By Eugene Merlika

– Beyond the mists of history –

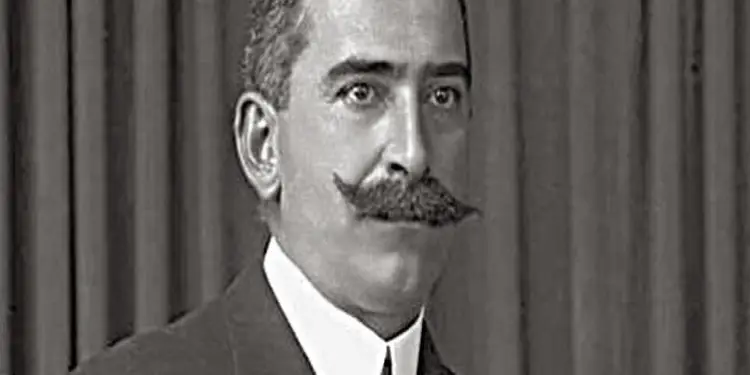

(Sotir Gjika and his family)

Memorie.al / It was the evening of March 25, 1925. Luigj Gurakuqi was having dinner at the Cavour restaurant in Bari with two of his friends and the wife of one of them: Riza Dani with his wife Makbule and his brother Dan Hasani. He asked permission from them, presenting the reason: I will go to Sotiri, because I promised a doll to his daughter. Sotiri was a friend of his, a compatriot, but who had Italian citizenship, as he had married a local girl.

Gurakuqi, that handsome and big-hearted man, failed to bring the promised doll to the four-year-old Elena, after the black bullet of Baltjon Stambolla, took his life so dear to Albania. His friend Sotir Gjika was supposed to speak at his funeral. But he too was sick and unable to leave the house. His wife Anxhela Kuarta spoke on his behalf, the faithful woman who stayed by his side until the end and who ended her life only with his memory.

Sotir Gjika was a well-known man in Bari. He wrote for the local newspaper and Il Messaggero in Rome. His house was the place where Albanian political exiles felt at home. Luigj Gurakuqi, Mustafa Kruja, Gjovalin Kamsi, Stavro Vinjau and other personalities who had chosen exile on Christmas night 1924 were welcomed in that house, when Fan Noli and his “revolutionary” experience were archived from history.

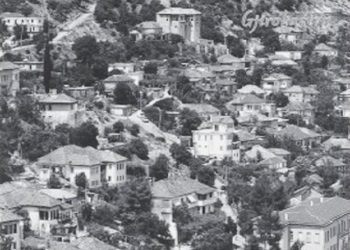

Sotir Gjika was not called a political immigrant. He was engaged in active politics for a while, but he was a publicist. The field of his activity absorbed food precisely from politics, especially in the first years after independence, when Albania’s fortunes had become the currency of the neighbors and the Great Powers. He was born on October 10, 1889 in the village of Shtikë in Cologne, the place where his ancestors, at the beginning of the 17th century, had stayed after fleeing from distant Spain and temporarily staying in the Low Countries and Germany. His mother, Lena, is soon widowed with two sons to rise. Living conditions were difficult in Turkish-era Cologne, and poverty was faced only through exile. The southerners were more inclined to look for another life, among many vicissitudes and unknowns, in the big world that started in Greece or nearby Turkey, with America as its goal point, from where many Albanians supported their families left in the Country of theirs.

The Gjika brothers left Shtika never to return. Before turning twenty, Sotiri left the village, his mother, with a great pain in his heart. He traveled to Egypt, where he had relatives who welcomed him. He then settled in Khartoum, Sudan, where he worked for some time. With the savings from that job and a help from his brother, who was stuck in Boston, USA, he crossed the ocean and joined his brother. Both of them opened a grocery store together and were noted for the continuous help they gave to the “Besa-Besë” Society, the Pan-Albanian Federation “Vatra” and the Albanian Autocephalous Church. They were years of intensive work in the service of the national issue, but also in terms of intellectual formation. Sotiri had not continued his higher studies, but was an autodidact with steel will, with sound and strong principles.

