By Sven Aurén

Translated by Adil N. Bicaku

Part twenty-two

ORIENTI EUROPE

Land of Albania! Let me bend my eyes

On thee, thou rugged nurse of savage men.

Lord Byron.

In the book “Orient of Europe”, the author of the work is the Swede Sven Aurén. They are impressions of traveling from Albania from the ‘30s. His direct experiences without any retouching.

In a word, the translation of the book will bring to the Albanian reader, the original value of knowing that story that we have not known and we continue to know it, and now distorted by the interests of the moment.

Now a little about what these lines address to you: My name is Adil Bicaku. I have worked and lived for over 50 years in Sweden, without detaching for a moment, the thought and feeling from our Albania.

I am now retired and living with my wife and children, here in Stockholm. Having been for a long time, from the evolution of the Albanian language, which naturally happened during these decades, I am aware of the difficulties, not small, that I will face, to give the Albanian reader, the experiences of the original.

Therefore, I would be very grateful if we could find a practical way of cooperation together, to translate this book with multifaceted values.

Morally, I would feel very relieved, paying off part of the debt that all of us Albanians owe to our Albania, especially in these times that continue to be so turbulent.

With much respect

Adil Biçaku

Continued from the previous issue

THE STRIKE SHAKES TOWARDS NORTH

This country has had many capitals. The capital of the new Albania is called Tirana, but before that both Durrësi and Vlora could boast of the honor and dignity of the capital. During the four hundred years of Turkish rule, Shkodra was the administrative center and the governors, through terrible threats and beautiful promises, tried to keep the Albanian freedom-lovers suppressed.

During the 1400s, it was Kruja, the famous city of Skanderbeg, the center of the country. Kruja means source in Albanian. It is a very worthy name, because exactly in Kruja, where the great vein of love for freedom, exploded openly.

Here the warrior was led with the goat helmet, small but triumphant groups, and processed his fiery manifestos. Except in 1478, the city fell into the hands of the Sultan and then it had cost the Turks, almost as much suffering and bloods as all the European conquests together. The first Turkish governor, who entered the defeated Kruja, took the opportunity to rename the city. He called it Ak Hissar, which means “white fortress”. Kruja, the source of love for freedom, would disappear and die.

Exactly now, when we, from the green velvet olive grove, climb the car upwards, towards the city of Skanderbeg, the name Ak Hissar comes to mind. This is so false as to be true at once. The city is white, which is caught near the mountain road, up there. It’s dirty gray. Yes Hissar, fortress, is. With terraces with low houses, castle ruins and fortress walls, hang around the side of the mountain.

He is harsh and repulsive. Skanderbeg carefully chose his residence. I understand very well the difficulties of the Turkish Sultans: that with the primitive means of warfare of the middle Ages, seeking to conquer a city likes this must have been a futile undertaking. There was no other option, against these defenders over the brave, than to starve to death, and this apparently, has been the way, that victory was finally achieved.

But now Turkey is almost retreating, in that part of the world where Ak Hissar belongs, it is called Kruja again. In modern Albania, Kruja mainly plays the role of the relic box. Kruja is the holy city of great memories and does not represent any function in the national economy. 5,000 inhabitants try as hard as they can to trade with the people of the surrounding highlands, but the incomes are small and the population is poor.

The prefect, who awaits us with coffee and “life goes on” in his office, in the ruins of Skanderbeg’s castle, gives me the impression more of a museum intendant than a prefect. In fact he is also in charge of the museum. The government regards the city as a national temple and has banned any new construction beacons that do not fit the old style.

As far as the economy allows, it is intended to set up a clothing museum, where many folk costumes, very different from each other, would be found on display, if it looked like republican hats and jackets, would enter and form a march, no welcome across the country.

I say not welcome, because for the dignity of the government it should be emphasized, that it propagandizes for keeping the nation clean, to the extent possible, in terms of costumes and works of art in general. With all the propaganda, still, the risk is great. The costume museum in Kruja can soon fulfill an important function.

