By Najada Pendavinji

– The shocking confession of Emin Xhuti from the village of Zvezdë, about the torture in the Internal Branch of Korça and his close friend who was killed in the galleries of Spaçi, the day before he was released, and what the investigator, Safet B., told him when he met him afterwards the 90s?!

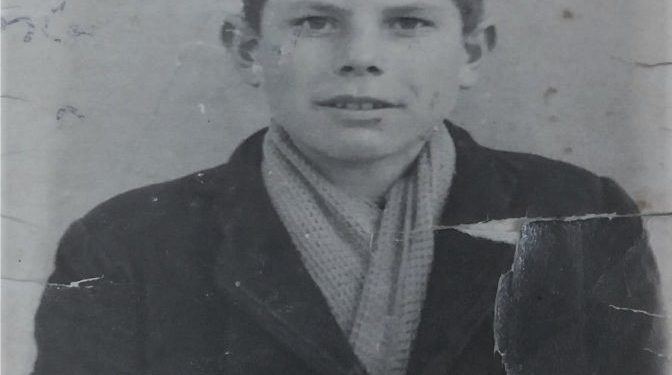

Memorie.al / Emin Xhuti were a minor when he faced the brutality of the communist regime. With smiling eyes and the hope of a child, he dreamed of leaving the dictatorship and poverty of his country, but he was sentenced to 10 years in prison. He served his sentence in the Spaçi prison camp, where he learned about the hard work in the mine and the violence of the police. The young man who did not know fatigue, was already part of a long ordeal of hardships and suffering and the best years of his life, he would spend them inside the communist hell, where he would also lose one of his closest friends, with whom he shared the dream of escape. Today, he is 69 years old and injustices have accompanied him in every step of his life.

Mr. Xhuti, what is your story?

I come from a small village in Korça, from Zvezda, from a poor family, where we all worked in a cooperative to earn a living. We lived in a closed world and hope was the only breath of freedom. We were children, but in that system we lived in, we grew up prematurely, as the communist regime was looking for victims and we would be its victims. I say this because I was only 16 years old when I faced a charge I did not commit, which was attempted escape from the state. Thought and action are two different things.

I couldn’t even make the journey to cross the border and reach my dream destination. Such was the policy of the state: it hit, persecuted, and punished each of us who, in one way or another, had opposed the communist ideology.

Although we could be “opponents”, active or passive, as in my case. Despite this, I have been sentenced to 10 years in prison for “treason against the motherland”, in the form of fleeing abroad and remaining in the attempt phase. It was a serious accusation, which would weigh on the small shoulders of a 16-year-old like me.

How did you come up with the idea of escape?

The only future that awaited us as soon as we finished school was working in the cooperative, which I had tried since I was 14 years old, since I came to my father’s place to complete the norm. Like all my peers, who believed in dreams, the almost naive hope of a child, I too thought that I could manage to leave that small village of Zvezda and Albania, but within the communist regime, the dreams of filling them was difficult yes, but in most cases, they could end in tragedy. As it happened.

We were four friends: Hariz Braho, Xhuma Shake, Demirali Karemani and I, Emin Xhuti, who every day more and more discussed how to leave Albania, especially when we went to cut wood in the mountains, where at that height, we were looking for a place to distant, so much so that even the birds envied us. The four of us had people abroad, in different destinations of course, but we were united by the idea and thought of crossing the border together.

Two of those who were, Hariz Braho, together with his brother, Resmi Braho, one 18 years old and the other 15 years old, managed to cross the border and went to Greece for almost 2 months. Unfortunately for them, the Greek state returned them and they were caught by the State Security agencies. It is understood that the consequences would be very serious for them, but also for us who had simply talked about escaping with each other. If they catch you. you had no escape from communist madness.

How do you remember the moment you were arrested?

I can tell you that I was waiting for the moment of my arrest since the very capture of Hariz Braho, with whom we had talked about escaping, led to the thought that they would not leave it at that. Plus, it turned out that we had a spy among us, which was Barie Pojani Kodra, who was supposed to help us escape, but that she was only a collaborator of the State Security structures. So it didn’t take long and on October 6, 1973 I was arrested.

During that day I was at work, picking tobacco, instead of my father. I raise my head and look at a black car, from which the policeman and the area officer got out. They called him Pirro. They approach me, telling me that we only have one clarification to make. But the policemen who put the bars on me shouted: “In the name of the people, you are under arrest.” The women who were there working fainted.

Even though I was prepared for such a thing, fear and ignorance of what would happen to me, conquered my soul, mind, and body, which made me, trembles. I didn’t want to give myself away, I summed it up by thinking: “let it be done, what’s going to happen will happen”. I had no choice…! They put me in the car and take me to the Internal Branch here in Korça.

What was the investigation like for a child your age?

The investigation (detention) has been one of the most torturous circumstances that we prisoners have experienced. I say this because it has been difficult for everyone and because of the methods used by the State Security during the investigation. Interrogation, torture, beatings, ill-treatment, humiliation. So in the conditions of isolation and constant violence, so much so that sometimes we were surprised if the investigator behaved “inhumanely”.

For a person of the same age as me, all these were the bitter unknown which would accompany me for a year as an intense investigator. The investigator of my case was Safet Bala, a short man, stern in manner, handsome, always waiting with sawdust in his hand, to interrogate you.

I did not accept any charges, as I never tried to escape, I only thought about it. I met Safet Bala years after I got out of prison, even though he denied that he was my interrogator, I remember very well his frowning face and his hands hitting me. Isolation for a year in the dungeons of the investigation became unbearable, so punishment seemed necessary to me.

How did the trial go?

The trial took place on March 20, 1974, in the Court of Korça, with open doors. Also present were my parents, mother and father who seemed to be very overwhelmed by what happened. In this trial, all four of us who had talked about the escape appeared. The prosecutor of the case was Femi Molla.

