By Sami Repishti

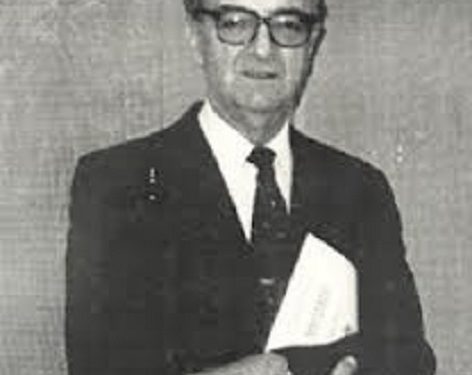

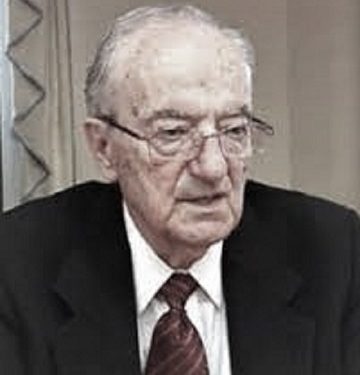

Memorie.al / Sami Repishti were born in the city of Shkodra in 1924, in a family with patriotic traditions. His grandfather was a fighter of the Albanian League of Prizren in 1878, while his father fought against the invading Serbian-Montenegro intentions. After finishing high school in his native country, he earned a right to study in Italy, where he graduated from the University of Florence, in the Faculty of Modern History. In 1945, he was arrested by the State Security and sentenced to 15 years in political prison, accused of “agitation and propaganda against the popular power”, of which he suffered 10 years, mainly in the camp of Beden i Kavaja, Vločisht and the marsh of Maliqis. After being released from prison, after working for some time as a laborer and carpenter in a construction company, on August 22, 1959, he escaped from Albania and went to Yugoslavia, where he obtained political asylum status for the USA. In 1977, in France, he received the title of Doctor of Science in Philosophy. Sami Repishti, is among the first Albanians in America, who in 1965, before the American Congress, demanded that Kosovo be granted independence. In 1968, he formed the organization “Kosovo Albanian Youth, in the Free World”. In November 1982, together with Arshi Pipa, they organized the International Conference on Kosovo, with the participation of 14 European and American professors, also making a petition to one of the officials of the European Parliament, Otto von Habsburg. In 1978, he got involved and created the company “Kosova Relief Fund, USA, Inc.”, for financial assistance to persecuted families in Kosovo, which foundation he remained at the head of until 2000. For more than ten years, he has held the column on Kosovo for the newspaper “Dielli”. In 1986, he requested the opening of the American Office in Pristina, which was successfully completed in 1996, and the Kosovar one in Washington, which was approved by the 46th President of the USA, Mr. William Jefferson Clinton (1993). Repishti is also co-founder of the Albanian-American Civic League (1986) and executive director (1989-1992), co-founder of American Friends of Albania and its secretary/treasurer (1992-1996), co-founder of the Albanian-American National Council (NAAC 1996 ) and first president (1996-1998) – the most influential lobbying group in Washington D.C. Currently, he continues to deal with Albanian studies and the protection of Human Rights. He is also engaged in various studies, publishing books and writings. The writing that we have selected for publication is taken from his memoirs and talks about the period when he was serving his sentence as a political prisoner, in Bede i Kavaja, in the drying up of the marsh.

A FRIEND AND A TEACHER

At the beginning of June 1948, in the marshes of Beden i Kavaja, the caravan of prisoners was unloaded. On a hillside, a row of large shacks covered with old tins and surrounded by mats, were designated for their residence. On all four sides, four-meter-high barbed wire surrounded an area of about a quarter of a hectare.

In the corners of the guard tower, where soldiers were equipped with machine guns, carefully followed every movement and stopped under the threat of death to approach the fence. More than 900 unfortunate people were inside. It was the camp, which later became known as the ill-fated Beden camp.

They had organized us into brigades and companies. And some scum of the society ordered us. We bowed our backs early in the morning and in the mud with insects and snakes, we sank under the lash of the sticks, which the hand of the police played mercilessly.

We worked non-stop, our heads hung down, our clothes drenched in sweat, our bodies were dry from suffering and our arms and legs were torn from hard work, we could hardly manage those rhythmic, monotonous movements that we took out the soil and mud, in a quantity that we were told was “norm”.

In the evening, in the camp, we would line up to bless the bread, and without much exchange of words or conversation with our friends, exhausted from fatigue, we would lie down unwashed, unwashed, in old curls, which we only called our beds.

* * *

As every day we are lined up for work. It’s dawn. When the light opens and takes the soil, we leave. A caravan without line, without form. Surrounded by guards with wood, we pushed with the last runaway that does us without mercy. We can’t get close to the first thing that makes us hurry. The sides are not allowed to rest; they get up, bear countless sticks on their backs, and go on the road again. A sight that still twists my body!

A friend fell one day. Be by my side. Before I could help him sit down, a strong hand almost lifted him. Then I helped him too. We were returning to camp and together with the weight of the day’s fatigue, we both carried to the place a body that seemed to have the last hours. We didn’t speak the whole way. In front of the barracks, we dropped the sick on the ground. It didn’t move.

