By Reshat Kripa

-The unknown story of the journalist and writer Halil Laze, and a look at his book “The Impossible Escape”-

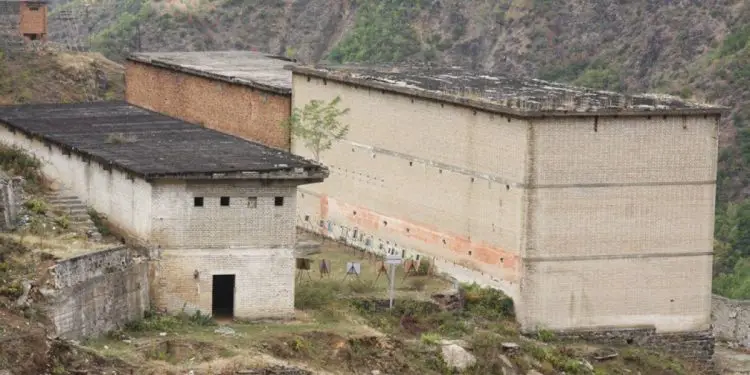

Memorie.al / As early as the first page of the book ‘Impossible escape’, by the author Halil Laze, we come across the call of a political prisoner, in the Spaçi camp, or in “the place where the devils hatched birds”, as the locals called it : “O God, will there be a man who will write these sufferings of ours”? And this man who would write about those sufferings, would be him, the son of the martyr of the National Liberation War, but also the grandson of the two fallen, from the ranks of the ‘National Front’, the well-known journalist of a military newspaper who, suddenly and without remembering, like many of his friends, he had turned into an “enemy of popular power” and, as a consequence, was serving his sentence in the same camp, where the prisoner of Spaçi camp, which I quoted above, had also suffered. This man was a young man, not yet thirty years old, newly married and with a son who was not yet two years old. This man was Halil Laze.

I flip through the pages of the book and strangely I find myself imprisoned again, as if I am working as a slave in the terrible forced labor camps. The camps of Maliqi, Beden, Ura Vajgurore, Vlashuk, Shtyllasi, Bulqiza, Rinas, Thumana, Zadrima and many others from my period come to mind.

Surprisingly, the horrors of those camps seemed to me to be the same as that of Spaçi, skillfully described by the author. And it could not be otherwise. The dictatorial regime, which had devoured the country, could not act otherwise!

The Macbeths of the twentieth century were drowned in blood and every day sank deeper into those puddles they created themselves. In front of my eyes is the man from Shkodran who, after receiving the news that his wife had left him, went towards the barbed wire to end his life.

The bloodsuckers could capture him and bring him back to camp. But no, they wanted blood, so they started shooting at him, from all sides. And when he was seriously injured there, they left him without help between the wires, until he breathed his last.

He was an immigrant returned from France. This had cost him prison. They had accused him of being a French agent. Sentenced to fifteen years in prison. No one mentioned his name. Everyone called him “the Frenchman”. No relative came. Only the camp mates helped him from time to time. Finally, he couldn’t take it anymore. He jumped over the fences of the camp, where he died, under the barrage of bloodthirsty bullets.

Aristotle, a minor, had been arrested before finishing high school, together with his friend, Kosta. Now he was seriously ill. The cancer was crushing him. A strong pain tormented him. At those moments, he would go outside and call out to the sky: – “Oooooo Zoooot! Ooood!

Costa caught him and both of them, crying, entered the infirmary. But the command did not believe it. They called it simulant. Once, they punished him by putting him in a dungeon. As he prayed to die, to be saved from suffering.

Reading the book, many distinguished and honorable figures appear before the eyes, which never broke before the monstrous machine, which constantly hunted spies and provocateurs. In the multitude of these, let me mention Cezar Toro, who was imprisoned almost as a family, together with Ylvi and Qazim.

The mechanical engineer (Laureate of the Republic Prize) Ismail Farka, who, during his studies, had fallen in love with a Russian woman of Jewish origin, which would be the reason for his imprisonment, regardless of the fact that he was the nephew of Ije Farka, in the house of which was also hosted by the head dictator Enver Hoxha.

Xelal Koprencka, the known ballisticsman who had been convicted three times until then and two more punishments were waiting for him, the latter capital, after he had dared to write a letter to Ramiz Ali and Hysni Kapo. Vangjel Lezhon and Fadil Kokomanin, the two confirmed journalists, who were shot together with Xelal, for the same reason.

Cry Sadik, who couldn’t bear his informant to appear in front of his eyes, or Xhafer Agaraj, who didn’t spend more than ten days as a brigadier, because he didn’t know what submission was. Jamarbër Markon, the son of the well-known poet, Petro Marko and the famous painter, Ali Osekun.

Bardhosh Gjonzenelin from Vlora, the son of the commercial school professor, shot in 1951, and Thoma Grillo, who had dared to hit the dictator’s portrait with his shoe. Seit Bathoren, Baba Myslymi’s former friend and Chairman of the People’s Council.

He asked Baba that; who was to blame that Beqir Balluku was in prison and told him in good faith that there was a deposit full of weapons at home. But he had not yet gone there, when he was arrested and condemned, to return suddenly to; “enemy of the people and popular power”.

The main motive of the book, as emphasized in the title, is the constant desire of the prisoners, to break the shackles of captivity, to fly free. The details of this escape are given in the book through the dialogue of the characters of the work. Some are for, others against. Some are for mass escapes, others for special ones.