The year 1912 came. The idea was born among all Albanians that the aspiration nurtured by whole generations, in long centuries of captivity, that of freedom and the independent Albanian State, was approaching the restoration. This idea struck a chord with Sotir Gjika and made him end the American experience and return to Europe. He came to Italy, to Milan, where he participated in the Italo-Albanian Committee, created there with the aim of helping the national issue. As a delegate of that Committee, he participated in the Congress of Trieste, which gave the “blessing” to the historic initiative of Ismail Qemali and Luigj Gurakuqi, to declare the independence of Albania.

Independence also brought a fierce clash of thoughts in the political class and in the Albanian patriarchal society of the time. The problem that was posed forcefully in the political and social environments of independent Albania was the path that the country had to take. A good part of the ruling class consisted of former functionaries of the Turkish Empire, connected in mentality and culture to the Eastern world and its laws. Another part was inclined towards the West, from European culture and aimed to put Albania on the path of Western civilization, putting a clear limit to the Turkish influence on the new Albanian State. In this group of intellectuals, supporters of the experiences of Western political culture, there was also Sotir Gjika who, in 1913, when the entity of independent Albania was recognized by the Conference of Ambassadors in London, came to Vlora. He was so enthusiastic about the European future of Albania that he committed himself with all his forces to the benefit of Prince Wied as King of Albania. If his figure and role were strengthened above all parties in the diverse panorama of the political and administrative life of Albania, if the favorable presence of Europe in its destinies was more concrete and tangible, this would be a guarantee sheet for the future of the country.

In March 1914, Sotir Gjika, with a gun in his hand, fought in Rashbull, alongside Colonel Thomson, against the Essadist and Qamilist rebels, who wanted to restore “father’s dovlet”, i.e. the Turkey of the Sultans. At the front of the war, he was injured along with others and was saved by the energetic intervention of the representatives of the Great Powers, leaving for treatment in Italy. The participation in the nationalist youth struggle, in support of the King appointed by Europe, was rewarded with a medal that He presented to him, as a sign of gratitude, on which the date March 26 was marked. It was the spring of 1914, the threshold of the beginning of the First World War and one of the most difficult periods for the new Albanian State. He, with his mind and heart close to the troubled Motherland, would start a new life in Italy that of a journalist, through which he would provide a fundamental help for the benefit of the Albanian cause.

August 6, 1914 was a marked day for Sotir Gjika, that of entering the great world of journalism, specifically in the editing of an “Albanian newspaper page” in the daily organ of Bari, “Corriere delle Puglie”, which later becomes “La gazzetta del mezzogiorno”. In fact, he had earlier started that path with articles in Albanian press bodies outside the Motherland, such as: “Liberty of Albania” of Sofia, “Atdheu” of Constance or “The Sun” of the USA, in which he had published articles starting from 1911. The collaboration with the Italian newspaper was a gift from Captain Kastoldi, Prince Wied’s adjutant, whom he had known during his political and military activism in Albania. Kastoldi, also in love with the Albanian issue, thinks to serve it by publishing a newspaper page, dedicated to its problems. The young Sotiri saw the right experience and was well received and encouraged by the well-known journalists Kasano and Axarita, who taught him the art of journalism, helping him so much that, in a short time, he became one of the most prominent Albanian representatives in that field .

“Even though it was printed in an atmosphere not so favorable for Albania’s fate and torn apart as after the Treaty of London (1915), signed by the Covenanters, that “page” and that “feather” did not stop trumpeting the world, Albania’s right to ethnic borders against the interests of those interested in the predatory decisions of the Beslidhuns. I do not spare with harsh articles not only the enemies of Albania, but also the friends when the interests conflicted with those of the Motherland”, writes Gjovalin Kamsi in the article “Sotir Gjika”, published in the newspaper “Vulllneti i Populli”, on October 24, 1930 .

At a party organized in Rome in 1916, the young journalist meets a young girl from the south of Italy. The girl’s name was Anxhela Kuarta, she belonged to a well-known aristocratic family in Lecce. From this family came the well-known jurist Oronco Kuarta, President of the Supreme Court of Italy. At that party, the girl accompanied the great lyrical singer of Albanian origin, Tito Skipa, and sang with him, as she had a very beautiful voice. It was a strong love, love at first sight, love that remained so until the last moments of their life together, which, unfortunately, was short and did not last ten years.