We call the nurse, who luckily for us is really a hero. He carefully picks it up and puts it on the bed. From the look on his face, we understood everything. Sitting on the head of the one who was giving his soul, we exchanged the first two words with the one who had helped the sick with me. From that day I started dating my friend.

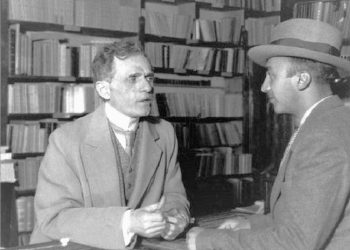

We found the occasion when we were going back and forth for work in groups; he greeted and talked to me. In the camp it was more dangerous. One day, after I told him my name, he told me his name was Hamdi Gjoni. He majored in religious studies at the Madrasah of Tirana and had a rifle since his youth and served wherever duty called him. He had a masculine appearance.

A strong body that never got tired. A fizzy lip, with such ease that you could tell it was his nature. He spoke slowly and with conviction about everything he uttered. I liked him from the beginning and when we got to know each other properly, I started to love him. In the hard hours of work, in the endless days of suffering in the camp, we came close. He was my elder, he advised me. It was more practical, it helped me.

And in his stoic, courageous and unyielding attitude, I began to see an example that everyday life did not often give me. A figure that attracted me, that made me his own, that I loved and inspired me with self-confidence and determination. In the middle of a sea of misery, he became for me an island of support and support. I was happy, I had found a friend.

* * *

During the work, not far from us, the policemen and their servants were trying, mockingly, to put a wheelbarrow full of soil on the back of a man about 40 years old. It was an everyday sight. The sick, the old, the weak, were beaten and tortured every day.

They were required to work, a lot of work, and when the strength was completely exhausted, then the torture began. The man who was struggling to stand under the heavy weight of the earth was dry and weak in body. It wasn’t long. A pair of thin legs, trembling with weakness, had to support the weight of a skeleton whose hip bones were counted.

After a while, he fell to the ground. Then began the kicks of those who called us the commander and the batons of the policemen with uniforms. More than one gave up the soul on the spot in these cases.

– “Bastards”! I heard Hamdi’s fairy near me. I looked at him with wonder! One such word could cost a life.

– “I have a friend” – he told me. We didn’t talk for a long time. An officer was watching us from above. We lowered our heads and the movements of the shovel followed each other. He explained to me when we returned to the camp: “He is from my country, – he told me, – “he was a professor and one of the first fighters. It is very good and I love it very much. I will introduce you to him. They call him Bego Gjonzeneli”.

I met the professor many times after that day. After the first usual words about the life we were going through, it was the new situation we created that gave us dough for conversation. A few days after the Informburo resolution of June 1948, we were forced to listen to the reading of the newspaper. Rijshim sits in the camp yard in a scorching sun and listens to the reading of the newspaper.

Rijshim sits in the camp yard in a scorching sun and listens to hour-long readings of our hypocritical speeches that are held all over the country. But we had another concern, would this situation that seemed to be shaking at the bottom last even longer? No one knew for sure.

We were hermetically isolated and any attempt to make contact with the outside world was impossible. I was still young. Listen carefully to the words and thoughts of others. But you wanted the conversation with the professor more. I still have it in mind. He lay on the dry ground, leaning on his right elbow.

Always with two or three others. He thought constantly. It was as if he wanted to tell me what he thought. He spoke slowly, very fluently and with a connection of thoughts that he kept to himself. He was worried about the fate of the country and ours. We escaped death in Beden. A few months later we met in the marshes of Maliq. We hugged like old friends.

* * *

They took us from our midst, without knowing it, one day in September. I couldn’t even greet him. Hamdiu told me that he and four others were returning to Vlora prison. I didn’t understand.

“You will find out later,” he said. – Goodbye, maybe, forever”!

I was stunned. I only saw how, with their hands tied, five comrades were getting into a truck, hidden by armed military guards.

At the end of March is the anniversary of that massacre that I found out about two months later. I was told that seven had been executed, for an attempt to escape from prison. Professor and Hamdiu were among the first. The news came to me suddenly and the effect nailed me to the spot. I was frozen in my legs without knowing what they said to me.

I wouldn’t see them anymore and their fairy tale wouldn’t sound anymore in the circle of our society. I glanced at my friends from Vlonia, who usually stayed with him. They were prey. He lowered his head; it seems that they still had not recovered from the heavy loss. I then tried to find out about their last days. They told me that they despised the mercy we offered.

I believed it. I had heard with my ears the wave of their hatred every time the word was spoken. I felt proud of their determination. As if it inspired me with conviction in the justice of my ideal.

And when in my heart I struggle with difficulty, I am convinced that they are dead, they do not live anymore, they will not live anymore in our circle, a feeling of pain as if it tightens my chest, squeezes my heart, and on my face, the sun and the wind , two teardrops roll involuntarily.

All day I live spiritually with them. Memorie.al