By Eugjen Merlika

The fourth part

A life under dictatorship

Memories of a “class enemy”

Continued from the previous issue

Memorie.al/After the arrest I presented myself to the investigator. This was a young boy from Skrapar. I did well with the investigation with him. Unlike many of my friends who hated their investigators, I for Bashkim Caka, do not have the slightest anger; if i meet him tomorrow i can hang out with him and have a glass of beer. The tension of the first days for the accusation was replaced by complete disappointment when I learned that my close friend was the main accuser for my crime of “agitation and propaganda, for undermining and overthrowing the popular power”.

Our life passed before my eyes like a movie. Our acquaintance dates back more than a quarter of a century. We had been classmates together since the first high school, suffering comrades in the same conditions of internment. We had shared together the bite of the mouth, the joys and sorrows. Indeed our paths parted because he became a teacher and went on to university by correspondence, while I became a bricklayer and could not afford to go on to high school. But we remained friends, friends. There was no table to be laid in my house without his presence.

I had no doubt that after his behavior by Urjah Hippie was hidden infidelity, I could not imagine that my friend was erecting the building of his social position as a teacher on the ruins of my misfortune or that of other comrades. When he was a soldier, every time I helped him, I was with him in the tragedy of his father’s imprisonment. He was smart, cultured, and full of kindness and compassion to the people of my family; how could he bury me? In the name of what ideal did he achieve in this social abyss, how did he sleep peacefully in his marital bed? How did he endure the innocent looks of my little ones? How could he stand in front of my mother, whom he said had a lot of respect? Did Macbeth Hell exist for such types?

A host of such questions hit my brain in cell loneliness and there was no answer. I got the answer in dealing with him in the presence of the investigator and another officer, operative of our area. He maintained composure to the point of cynicism, was adamant in the assertion of the lawsuits he had made for several years. His conscience did not seem to kill him at all; on the contrary he was proud because he did a great service to the Party and the State. His determination went so far that his wife also testified to our conversations, an irregular procedure from a legal point of view, but acceptable to our investigation and court.

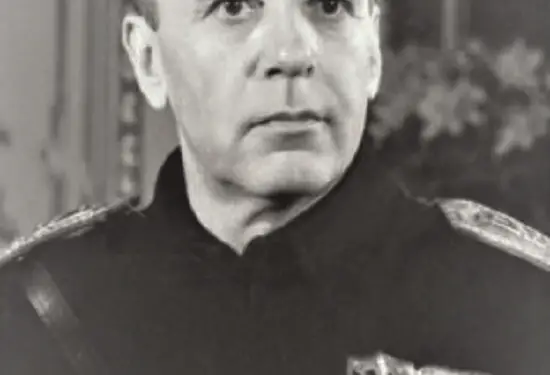

I had the real confrontation with the dictatorship in the conversation with the chairman of the Internal Affairs Branch, Kapllan Shehu, a typical personification of the born criminal. He was the brother-in-law of Kadri Hazbi, then Minister of Defense, and cut his sword on all four sides. He demanded from me a detailed report of all the conversations I had had during the twenty years with acquaintances and strangers, he demanded that through me he put other people in prison. This was the usual practice of his craft, a practice that many people have personally tried.

In my objection, he said: “Not only will you rot here, but I will bequeath it to your children to end up in prison. The family will be interned in Grabian or Bedat.” I have not encountered such sadism in any page of the book that has fallen into my hands; I believe it does not even exist in the famous Moscow processes of the thirties. This was the real face of the representative of the red dictatorship of the Albanian brand. Ironically and by the will of God, this man ended up in prison himself after three years of this conversation. There he recognized on his back what violence was and tried the beating of the prisoners, against whom he had exercised violence.

Why was I convicted? Some of the charges were:

- I had said that my grandfather had had patriotic activity until the time of the occupation.

- I had said that we could not resist a military attack by the superpowers.

- I had said that Albanian women do not have the emancipation of European women.

- I had expressed the opinion that of all the professionals, the teachers seemed to me the most incompetent in their work.

- I had heard the Pope’s message on the occasion of Christmas.

- I had read Dostoevsky.

- I had said that a person who has eight children is not to blame for the State’s poverty.

- I had comforted my plaintiff on the occasion of the shooting of his brother-in-law with the expression: “This was his fate”. He interpreted it as if I had accused the Justice authorities, that they convicted him in vain. Surprisingly, I was more upset than the plaintiffs, even though I did not know his brother-in-law at all.

