By Niazi Nelaj

The tenth part

Memorie.al / Expelled from the Soviet School of Aviation, with dreams cut in half, part of the group of student pilots, who had studied for a year in the city of Bataysk, on January 8, 1962, after a “hell” cruise ”, with a cargo ship, we arrived at the center of China’s Third Military Aviation School in Chin Zhou City. It is located in the “heart” of Manchuria; at that time there were about 200,000 inhabitants. Without any prominent industry. A city with 2-3 story buildings but paved roads. The terrain around the city was plain; next to it are the Western shores of the Yellow Sea. One of the values of this city was the fact that it was the center of China’s Third Military Aviation School. My going to this school and that city was a lucky chance. In the list of 7 students of our course, which included: Adem Çeça, Dhori Zhezha, Mihal Pano, Bashkim Agolli, Andrea Toli and Sherif Hajnaj (Bracki), my name, Niazi Nelaj, was included, quite by chance?

– At the Chinese Military Aviation School –

Continues from last issue

A “bump” hatched in the aviation military hospital in Çhang Chunit

One day we happened to be very close to each other, and she took the courage to speak to me first. He knew that I communicated in Russian, therefore, in a broken Russian and in a voice that did not hide the emotion, he addressed me with the words: “Hoçu izuchat russkij jazik”! Which means “I want to learn the Russian language”? I wanted to introduce ourselves, so, not without purpose, I asked him: “Qao shë mo minxë”? i.e.: “What’s their name”? The language I spoke was also in pieces but she understood the essence. The girl replied: “Hey, Miss Sen – Xiao Sen” and added her last name: Sen Shu Sen. Of course, I told him my identity.

He was trying to figure out the hieroglyph that belonged to my first and last name. As happens in these cases, in order to stay as long as possible by her side, I asked her about the work she did in that hospital. Without thinking, she answered that she was studying to be a nurse. I told her my specialty and she, as a sign of satisfaction, said: “Mon kao sin”. Which, in our language, means: “I am very satisfied”! We continued to communicate; some in Russian and some in Chinese. When words were not enough, hands and feet came to our aid. To my surprise, even though this language, without sound, we understood each other.

As it turned out, the teenage girl enjoyed the acquaintance and company of me, the boy from a distant country. I don’t hide it; I also liked to stay as long as possible next to her. Before we parted, in the lobby of the first floor, little Sen, quite unexpectedly, instead of shaking my hand, as we do, and greeting me with a: good bye, said to me, in her own language: “Under pu under xao hao pangjou”? I didn’t know the Chinese language, but I knew those special words. They were words whose meaning made the boy or girl to bond with each other with close friendship.

Sweet and meaningful words, said not without purpose. I was surprised but I didn’t give myself away. Where was the surprise? There, in distant Manchuria; thousands of kilometers away from my home village, a 16-year-old Chinese girl was proposing to me. With the frankness of character and age, tempted by a sudden tear, I recalled that strict and unequivocal law which we were read on the first day of our arrival at school, according to which the marriage of foreigners with Chinese girls was forbidden.

I thought about the many difficulties and obstacles that I would encounter on the way, however I did not refuse the girl in her pure request. Okay, I said; Xiao Sen, I will help you learn Russian and you will teach me to play table tennis. They don’t say for nothing that “chance is the king of the world”! That’s how it happened and we both got connected. We started playing ping-pong more often and talking in the corridors of Changchun Aviation Hospital.

This fragile platonic relationship did not go unnoticed by the jealous locals. When we played ping-pong, the locals, gathered around the table where it was played, laughed and cheered, clapping their hands for no reason. When they saw us talking in the corridors, they surrounded us and shouted all hypocrisy. To go outside the territory of the hospital, together with the Chinese girl, practically impossible.