The prefect is indeed a pleasant gentleman, who with great enthusiasm demonstrates what is left of the old Skanderbeg Palace. Not much: some old walls with an impressive thickness, tunnels, wells, old iron doors. As early as the early 1800s, it was learned that large parts of the castle had been extremely well maintained, but Rashid Pasha, in 1832, ordered a major demolition.

Resident prefect, in the former governor’s apartment, which is a magnificent house, with beautiful ceilings and paintings on the walls, with clear and well-preserved paints. Among the best preserved are the defensive walls of the castle area, within which there was room for eighty houses and for approximately five hundred inhabitants. Of course, they were only for the richest and first inhabitants of Kruja, who were allowed to live within those high defensive walls.

The poorest part of the city’s inhabitants were forced to build outside, and this, of course, could be quite dangerous when Turkish intelligence patrols sneak up the mountain. But if Skanderbeg’s men caught such a patrol, so soon the Sultan’s soldiers would rejoin the main army, but in less likable forms. They threw them out of any window of the castle.

This was a fairly large height: 604 meters, to be exact. Kruja Mountain, Sari Salltik, is 1,005 meters and has a plateau section, at 604 meters above, from which the rest of the mountain rises perpendicularly upwards like a wall. On that plateau lies the city of Kruja, impenetrable, isolated and proud.

The mayor is, as I said, a very communicative man. He tells extensively about his city and its special values and finds us a reliable guide, with good knowledge. He also wants to know something about Sweden, the Swedes and the Swedish capital, Copenhagen, with the polar bears and the perpetual winter.

“We do not have any glacier gold in Albania, but on the contrary we have ordinary bears, but it has been a long time since I have heard about any specimen,” he said. But do you know what we have, that I would believe we are the only ones in Europe: wild pelicans! They are in large numbers, especially in the Shkodra area.

-Now we will probably start a small walk through the city streets, he adds and makes a gesture to our guide, but stops by a sudden voice.

Already so early this cloudy morning, I began to tremble for the rain. It has just begun. He jumps threateningly, over the window panes and by order of the prefect; a soldier escapes to the city, to get tents for foreign visitors.

***

On the way down from the castle, the rain gets even heavier. The steep street of the bazaar, turned into a raging stream, like a youthful swirl, dances forward between the rows of houses and inadvertently enter, over the thresholds of the shops. The merchants stick to the tail, around the bad coal stoves, and very carefully, deal with the long-tailed coffee-makers. Wet cats, lick. The roof of the shoemaker’s shelter is inflated under the weight of rainwater.

The sky is dark blue.

We escape to a pharmacy, a small different drug store, where sweets are squeezed between medicine bottles and there you can take powder, against headache, in a paper cup and argue with the pharmacist, over everything and nothing. After we had tried the pharmacist’s coffee, we rushed back out into the storm. And this time we reach the only cafe in Kruja, which attracts its customers with a sign:

“Kursal”.

The devil got this name! It is not enough that the original and attractive capital, has attached to the best coffee, this banal label. Even here in Kruja, in this city, that with such pride and under the direction of this kind of determination, to be called “Nuremberg of Albania”, they could not cope. “Skanderbeg Coffee” would not have been so good, it is accepted. But “Kursal” more than a blaze. This is a death blow. Maybe invite them to Tirana for “Cocktey Mondein”?

So, so bad thank God it is not now. It really seems like a choke when the polite waiter greets us with fluent English and with that the irritating kvasieuropjan moment stopped. This wonderful man, is one of those many immigrants, who after the founding of the Monarchy, returned from the US to the wild mountains, of his parents. He does not invite you for “cocktails” but for brandy and yogurt, which spins white threads, dirty between the mouth and the sahan. He is very nice. In Kruja, on average, a foreigner comes every two years.

