By Hajro Hajra

Second part

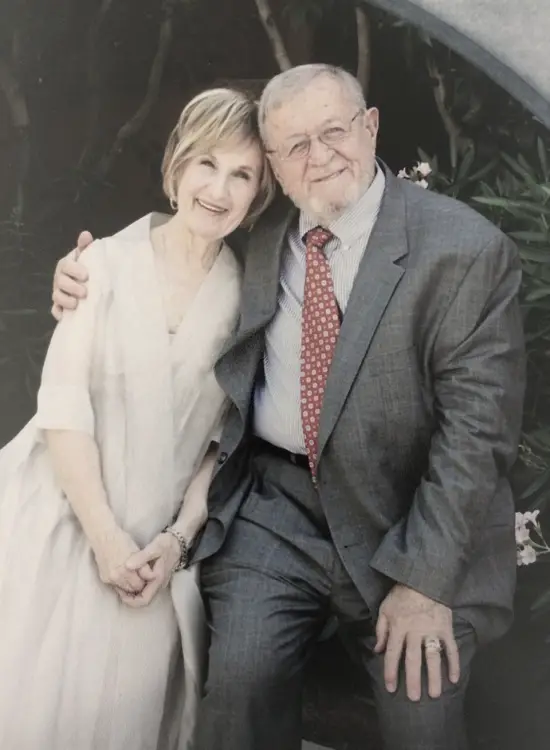

Memorie.al / An authentic narrative, lived and unadorned, drawn from the carved, but not sleeping, memory of the Albanian who experienced the communist hell, but who managed to escape from that hell thanks to the resourcefulness and great faith that only by coming out of that purgatory, you can fight that icy winter, that infernal fog that had covered Albania from corner to corner, you will read in this article about Remzi Barolli, sentenced to 101 years in prison by the communist regime of Enver Hoxha.

Continues from last issue

Punishment for saboteurs

The communist regime was closely following the behavior and actions of the internees. However, even under the conditions of an iron siege and a strict surveillance, the internees found a way to act. Before the completion of the Durrës-Elbasan railway, the Peqin-Elbasan segment, on May 3, 1950, a very large number of internees were arrested, a total of 3,000 people, accused of sabotage. Among them was Remzi Barolli.

When we ask him about the reason for the arrest of such a large number of people, Mr. Barolli says: – The Albanian government at that time helped the Greek communists in all possible ways. Among other things, he helped them with the transport of military equipment on the Durrës-Elbasan-Pogradec route.

We, the internees, did not see this action of the Albanian authorities with good eyes, therefore, unable to undertake anything, we emptied the mortar against the Greeks, as well as against ours, damaging the Greek vehicles (deflating their tires, he broke windows and wooden parts, throwing gravel at engines, etc.) The police had caught one of us, and then that number had reached a staggering number – three thousand.

From the first day of their arrest until the end of August, the detainees were strangled until they were forced to admit what they had done and what they had not done. In September, the trial at the Military Court of Korça began. It was a judicial farce that was done “in the name of the people”, to punish the people.

Several hundred people were tried in one day. Three hundred accused from Korça and Pogradec were tried in three days. The arrested were brought to the courtroom in chains. In addition to having their hands and feet chained, the prisoners were also chained to each other, making it difficult for them to move and stand up.

For Remzi Barollin – life sentence

The first 11 accused were sentenced. They were the heaviest sentences handed down in that farce of a trial. These 11 accused, of which Barolli remembers three names, one, young in age, was called Llambi and had been in the same cell with Remzi Barolli for two months, another elderly man was called Zaim and the third was called Latif, were sentenced to death and were shot. Remzi Barolli was sentenced to life imprisonment. Together with Remziu, there were two other Barollins, brother and sister, Nejdeti and Fitneti, who were sentenced to 35 and 25 years of imprisonment, respectively.

Remzi Barolli experienced the pronouncement of the sentence of 101 years, or life imprisonment, very hard. He was a twenty-year-old boy, the best age of man, and he would spend his whole life in prison or in labor camps, or as they called them, “Socialist re-education camps”. This was terrifying for Remzi. Deeply depressed, in moments of fainting, at first he had no other thought but how to end his life. It was one of the worst moments of his life. He felt alone, without anyone in the world.

