By Aldo Renato Terrusi

Part eight

Accueil

Memorie.al / Fiumicino Airport. Alitalia’s ‘MD 80’ plane is ready for flight. It’s Saturday, November 6, 1993. 11.25am. The commander received approval. The flight attendants remind us once again to fasten the seat belt. The two engines are brought to maximum power, while the noise becomes muffled and deafening. Buttons and controls are tested one last time according to flight procedures, the brakes are released, the faster and faster movement begins, the acceleration slams the passengers into the back, the plane takes off. I feel an invisible force lifting me up that leaves me suspended in the void. I look around to see if the other passengers have the same feeling as me. Some read, some look out the window, some are indifferent, some barely sit still and some, frozen in their seats, let their fears show. With a wide change of direction, the plane rises in altitude and heads towards the radio beacon of Bari, then straight to Tirana, our destination.

Continues from last issue

On Radio Tirana, on that Monday, June 10, 1940, a voice echoed:

Warriors of land, sea and air.

Revolutionary black shirts of Italy, the Empire and the Kingdom of Albania!

Keep an eye out! A clock marked by fate is ticking in the sky of our homeland. The hour of irreversible decisions. The declaration of war has already been delivered to the ambassadors of Great Britain and France.

Warriors of land, sea and air! Black shirt.

Italy entered the war.

An icy shiver ran through the veins of Aurelia and the entire family. In a foreign country, in anyway uncertain conditions, the problems of survival would multiply. I was 19 years old, I was called up as a soldier in the Italian army based in Tirana. Fortunately, I did not become part of the fighting guilds. I was enrolled in the ‘605 GAF’ Company as a border guard between Albania and Greece, near a place called Milot. Without a single scratch and without firing even once against the enemy, I finished my military service with the rank of captain.

While on guard at Santa Barbara, at the camp’s gunpowder depot, I called ‘halt’ because of a suspicious movement behind a bush and headed in that direction. An exhausting shriek pierced the night, returned the silence, and the comrades ran, but after a ‘reconnaissance action’, they discovered that the unfortunate was a wild pig, that in the following days was destined to honor the canteen of the small garrison. One day after this incident, a furious villager came to the camp, which was generously compensated in food and money, so he returned satisfied to his home.

It was the first days of September 1943. Among the superiors, a certain concern was visible; an embarrassment that they tried to keep secret and that had caught even George Ponte, the captain of the militia and the appointee of the secret services. George had confided to Giuseppe the idea of returning to Italy an hour ago, because things, from a military point of view, were getting complicated.

In the premises of Counterintelligence, the Italian capitulation in front of the allies was mentioned as a possibility. In such a case, anything could happen, and especially a fierce battle was predicted on the part of the Germans, who had never trusted the Italians. Many officers had escaped by ship clandestinely, others regularly. It was better to run for the rescue before we were trapped.

That conversation sparked a dramatic alarm in Xhuzepja, because he became aware of the conditions in which, within a short time, the civilian population in Albania could end up. Giuseppe understood that the words of his friend George meant: Leave, take your family and return to Italy, it’s not too late! But the sense of duty towards the bank was stronger. He protected him to the end, he could not abandon his employees, and he could not run away like a man.

From then on, George was no longer alive. A few days after the dramatic conversation between George and Giuseppe, on the afternoon of September 8, at 19.45, Badolio announced the signing of the armistice with the allied powers. The Italian community breathed a sigh of relief: after months of tension and fear, the war was over. Huddled in their apartments, the Italians erupted in waves of joy.

Unfortunately, in Vlora, the battle began, both between the Germans against the Italians and the Albanians, as well as the guerilla between two armed Albanian groups: the National Liberation Movement and the National Front. To all these, blood feuds between different local families were added.

The civilians, including Xzepe, could not even have thought of the tragedy that was approaching Albania, especially the Italian soldiers. It had not ended for everyone, on the contrary, for many eyes a long ordeal was just beginning at that time.

Initially, in the military zone of Vlora, the troops did not seem alarmed. As time passed, older soldiers began to arrive, no longer wearing black shirts, but dressed like everyone else – in gray and green. It soon became apparent that the garrisons no longer received directives and turned into a large abandoned herd.

Gunshots could be heard in the distance followed, from time to time, by explosions of hand grenades; echoes arrived, but they did not evoke the feeling of immediate danger. On the contrary, a short time later, armed Germans surrounded the department; soldiers with light weapons ordered the Italians to remove their stars and surrender their weapons, then lined them up and sent them to assembly centers. They became prisoners of war without being able to fire even once.