- I was fatalistic and believed in the existence of God.

- I had said that the class war is fierce against us, as they do not even let us work in the craft of masonry.

- I had said that life is better in Italy than in Albania.

These and other conversations that I do not remember constituted my “crime” against the State, for which the trial court decided to sentence me to eight years in prison. What should be noted is the fact that I had these conversations with only one person, after no one else confirmed them in court. The reader can imagine what a “danger” the government posed to them and how “credible” the “popular” justice was, which had removed the institution of defense counsel as “unnecessary and useless”. I remember a nice phrase from the presiding judge who said to me about Dostoevsky, among other things: “I read it too, but what did you say to this one” pointing to my witness!

After my sentence, Kapllan Shehu and Kosta Ndini continued the criminal process against my family. The mother and wife were deported (the father was on time deported) and one day the car went to the door and loaded the luggage. My family ended up in Grabian, a hillside internment site, eighteen kilometers from the city of Lushnja. I ended up in Spaç of Mirdita. Spaci, already world-famous, was a natural prison. A pit between the mountains of Mirdita was chosen as a place of punishment by the former minister Koço Theodhosi and, ironically, his imprisoned brother was there. There I met my friends who had been arrested before me and got to know others. It was an overcrowded camp in the late 1980s, a place of terror where sentences and re-sentences were in place, where the special regime established after the uprising that broke out there in May 1973 was maintained.

There were people from all characters. There were those who for more than ten years in that hell faced suffering with admirable dignity and imposed respect. There were those who paid the price of their honesty because they had not accepted the dictates of evil in their character, but there were also those who were the embodiment of evil; a prisoner who was engaged in reading the press, had observed a shepherd in a tent in front of the camp who did not respect the schedule of goat removal and had signaled, with a letter about this phenomenon, the Party Committee in Rrëshen; a brigadier, sentenced to twenty years, sued the police officer in command that he did not come to force the prisoners to work; others, prisoners in Zejmen, wrote to the Ministry, that the commissar treated the prisoners well at a time when he was doing his duty, but with the people without rudeness. These guys make life there harder, add to the suffering.

Working in the mine had its difficulties. Five months in the gallery unjustly (I was sick with duodenal ulcers and I should not have been admitted to the gallery), on the most difficult fronts I was provoked by a severe stomach crisis, which I could barely cope with with the medicine my uncle sent me from Italy . At every start of work, I prayed to God to save me, and thanked Him when I went out. I have escaped danger several times. I was unloading the wagon in a gallery when the crash happened right where I was loading. Next month on that front a boy from Shkodra was killed. Tragedy was near at every moment, but man gets used to the evil and no longer impresses. I stayed there for a year and a half, and one day in May 1982, I moved to Zejmen, where a new camp was being set up. The conditions there were very different from those of Spaç, and we thought we were half free.

Life in prison is a cripple for man. Deprivations of all kinds, distance from family, preoccupation with it, line up several times a day, the thought of being innocent inside, all these create a spiritual complex that darkens man, gray him prematurely, and obscures his thought. No wonder Dostoevsky called it the “house of the dead.” But what force keeps him alive, that when he is sentenced to twenty years in prison, if he knows that he will go crazy or kill himself? There is only one cure: hope, it keeps people strong, it makes them face evil with gas. Hope begins in man from the moment he enters that door and accompanies him all the time.

So we waited for the release at every holiday, and the first moment of despair for his absence was replaced by the hopeful anticipation for the next holiday. Thus in November 1982, God gave the good will to Enver Hoxha to decree the first pardon in twenty years. That apology included me. Life is a union of good and evil. We did not feel much joy for the release because we left our friends in prison, with whom we had spent moments of despair, pain for dead relatives, we had found solace in each other’s words and now, it seemed to us that yes we betrayed them by leaving them there, inside the wires.

I returned home that day in November 1982, with my head shaved (the deputy camp commander had given a firm order to shave a week before his release, although the decision made by the leadership was known), with a bag in hand, with lost eyesight in those fields, which reminded me of tedious work moments and under curious eyes and with different expressions of people on buses and on the streets. The people of the house came in front of me, my mother sat down and kissed the ground, the children were thrown around my neck, my father hugged me, my wife, and my brother-in-law. Tears, congratulations and a little gas.

