By Petraq Xhaçka

The thirtieth part

Memorie.al/ The purpose of this book are to join the efforts made to present the truths and horrors of the communist dictatorship in Albania. The main purpose of the book is not to show our people or anyone else, that we oilmen have been innocent, because this has become known from publications in our press, from foreign televisions, as well as from direct meetings with the International Forum and the Albanian Human Rights. The author’s desire, is that through this story, together with other stories, fight any manifestation in any form, even moderate, that he may have to create a communist society. I think that even through this bitter personal history, the cruel, treacherous and overbearing face of Enverism will appear, that for half a century, held the knife with the tip in the chest of the Albanian people, with a pine eye, intercepting the movements for salvation from the outside, or rebellion of the people themselves, ready to push the knife to the heart, at the first movement. The events are set in the economic fields where it has appeared most strongly, such as the oil and gas industry, where I was fortunate to pour my energies, for a lifetime, and become a participant and witness in those events. All the events that are written in this memoir are true, not only without any exaggeration or embellishment, but perhaps, I don’t know how much I was able to present the terrifying force of the events that took place in that decadent system of socialism, where no there was no human feeling.

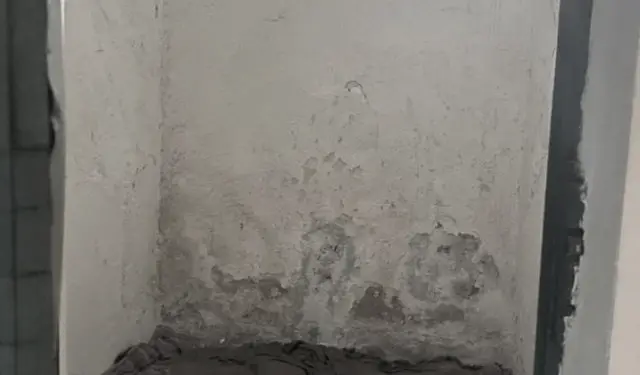

New Prison, Tirana

The completely formal judicial process ended within a few hours and with the announcement of the predetermined decision, we were returned to the New Prison of Tirana. They put me in a dungeon with Mynyri. For the other three colleagues, we did not know how they were arranged, but later we learned that Enriko was in a room with Petrit and Luani was placed on his own. I felt as if a weight had been lifted from my chest: all that anxiety over the possibility of the death penalty had made me almost indifferent whether I had to spend ten, twenty, or twenty-five years in prison. And above all, that terrible marathon, nearly a year long in the investigator, between life and death, had ended.

The first thought, after learning about the decisions, was the family. Now, I would finally see my wife and children, I would find out what had happened to them. According to the law, we were supposed to be allowed to meet the families, but this was violated by the Security and prison authorities, and we did not meet them, not after five days, not after fifteen days, but only after two months had passed.

During this waiting period, to move to another camp or prison for political prisoners, only Mynyri’s family gave him food and clothes. The meeting was not allowed. My family was not notified, and I had no food for two months. But we were not attracted so much by taking food, as by meeting them. We were very worried about their fate, that’s why we asked several times to the director of the prison, to apply the laws in force and organize a meeting for us, or receive letters from our families. Nothing! As everywhere, the laws made the people who ran these bodies. The laws that were written in the parliament were formal and worthless. And no one answered for the violations that were done to them.

The dungeon we had to share with Mynyr Arapi was thick-walled. It had an area of about two and a half meters, by three and a half meters. The height was ample, about four meters, but it didn’t work for us. There was a small window, also without glass, but with a thick lattice of bars. From there, from time to time, voices of people were heard from outside.

It was January and it was freezing cold. I was very cold, and what’s more, I missed the thick sweater, which the investigators in Fier kept, because they were ashamed that I would appear before the court, with that dirty booty. Although I was now constantly looking for it, no one remembered to bring it to me from Fieri. How it seemed, when I complained to the director of the prison and asked them to bring me a sweatshirt, the great cold that tortured me made the prison staff happier and no one gave me an explanation…!

However, this new phase was different. As an immediate reward, I had the presence in the dungeon of my friend, Mynyri. The thoughtful period of solitude ended there in the cruel investigation of the city of Fier. Now we immediately started with our stories of the investigative process, how we had been tortured, how we had accepted the things that were imposed on us, how we suffered in exhausting our fantasies, in order to feed with facts the hostile activity assigned to us by our investigators! There we learned from each other, how the variants of recruitment as foreign agents were created and deleted several times!

For the first time, after almost a year, our faces, bruised by the torture of the cold, from not eating, from spiritual suffering, began to sketch the first smiles. The laughter in the middle of this great crowd was out of place, but nevertheless, it was surprisingly loud, light-hearted, and so hard to believe. Often we laughed with tears, at the stupid things that happened during the investigation in Fier, so much so that you came to believe that these had happened to some others, and we were just enjoying them. Such is life.