The girl was originally from Celio Mesiatiko and her family had a monopoly on tobacco cultivation for the entire province. She had studied at a pedagogical school and graduated as a teacher. The marriage was quick and after it came the transfer to Rome, on Salaria Street, where Sotiri would start the publication of the newspaper Kuvendi, which soon became the tribune of the Albanian issue in Italy. The newspaper saw the light in the years 1918-1920, at a time when the journalist also collaborated with the Roman organ “The Messenger” (Il messaggero), for which he often went with services outside Italy. Sotir Gjika’s work in those years was of special intensity and usefulness. The newspaper had among its collaborators some of the best-known Albanian and Arbëresh publicists of the time, such as the director of the “La nazione albanese” notebook, Anselmo Lorecchio, professor Zef Skiroi, lawyer Kozmo Serembe, doctor Agostino Ribeko, Françesko Argondica, Kol Mellazi, Mustafa Asim Kruja, Lec Kurti, Kolë Kamsi, Kostaq Cipo, Milto Sotir Gurra, Mehdi Frashëri, Lef Nosi, Kostandin Kote, Visarion Dodani, etc.

From the Italian side, the newspaper relied on the writings of Federcon, Kastold, Axarita, Corrado Xoli, Prof. Benedetto de Luke, Filipo Naldi. Antonio Baldaçit, Sofia Mashit, Rozalia Adamit, etc. The newspaper became a bridge between Italy and Albania, between two peoples and two cultures. Its director, who already had Italian citizenship, worked hard to strengthen the friendship between the two countries. Sotir Gjika believed in the idea that Albania had to rely on Italy’s help on its way, that no other large country in the West had the interests to act for the benefit of our country, as much as Italy had. Geographical conditions and past history led to this path. This was one of the dominant motives of the beating of thoughts that, throughout this century of being an independent Albanian State, has determined many events and characters of political life.

In the distance of time and in a world that has changed a lot in its form and in its components, a colder, wiser and more dispassionate judgment can be given today on the essence of the controversy and the much-beaten thesis itself, without falling into the lap of demonization, as has often been done in the past. I think one thing should be kept in mind: all those men, who passionately discussed Albania’s strategies in different periods of the first half of the last century, had different opinions and perspectives. However, they all had a common goal, the success and progress of Albania. As such, they all deserve the gratitude and respect of the Nation today.

Sotir Gjika trusted him a lot and worked for the Italian-Albanian friendship even in those moments when the political actions of one or the other side damaged it. The newspaper ‘Kuvendi’ became the tribune of those ideas, just as it was the tribune of the Albanian issue, in defense of the territorial integrity and national identity in difficult times during and after the First World War, when the risks were really serious and great. . Leaving the floor again to Gjovalin Kamsi, regarding the Assembly, we learn that:

“For the spirit that gave it life, for the cooperation with the most prominent and mentioned members of Italian journalism and Albanian nationalism that it provided, that organ, small at the beginning, grew and became important among international political circles, which exceeded expectations”.

In these years of feverish activity in the field of journalism, Sotir Gjika also has pleasures in family life. His wife gives him two children, whom he christens Alexander and Elena. The boy’s name recalled the great King of Macedonia, who had Illyrian blood from his mother, while the girl’s name revived that of the mother but also of a vocal representative of his tribe, which had extended its presence as far as Romania, the princess Elena Gjika (Dora d’Istria). The children were born in Rome and then grew up and were educated in Bari, where the family returned after the closure of the Kuvendi newspaper at the end of 1920.

At that time, the Albanian issue was called stabilized and the Italian Government cut off the funds, as it deemed it unnecessary to continue publishing the newspaper. Keeping in mind the fact that the Assembly is financed by the Italian Government, the journalist from Shtika was forced to face the insinuations or criticisms that he suffered, even from his friends, in terms of maintaining the independence of judgment, objectivity and protecting the interests of the Nation Albanian from the side of the newspaper. Here is how he himself expresses himself about this problem:

“I deeply regretted this before you started it. I walked with objective philosophy…! I first carefully weighed the great needs of our cause to be known and boasted to the world, and then I weighed the harms and gains that might come to the national cause from a newspaper published with foreign funds: the gains seemed to me great. . So I got down to work, without looking around, without considering the difficult situation in which I voluntarily put myself”.

