By Najada Pendavinji

Memorie.al / He was only 17 years old when he decided to escape, but his friends spied on him and he ended up in prison, experiencing the most terrible tortures. But he would receive the strongest blow at the trial, where the investigators recorded his father’s voice saying: “He is no longer my son, if he has gone against the communist system.” This is the story of Nevruz Golka from Korça, who spent the best 20 years of her life in Spaç and had no home to return to when she got out of the communist prison.

Nevruz Golka is one of those persecuted by the communist regime of Enver Hoxha and his successor, Ramiz Alia, for whom the ordeal of suffering began at the age of 17. For Golka, the Albania of the communist dictatorship was not a country that could provide him with a future, since he was a child with a parent who was a political convict, from the beginning of the communist system and the breakdown of relations with the Soviet Union in 1961 cut off all paths for young Albanians to study abroad.

Thus, the only way to leave communist Albania was to escape through the border. But this initiative is interrupted in the middle, experiencing the communist revenge, which was merciless. The ordeal of his suffering and persecution begins on the very day of his arrest, November 15, 1963, and ends after 20 years, in November 1983. Nevruz Golka served his sentence in Spaçi prison, who also became one of the witness’s spectacles of the May 1973 revolt.

Golka testifies to the determination of the prisoners for freedom and how this revolt shook the communist regime to its foundations, causing panic among the top communist leadership in Tirana. His greatest trial is when he is released and must return to his father, with whom he had no correspondence during the entire time he was in prison, aware that he would not be accepted by him. Today, he is 78 years old, an activist and volunteer in the protection of the rights of former Persecuted and Political Prisoners in the city of Korça.

Mr. Golka, what is the origin of your persecution?

The story of my persecution begins at the age of 17. Even though I had a form of social differentiation from before, since my father was sentenced to prison at the beginning of the communist system, on the charge of “making a coup d’état, subverting the people’s democracy”. But the moment of escape was decisive for my persecution.

In 1961, when relations with the Soviet Union were broken, among other things, the path of students to study abroad was also interrupted. So we decided to leave communist Albania in a different way. We were a group of like-minded students who decided to escape across the border.

Of the seven people who were together, to leave, all seven of us left, while to be arrested; only three were arrested, since the other four had notified the Department of Internal Affairs earlier. This was a fair proportion of that time, as the State Security worked hard to protect the state from the elements that organized crimes against it.

As a result of being spied on by our friends, our initiative to escape from communist Albania remained at the tentative stage. I was arrested on November 15, 1963, in the late hours of the night, in the soft zone of the border, taking photos of the traces to be called flagrante, in order not to have the possibility of deviating from the investigation.

What was the investigation like for a teenager your age?

The arrest was made by the head of the Security of the area, Sotir Ndrio, who used merciless violence against us, torture and beatings never experienced before. Even today, I can still have scars on my body from the shoes with nails, which shot us in the face. During those tortures, we fainted; they threw water on us to wake us up, continuing the violence.

Until they took us to the interrogator, that violence was terrible, and when we entered the dungeon, we called the walls a shield, as we thought that we were thankful that we were saved from being beaten, from being tied up, from being kicked by the Chief of Security of the area. The dungeons of Korça were terrible, with no windows, no ventilation, only that they gave us a blanket at dinner and took them away in the morning.

During the night, it was very cold and we slept on our feet, walking through the dungeon, and it is surprising that we never bumped into the wall or the door of the dungeon, as we knew very well where the place was. In the morning, we were woken up by the kettle of food coming from above and the heavy shoes of the policeman. But we didn’t know that the investigation would be so intense because they thought that we were related to a saboteur who, at that time, entered and exited Albania with the last name Kulina, was a shepherd.

So the investigation was very tough and intense, thinking that we were getting information from this saboteur and he had instructed us to cross the border and turn into agents, according to the investigator’s mind. For this reason, the investigator began nine months, and at our age, it was terrible, since we were on the threshold that we could cross into madness, it was something unknown to us.

Various questions were asked there, various provocations. At 12 o’clock, the investigation began and until 6 o’clock, the chairs were made of iron concrete. I was tied to the chair and the investigator even pretended to sleep and left the cobra on the table, waiting for my reaction, to provoke me. The investigator who had my case was called Riza Shehu from Berat, but he had come here on duty in Korça.

Can you give me a description of the behavior of your police officers or investigators?

Policemen and investigators were the most loyal people of the party and the state. They were their chosen ones to commit crimes against the enemy element, not even sparing the children. But I can say with full conviction that, at the same time, the police were also the most ignorant people in that structure. They looked as if they had studied them and determined that this man only does this job; they must be bloodthirsty and cold-blooded.

