By Taisa Batkina Pine

Part fourteen

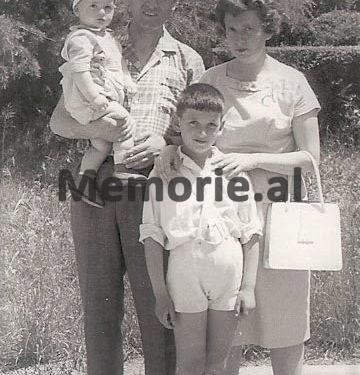

Memorie.al/ publishes the unknown story of the Russian Taisa Batkina (Pine), originally from Tula, Russia, the third child of a very poor rural family, who was left an orphan at a very young age, after her father lost her life while working in one of the coal galleries on the outskirts of Tula, where he worked as a miner (shortly after escaping arrest, accused of “supporting the enemies of the people”) and she grew up with difficulty great economic, as their city continued to be under the bombardment of German forces, which had reached as far as near Kursk. Taisa graduated from the Faculty of Chemistry, near the ‘Lomonosov’ University of Moscow, where she met and married the Albanian student, Gaqo Pisha, originally from the city of Korça, who at that time was studying at the Faculty of Philosophy in Moscow and both together in 1957, they returned to Albania, together with their newborn son, Sasha, and began life in the city of Tirana, where Taisa was appointed as a professor of Chemistry at the State University of Tirana, while Gaqo, in the chair of Marxism- where they worked until 1976, when the State Security arrested Taisa Batkina on fabricated charges, accusing her of being a “Soviet KGB agent” and sentencing her to 16 years in political prison, which she suffered. in the “Women’s Prison” in the city “Stalin”, from where she was released in 1986, while her husband, Gaqo Pisha, had died in 1983, from a serious illness. The tragic story of Taisa Batkina (Pine), in the inhuman camps and prisons of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime, where she spent a decade of her life, along with many compatriots from the former Soviet Union, or other Eastern European countries, comes through her memories, published in a book entitled “We hoped and survived”, memories which, her son, Aleksandër Pisha, kindly offered her for publication, in Memorie.al

We hoped and survived

I dedicate it to the bright memory of my husband, GAQO PISHA

This is a book of memories. In it I want to tell about my life and that of my friends, Soviet women, who tried prison for several years just because they got the courage and got married and linked their fate with that of Albanian students. The prison was part of the great GULAG in the small Balkan country, Albania, where for many years the bloody communist regime of Enver Hoxha ruled, who was a loyal student of Stalin and a follower of his cause.

Through this book I would like everyone to learn about the inhuman trials we experienced and the horrible years we spent in Albanian prisons, just because we… fell in love! And let no one ever forgets what totalitarianism, despotism is and what the consequences of this system are.

Continued from the previous issue

1982 Amnesty

A special commission came to the camp to acquaint us with its conditions. (I find it extremely difficult to write, my memories drowned me, I kept everything closed in the depths of my soul, covered by another life, other impressions… as forgotten, but very, very painful). We were all gathered in the large canteen of the ordinary corps. The chairman of the commission started reading the explanations regarding the decree… or, perhaps, its content… I do not remember well. Vola and I were in the hall and suddenly realized that our article was not included in that decree. Something black, scary rushed towards me, took my breath away, squeezed me to the ground. I had to do my best to hold on, not to fall and not to scream. Ina Shahe, who was sitting in the yard and looking out the window, later told me: “Your face expressed such horror that I cannot tell.” We barely got out of the canteen, went to our corps, lay down on the bed. Six women were released from “our Soviet squad”, and many were released throughout the camp. Among them were elderly women, old women, women with small children, convicts with short prison terms, etc. The camp was divided into two groups: the lucky ones, who would be released, and the unfortunates, overwhelmed by grief, which did not benefit from the amnesty. Many of the latter fell into depression, lay in beds, covered their heads and feet, did not talk to anyone, did not eat.

November 28 and 29 were holidays, we did not work, and on the 30th the release took place. The women who would come out would come around, collect their belongings, and distribute what they no longer needed. By nature I am an energetic person, I find it easier to experience grief, misfortune at work or in relationships with people. I cannot lie down, suffer… this would eventually bring me down. Throughout the day of November 30, I helped my friends prepare, I carried their belongings, I greeted them. Suddenly they tell me I have an appointment “Meeting”?! Poor my dear people! They reminded me that they would release me too. I ran, came out of the gate… and saw Sasha. He told me how long they had been waiting for the amnesty. He had gone to Berat, to his cousin, to be closer to the camp. Now he came to calm me down, to relieve me. “How did the father receive the amnesty, how was he waiting for you…!”It will be very difficult now,” Sasha told me. Yes, indeed, poor my sick Gaqo! How he needed me, my care, my help! They lived three, three men; they had to do everything themselves, and my husband, once so good, so strong, was now in a very serious condition. This amnesty, this dead hope for release, was another blow to my poor family. And Gaqoja could not stand this heavy blow. Six months later, he disappeared…!