Himara, Saranda, Porto Palermo, Berati, Gjirokastra, Burreli, Fieri, Kruja, Korça, Tepelena, are the names of other shelters where the young Italian soldiers experienced a tragic experience within a few days: they were shocked by the defeat of the army, by signing the armistice, fearing the situation as an enemy in front of the former German ally and having to quickly decide which side to take. In the greatest confusion, frantic voices read declarations, various calls and orders to line up and go to the ports, where they would wait for the ships that would take the Italian troops home.

In each of these cities there were thousands of desperate soldiers ready to surrender to the Germans, convinced of their safe salvation, promised by Nazi propaganda. On the contrary, it was the Albanians who came to the aid of the abandoned Italian soldiers, fought that those men, who until then had been their enemies, could escape and take up arms with them against the Germans.

How enemies the Italians and the Albanians had been until a little while ago is proven by the fact that only at the end of August 1943, a 40-day-long cleansing operation was completed in the entire Albanian south. Hundreds of kilometers had been set on fire, villages burned, villagers and shepherds shot, women raped. The operation was directed by the divisions ‘Florence’, ‘Areco’, the mountaineer and carabinieri battalions, and, with particular zeal, by the shirts of the ‘Mussolini’ battalions.

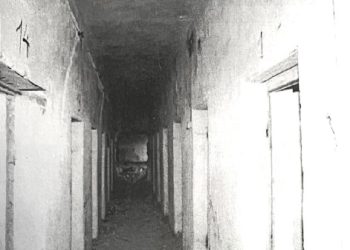

Dozens of internment camps were set up all over the country where the anti-fascists were locked up and by the end of the war Albania had lost 28 thousand people in its liberation war. Not many days later, Radio Tirana broadcast the news of the tragedy in Kefalonia, conveying the deepest horror and concern.

Kefalonia was occupied by Italian troops on May 1, 1943, as part of military operations for the possession of the Peloponnese islands. The organization of about 11,000 people was commanded by General Gardini.

The session of the Great Council of Fascism on July 25, 1943, dismissed Mussolini and formed a new government headed by Marshal Badolio. When Hitler found out about this, he sent a contingent of 2,000 soldiers as support for the Italian troops stationed in Kefalonia. Among the ranks of the Italian army, distrust prevailed and, in some cases, even rebellion: there followed a series of uncontrollable events, misunderstandings, indecisions, denials, which led the commanders to a total disorientation and the troops to a slow disintegration.

In the end, the Italian government itself sought to maneuver on two fronts: on the one hand, it reassured the German allies, telling them that nothing had changed, on the other hand, it examined the possibilities of surrendering to the Americans. On September 3, the unconditional surrender to the allied powers was signed in Kasibila – formalized only a few days later, but Hitler had certainly been informed about this before. On September 11, the German command ordered General Gardin to surrender and lay down his arms. After that, there were days of feverish negotiations with Lieutenant Colonel Hand Barge, and when General Gardini finally rejected the German ultimatum, events took a turn.

The battle began

German aviation with its Stukas began bombing the weak Italian defenses. About 2,000 dead within a week. A trap with no way out. General Gardini, with his commander by his side, asked for surrender. On September 22, this was accepted and the delivery of weapons also began.

The savagery and cruelty of the Germans had not yet ended. While all the Italian officers, led by the commander-in-chief Antonio Gardi, were shot and their bodies were thrown into the sea. Another 5,000 disarmed soldiers were shot and massacred in one of the most horrific massacres of the last war. Many were imprisoned, others tried to return to Italy by any means, and many others joined the Yugoslav, Greek and Albanian partisans until the end of the war.

About 50 thousand Italians fought in the various liberation movements of Greece, Albania and Yugoslavia. That’s all, if not more; they were dissolved in the local societies: they were repatriated only a few years later. In Vlora, there was a great show of solidarity among the residents: thanks to this solidarity, many Italian soldiers returned home, escaping the purges and expulsions.

Emma was very active: with the help of some other brave people, she had founded the ‘Garibaldi’ circle in Vlora and was elected as its president. Fund-raisers were organized to buy clothes, shoes, etc., and to save many straggling young soldiers who had nothing. Two of them, especially the officers of the carabinieri, Federico Taliani and Carlo Verdi, were welcomed in the cantina of the villa where Emma lived, next to Giuseppe’s bank. For the generosity and selflessness shown, Ema later received an official acknowledgment from the Italian authorities.

