By SIMON MIRAKAJ

The twelfth part

“Camps under the shadow of Tomorri, 44 years of internment”

– Memories –

Memorie.al / I put these memories down on paper after a long period of hesitation. This is probably because the subjects were always fresh in my mind, which followed me mercilessly during the years after the fall of communism. But there comes a moment – when time takes its course – and the images of horror and suffering, came fading to me – almost the suffering passed into oblivion. Then I decided to repeat the most impressive events – first in my mind – until they took the form of these narratives. As dim as these accounts may seem – they create the idea of the harsh reality and misery of the camps.

Continues from last issue

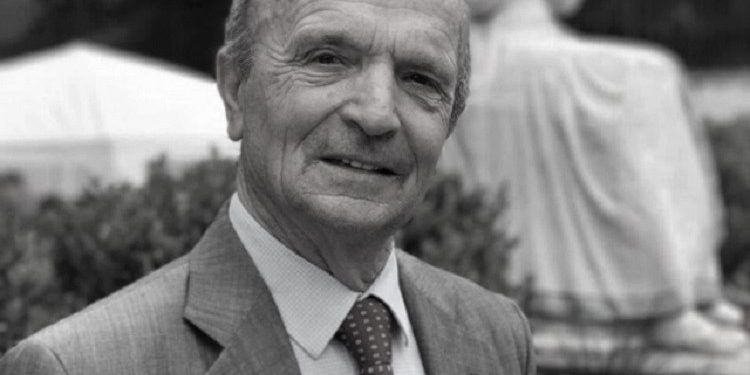

Osman Kuçuku

Osmani was originally from Gjirokastra. He was married to Mrs. Dilfo from Cologne, they had no children. Dilfo had taken care of Vali for several years, until he got married.

Later, Vali grew up to be my uncle. In the 1960s, he was exiled to Savër. After a few years of exile, the Kuçuku couple settled in Lushnje, in the house “Kongresi Lushnje”, property of the patriot Kaso Fuga. Valbona met my brother in the internment camp and married him in 1964. The marriage gave us the opportunity to meet Osman and Dilfo Kuçuku. They loved us and we loved them.

From 1975, Dilfo died of azotemia in the kidneys. Osmani was left alone; he was a very orderly and dignified man. In 1960, a powerful earthquake struck Lushnje. After a few days in Lushnje, the dictator Enver Hoxha arrives, who had been a childhood friend of Osmani, who at that time worked as a worker in the mortar joint. Enver Hoxha goes there to see the measures taken to cope with the earthquake damage and when he was at the mortar joint, he saw a man who looked like a childhood friend.

Osmani saw that he was looking at him and took off his hat, and then the “Commander” recognized him and went and hugged Osmani and said:

“What do you want from me”?

“I don’t want anything, I’m very well.”

The next day, Osmani is called to the Lushnja District Party Committee and told:

“What do you want from the Party”?

“I don’t ask for anything; just give me the front tires”.

When we were transferred to exile in Gjaze, Osmani came once a month, brought us food (because we had rations), like coffee, etc. It has been some time since he didn’t come and we got worried. Sokol says to his sister-in-law (Val): “Go to Lushnje and see what happened to him”. Vali goes to Lushnje and finds Osman lying in bed, after he was paralyzed. He returns to Gjaza and tells Sokol that; Osmani is paralyzed.

“What will we do”? Sokol says to his sister-in-law; “We will take it and make it our service as much as we can, but we should also ask Simon”. When I got home from work, I asked Vali:

“How was Osmani”?

“Osmani is paralyzed”. Sokol tells me; “What if we take it and serve them – what do you think”?

“I completely agree, except for me, I don’t feel like using anything but a shovel.”

The next day, the ambulance arrives with Osman and we put him in the room where I was staying with the children. I went out to the reed hut. Every day when Sokol came back from work, he did gymnastics for Osmani, who managed to get better. In the evening we took the bottle of brandy, Osmani liked to drink a glass. We took the bottle and went to Osmani’s room.

My sister-in-law was preparing some snacks for us. Osmani, with our help, would get up and start drinking. At one point, Osmani takes the bottle, slams it on the table and says:

“E Pal Biba, you made the boys, I’m making them happy”!

Under our care, he improved a lot; he started walking while holding him with a support. After six months, he passed away. We did all the services, while we did the burial in the Lushnje cemetery.

May they rest in peace?

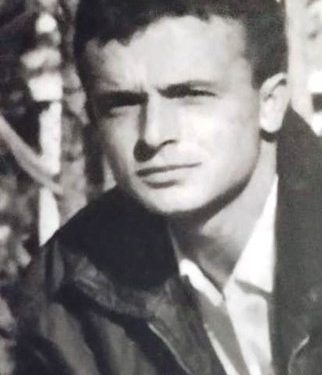

Dede Marka John

Deda is the son of Kapidan Gjon Marka Gjonit. I was with Deda in the internment camp, Savër. While with Kapidan’s family, we joined the internment camps, since 1945, in Berat, Turan, Tepelen, Savër, Gjaze. In Savër and Deda, we didn’t have the chance to exchange conversations, because of our age; we met in the morning and at dinner, when we made the appeal.