Then immediately, our faces were filled with sadness, and we began to cry over the troubles, and especially the heavy consequences on our families, who would not only live surrounded by a fierce persecution, isolated from relatives and society, because no one would dare to approach them. Years later, a former employee of the Security, who had been involved in the oil sector, told me that for two months, in the dungeon where Mynyri and I were staying, they had been eavesdropping on us day and night. Interesting, what else did they want from us?! Did they deal with social studies, with medical trials, or with literary plans, for the dramas of people with scientific values that were wasted?!

Even the little food that came to Mynyri once a month, he shared with me. Only the eight cigarettes of the daily norm, we did not share equally, because he was known as a heavier smoker than me, so I begged him to keep six for himself, while he gave me only two. One day, when Mynyri was taking some food from his personal trunk, he secretly tried to take nine cigarettes, that is, one more cigarette. The policeman saw him and punished him for that day, not giving him cigarettes or food brought by his family.

After a year, we felt the smell of meat, the smell of cheese and good cookies that my daughter had prepared for Mynyri. In those days, he still didn’t know anything that his wife, Lumja, shocked by the strong stresses, had suffered a concussion in the brain and had fallen into a general paralysis of the body. That Lume, whom I knew since her youth, at the Oil Technical College in Kuçovo, a resourceful woman, quite smiling, had now lost all these features, her characteristic vivacity. The terror of the church had its effect on this good and innocent woman.

During the day with Mynyri, we played nines with cigarette butts. Tails replaced stones. One pair were cigarette butts with a filter, and the other half from regular cigarettes without a filter. We marked the squares on the blanket with a small bar of soap that we had sneaked into the sink one morning after bathing. Often times, when we were playing, we were taken for a surprise check by the prison directorate. As soon as we heard the sound of many footsteps, we took the cigarette butts, put them in a corner and answered that we had the waste from smoking cigarettes.

As for the squares on the blanket, we covered them in such a way that even when we lifted it up, they wouldn’t look at them. Even when we were playing our banal game, they eavesdropped on us and thus heard the conversation about the results of the game and came to check. It never occurred to them that we were playing with cigarette butts. So in the prison, even the game of subterfuge was done secretly, with fear, during the phase that we called quarantine, after the court decision, which for us was final, without the right of appeal.

And to think, two old petroleum engineers, who used to sit together, often for hours, bent over geological maps to see the possibility of finding new oil and gas reserves, now sat upside down, on some streaks of soap on blankets on the floor and played under, to spend twenty-five years of a sentence, without any meaning. About three or four weeks had passed like this and one day, a policeman called Mynyri, handcuffed him and took him away. He returned it only after half an hour and I didn’t have a chance to ask anything, because the policeman left him and took me.

In the room that the guard showed me, I saw sitting around a table, eight or nine Security officers, in civilian clothes, and in the middle of them stood the Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs. The policeman had not yet finished removing the handcuffs from my hands, when the deputy minister asked me: – “Do you want to drill in the heavy prison of Burrel, or in the labor camps of the prisoners”? It seemed to me a question that concealed too much caution. – You know that, – I replied. – Now that I am in prison and condemned as an enemy, it does not matter to me where you will lead me. I realized that Mynyrin had been asked about the same thing before, and when I returned to the dungeon, he confirmed it. We puzzled for a long time, for days on end, with the explanation of the question and with the many men who had assembled to ask it to us.

We had not yet solved the puzzle, when one morning, we were told to take our dirty personal trunks and were taken out into the courtyard, waiting to be transferred to another place, which we did not know. We had spent about two months in the dungeons of Tirana prison. All those who would move them were gathered in the courtyard. It was the first time that the five of us oilmen were together. We had gone through together and apart, a heavy ordeal: the investigation, the lightning trial and the isolation in this prison, which we were leaving that day. We had lost our faces, we were gray and we were old.

After two hours of waiting, the auto-jail came to pick us up. It was a small “GAZ”-51 truck, where a quarter of the body was divided as an antechamber for accompanying police officers. And we were put in a very narrow tunnel, half a meter wide and about two meters long. There they arranged all five of us, with all the trusses and of course, with handcuffs. That room was lined from the inside with sheet metal and had a very small hole in the ceiling for ventilation. The hole was too small to bring in enough air and as soon as we started the journey, which was really not very long, we started to feel sick and vomited. The sheet metal room, which was more correct to call a large coffin, except that there were no windows for ventilation, did not even give us the opportunity to orientate where we were going. Apparently, for them we were still not human, because even animals are transported in a larger volume.