I remember that when we were in the gallery of the Spaci camp, one of the prisoners asked the camp policeman and said: “You are anti-imperialist”? “Yes” he answers. “You are anti-revisionist”, he is answering. “You are anti-communist”, he is answering. So with these words, it is implied that they had no idea what position they had and what they had to protect, but one thing they knew for sure was to use violence and torture against anyone who was put in prison.

How did the trial go?

After the end of the investigation, the trial took place. The trial became exemplary. It was carried out in the village school, to show our peers what awaited them if they acted like us. The chairman of the court was Ibrahim Zhuli, who was very strict. The whole village had gathered there, and those who loved us were very sad, while others insulted us. We still didn’t know that our friends spied on us, as we thought they were in the investigation with us.

But when they appeared in court and gave their testimony, then we realized that they had betrayed us. They tried to put the biggest blame on me, describing me as the leader of the group, and when we were punished, I was punished more, because according to them, I insisted more on leaving. But I really was more eager for a better life and hastened my escape, as they had been talking about it for a year, but I did not stop.

But apart from that, a very difficult moment for me was when I heard my father’s voice recorded in this trial. He said: “He is no longer my son and give him the punishment he deserves, even by firing squad.” I don’t know if he said it from his heart or forced it, but I know for sure that he was the voice of my heart.

How many years in prison were you sentenced to and where did you serve your sentence?

After the end of the trial, which was a great victory, a liberation, as the prison was a collective life and we were allowed to meet with family members. First, they took me to the Korça prison, then, in April, they came and took us to the auto-prison and took us to the Laçi camp, as they needed labor to build the Superphosphate Plant.

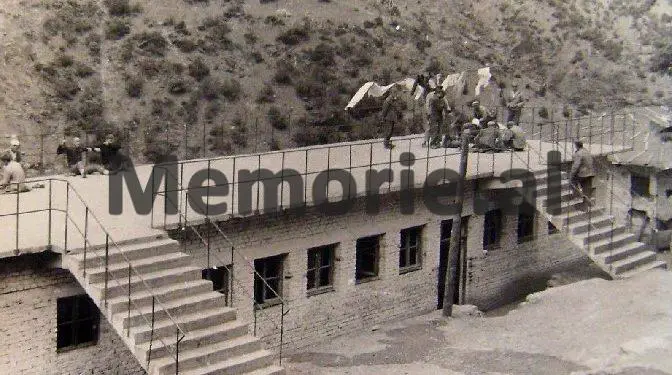

We stayed for three years and after that, they took us to Elbasan, as the Cement Factory was going to be built, where I stayed for a year. And I served the sentence of 20 years in prison in Spaçi prison camp. Thus, the cars covered with plasmas came and transferred us to the Spaçi mine. I remember that we left in the morning and barely arrived late at night, and one of our friends on the way said: “Yes, Albania is very big”.

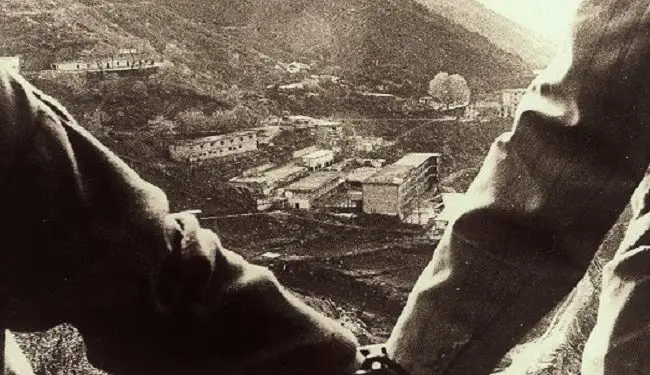

When we got there, Spaçi was terrifying. It was a valley between two rocks, in the winter it was terribly cold, in summer when that stone was heated, you could not stand, it was very hot. We stayed in huts made of populi, which were the dividing walls of the silo. Through them, snakes and lizards entered, and there were also countless scorpions and lizards.

Here, we also saw “lice with tails”, so the hygiene of the place was terrible. Working in the mine was exhausting for my age; you had to do the norm. There were times when we stayed four days in the gallery, to complete the norm. We stayed there without bread, and when the next shift came, he could share the food with us. I remember a case in the gallery; something happened that we couldn’t achieve the norm.

I was together with one of Dibra, when the policeman took us and raped us by tying our hands with irons, he squeezed us hard, until we fainted, and he woke us up and started squeezing us again. In Spaç, life among fellow sufferers was relatively good, the children supported us. There were educated people there and we learned from them.

I remember that there was Gjergj Komnino, a Gyrocastrian, well versed in foreign languages, which carried a book “Italian Encyclopedia” and read it in the prison yard, while we watched him as he browsed. He allowed us, but because there were many of us, he told us; “Please, don’t block my sun, don’t stop me from what God gives me.” At this moment, something really strange happened.