Deda, as soon as the communists came in at the end of 1944, he was arrested and kept in the investigator’s cell for three years, so much so that, as Deda told me, that; “When I saw myself in the mirror for the first time, I saw that my hair was as white as snow, I was gray.

“They brought me to court and sentenced me to 5 years, and sent me directly to Burrel prison. Burrell’s prison was really very heavy, but there were the cream of the nation, former ministers like; Xhevat Korça, Mirash Ivanaj, Gjergj Kokoshi, Kudret Kokoshi, Professor Arshi Pipa, Foto Bala. Clergymen such as Father Peter Meshkalla, Hafiz Ali Kraja, etc. So at that time, Burrel prison was, in terms of the level of prisoners, University”.

Deda, although he had suffered a lot, both in the interrogator and in prison, maintained the nobility of the great princely door and had a sense of humor. The place where we made the appeal was close to the club. The salary, from the work we did, was received once every 15 days. After receiving the salary, we went to the store, took the food.

Deda’s Nana used to buy a bottle of brandy with the meals. As I said, after making the appeal, Deda, Fatbardh Kupi and Tomorr Dine, when they got their salary, they went back to the club and drank a glass of brandy.

Nana Mrika was sitting at the door, waiting for her son, when Deda approached the house, her mother asked her:

“But why were you late, son”?!

“I drank a glass of brandy with Bardhi e Tomorri, in the club”.

“But why do you go with my nana, drink brandy with me in the club, my nana bought the brandy and drink it at home”.

Deda calmly answered:

“Eh, my mother, brandy is not drunk with mother.”

When they removed us from Savra and sent us to Gjaze, meeting with Deda was daily, Deda came, I went to Deda. I worked with John, in a brigade. There were times when Deda and I were in a brigade. When Deda came home, he used to smoke. He drank it with qibuk, and yet, we enjoyed ourselves. Most of the time, he smoked tobacco, good tobacco. From time to time we used to say:

“Ded, give up smoking once, because I’ll ban you.”

“When they quit smoking, I get sick.” Deda, after the appeal, did not go home; he stopped at Dinaj’s, or Ismail Spahiu’s, or came to us. The nephew, Gjoni, was different; he used to leave the house, very rarely. About the grandson, Deda used to say: “This grandson of mine, I don’t know where he came or went.” You tell uncle Selamiu this.

We had played chess. Gjoni was playing with Afrim, uncle Selamiu’s son, it was past midnight. “My nephew, you don’t know where I came from; you don’t even know where you left”! Then Deda said to uncle Selamiu:

“This nephew, after the Spaçi revolt, knows that from Vermoshi to Konispol, the arrests began.”

Every day we went to work, hugged our brother (Sokol), and hugged our children, said goodbye to our sister-in-law (Valin), because we didn’t know if we would return home. This uncertainty lasted for eight years, from 1973 to 1981.

We had bought from a military bonnet and had them cut at the tailor. Every day we took them with us, even in the middle of July, we threw the hoods over our wings. This is because former prisoners told us that it is cold in the dungeon.

The last one was arrested, Fatbardh Kupi, in October 1981. After we made the appeal, I talked to Deda and told him:

“Dad, I lost the lottery and got arrested, how should I stay”?!

“Nothing, you have to accept me, you have to be afraid, you have to put up with some bullies. But if I tell you, it’s easier for them to arrest me, because they have the file ready”. After a few months, when I was returning from work, we were told that Deda was arrested. After two months of investigation, he was brought to court, sentenced to 10 years in prison, with a blank slate. One of the accusations was that; you said that Germany is more developed than Albania. Several people appeared as witnesses in the trial, whom Deda had never spoken to, because they did not belong to our class.

Deda had not spent the year in Ballshi prison, when Sokol saw a dream and told me that; “Deda, I don’t deserve more than two years in prison.” Indeed, Deda was caught by the 1982 amnesty and was released (after two years). We had gone out on the road, waiting for him, it was a great joy for us. The next day we went to his house, the questions started:

“How do you leave Moses, etc.”?!

“Mojsi,” said Deda, “was very upset, and it was not his fault that he had left his wife with two small children.” We were walking one day with Mojsi, in the prison yard. He was upset, while I told him: “O Mojs, thank goodness we went to prison, because we ran out of channels”! Moses laughed.”

“What do you say, Ded”?!

Deda has passed away. He will be remembered with fondness and respect, Deda was a true Prince.

Deda used to say: “Those who came out untainted by the communist dictatorship, they are the best people, they are the real heroes”. Deda was one of those heroes.

