From Shpendi Topollaj

Memorie.al / When the couple Elisabeth and Jean – Paul Champseix (Shanse) came to Albania in the 80s as teachers of French language and literature, of course they had read Pierre Gilliard’s book which, many decades ago, had went to Russia, with the same task, where he had known closely the hateful paradoxical communist experience of Lenin’s power. They, however, were spiritually prepared for the sad reality they would find here. But they would never have believed that this reality would be even more bitter than that of Byzantium, for which W. E. H. Lecky, in 1869, in his book “History of European Morals”, notes that: “The history of empire is a monotonous narrative of intrigues… poisonings, plots full of ingratitude and endless murders”. No or no! Louis XIV, the ‘Sun King’ who really ruled for 54 years under the authoritative slogan “The state is me!” had fallen on the neck without right. and on the statue of Jupiter in the garden of Versailles he put his face, but his time, for better or for worse, entered history as the “Golden Age.”

But the Albania of the dictator Enver Hoxha, who spread barbed wire everywhere, turning the whole country into a prison, expropriated them, shot them, impoverished them and terrorized them until they turned their ragged citizens into slaves, silenced them, limited their thinking and made them hypocrites in the name of the creation of the new man, the biggest lie that was ever articulated, could it be called anything but the “Time of Misery”?

We were also lied to, because we had the opportunity to get to know each other and compare. But not those two good and wise Frenchmen, who came from the heart of the democratic, prosperous, civilized and cultured west. Foreigners have always visited Albania and most have expressed their impressions in writing.

For our conditions, we remain forever grateful to them, because in the end they illuminated the path from which our history passed. We are not angry with them even when they have truthfully painted the real picture of poverty.

After all, they have never hesitated to highlight our values and virtues, with which we have always felt proud in front of everyone. They were particularly impressed by the generosity and hospitality of the Albanians who have kept the door open day and night for their friend. As if they have ascertained the sincerity, openness and extraordinary respect for them. And for that we felt good and not at all ashamed.

But as you read the book of these teachers, because a void is created inside you and scenes from the great absurdity of that time reappear, which not only make you blush, but also ask for your responsibilities that allowed us to bend to the limits of the unbelievable and as naive we believed in the lies of ignorant communist criminals.

This gullibility was well explained by Stalin’s translator, Valentin Berezhkov, who, in his memoirs, concludes that: “I was one and a half years old when the Tsarist Empire collapsed. My grandson is turning so when the Soviet empire collapsed.

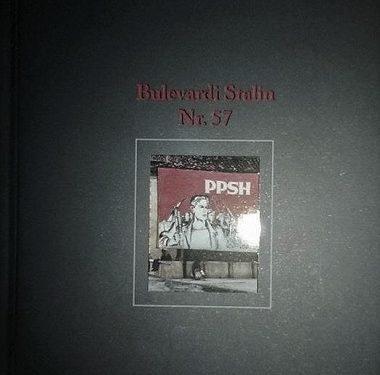

May God not let him experience what my generation had to go through…!” That here in our country, not only the street where they lived bore the name of that hated man, not only his statue dominated and defied the minds of the citizens, but also the ideology that he experimented with his people, prevailed and was implemented without the slightest murder of conscience, for the damage it caused.

It is easy to understand that the authors loved our country, the Albanian people and felt themselves missionaries of progress. But they have not been able to close their eyes to the germinal gloom, to the hypocrisy of the people with whom they were connected by work or whom they happened to meet wherever they went.

How could they not be impressed by the permanent and often ridiculous surveillance by the State Security? How could they not be bothered by the vigilance of the political leader of the faculty where they taught and that of the vigilant virgins, as they called the youth secretaries.

Everywhere, those friendly people, eager for conversations, discussions and debates, were surrounded only by doubts, so much so that they declare: “We could not remove the distrust of others, and after a while, one feels humiliated in search of contacts with others. We had no choice: either to ignore this place or to discover it with our own means without changing ourselves”. And they chose and best realized this second path that paradoxically also avoided the first one; disregard.

Confined as they were, without contact with others, as no one came in and no one ever invited them into the house, understandably out of fear, they, with a strange sense and rare insight, managed to see everything and analyze every today’s phenomenon and event, retrospective or prospective.

Walls and streets filled with banners, everywhere fields planted with bunkers, occasional pompous speeches and “success” parades, newspapers, radio and televisions filled with propaganda talking about the depletion of bourgeois and revisionist countries and the happiness of Albanians, war freedom of conscience and belief, turning cult objects into military wards and vegetable warehouses, a miserable architecture, endless queues for something to keep the soul alive, ever-increasing shortages, no roads and no modern traffic, restrictions from the most the unbelievable, even to films and literature, where foreign authors were chosen with the precision of pontifical fikes.

Plenums with declarations of enemies that never ended and ended with severed heads as in the days of Robespierre’s France, the killing of young men for attempting to cross borders, and long years of imprisonment for a word of mouth – these are the aspects that were painted in the eyes their place where they were assigned to work for six years in a row.