Curious jealousies accompanied us every step of the way. I wanted to meet, but there was no way or where? White-faced, big-nosed; I had also left a mustache for my beard; I immediately caught the eye, like the “kau balash” that they show in my village. The difficult situation that was created for me was eased by my new translator, Petja, and a Chinese officer, with the rank of general, with the duty of division commander. Here’s how it happened:

A Chinese pilot, whose name was Petja, came to the hospital where I was hospitalized. He flew in vintage TU-4 bomber planes with propellers. He suffered from a lumbago, which, in China, was quite widespread, especially among helicopter pilots, drivers, pilots flying low-speed bomber planes, and was considered an occupational disease. We were admitted to the same ward and treated with the same methods.

The common problem, mastering the Russian language and living in the same apartment building made it possible for us to get to know each other. Petja was originally from the Uighur Autonomous Province. His mother was Russian and his father was Chinese. He knew the Russian language better than I, and had mixed facial features; he looked like part Asian and part European. I liked his calm nature and tolerant character. He accompanied me everywhere all the time.

There was interest in eating together, in the canteen, and he was treated with the same food as me, who was “privileged”. Upon arriving at the Petja hospital, my “tracker” was no longer seen in that hospital environment. The hospital administration, fortunately for me, removed the headache-inducing nuisance with his feigned and disgusting behavior. He returned to the Aviation School and I remained where I was, in the hospital, in the company of the pilot with the strange name for a Chinese: Petja.

My new friend, professional colleague, Petja, one day took me to play cards in the apartment of a Chinese general and introduced me to him. The general was a fat Chinese man, he could hardly breathe, large and with a big head, with the duty of division commander. His age was about 40 years old and he was called “babajan”.

Since the unit he commanded was stationed in North Manchuria, along the banks of the Amur River, which separates the two countries: the Soviet Union of those years with China, the general had learned a few words of Russian and wanted to hang out with me. . Maybe because of the profession I had chosen, maybe because of my age or my country of origin, as far as I know. He pretended to know Russian; in fact he had learned some general words, which he spoke with a Chinese accent. In China, at that time, the cadres of his series were treated differently, which was noticeable, not for the better. My young acquaintance, despite the obvious age difference that separated us, invited me to his apartment to chat and play cards.

In those days playing cards was forbidden in our country. If you were caught playing gambling cards, you paid dearly and you were guaranteed jail time. In China the card game was very widespread and cards were sold quite freely. Their favorite card game was: “Njanja” which means princess. The one who won the game was declared: “Huansha”, prince. Everyone aimed to become a prince. The general’s apartment was: an anteroom; one room and the corresponding annexes. The general’s apartment had its own entrance.

In his room there was a double bed, heavy armchairs and other expensive equipment. The hall was large, furnished, also with heavy armchairs. A local worker served in his apartment, which took care of the environment and the general. The teenager Sen Shu Sen, my new acquaintance, who wanted to learn Russian, also entered his apartment. He was well aware of my relationship with the nursing student. I entered his “house”, together with the bomber pilot from Uyghur, as a friend of General Barkalec.

One day I went to the general’s luxurious apartment, alone. He had invited, at the same time, the teenager Sen. She came somewhat timidly, and when she saw me there, she was happy. At that moment, I did not think that the meeting was something planned by my general friend, but I took it as a coincidence. The fact that the translator Petja was not present left me with a taste of doubt. However, before the meeting with Sen, the others did not fade away quickly. We would have a shelter to talk to and the protection of a Chinese general.

Student nurse Sen Shu Sen sat on an armchair in the hall with me next to her. The general came to the hall and found us holding hands. Instead of the usual greeting, “Nji hao”, the general, in a lame Russian, said: “V Kitaj, mozhno: chut – chut”! That’s what the major officer said and went back to the room. I realized that in China, in relations with women one should not overdo it. This was related to that famous law that forbade the marriage of foreigners to Chinese women. The teenager Sen wanted my friendship but, if she caught the eye of the authorities, she was threatened with dismissal from work (school).

However, our “shelter” in the general’s apartment and his protection were indeed offered to us, but they were not safe. Our meetings could not escape the observation of the attentive Chinese who filled the corridors of the hospital. Little Sen was like a beautiful doll. She had just hatched, like a bud, full of hidden feminine graces. We stayed for a while, on the armchairs of the Chinese general’s hall, and talked, in low voices, about general things.