Two and a half years away from the family, how much misfortune and pain had fallen on him, a period beyond the ordinary on the shoulders of those children and the elderly. Years laden with sickness, death, police oppression, class hatred, extraordinary hardships of life, lack of support. I had to close a lot of wounds now, but did I have the strength? The first action I took as soon as I got off the bus in Lushnja was to visit the good grave of my good grandmother. God did not want to give me a joy in the end, my release. Before the eyes of the mind she is alive every day for me, I loved her very much, more than my parents, and the last look of our meeting is ingrained in my brain. He came and met me at the investigator after my sentence, along with the young children, father and wife. She gave me courage and repeated more or less the words she used to say to me when I was little when I cried inside the cell, and she was fighting with the policeman outside.

My honorable grandmothers, the objects of love, the infinite compassion, how much you cared for me, how much feeling you poured on me, as if you wanted to compensate, you, the only ones, what the world and destiny gave with drops. One raised me with her hands, took the bite out of my mouth and did not let my stomach ache from hunger; she was the first to introduce me to the history of thirty years of pre-war, to the true history of my Country. It was a living encyclopedia, talking in detail about prominent historical figures, about wise men, brave and noble, to whom he had so often made coffee and set the table. He told various events and conversations, about Noli and Ahmet Zogu, Avni Rystemi (she used to say that), and Abdi Toptan, about Bajram Begun and Hasan Prishtina, about Ndre Mjeda and Patër Gjergj Fishta, about Zija Dibra and Elez Isufm, for Stavro Vinjau and Qazim Koculi, for Bazi e Cana and many other men who had tried to lay the foundations of this nation in difficult years.

But above all, the figure of Gurakuqi stood out in her memory, a man who, out of nobility and wisdom, had rare friends. I have many episodes of his taste in my mind that she often mentioned: “Eh my Caje, it’s his fault, pointing to my grandfather, I told him in time not to get married, in Albania there is no politics to have a family “. How prophetic, how wise, how profound this expression of that man who never married and who answered the question about this: “I am married to Albania”. How much this century proved these words, how much we paid for them, even I the consequences of that political life of her husband. How far behind civilization was left our society, which terribly discharged on innocent women and children the consequences of the passions, ideas and political life of the protagonists…!

The figure of Luigj Gurakuqi connected me with my other grandmother, the widow of Sotir Gjika, publicist and journalist, director of the newspaper “Mecli” which was published in Rome. On that fateful night of March 2, 1925, Luigi, after having dinner at a restaurant with a friend, told him that he would go to Sotir because he had promised his daughter a doll and would bring it to her. But the cruel bullet did not keep that generous man from fulfilling his promise. Sotiri would speak at his grave, but unable to get out of bed, my grandmother, my wife, spoke instead.

My grandmother, who could not know me until she died, who spent her whole life struggling to educate her two orphaned children, who sacrificed everything to build a future for me and, finally died knowing that Poçi i her, had ended up in jail. After a year she also took my uncle, and so for my mother was extinguished the last hope of finding a home of hers, with which she was now connected only by memories and graves. Dictatorship would weigh painfully on people’s divisions, my mother left the family twenty-three years old to no longer meet her people. I believe that there must be a divine justice, before which those who built such an order of things must answer…!

My return home had to restore a minimum of calm that was lacking during my years in prison. In the innumerable difficulties of these two years, only my uncle with his wife and the wife’s family stood by my family. Only they knocked on my door without fear at the door of Spaç or Zejmen, they tried with their presence to alleviate the wounds a little. In such circumstances, the nobility of one who is near is an ointment that has not been paid with all the gold of the world. The woman’s parents and brothers did not abandon her sister in adversity, did not offer her the opportunity of separation, even formal, as hundreds of other families did, causing hundreds of dramas with devastating consequences for the feelings, personality and spiritual world of prisoners, children and their families. They supported her, comforted her, stood by their sister with courage and, ignoring the potential danger that might come to them from the consequent development of class warfare by people without any moral principle per se. To these people who gave proof of kindness in the darkest hours of the long night of dictatorship, I owe you forever.

Early release from prison was returned to exile in February 1984 by the Exile Commission, without any motivation. A simple communication from a Branch employee, in the pompous presence of the Council chair and the Party secretary certifying the “humane” act, put me in a second prison, but without barbed wire. It was a new fashion at that time, an internment campaign of an ordinary character, to hit foreign shows with social dangers such as theft, immorality, etc…! I was involved in this field along with many others released from amnesty. Would we complete the number planned by the Ministry of Internal Affairs or would the party and the state view with regret their “generous” act of our release from prison?