After they had pronounced the sentences, the prisoners were distributed, depending on the sentences, in different prisons or (mostly) in labor camps. The prisoners were of different ages and professions. There were also intellectuals, but most of them served their sentences in the notorious Burrell prison. In addition to Albanians, there were also some foreigners (Germans, Italians and others).

The prisoners worked all day and the jobs they did were the hardest and most dangerous. They built factories, apartments, opened tunnels. Remziu had worked in the construction of the Oil Refinery in Cërrik, in the construction of the Brick Factory in Korçë, in the opening of several tunnels and others.

– I did the prison in Korça, in Tepelena, in Pogradec and in Saranda, – says Barolli. – Saranda was the most terrible prison. It was a prison. It has been very cold. There were many mice. The rats also ate our bread, that bread with which we were never satisfied. I saw with my own eyes when a mouse ate a prisoner’s ear.

The despair that had gripped Remziu in the beginning was slowly being replaced by a thread of hope that, however, maybe another way could be found. It was the idea of escaping, which had occurred to him at the height of despair that had raised his hopes. It was an idea that seemed impossible to realize, but it was better to process that idea than to deprive him of life.

Escape plan

Prisoners were often moved from one prison to another or from one labor camp to another. At the beginning of 1953, Remzi Barolli was moved to Pogradec prison. A cousin of Remziu, the son of his aunt, Haki Tare, who had the rank of major, was also serving his sentence there. Major Hakiu had made the escape plan, together with another prisoner, the German Major Frederik Fritz Schmid, who was also a mathematics teacher and taught mathematics to the prisoners.

This plan was quite difficult to implement and required time, but the two majors, one Albanian and the other German, after having elaborated it in detail and, of course, in the greatest secrecy, decided to implement it. Regarding this plan, Remziu confesses:

– It was a beautiful spring day, when my cousin Hakiu approached me and told me about the escape plan. He asked me if I wanted to leave. He told me: – You accepted, well, if you didn’t accept, bury these words. I, of course, agreed. I had worked out the plan to escape in my head for a long time and I wanted to use the opportunity that was being given to me. Even my cousin, Major Hakiu, encouraged me, saying: – You are young. Just like that, you have everyone in jail. If you run away, you won’t endanger anyone. Major Hakiu himself would not escape, because outside the prison he had his mother, wife and two children, who would experience double hell if he escaped.

According to the plan, eight people would escape, two of whom were the German Major Shmid and Remzi Barolli. After they had agreed on every detail, that group of eight people, together with Major Hakiu, who would help them until the end, had set the date of the escape: November 29 was the most suitable day.

Escape from prison

November 29 was chosen as the most suitable day to escape, for the simple reason that the prison staff would celebrate the November holidays, but the prisoners would “celebrate” as well. It would be celebrated with food and drink, a joke would be created, and suitable circumstances would be created to escape without being noticed. Remzi Barolli and his friends, who were going to flee, were eagerly waiting for the day when the escape plan would begin to be implemented.

On the day set for the start of the work on the opening of the underground tunnel, the prisoners had provided some tools (shovels, pickaxes, pickaxes, hoes), had made a wooden ladder and were waiting for the favorable moment to go to the latrines, which were in the yard of the prison, from where they would start digging the underground tunnel. The whole thing was being done in extremely great secrecy. It would be enough for the slightest carelessness, a mistake whatever, and, besides the whole plan prepared for months failing, the prisoners who tried to escape could be put to death, without a trial at all.

At the appointed time, out of the eight prisoners, three people go to the latrines, lift the lower boards of the latrines and, with the ladder, descend into its hole with the tools. From there, the digging of the tunnel would begin. First, they dig an underground warehouse, to leave the tools and the ladder, and then, they start to open the long tunnel. They worked every day, mostly at night and were constantly on guard. The works went slowly, because the work, apart from being heavy, was also dangerous. The excavated soil had to be taken out and thrown across the large prison yard and disguised so as not to be noticed.

There were moments when they merged into a feeling of fear, enthusiasm, will, desire, Remzi Barolli remembers today and continue:

– Bleeding to escape from that prison-hell made us strong. We were all young (the oldest was a German major, 30 years old) and, although more hungry than full, we did not lack strength. We worked without a set schedule. We were released into the tunnel whenever the circumstances allowed us, whenever we were sure that no one would see us.