We made platonic “love”, looking at each other, sweetly and not without interest, while our “quality guard” pretended to read the newspaper. Under those conditions, I felt happy. I managed to caress, lightly, her long braids, beautifully woven, which fell down to her hips. The girl laughed and laughed, without a sound, without stopping. We were both drawn to that adventure, without beginning and without end. We were both burning with an internal anger, without being able to tell each other what was bothering us. I had heard and read about platonic loves; in Chang Chu I “tasted” the good feeling and the “bitterness” that it gives you, when it does not materialize.

One day, the girl’s mother came to the hospital. A provincial woman, middle-aged and with a daughter’s body. There were no braids but short cut hair. It was not his chance to have small legs and a big body. Walk normally. He was wearing pants and a black sweatshirt. They both looked alike, like two drops of water. I found both of them, mother and daughter, on the underground floor of the hospital building in a labyrinth where a metal container of several tons had been placed, where they were filling warm water to drink, in a special tap.

I went to that place not by chance and found them with thermoses in hand. I spoke to the young girl and greeted her companion. She said something to the mother, in “short” language, in the Ljao Nin dialect, words that I did not understand. Although I listened, out of curiosity to learn something from the dialogue between them, I did not catch a word. Women had their own “code” of communication. From what I saw outside, I understood that I had liked my mother. I heard him say to his daughter: “Hao Khan”, in an understandable voice, so that I could understand. The words I heard in Albanian can be translated: “Handsome”! Xiao Sen introduced me to her mother as her friend. The young woman extended her hand and I shook it, friendly.

The environment where the presentation took place had a large load of people. Many local women and men came in and out, with thermoses in their hands. We had to part quickly, even though we both wanted our time to be unlimited. I finished my treatment and returned to the Aviation School at Sui Xun Air Base to my fellow students. I did not hide from my friends what happened to me. I had no reason not to show them the incident. I did not sell mind but I told the truth, as it flowed. I experienced the lucky occasion with all that fate brings to the door, without exaggeration and without abusing the kindness of an immature girl. My behavior could only be like that.

After a period of time, I went to that hospital again, to see the effects of the treatment, but also to see my friend. I looked for Sen but couldn’t find him. He had been discharged from the hospital. Maybe as a punitive measure, for our relationship, however it worked. Maybe for other reasons. I was walking, near the entrance of the hospital, one day I saw Sen, coming, in the middle of a group of 5-6 friends. I stepped forward to catch her eye. He saw me and I saw him, in passing, walking. As in the beginning, and at that moment, she spoke to me first.

As if caught in guilt, to break the silence of that moment, which seemed too long to me, the girl stuttered: “What stopped me?” Her question summed up every word left unsaid; its meaning is: “What happened to you”? I’m sick, I said, – in response and I didn’t hang up. I realized that I felt something for that young teenager. This is where our unfortunate relationship ended and we never saw each other again. After all this time that has passed, she has probably “slipped”, like me, and it is not known where fate hit her. However, into my youthful world the Chinese teenager accidentally entered and exited. The fact that I remember it even now is not meaningless.