The director of the Assembly was a patriotic journalist, aware of the fragility of the historical moment of his homeland. Culture and experience in the field of journalism had taught him that the “fourth power” was often decisive even in decisions with historical weight in diplomacy or politics. Its purpose is the recognition and propaganda of the Albanian issue in Italy and Europe, the disclosure of the reasons and rights of the last nation in the Balkans that had come out on its own, the condemnation of the intrigues and feuds that were carried out behind its back. For this, he needed a tribune and people capable of speaking to the European public opinion from its square and convincing him of the truth of the arguments and the justice of the demands.

He wants this opportunity with a newspaper that could be published in Rome, the “lens” capital, through which Europe looks at Albania, and that could be financed by the Government of this country. He knew that this fact did not sound good, that it was revealed to an X-ray examination by an extremely demanding opinion, sometimes harsh and one-sided, that was ready to smear for nothing. But it was not the steppes; the interest of the Fatherland was stronger and pushed him forward in avoiding hesitation even if he risked something in his personal plan.

He passionately entered the work for the newspaper, absorbing the cooperation of the best-known Albanian and Italian journalism firms, with the clear and determined aim of presenting the Albanian issue in the true light, especially in relation to the proceedings of the Versailles Conference. , and to provide full assistance in strengthening the friendship between Albania and Italy. These are exactly the two dominant motives of the political thought of the director of the Assembly, who also took the title of the body from the past of his compatriots who, in the stormy waves of history, had found the strength of resistance in those gatherings of men which were baptized “Assemblies of Arberit”.

The national issue and Italian-Albanian relations constituted a binomial that inspired the writings that filled the pages of the newspaper. In those writings there are no humility, complex of the small and the poor who reaches out for alms. Friendship was conceived as in the mountains of Albania; the friend is put in charge of the country but never becomes the master of the house. The Assembly does not spare the flogging for the wrong policy of the Italian Government towards Albania. This was the best answer that Sotir Gjika could ask for those who said that he was running the newspaper with the money of the Italians.

In moments of crisis between the two countries, such as the Italo-Greek agreement (Titoni-Venizellos) on July 29, 1919 and the War of Vlora, the position of the Assembly was on the side of Albania. This is not only for the strong patriotic feelings of director Gjika and his associates, but also for the sake of historical objectivity and the natural right of the Albanian issue. This is what the director of the Assembly said on the occasion of the signing of the Tirana Protocol on August 2, 1920, after the Vlora war led by Qazim Koculi:

“The event of Vlona was caused by people who showed with their work that they were much smaller than the heavy and delicate rank they had assumed; for five years or so they kept Albania heartbroken from Italy, and so strongly broken that it comes to one’s mind to say and believe that a raging wind had completely taken the minds of the men of the State who ran it the fate of great Italy from the death of Di Sangiuliano until the day Giovanni Giolitti returned to power. Albania and Italy have now found their minds, they have found the good path again, and as soon as they find it, they will necessarily walk this path, both together towards new horizons and towards the new future. We have never doubted that Italy and Albania would one day go down this fateful path: our work of six years of journalism in Italy shows it. Our strong belief that Italy and Albania in the Adriatic and the Balkans can only live for each other, was never shaken by the bad policy of the Consulta against our country, nor was it shaken by unreasonable trends in some Albanian regions, the work page is not patriotic, it is Albanian. The day of triumph and fraternization of the two peoples came so quickly that it was not expected. Our work took its place: we have not labored in vain.”

These sentences, this part of one of the many writings of the Assembly, clearly prove what was the central axis of the worldview of the well-known journalist from Cologne, what were his political convictions, what were the criteria for evaluating events and problems, what was the leitmotif of his publicistic activity, which was the vision of the future and the strategic image of the relations between the two shores of the Adriatic. He remained loyal to this vision until the end of his life and was not lucky enough to see the storms, ebbs and flows that the history of Italian-Albanian relations would reserve in the following decades.

With the closing of the Assembly, in October 1920, the journalistic activity of Sotir Gjika, directly at the service of the Albanian national issue, no longer has its own forum. He continued to write in Messaggero and La gazzetta del Mezzogiorno, but also in Albanian notebooks such as Agimi etc. Then the family returned to Bari where he continued working in the city’s newspaper.