Let’s go back to camp

Preparations, the mess continued. Before release they read the names of those who would come out. I also heard the name of Giuliana, “Italian spy”. She was seriously ill, it was clear that she was being released for health reasons, although she was not told, and her article was not included in the decree. We rejoiced for him. Suddenly Margarita, “the second Italian spy”, ran towards the door. She asked for a meeting with someone from the release commission and started shouting: “Why did you just release Juliana…?! We have the same article, the same accusations”?! They started the verification and canceled the release of Giuliana, who was meanwhile waiting at the gate to come out. When told she would not be released, she lost consciousness, collapsed and bled to death. We picked him up with difficulty, brought him to the corps, gave him first aid. Everyone shouted loudly, cursed Margarita, and the young girls started shooting him: “Can’t wait until tomorrow”? They said. – “Juliana would have run away, and you could then complain as much as you want”?! But now the evil had happened and could not be remedied. Among those released was the “pregnant grandmother,” as we called an elderly, sick, half-insane woman. At the end of the day he was told he would be out the next day. The thing is that a large amount of money was collected from her pension she received from Italy. (I will write about “pregnant grandmother” later). The command was afraid to take him out with the others, lest he be robbed on the way. They decided to start the next day by car. But the “pregnant grandmother” did not believe her, she stood by the door and cried. “They are lying to me; they do not want to release me. So they deceived me even when they arrested me, they told me that they would take me to the airport and put me in prison “…

Painful episodes

The main thing was that we requested a meeting with the chairman of the amnesty commission. He was a senior official of the Ministry of Interior. He agreed to wait for us. We went out of the fence… through the gate. There were those among us who, until the last moment, were afraid… the fear was stronger than the horrors of prison. To force them to come out with us, to make our general protest unanimous, Nadja devised such a ruse: she ran into the room and shouted: “All the Soviets are looking for them in command! Urgently”! They both had to come out, which was still going on. The chairman of the commission (I do not remember his name), an elderly man, an old employee of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, welcomed us all one by one with great kindness, listened to us attentively and told us to write down all that we told him, in great detail, in a letter addressed to the Minister of Internal Affairs. As if we had taken wings, we went out and immediately started writing. Nazif, the economist, who was present at the meeting because he was on duty that day, called me, handed me a pile of white papers and said: “Do not worry, you will all be released, give everyone a letter, let each one write. But Nazif was wrong. After a couple of months, we got the usual rejection, with the familiar, standard wording. This refusal was the last point, which killed the young Albanian girl, Mina, accused of “cow work”. (I will tell about this in more detail a little below). I think the purpose of the amnesty was to soften the atmosphere in the country somewhat. Enver Hoxha wanted to show that the repression did not come from him, but from Mehmet Shehu, Kadri Hazbiu and others.

Continuation of the struggle for liberation

After studying and assessing the situation, we decided that the only way that could help us to be released was the constant request for release, the constant letters. We started writing, without worrying about the rule, according to which you were allowed to write once in 6 months. And we sent them everywhere; in the Court of Tirana, where our trial took place, in the prosecutor’s office of Elbasan, in the district of which our camp was located, in the High Court, in the General Prosecutor’s Office, in the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Sometimes we wrote in Albanian, but more often in Russian, believing that more people would know about us, because the Russian text would be read by translators. Employees of many institutions and of different ranks came to the camp. Usually they entered the territory of the camp, gave lectures. After the lectures we put them in the middle and asked for their release. The lecturers were usually accompanied by the commissar, he shouted at us, tried to get away from us, but we kept screaming, asking for our release. But nothing helped us; we continued to stay inside, to work, to suffer the hard life of prison. After the amnesty, in the camp as if life began to be easier, people became significantly rarer. Our “enemies” got jobs in tailoring and wire making; some thin wire rings connected to each other. They placed them along the border. Deserters entangled in these flowers strings of rings and fell into the hands of the guards. But the new director created a difficult environment in the camp. He believed every report, made frequent checks, stopped what he could.