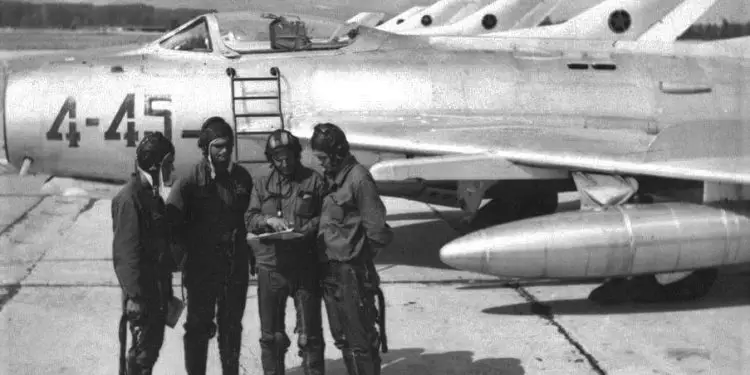

At the end of 1962, when Manchuria had a harsh winter, with Siberian temperatures but no snow, at the Sui Xun aerodrome, located on the edge of the Yellow Sea, we started piloting flights with jet training planes, ‘Mig-15’. Of the students of Batajsk’s group, there were 5 of us left. The sheriff had left for Peking University; Misha was at school with us, but the medical board had declared him unfit to be a pilot, and he postponed the time as much as he could. However, he was treated the same as us; even though it didn’t fly. We were divided into flying groups.

I was assigned to the same group as Dhori Nasi Zhezha. An adult but unmarried Chinese man, Liu Shë Mo, was assigned as our pilot instructor. Small in body and “slippery” in the face, like our “Nephew”, our Lju, in terms of flying skills, he was one of the best. Precise, calm, extremely correct, both on the ground and in the air, he gave us everything he knew, made us fighter pilots. I have fond memories and special respect for that man. He, without ego, with the chaste simplicity of a pilot, sacrificed enough to make us what we became.

In all the multitude of values that we saw in those extraordinary people, the organization of the flight day is special and worth remembering. Our case was unique and they had studied it in detail. We were foreign students and did not speak Chinese. This fact created a reasonable gap which, by no means, could be ignored. We were flying over the sky of another country, which we did not know very well.

We were novices, both in age and profession. Our inexperience could bring unpleasant surprises. A partial or complete loss of orientation in the air could bring potential danger and cause serious consequences. The plane we were flying with had relatively high speeds. It flew near the state borders with other countries and it was possible to accidentally cross a state border. In the air there is always the risk of a special event (breakdown) and the lack of mastery of the language deprived the student of the opportunity to receive verbal help from the ground. etc.

To precede these phenomena and others similar to them; the organizers of the flight day had found suitable, unique solutions. Recognizing the value of the pilot’s communication in the air with the flight leader, on the ground, next to the latter, one of our Russian translators was constantly standing. Of course, the one who had the best command of Russian, who had sufficient knowledge of flying and who had comprehensible and sweet diction? The best find was the translator originally from the Uyghur Autonomous Region – Petja.

Maybe another time I will raise this major issue; the interesting topic of the role and place of the air traffic controller. With us, Petja knew both languages well: Russian and Chinese. He had the ability to quickly process what the air traffic controller told him, conveying it concisely and clearly to the pilot in the air.

The eloquence of his voice and the accuracy of what he transmitted made the pilot more courageous and optimistic. When there was an emergency and it was necessary to intervene quickly, Petja took the microphone from the flight leader’s hand and, on the spot, made a quick and accurate translation with his mind. This was one of the security measures for our flights, but not the only one.

It was the turn of the transit flights. We had to leave the airfield at greater distances. For safety reasons, the route was chosen to pass through Mongolia, which was considered a safe place at that time. But, to have more security, the Chinese had organized Chineseness. 1000-2OOO m. above the altitude at which the Albanian student was flying, an instructor was flying to whom the locators were constantly reporting on the location of the plane with the student on board.

In addition, this instructor, from the height at which he was flying, had all the opportunities to observe the plane(s) piloted by Albanian students. The “guard” instructor took on a special role in case the Albanian student lost his orientation and could not find his aerodrome. In this case, the “guard” approached him, spoke to him, came forward and instructed him to follow him, until he found and recognized his aerodrome.

The airplanes with which we, the Albanians, took to the air were among the best in terms of aerodynamic characteristics, they had calendar resources within scientific norms and, what should be emphasized, they were prepared and controlled with great responsibility. Not those other planes were launched without being prepared and checked, but with us the attention and dedication of the technical people increased. This measure was for the safety of our flights. Even the ground, radio-technical means that ensure the flights, on the days when we flew, were put to maximum efficiency and the plane that the Albanians were flying with was monitored multiple times. Memorie.al

The next issue follows