As the drinking water turns the brandy into white milk, I pull out a small book, which one of my friends from Tirana put in my pocket, before we left for Kruja. ‘Read along the way’! he begged me, but who can read a book, in the car that is thrown up and down, when the abysses and the twisting turns, come and darken the eyes and suck in the belly. We are not all Albanians. At the turns of Kruja road, Elbasan road, I think it is a straight highway.

Those bookcase covers creak when misused when a page with the title:

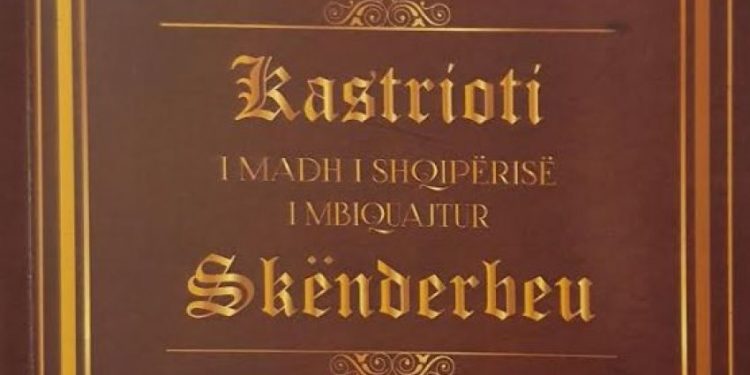

Le Grand CASTRIOTTO Surname´ LE SKANDERBEG

Roi d´Albanie & grand-duc d´Epire Histoire

Stefan Zanovi,, called the writer and his work, was printed in Paris in 1779. Who was the author, my friend did not know. Stefan Zanovi, is never a well-known name, neither in historical discoveries, nor in artistic literature. Apparently he is an old lover of legends and heroism, who during his diligent studies in the library, was fascinated by Skanderbeg’s bravery.

The famous priest of Shkodra, Marin Barleti, and the French aristocrat, the amateur of history, Jacques de Lavardin, helped Zinovic with material, which he could process, a work that he seems to have used with respect and care. It is a small, very fascinating book with a spiritual, French intellectual tone.

Under the proud motto “Georgius Castriotto, secula vincet”, Stefan Zanovi përshk describes the heroic tale in beautiful vicissitudes and in perfect forms. With fire and feeling, he tells about the wars in the high mountains, about the losses of the Turks and the victories of the Albanians, acts of bravery and fiery speeches. At the center of the events stands Skanderbeg, like a granite rock; noble brave, wise, inspiring.

He is a warrior of that type, who carries his sword with him to bed, when he goes to rest, to the castle of Kruja and who responds to congratulations on victories with meaningful words: Do not congratulate me. I have to win. God is the general of my army and I am his adjutant! He welcomes ambassadors with the dignity of a King and the people as a father.

The King of Hungary and the Duke of Bourgon set off on the long road to the mountains of Kruja, their representatives to greet him, as the young Alexander. The Pope grants him, the high order of the Catholic Church, Venice, sends caravans loaded with gold! Skanderbeg is precisely the hope and savior of Christian Europe against the destruction of Islamic armies.

The warrior with the strange goat helmet assures the ambassadors, that he knows his duty and swears to the Church, for unbreakable obedience. But when on one occasion he is offered a Royal Crown, as an outward sign of high dignity, he refuses to accept it. Only after the persistent prayers of the inhabitants of Kruja, he accepts a compromise: he puts the Royal Crown on the goat’s helmet. With that grotesque helmet, he has fought won and the helmet they want to keep.

When Zinovic comes to this point in his story, then the old warrior is ready to rest his head, after four decades of thoughtful work for Albania and the issue of Christianity, the hero’s tale, makes a real appeal. He adds something that can be called the testament of Albanian freedom: a farewell speech, that your fighter dies, he gives to his ten-year-old son Gjon. It is a touching sermon, a Royal life program, reaching classical heights.

“I am on the verge of the grave and a Kingdom will trust you”, says Skanderbeg. “If you can not preserve the freedom of this Kingdom, then you have my curse. “But you have to be able to save it, because the conditions are.”