When the release was communicated to us. July 4, 1989

The approach of the hot month of July teases my memory, which races to catch Tuesday, July 4, 1989. This day cooled us down a bit from the scorching heat that July had brought. Always the hope for freedom, missing for decades, was present in our soul. Now it was closer to reality than ever before. The evil empire is crumbling.

My brother Sokoli and I had completed 44 years of exile. You were briefly explaining what exile means. International begins with the word appeal, which means call. So; we appeared twice a day at the appeal. Which was usually done to us by a police officer from the Internal Affairs Branch? There were frequent cases when we made the appeal three times a day, when delegations came to Tirana or on communist holidays. Without explaining the other psychological and economic pressures.

So that’s the internment. Forced isolation and hard physical labor to survive. We were sentenced to exile every five years. On June 27, 1990, we completed the ninth quinquennial, which began in June 1945. They were very accurate with the dates. At the end of June 1989, the person in charge of the appeal, a very nice guy named Vangjel, called me and brother Sokol.

“Rexhepi is looking for an operative”.

We thought it was time to inform us of the release before the deadline. That the date was correct, June 27. We went but not very enthusiastic. After greeting each other, he took out a letter from his pocket and began to read it. “The Internment and Deportation Commission met and decided to increase the sentence by another five years.” “Agree, sign”.

“We have never agreed. You came early. We will complete the sentence on June 27, 1990”.

We left, that was five ten. We were not upset, because we saw and felt that communism was giving life. But the fear existed, we knew their wickedness well. On that day of July 4, 1989, the brigadier had assigned me to work in the threshing floor, together with Gjon Markagjon, in the wheat return.

It was dusty work. The floor was paved with cement, adding to the heat. From time to time, we would sit down and discuss the situation that was happening in Eastern Europe. “What about us, whatever happens”?! That was the question.

The red emissaries shouted; “We are not in the ‘Warsaw Treaty’, we are not east”. It was getting close to the time to leave work. We left for home. After I washed myself with the Bottle water that we had placed outside, I went inside, lay down on the minder, to rest. Like sleepy, I say to Sokol; “More than anyone, he called; o Sokol”.

“Let me call you again.”

Before Sokoli finished his speech, the person in charge of the appeal, Vangjeli, appeared at the door.

“I have come to tell you good news” and your eyes filled with tears.

“You, Sokol, you, Simon, have been released. A major officer from the Ministry of the Interior has arrived and will inform you of the release. Please, pretend you don’t know anything.”

“What about the others”? We asked!

“All of you have been released, with the exception of Xhevat Tarusha and Gjon Markagjon, but they will also be released for maybe three months. We will all gather at the place of appeal, and then we will go to the office of the People’s Council. You will be notified of your release there. I’m going to inform the others.”

The sister-in-law brought him a Turkish delight, he took it and left. We were a little dumbfounded, the sister-in-law’s children were crying with joy. We all came together at the target, the place where we were making the appeal. Ded Gjon Markagjoni, Tomor Fiqiri Dine, Sazan Fiqiri Dine, Xhevit Hamit Matjani, Sokol Pal Mirakaj, Simon Pal Mirakaj, Xhevat Tarusha e, Gjon Markagjoni. We directed you to the Council’s office. We went inside, nodding to the head of the country.

The Council’s office had a table and benches, we sat there. At the table, there was the secretary of the party, the chairman of the Council, the chairman of the “Democratic Front”. I was looking at them attentively, one uglier than the other and, uglier and barren black, they had a soul. Their attitude towards us had changed. They were rather worried about our attitude towards them.

They had started telling us that; “We knew you were good people, but we had the instructions to fight you. We are not to blame”, we just listened to them. Those dukes knew something about their system that was giving them life, from the meetings they held. The Secretary of the Party took out a cigarette and offered it to us from a cigarette; those who drank it lit it. At this moment, the door opens; the pariah is fled on foot. We didn’t move, we didn’t know him, but we assumed that this would be the major officer, that behind him was the operative and Vangjeli. He took a seat in the chair that was waiting for him.

“Hey, how are you”? – But we didn’t answer you at all. Meanwhile, Vangjeli took out the appeal list and called the names, to confirm our presence. The officer who came from the Ministry of Interior immediately stands up. He was dressed in civilian clothes and with a pair of black glasses which he did not remove from his eyes; he began to read the letter;

“The Internment and Deportation Commission met and after considering your good behavior, decided to remove the measure of internment, releasing you.” How soon we changed for the better:! That on June 27, this commission gave us five tenths of the sentence, as class enemies! “How quickly we improved”, I said to myself!

The major officer began by reading the names. He paused on his feet, thinking we would thank him for this decision. There were rare cases, when they were released, out of joy they said: “Thank you to the Party”. He seems to have understood that, if he stayed on his feet all day and all night, that thanks would never come to him, he continued:

“From this moment, you are free to go wherever you want within the Albanian territory. I have one more order, don’t get involved in politics, you can leave”. We came out, again without shaking hands, but telling you; good day. Memorie.al

The next issue follows