On August 27, 1923, the Italian general Enriko Telini, chairman of the International Commission for Determining the Albanian-Greek Border, was killed on the Janina-Saranda road. The murder was carried out by the Greeks and was widely reported in the European press. Sotir Gjika was sent by the newspaper he worked for, “Il messaggero”, to the country to investigate the perpetrators of the murder. There he got sick and since then his health went downhill. Although he had a strong physique, the incurable disease soon made him bedridden. These were the most difficult years of the journalist’s life, now known throughout Albania. He was aware of the untimely tragic end towards which he was irrevocably headed.

Next to him were his young wife and two small children. He was tormented by the thought that they would be left without any support and without any wealth to afford life. With his small salary as a journalist he had only been able to meet the demands of life, but he had not been able to put anything aside. Extremely generous by nature, during his life he never spared to help, often beyond his powers, his friends and colleagues who were in difficulty. He did these good things and always threw them under his wing, without making them known. Here is what Gjovalin Kamsi, who knew the native journalist closely, writes:

“…How many have been his good deeds that are known and unknown, how many times he has given to the poor and the rich, and no one has a day. Today, they probably don’t remember the time when Sotiri was their older brother. An ardent patriot, a righteous man, invincible. He convinced every opponent of his ideas. His motto was: “I served my country with faith and honor”. The cases that his father has not missed and they have been many, the big ones, he would have been rich if he wanted to, but he did not taint them among the deeds that were less than honest. Who dared to promise him (and it was at the time when the disease took him in charge of his duty as a journalist for the discovery of the murderers of General Tellini, he was bowing to the oak tree, why he died on April 12, 1927, in the solitude of a horse), a life of prosperity, not the orphan as he lived with that small journalist’s salary, only if he put his feather in the service of a moment that opposed him with his faith, with the national ideal, he had no answer: “I saw my hands cut off because I broke my promise. I will die poor, but I must die with honor. The child will inherit the inheritance from me, I know it well, but let’s live with honor. And for that I am proud”.

After the political testament, which was based on the strategic vision of an Albania that would walk on its path of recovery and progress thanks to close and friendly relations with Italy, we have his moral testament, in which the words “Faith” “Honor”, are written with a capital letter and are taboos that cannot be overcome even at the cost of life. A few decades have passed since the time when personalities of such moral stature represented our country in the various fields of social, political and cultural life. It seems to us that we are light years away from the reality of a country that occupies one of the first places in the world in terms of the level of illegality and corruption. Surprisingly, with all the progress made in these ten years in the various fields of economic or cultural life, we encounter a pronounced decline in terms of the moralization of public life. This has its own different reasons, but it seems to me that one of them is the obscuration that, for half a century, the communist regime did to the outstanding figures of the Albanian history of the last century, who would have been, thanks to the integrity of their moral and patriotism, reference points and beacons of light for the formation and education of Albanians.

Sotir Gjika closed his eyes, as stated above, on April 12, 1927, in a sanatorium and was buried in Verona at the age of 38. His family continued to live in economic difficulties. The widow, at the age of 35, connected her life with raising and educating her two children and with the memory of the man who loved her and respected her for his moral and intellectual qualities. She worked in her profession as a teacher and with her salary, she took the family forward. She had to seek the intervention of Prime Minister Mussolini to have a half pension for her two children. They grew up and were educated, completing the university, the boy for medicine and the girl for literature. The boy remained in his birthplace and created his own family. The girl would come to Albania as the bride of the son of one of her father’s closest friends, Mustafa Kruja.

I tried to describe briefly, as much as I could, the life of a patriotic journalist, with an important help for the benefit of the Albanian issue in some of the most delicate moments of its history. In 1934, the people of his native village had named the primary school after him, the name of the most prominent man they produced. The official history of the “academics”, of the communist regime and recently, even the encyclopedic dictionary of Mr. Robert Elsie, completely ignored it, creating a “debt of honor” that Albania remains to one of its outstanding sons. This “debt” would be washed away, bringing his work to light, collecting and publishing his writings, giving him the deserved place in the history of Albanian journalism, which seems to me to be the “orphan”, left aside from attention of our culture and historiography.

For almost half a century, the communist dictatorship covered with fog and mud many values of the culture and tradition of the Albanians. The new age, as an archaeologist, must discover them and restore them to the place they deserve. This is one of the main tasks that our culture, especially the new generation of researchers, must complete, for the benefit of the country’s image and in respecting the historical truth. Memorie.al

May 2006