Above all, the figure of Ahmet Hoxha, who had served twenty years in prison and had many more to do, stand out. It was the prototype of the insubordinate. He had tried to escape twice. The first time, through a machine that had delivered cement to the camp. They got into the car, started it and, breaking the door, left. He took refuge with one of his cousins, who betrayed them, spying on the Security authorities, who caught them in their sleep.

The second time, they attacked the upper wall of the enclosure, but again to no avail. After each attempt, a re-sentence. The third time, he tried together with Sali Chako. They were able to reach close to the border. But the river had to be crossed. Ahmeti, he didn’t know how to swim. Saliu tried to take it with him, but he couldn’t. Such a thing forced them to turn back when they were almost in the middle of it. They were caught and re-sentenced again. Ahmet by death. They executed the symbol of resistance with the feeling of freedom in their hearts.

Ahmeti was a nationalist with a big heart. When he was in the fortress of Gjirokastra, as an exile, together with his mother, he was visited by General Halim Xhelua. At that time, Ahmeti was very small. When the general saw them, he said: “We will kill this one too, when he grows up.” “Fate” made it so that they were both in the prison hospital.

Halim was heavy. Ahmeti served him until he recovered. – “Why don’t you let me die”?! – Halimi asked him, and Ahmeti answered: – “I am not red-skinned.” I want you to know who the real Albanians are here.”

Sometime later, when he found out about Halim’s suicide, Ahmeti shared cigarettes for his soul. The nobleman showed his nobility, even in such moments. The book has very striking descriptions. In them, the pain of the author is expressed, for the killed life. Longing for freedom, for relatives of the house is expressed.

This is how he writes: “I was very upset. Instinctively I ducked my head under the curl of water and stayed like that for a few moments. A great sadness came over me. I was thinking as if in a fever: – Why are you torturing me so much, oh God?! Why do you give me hope, courage and reason and then abandon me?! Why sit and suffer like this, whole days and nights, without any tomorrow?! Why don’t you say a word to me?! Only one! Don’t you understand how much I’m suffering?!

The water coming out of a perforated pipe flowed over my head, covered my entire face and, after collecting at my chin, fell down into a concrete trough. It seemed to me as if at that moment, I was being washed with all the tears of Albanian mothers. Even with my mother’s tears. With all the tears of the Albanian sisters. Even my sister’s. With women’s tears. Even my wife’s. I was washing myself with the tears of Albanian children. Even with the tears of my son, for whom I had longed.

The author’s meeting with his mother is very touching. A mother who had both her husbands killed. The first partisan and the second, the brother of the “Hero of the People” Asim Zenelit, “accidentally”. A mother whose two brothers had been killed. The first one with the ballistic detachments and the second shot, after the end of the War. A mother whose son had been imprisoned, when Enver Hoxha himself came to visit her house.

This episode reminded me of my mother who came from Vlora to Bulqiza and was not allowed to meet me, as I had been punished, because we had commemorated the thirty-fifth anniversary of the Vlora War, in 1920! Then he was forced to flee with a broken heart, giving the little food he had brought to a Dibran mother who was coming to see her son.

This is how the author writes: What a horror and drama my mother had gone through! And now he was again in the terror of power. My sister was at university and meetings with me, no doubt, put my mother in a very difficult position. The class war was the most diabolical and unscrupulous invention that the human mind has produced in its entire history.

The class war was a prehistoric animal (goxilla) that trampled, trampled, crushed, tore, exploded and destroyed everything. The class war, it was; all against all!

The episode of Officer Ali’s child, who went to visit Dr. Isufi, left a deep impression. The prisoners are amazed at the beautiful and innocent face of the child. This episode reminded me of him with another Isuf doctor, the unforgettable Isuf Hysenbegas, in the Vlashuk camp in 1953. The son of the camp operative, the criminal lieutenant Ademi, was seriously ill.

The doctor visited him, intervened on a prisoner who had oily penicillin, which was very rare at the time, and saved the boy. But the criminal not only did not return the penicillin, but sentenced the prisoner to solitary confinement. It is not for nothing that a popular proverb says: – “As long as the wolf remains a wolf, he wants bullets and not cotton”! But the doctor was a humanitarian and not a savage, like the criminal lieutenant.

The meeting in Kaush with the former academic who had finished in Italy, the participant in the National Liberation War and the commander of the armored vehicles after the war, convicted with the group of deputies, left a deep impression on him. Convicted three times, he told her that he had served twenty years in prison and was now sentenced to another ten years. He was seventy-six years old and he did not know if he would live to finish these years.

At this time, he remembered the story of the first photojournalist and cinematographer in Albania, Makut, (Mandi Koçi), with whom they had been in Kaush when he was arrested. He was seventy-four years old and the court had sentenced him to twenty-five years in prison. In his last speech he said ironically:

– “Put your hand on my heart and sentence me to twenty-six years, so that when I come out re-educated, I will be a hundred years old.”

Episodes follow each other. Each one more beautiful but also more painful than the other. Like a prisoner’s life itself. In these moments I remember the expression of the French playwright Pierre Corneji, in the tragedy ‘Sidi’: “I am young, it is true. But in great people, value is not measured by the number of years”.

Halil Laze left us some time ago, but his life, his literary activity, ranks him among the prominent people of our country. He will forever remain so in our minds. Memorie.al