The other part, which occupied three quarters of the body, dressed like our part, was reserved for some ordinary prisoners, who were being transferred with us that day with the same vehicle. More people had entered there, and we could hear their screams, they were complaining about the difficulty breathing conditions. They asked to stop the truck and open the door for a while, so that we could breathe and fresh air, because they were sick from vomiting. The police could not stop the car, because the regulations did not allow it. With all the shouting and cursing, with the most banal vocabulary that exists in the human language, especially Albanian, the policemen continued to transport these living beings to the address they were ordered to. With our hands tied, we bumped into this coffin at every turn and fell on top of each other because we had nowhere to hold on. We often rolled on the floor, from a long bench that only had one side, because there was no place to put a bench on the opposite side.

It was lucky for us, that on that first day, the road did not last more than an hour and a half. But the other roads were terrible, – and I’m telling them here, so that I don’t have to deal with the trips anymore, – when in such auto-prisons, people like us were transported on long roads, from Lezha to Saranda, for example. It was a grueling journey, lasting more than eight hours, in a hot summer season, at nearly forty degrees Celsius, completely enclosed, without sufficient air current, for twenty-five people, who saw their spoils being made all the time, or the food we had with us.

No lights in the car, no windows, total darkness in the middle of the day! The small hole in the ceiling, struggling with asphyxiation. On the way, most of them got mad. From the first kilometer, the vomiting and shouting started, because in that darkness and with their hands tied, the prisoners sat on top of each other. All of a sudden, the pushed and the beaten came to take their place, so that no one could see who it was and where it was going. They did not stop complaining and cursing. Some, with a low conscience and forced by scarcity, as they were bound, would steal a blouse or food from another, and he would not notice it at all in the mess. But even the one who abducted did not know from whom he had taken it.

In these hollows, we, the politicians, were again more restrained. I filled the place around me, with the crutches, my legs and those of others, with the sickening vomit that I could not contain. Some prisoners fainted. A man was on the verge of death, and when we arrived, only the urgent and courageous intervention of the camp doctor, who was also a prisoner, who cut the blood vessels with ordinary bread knives, without any sterilization, saved this man’s life the newly arrived prisoner, from this journey to hell. In there, we were traveling thrown, as they are thrown into the big drum of the car, the garbage with different compositions of food, boards, glasses and cardboard.

Handcuffed two by two, you could hear the frequent screams, when one, forced by the narrowness, tried to move his body or arm, and this caused pain to his friend, with whom he was bound by a pair of handcuffs. These were continuous, all along the way, like a rollercoaster that has no end and especially in the turns that are so numerous, on the road between Fier and the village of Saint Vasi in Saranda, which the Party had changed its name to: “Progress”. A camp was built here for prisoners, to work as slaves in the 20th century, for the opening of new lands, for planting citrus fruits. And that was a lot of fun, for the cops and escort officers. This is how life was built in communist societies, where one derived satisfaction from the cries and misfortunes of others.

Like this journey, I had two other journeys, identical, with torture and suffering. We often talked among ourselves, that if one day this system were to collapse, the main culprits should not be put in prison, but should be gathered and walked, in those same auto-prisons, on long and not so long roads, but two or three days, on those winding roads of ours. At the end of those journeys, hardly anyone survived. So there was no need to even put them through trials.

That day came and we did not ask for punishment with such “Tourist” walks. The new state was not supposed to commit such inhumane acts, but unfortunately, it did none of what it was supposed to do. No one answered for all those crimes and ugly crimes that happened in Albania. In our miserable “Nuremberg”, the architects of the suffering of the humbled Albanian people were imprisoned, not to punish them, but to protect them, within the quiet walls of the prison, out of fear that in those fertile times with popular hatred of the dictatorship, someone persecuted, committed some stupidity with uncontrolled revenge. The leaders of the pyramid did not have the chance to try even for an hour, and no more, the punishments with the style of their communist justice, as the political prisoners and ordinary people tried.

The state, in the spirit of democracy, took care with urgency and priority to establish the democratic and humane rules of Western countries, norms that Enrikoja and I had the opportunity to translate in prison, from the books brought from these countries. And these, the new state applied.

Yes, he did nothing to fix the lives of thousands and thousands of political prisoners and internees, who were still sleeping outside in barracks, huts, and under the open sky, after they had suffered from the inhumane laws imposed by the clans of Albanian communism. . The post-dictatorial state was in a hurry, even with an inexplicable speed, to show its humanity to those who had trampled the people, not to those who had been unjustly trampled. Everyone was put into a cauldron with the infamous thesis, that under the dictatorship, everyone had been a co-sufferer, and yes, all co-guilty. And by the irony of fate, my investigators immediately gained the status of accomplice, while I still do not understand how the status of accomplice can be displayed on my forehead…!? Memorie.al