In prison, Mehmet Shehu comes to our airtime. He was truly an irresponsible man. Those who knew him, stood up and were surprised, since he was alone, and approached Gjergj Kominos, calling him; – “Professor”! He raised his head and said; – “After the prime minister came. Why are you tired”? Mehmet Shehu says; – “I want to ask you a question, explain the class struggle to me”?

And Komino explains: “You took a bottle and put vinegar and oil in it, and necessarily the oil will stay on top, while the vinegar is on the bottom, these are the laws of nature. You always keep that bottle shaken, so that the oil is mixed with the vinegar and you cannot tell who the oil is and who is the vinegar, that is, who the wise man is and who is the criminal.

Aman, don’t forget that if you don’t shake that bottle for just a moment, the oil will always stay up.” Mehmet Shehu was very revolted by this answer, insulting him in the most vulgar way.

How do you remember the three days of the Spaci revolt?

I was an active participant in the Spaç revolt. And I can say with full conviction that this revolt shook the communist regime from its foundations, spreading panic among the communist leaders of Tirana. The revolt, of course, had a spark, which caught fire for three days in a row. The first day started as a normal day.

It was May 21, 1973, when we prisoners realized that we had to make some demands to improve the living conditions in the camp. We presented these requests to Sulejman Manoku, who was the General Commander of the Prisons of Albania. These requests had to do with the water, which was acidic, having a rust color, with our removal from work in the mines, amnesty, etc., but of course these were not taken into account.

There was a fight between the prisoners and the prison guards, where we managed to get our comrades out of the isolation rooms, causing the crowd of prisoners to increase even more. In all the premises of the prison, you find prisoners gathered who also gave speeches and recited poems with content against the popular power.

Like Skënder Daja, who was also shot, who gave a speech where he said: “Down with Communism”, “Long live Free Albania”, “Here is death, here is freedom”, or even Dervish Bejko, etc…! As a result of this, they began to take strict measures, notifying not only the Department of Internal Affairs of the Mirdita district, but also the Ministry.

So Feçor Shehu himself came, who brought reinforcements and declared that: within 5 minutes, everyone was liquidated without exception and that the revenge would be merciless.

But we didn’t stop. On the third floor of the building of the leaders of the command, the prisoners had raised an Albanian flag with two proud eagles without the communist star. The flag was improvised, taking the red piece of Naim Pasha’s quilt, while the painter, Mersin Vlashi, painted the eagle without a star.

As the flag was being hoisted over the building, the soldiers started firing in volleys and surprisingly, the flag was not hit by any bullets. The suppression of the revolt, as they also communicated to us, was done violently. Constantly, around the camp, sounds of cars, maneuvering of tanks, armament, loading and firing of weapons, etc. could be heard.

Those who dealt with the issue of the revolt, I remember, were: Aranit Çela, President of the Supreme Court, Kasëm Kaçi, Chief of Police of the Republic, Dhori Panariti, Prosecutor General, etc. Of course, the revenge after the suppression of the revolt would be merciless; the punishments would be up to shooting. Fighting with them was terrible.

Those of us who objected were beaten with the tail of a shovel. I remember that, they even tied us with chains, putting us all in a line. The chain went from the feet to the hands, from the hands to the neck and to the mouth; they put locks on us and threw the keys into a big cauldron.

Did your family come to see you in prison?

All prisoners had the right to visit their families. The only family member who met me in prison was my grandmother. I remember that he came to Korca prison and brought me change and food.

But before he met me, he asked the Prison Commander and told him: “I have raised my grandson since he was very small and I know that he has not done anything harmful to be in prison.”

The commander tells him: “When you meet him, tell him that if he agrees to do what we tell him, his sentence will be reduced.” And she, so happy, comes to me and tells me that; it was up to you whether you would be released or not.

And I tell him, but I know what they want from me, they want me to become a spy. No, she says; don’t come home to me, if you will. That was the meeting with my grandmother and I never saw her again, because she got sick and then passed away. As for my father, I never had a meeting.

What happened to you after you were released?

My sentence ended in February 1983, but due to an amnesty, I was released in November 1982. For me, this amnesty had no value, as I only had 1 month and 20 days left to be released.

I was 38 years old when I was released. I had to go back home, where no one was waiting for me. I went to the village and aware that my father would not accept me, I send a little boy to the house to inform him.

But his words were the same as those he had expressed in court. So I headed to the Home Branch, explaining my problem. Its officials accommodated me in the guard officer’s office, which was a very small space, where there was not even a bed to sleep on.

I stayed there for almost 4 months. Then, they took me to the mine of Mborje-Drenova, where I stayed in the hotel that was for bachelors and continued my life, of course with the stain of the biography, until the system changed. /Memorie.al