Italian civilians were surveilled, subjected to interrogations, raids and confiscation of their property. It was very difficult to come out. Near the AIPA Company, two Italian workers were massacred and the director, engineer Balsamoja and the delegated administrator Rovigati, very dear friends of the family, ended up in prison for several days. Tragic news had been arriving for a long time from the Greek-Albanian front; the soldiers captured and deported by the Germans to Germany were in the thousands.

We hadn’t even left Tirana for an hour, when the first houses on the outskirts of Durrës began to appear. The town has a modern appearance, with modest car traffic: some are only recent, others extremely old. Many busy people moved between the many shops of the center. The traffic is quite chaotic, with undisciplined drivers for whom road signs are just annoying urban decorations, and cyclists enter everywhere, returning the insults of drivers and pedestrians one by one.

The buildings we see around us are huge decadent mansions, breathless from recent satellite dishes, and almost all the windows are overflowing with a multitude of dirty clothes. The visual impression is that of a colorful and abstract painting. Perhaps Picasso could not have done it better.

In the port, the number of bunkers is, possibly, much greater than we have seen so far: it is barely possible to see the sea through the narrow spaces between these war monuments. We ask the driver to stop and wait. Toli does not get out of the car to accompany him until we return.

We see barbed wire surrounding the port area and soldiers on war alert, standing guard on the pier. There are also soldiers from the Italian contingent who supervise the area. We want to come closer to greet them and show them our gratitude, but we think well: this action can be misunderstood.

We walk avoiding obstacles to the “Iliria” hotel and near the silo where our family lived its last days in Albania, before going to Vlora and then leaving by boat for Italy. I read in my uncle’s eyes a mixture of longing and anxiety about these memories. We sit in a bar near the hotel with a circular and classical shape from the fascist period.

There is a good aroma of grilling, we order Coca-Cola and grilled food that we find very tasty. Before us rises a massive tower with battlements, from the time of the ancient Roman occupation of Epirus; it is very similar, considering the dimensions, to the Mausoleum of Cecilia Metela in Ancient Appian. I think that if Rome had been so strong, and the conquered countries had become a democratic confederation, this sea which now divides nations and continents might in one mind have been the nostrum sea, and the Mediterranean peoples might have lived in peace.

Between the old hotel and the tower, in later times, a monument to the partisan has been erected: his menacing, raised right hand indicates the imperialist danger coming from the West. Four balls of time, placed at four key points, surround the monument. Uncle remembers well this time that made him the protagonist 44 years ago and resumes the narrative.

“The day of departure is coming. It was the late autumn of 1949 and two days before we had been notified: prepare your loot, the day after tomorrow you will leave for Italy. All our spoils fit into four suitcases. After many waits and postponements, the list of the last Italians to be repatriated included the names of the Pozeli and Terruzi families, who, by their own means, had to go from Tirana to the port of Durrës and from there board a ship to Brindisi .

The news so desired and so expected, came suddenly, while the family had been waiting for the authorization for four years. Amidst the happiness of leaving and crying for her husband who would remain in Vlora prison without her support, Aurelia prepared two suitcases and a cardboard box. Until that moment, the family was kept in uncertainty about repatriation, also because my grandfather and I, due to our respective professions, were needed by the regime:

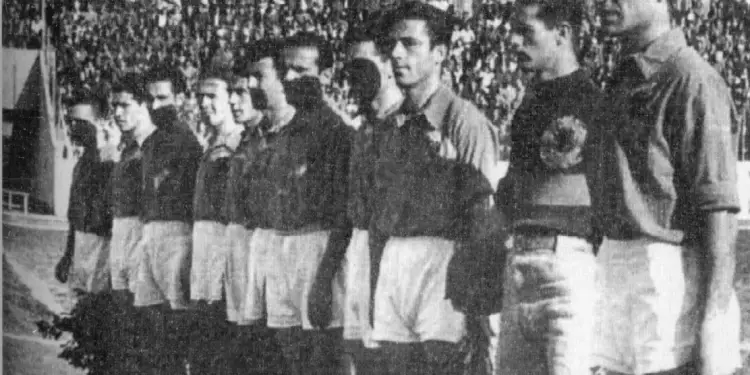

Me because I was already a famous athlete and Vitaliano because he was an expert entrepreneur. But a watchful eye also watched over Aurelia, because the Albanian hierarchs expected something from her in exchange for the release of her husband, but they never had this satisfaction. Aurelia should have started a new life, since then a double role awaited her: to become the father and mother of her son, waiting for her imprisoned husband to return to Italy.

There were six of us: me, you, your mother, my mother, my father and your great-grandmother. We believed we would board the ship the day after arrival. But it didn’t happen like that”! Memorie.al

The next issue follows