– Fortunately for us, things were going exactly as we had planned. The underground tunnel was getting longer and longer. The night of November 28-29, 1953, found us with the finished tunnel, which was several hundred meters long, – Remzi Barolli continues to narrate. – Those holidays really made a mess even in the prison. The guards and the entire staff of the prison seemed carefree, songs were heard, and gunshots were heard. The night of the 28th at dawn on the 29th of November had been very suitable for escape. It was a dark, hellish night, with a downpour of rain accompanied by thunder and lightning.

The eight prisoners had also set the time of their escape: one hour after midnight. The only person who wished them luck that night was Major Haki Tare, who himself remained to serve his sentence (he stayed in prison for 41 years and was released in 1991).

After making sure that no one would notice them, the prisoners had gone to the latrine, removed the planks enough to fit into the pit, and, one by one, had slipped down into the tunnel, which led away from the yard. of prison, somewhere by a river. Remziu had been the third in a row. Step by step, they were nearing the end of the tunnel. They had agreed that at the exit the first one would wait for the second, the second the third and so on, until they all reached the exit, so that they could make the next journey together, due to the unknown terrain.

However, on the way out, a small carelessness of one of the fugitives (perhaps the cause of unrestrained joy), and the fugitives were dictated. The projectors were on, the shooting had begun. One of the escapees had been wounded by the guard, while two others had fallen into their hands. The other five, including Remzi Barolli, had managed to escape, although the police and the army were behind them and had chased them, but the night had been so dark that the fugitives could barely see each other. It had been a cold night.

It was raining incessantly. The rain hadn’t stopped throughout the night, which luckily helped them to leave no traces. The clothes were too thin. On their feet they were wearing sandals. It was necessary to walk through difficult terrain. The level of the river, which they had to cross, had risen due to the heavy rain that did not stop for hours. Although icy cold, the fugitives had managed to swim across the river.

Although the danger had not passed, the five escapees were feeling relieved. They had left behind that hell called prison and away from there, even if they were killed, their lives would not suffer. The fugitives made the long, dangerous road to the Albanian-Yugoslav border, somewhere between Dibra and Struga, only at night. During the day, they hid in a safe place and as soon as night fell, they continued on their way. In the first days of December, they managed to cross the border and took shelter in the house of an Albanian, in a village in Struga (unfortunately, Mr. Barolli did not remember either the host’s name or the name of the village).

The owner of the house had sheltered the unknown fugitives, but he had not left them without reprimanding them, because they had left one prison to come to another prison, called Yugoslavia. The five fugitives had stayed in that house for a week. The owner of the house, despite the risk that the Serbian-Macedonian police could discover him and arrest him together with the guests he was hosting in his house, had welcomed them very well and had helped them to cross the border to Greece.

In Greece

On the eve of Kërşendella in 1953, Remzi Barolli, together with the German major and three other Albanians, after many vicissitudes, after many dangers that they had encountered during the journey that they made only at night (of course with the help of Albanians from the districts of Struga and Ohrid , who did not want to know about the danger), had managed to cross the border and enter Greece.

Although they would face various troubles in Greece (because they had broken the law by crossing the border illegally), for the first time after those years spent in Albanian prisons, they were feeling free. For the four Albanian fugitives, it was a mitigating circumstance that the German major was with them, who would help his fellow prisoners to pass more easily to the Greek police authorities during the extremely long verification procedure and during numerous formalities.

The Albanians were young, did not know any foreign language, for them it was the first time they were outside of Albania, so the help of their mathematics teacher, as they called the German major in prison, was welcome.

After numerous formalities and verifications, the Albanian fugitives were allowed to stay in Greece. The German major, meanwhile, shortly after they had passed through Greece, had gone to the German embassy in Athens and from there had gone to Germany. (Remzi Barolli visited him several times in Germany and corresponded with him until 1983).

Remziu would stay in the neighboring country until the end of 1955 (the time when he had come to the USA). Immediately after arriving in Greece, he would come into contact with the CIA, a special chapter of his life, which will be discussed below. Memorie.al

The next issue follows