And while the little boy, standing by his father’s bed, before death, terrified at the weight of this burden, which is placed on the young man’s shoulders, gives him a lesson on the abc of governance.

“My son, you must take care of the flower of custom, because customs are the foundation of the throne. Habits are not an illusion; however, you will surely encounter those who will try to encourage that thought. “Remember that he who interprets such thoughts is a traitor, a traitor, who, in order to overthrow you, tries to make you believe in false ideas, and sooner or later, he will cause your downfall.”

“That ruler, who always resides in his court and among his flatterers, is treated as an enemy and tyrant, by other citizens. Curse alchemists and astrologers, from your circle. And as for those poets who dedicate to you poems and songs of high praise, to convince you, that you are the greatest, most generous and bravest, among the Kings, so give them as a reward, a piece of paper and a pen, with the command to testify of the truth, in their writings. If they can not and continue with their dangerous writings, you must let them know that they will be drowned as poisonous, of the truth and by yourself, you are the defender of the truth “.

“I curse you, if you keep a prisoner in prison, for more than twenty-four hours, without taking him to the investigator, and if you do not see that the trial against widows and children is not given a trial, within eight days. Do not forget to hang white marble boards on all the prison doors of your country. On the boards you will engrave in black letters: Cursed be the governor who hides an innocent, lest his King see him, or for reasons of savagery or stubbornness prolongs the suffering of him, the innocent”!

In this way sound the proverbs, of the warrior before death, addressed to the boy and the friends present, which give him moral courage. Little John guesses what obligations await him now, and all the while growing up, the words of his father’s farewell stick to him like the sword of Democles, which hangs over his head. The mother instills excellent knowledge literally, syllable by syllable. Even his teacher does what he can to keep the will alive.

John, feeling unhappy and anxious, under the weight of responsibility and wise advice, do other effect than expected. Skanderbeg’s son, could never reveal himself, but disappears into obscure history. None of the many who have written about the war, about the freedom of Albanians, have said anything about Gjon Kastriot and the fate of his life. Gjon Kastrioti disappears from the eternal tragedy of being the son of a great man.

But Monsieur Zanovic will take the floor again.

Skanderbeg is therefore dead and is buried in Lezha, near Kruja, where the Turks open the tomb and scatter the bones of the deceased, like a talisman. The Pope wants to canonize him, but the plan fails, for the unwillingness of the tribe to pay those 100,000 ècus, which His Holiness, in the capacity of the general controller of paradise, thinks he has the right to demand as an entrance fee. Around Europe, the news of his death was received with horror and despair. But one who does not mourn is the ruler of the Turks, Sultan Muhammad:

“The news that that Hero of Christianity had died prepared an absurd pleasure for Sultan Muhammad. He jumped off the couch, broke the pipe, knocked down the coffee cups, hugged and kissed his servants. He did a thousand strange things and sat down in the halls: Allah! Allah! Kastriot died… I have no one to be afraid of anymore”!

And then the ruler of all the Turks adds with a sigh of disappointment:

“If it were not for Gjergj Kastrioti, I would have put the turban on the Pope’s head and the crescent moon in the dome of St. Peter’s church!”

With that I ended up flipping through the book about Skanderbeg, by the French writer. But the moment I was picking up the torn old pages of the book, my eyes go to an underlined line. It is a small fragment, from the 20 pages of the speech of the hero of Kruja, about his son and is underlined with a blue pen. Blue feather, in a beautiful volume of 1779!

But when I look carefully at the marked line, I am ready to forgive my friend from Tirana. There are some very interesting words, which he wanted to get my attention. It is a statement, which builds a brilliant current bridge, between the Middle Ages and today, a bridge, in which I from Skanderbeg’s Albania again wander inside the Monastery of King Zog.

Where it stands:

“My son, Rome’s dark politics have often been fatal…”! Memorie.al