Internment in those years had the character of a detention. Very strict rules conditioned daily life and brought great difficulties for moving and family needs. Everyone in the house was interned and the consequences were felt a lot, especially in health matters. Here I want to tell some painful episodes. The first has to do with my second daughter, Elena. At the age of five, she developed a severe abdominal pain that plagued her almost constantly. The area doctor suspected parasites for months; she took all sorts of pharmacy and folk medicine drugs, but to no avail. The sufferings of the desolate child, who spent occasionally and sleepless nights in our arms, troubled us immensely. Seeing the condition of the child and the unsatisfactory result of the treatment, the doctor decided to hospitalize him in Lushnja.

Wanting to take him to town the next day, we asked for permission from the person appealing to us, who was the council secretary. But this person, certainly in agreement with the Department of Internal Affairs, manipulated the doctor to such an extent that the latter the next day, came out with the opinion that the child does not need to be hospitalized. This was because I had no right to go all the way to town to carry the baby. Let the reader judge for himself the mental state of a parent, in such conditions. As a result of the inability to take the girl to the specialists, she became chronic with a kidney disease, which was discovered a year later by Doctor Polikron Çela. I am very grateful to that doctor for his outstanding care and humanity in performing his duty. Some time ago I read in the newspaper that someone had shot this prominent doctor by breaking his arm. I do not know who he was, but I am convinced that he will be the ideal friend of those who did not want my child to be healed, I was very sorry; something stabbed me in the soul…!

My mother suffers from a collection of diseases; the very conditions of her life have stimulated their emergence. At the time she was interned in Grabjan, she was forced to be hospitalized twice, in the last degree, by her kidneys and heart. The first row was the nephrologist Fatmir Dabulla, under his patronage. I had to deal with him on the issue of the girl, he had recommended me her visit to Dr. Polikron in Tirana and from time to time he controlled it himself. The mother was having a severe pyelonephritis crisis, about to undergo azotemia. The doctor visited her carefully, sent the nurse to do the proper analysis, and then with serious professionalism explained to me, the serious condition of the mother. We did not have much confidence, he remembered me a quarter of a century ago in school, even though he had been a few years behind me. I explained my current situation, how I could not be near my mother, except when the Department of Internal Affairs gave me permission to go to the city.

She did not react with words, she became very serious and assured me that she would use all the right medications and in about two weeks she would stabilize her health condition…! So I parted with him with confidence in his words. But after about ten days I was called to pick up my mother. How could he have healed so quickly? I am given permission to go along with a friend of ours who was no longer interned. I meet Fatmir and ask him how the matter is. The frown on his face presses on himself and he is unable to give me an answer. Yes, I read it myself in his face, in that face that a few days ago was full of confidence that he would be able to do such a difficult job, the healing of a man. Now I read in it the disappointment, the pity for the patient, for me and of course the pity for himself…! He, as a doctor, had to look at his patients differently, he had to serve them according to their social and political position, according to their “class” affiliation, and he had to violate the first article of the great book of the world of Medicine, the principle of Hippocrates. “To be a doctor, you have to be human first.” He gave me the prescription for gentamicin, a powerful antibiotic he had started to inject into his mother, but which two days later another non-specialist doctor had ordered to be discontinued.

What was this “doctor” or better to say ‘butcher’, who had given the order to stop the treatment without leaving the hospital? I do not want to mention the name, such names tarnish the writing, and they should not even exist in people’s memory. He was a member of the ALP, was the head of the ward, a kind of policeman of the medical institution, educated thanks to his kinship with a great lady of the regime, and was charged in the hospital to wage a “class war”, beyond any principle a person who also knows the death row inmate, the right to medical treatment or service before execution. What impression would such a fact have made on Marx? This society designed by him, to “correct” the injustices of the capital world, how beautifully it would coincide with such phenomena that illustrated its socialist “humanism” on the eve of 2000…! Memorie.al

The next issue follows

![“Count Durazzo and Mozart discussed this piece, as a few years prior he had attempted to stage it in the Theaters of Vienna; he even [discussed it] with Rousseau…” / The unknown history of the famous Durazzo family.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/collagemozart_Durazzo-2-350x250.jpg)