, in the hope of gaining fame in the West and that I was a mediocre writer, without glory and jealous of Albanian writers of socialist realism. I was accused of being a denouncer. He even criticized me for being old and sick.

– Meanwhile, the ten years of prison you have spent should inspire respect. At the same time as the criticisms that aimed to make you considered a spy, as one of the most fearsome enemies of the regime, false news was circulating against you, such as those that said that you had escaped to the USSR and had written a biography of Enver Hoxha. That didn’t make sense?!

I thought that the time had come to defend the honor of Professor Pipa, one of the many victims of Albanian communism, and for the truth to come out.

Professor Arshi Pipa was not vindictive and did not want to enter into controversy. His concern had been the fight against a destructive ideology. He had no personal hatred against his critics.

Arshi Pipa died on July 20, 1997, in the USA. The courage and intellectual values of this humanist were rewarded. He was declared an ‘Honorary Citizen’ of Shkodra. Currently, his memory is immortalized and honored by the “Camaj-Pipa” Publishing House, which bears his name, along with that of another Albanian, writer of emigration: Martin Camaj. There is also a literary prize “Arshi Pipa”.

As a loyal patriot, Professor Pipa, preserved and protected the cultural memory of his country. Albania finally gave the place he deserved to this great scholar, who had been slandered, and erected a bust of him, just like his brother, that great martyred patriot. Memorie.al