When they passed on the street, how could they not notice the general surprise and envy of the passers-by for the shoes these strangers were wearing, or the distressed look of the children looking for a pen or chewing gum. It is understandable that in this mosaic of caricatures, you will choose both irony and sarcasm as a means of description, so you often cannot stop laughing while reading. Although it is for crying.

Remember the case of the employee of the Italian embassy who, together with children and soldiers, asked him to account for what he wanted in that thicket, where the black man had defecated out of trouble and the son of Ulconja had to justify himself with the language of Dante that he had not done some kind of espionage or that of the security guards who at night, while guarding the palace where foreigners lived, covered their heads and rummaged through the capitalist garbage bins for some rags. All these and many others, the French couple recognized immediately, while the communist leaders stubbornly continued to pretend they did not see them.

There are notes of regret and sorrow when they show how the soldiers kill their compatriot Jean-Marie Maselen, organizer of the Club Mediterranee of Corfu, while fishing. “Only a few kilometers separate the place where the club is located, whose motto is satisfaction, and psycho-rigid Albania, which is waiting for any attack with a rifle in the eye?

It’s only natural that the meeting between these two worlds creates sparks.” In the book, I find impressions about the gypsies, the minorities in the south, the Kosovars and the national problem, the Popa brothers who marked the first crack in the Albanian “Titanic”, but mostly there the relationships and mentalities of the students take place, as the professors are directly connected to them by their work.

They are eager for knowledge, cultured, curious, but not yet prepared to face the truth and think independently. Even when they speak, they are guarded and want to communicate without others around. The questions they ask are interesting and show their displeasure. “Students – claim the authors – want to be considered Europeans. They suffer when they find out that their country for many foreigners is a big question mark on the map”.

But they know entirely European intellectuals such as: Vedat Kokona, Misto Treska, Jusuf Vrioni, Tedi Papavrami and even Ismail Kadareja, whose work analysis in this book very rightly occupies an important place, as it is as it says our famous writer, Visar Zhiti:

“Always in my opinion, the “Kadare phenomenon” happened in Albania, unique in the literature of other countries, strange, beautiful and sustainable. Kadare’s literature really coexisted with the dictatorship for a long time, both at the peak of their powers, but it did not become its own nor was it defeated by it. It became a different value, a surplus value, for all Albanians, true spiritual food, and managed to break the isolation, becoming part of the world culture, the best, from the best”.

Wonderful connoisseurs of literature, the authors see Kadare’s work and his anti-communism with cold-bloodedness and impartiality, not to mention with admiration for the genius talent and absolute inclination towards the West. They write with pleasure: “The paradox is great: in closed anti-Western and very nationalist Albania, it is his success abroad, more precisely in France that would make Kadare the leading national writer of the time.”

And the long essay on Kadarena closes with the analogy he implicitly makes with Aeschylus, who: “… deep down he felt that he had the whole of Greece on his shoulders and, no matter how much he foamed, no matter how much he moved his shoulders with fury ; he could never shake it. They were said to carry each other through the millennia. He Greece and Greece that. He felt that this was a fatal connection, but in that fatality there was also mourning, and light, and sorrow, and happiness, and loss, and resurrection…”!

Except for the fact that he had not been born some 25 centuries earlier in Eleusis and had not participated in the battles of Marathon and Salamis, does not the great tragedy and lyricism of Aeschylus match the colossal work of Kadares itself? Does he not have the indisputable role of making people aware of the necessity of great change? Of that change where the copying of Stalinist Russian tsarism led us, which, according to Berezhkov, came and went with a black face, just like here with us:

“The poverty, the despair, the endless lines for the most necessary things, the loss of faith in the “bright future”, the emptiness, the complete lack of hope, as well as the fear, which filled the souls of the people, all these burst out at the edges most different of the former B.R.S.S. – through the frightening face of violence and at any moment they risk returning to a general fratricidal civil war”.

The only haste of the authors, in my opinion, is the designation of the deceased: Dritëro Agolli, whose talent is not denied, like ‘Cerber’ and Alfred Uçit, as an inquisitor of aesthetics! They remain two of our outstanding intellectuals who have never hesitated in their sincere wish that: Ismail Kadareja deserves the Nobel Prize. And the fact that a long time ago, the then President of France himself, awarded our Kadare the highest award is of great significance.

We are all grateful to France, just as we should be grateful and officially appreciate the work full of dedication and foresight of the French couple. Elisabeth and Jean-Paul Champseix for what they did during their stay in that narrow apartment on “Stalin Boulevard”, in the Albania of that time, and for this book with shocking truths that should never be forgotten.

That today that things have changed for the better, we too, without fear that they will misunderstand us like they used to, that secretary of the party, we can say to them with our mouths full: “Now you have taken the shadow of the Albanian!” Memorie.al