Barie Pojani Kodra, whom I mentioned, was a witness. Pretence decided the punishment for the four: Ariz Braho was sentenced to 14 years in prison; Juma Shake, 15 years in prison; I, Emin Xhuti, with 10 years in prison and Demirali Karamani, with 8 years in prison. The same charge: “for attempted escape”. The communist trial has always been a “comedy” with tragic endings.

After they sentenced you, where did they take you?

Immediately after the end of the trial, we are taken to the shacks, which were transit rooms for the prisoners who would be transferred to the communist camps and prisons, which were many in number.

There, you were waiting for where you would spend your days, nights, months, and years of punishment. From there, they took the four of us and took us to the Torovica camp in Lezhë, where most of the prisoners were regulars.

But they needed work; we stayed there for almost three years in Torovica. The atmosphere that prevailed in this camp was suffocating, due to the very fact that the mixture of political prisoners that we were, with ordinary ones, hindered the relationship between the convicts.

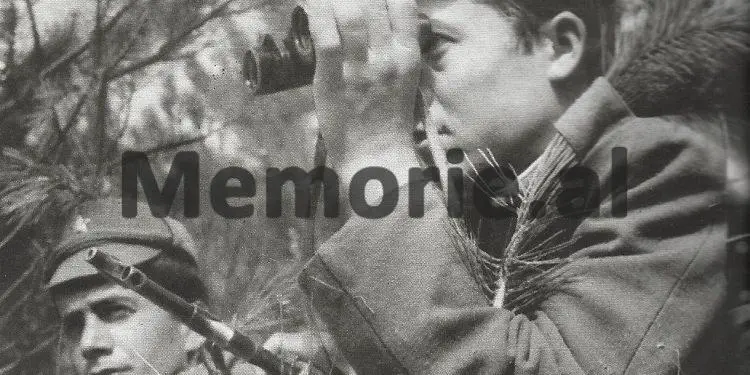

After three years, in 1977, I was transferred to Spaçi camp. I didn’t know what it was to work in the mine, in the gallery, working three shifts to make ends meet. Spaçi gave him this “opportunity”, where he experienced not only the hard work, but also the violence of the policemen, for one of the most unusual reasons.

The extreme violence that occurred in this camp was accompanied in most cases by victims among the convicts. Pjeter Koka, was a captain in Spaç, the meanest policeman, who would move your head, beat you and not only: punish you by putting you in the dungeon.

The same thing happened to me, I was put in the dungeon for almost 30 days after they found a clipper, a small knife under the mattress, that I used to cut my nails. The dungeon was terrible, it was icy, the snow was coming in, the body clothes were thin, and we only had two blankets: one down, one up.

Here in the dungeon I found Fatos Lubonja. An intellectual man with whom you wanted to talk and spend time, forgetting where you were.

Although it was difficult to be friends with everyone, you couldn’t trust everyone, time and the prison we were in imposed communication and a close relationship with some of the convicts. As was the friendship with: Nevruz Golka, Úngjëll Fidanin, Dhimitraq Zguron, Mina Kota, who worked as an engineer in the mine.

Have there been accidents at work?

Working in the mine was excruciating. Even though it was in the form of exploitation, we there earned something to support ourselves and most importantly not to fall on the necks of our family members. I worked as a wagoner.

The difficulty of this work consisted not only in the effort it gave, but because it was done with force and coercion, otherwise the wood would crack. There were a lot of accidents, where in most cases, they ended fatally. I escaped “peacefully” as we can say, since the wagon cut my finger just a little bit, on the job.

But I remember that during the work in the mine, where we were all prisoners, a small part of the tunnel collapsed and only one of us got inside. Terrible were the screams and cries of that man, who died under the ruins, leaving them there forever.

There have been other cases where these accidents were planned and instigated by the prison command itself, in order to carry out the next executions. That’s what happened to my friend, Hariz Braho, who was killed when he was released and released.

He was a wagon driver; during his shift they threw the wagon over him, leaving him dead on the spot. This happened after I was released and I went together with his brother to take the body.

It was really tragic because the family was waiting for his release. But no one could imagine the methods used by this regime for the purges against the “enemy element”, which it did not consider as human beings at all…

Did your family come to see you in prison?

Communication with the family was necessary, since in the situation we were in, we needed some strength, moral and spiritual support, which could only be provided by contact with our mother, father and other relatives. I have only had two meetings with my parents, one in the Torovica camp and one in Spač.

This is because of their distance and age. They could not bear to see me in that state. The meetings had no possibility of privacy as they were held in the presence of police officers. It was difficult, but it is enough to look at them and deal with them. We had nothing to do. This was the life of the communist prison.

How do you remember the release and what happened to you afterwards?

It was November 1982, where I listened in the TV room to Enver Hoxha’s speech about amnesties and reductions in prison sentences. It seemed so propagandistic that I was not at all impressed by the remission of the sentence, compared to what I had experienced during that time.

After that, the camp commander comes with a list in his hand, lining us up exactly like a flock and reads the names of those who were pardoned: my name was among them. I meet my friends and get in the car, which stopped in Korça.

It was getting dark, it was cold, I was thinly dressed, I had to walk to go to my hometown, Zvezda. I arrived late and when I knocked on the door of the house, the first mother came out, who fainted when she saw me. I stayed with them only that night, because in the morning the village courier comes and informs me that I have been named a soldier.

I couldn’t deal with them. After I finished the army, I came back and now I had to find a job to survive. Through many struggles, I managed to find a job in Erseka, where I can say with full conviction that here I felt every day more and more that “damka” as “enemy of the people”…! The unlucky, unlucky, stays for the rest of his life…! Memorie.al