Distress

My people now seemed to feel more relieved. The eldest son started working in the foundry. Hard work, with three shifts, but the salary was something better than elsewhere. Costa, the youngest, worked and continued the Technical School, then was called up as a soldier. My husband’s granddaughter, Alma, now lived with them. The woman’s hand began to feel at home. I told you above that in the spring of 1983, I was admitted to the prison hospital in Tirana and my sick husband came and met me twice. In late July 1983, I was given an all-night meeting with Alma. We had a good time together, we talked about everything. Alma told me in detail how they live… calmed me down. But only after two weeks I was called back to the meeting. I was surprised and very worried. What happened? Why did they come to the meeting? I went out the gate. Towards me I saw Sasha and Alma coming. Alma was dressed in black. I started shivering. What happened? Gaqoja was sick…! Costa… soldier. I entered the meeting room. Sasha and Alma also entered. “Mom, hold on, don’t cry, Dad is dead… Dad is no longer with us.” I do not remember what happened next, I just remember sitting on the bench, I do not know, before or not, I remember the horror and the horrible emptiness that overwhelmed me. It all ended! I had dreamed so much all those horrible years that everything would pass, the iron door would open and I would go home. I will sit down, I will embrace all my loved ones and I will cry, I will cry, for everything that was accumulated in my soul, I will shed all the spared tears. And now I had no tears, they were frozen somewhere inside, they had hardened. My dear husband, my Gaqo, was no longer in this world. Gaqo had always been a good man, compassionate, wise, caring, honest and confident. He was calm and quiet. All the misfortunes, troubles, sorrows, griefs and threats that we had in abundance in Albania, he experienced in silence, he kept them inside. Our conditions were such that he was almost always under stress. Undoubtedly, this badly affected his nervous system and, surely, caused my healthy, strong, 44-year-old husband to get Parkinson’s disease.

I do not know what he thought when he was arrested, because we did not meet again, we did not talk alone, but I am almost certain that in his mind he blamed himself. It is as if I hear his voice: “It’s my fault, I brought him here. I could not protect it, I did not protect it”! All of this affected him badly. The meeting ended and I went back after the barbed wire. All my friends were gathered behind the gate. They helped me get to bed, calmed me down, comforted me. And not only them, the “Soviet women”, all, the whole corps, came, expressed their regret, calmed me down. The support of friends is a great thing. I felt very heavy, I could not calm down, I could not sleep, I was thinking at home and I could not do anything. I could not get out of prison, run home, and go to the cemetery. What could I do? Nothing! Just to stay, as I had stayed until that day and to survive. Two weeks later Costa came, they had given him a few days leave. He had experienced the death of his father very hard, he had loved him very much, and Gaqo also had many things in common with each other. When Costa was home, sick Gaqo calmed down and felt better. It was terribly hot that day. The boy had walked 20 kilometers wearing a military uniform, was drenched in sweat, with his gymnasts unbuttoned and his pants tucked into his feet Bag.

Suddenly the commissar entered the meeting room. “What do you look like, soldier?” – addressed Costa. “And died father”. “Do not lie”? The commissar asked with a wry laugh. Costa froze, ready to explode, punching the commissar. “Calm down, Costa!” – I called the boy in Russian. Commissar left. I was very scared; from that wicked man everything could be expected, he could make any accusation, he could even arrest the boy. I do not remember what Sasha and Costa told me during the meetings. Only later did I learn how Gaqoja had died. Patients with Parkinson’s do not die from this disease, but from others, which the weakened organism cannot resist. So it was with Gaqo. Before he died, he was very weak, shivered, collapsed, often had hallucinations. Suffered 18 years from this disease. Eventually, he contracted pneumonia and died in hospital. With the help of some of her own loyal companions, Sasha buried her father at the bottom of the cemetery. I decided to write to my people in the Soviet Union about my husband’s death, where I was, what was happening to me. For them it was a terrible blow. Then when the correspondence was restored, their letters gave me a lot of heart and strength to survive.

Death of Enver Hoxha

Meanwhile life in the camp went on. On a typical day, at the time when the brigades were returning from the fields, I suddenly heard the hysterical cries of a woman then others. From their oil I understood that Enver Hoxha had died. My soul is filled with joy. But I quickly collected myself, lowered my head, and closed my eyes, so that none of the spies could read anything in them. The last loyal student of Stalin in Europe died the tyrant who borrowed Stalin’s policy in Europe, his methods and ideas in Albania, who continued here for many years the Stalinist policy of the dictatorship of the proletariat and bloody persecutions. The death of Enver Hoxha gave us hope to be released. However, we realized that this could not happen right away; after Enver’s death power remained in the hands of his wife and collaborators. A few days later, Enver Hoxha was buried. On television, for several hours, they showed how the mortuary procession moved through the streets of Tirana. Along the streets, in the rain, under the open tents, stood thousands of mourning crowds. Yes, they did! For decades in the minds of the people, they had instilled the idea of the great leader, wise leader, righteous, infallible teacher, caring father of all Albanians. Implantation started in kindergartens and continued throughout life. Many understood, knew things well, but in the watchful eye of power, they were forced to lie, to pretend. I looked at the screen and thought of my dear husband, who was no longer alive, who could not be buried as he deserved that honest, hardworking and kind man, who could not accompany him to the last apartment and… cried, cried without rested. It was then that I really cried for my husband for the first time.

Second amnesty, release…!

They kept us in jail but the hope of being released grew stronger. The place of Enver Hoxha as the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the ALP was taken by Ramiz Alia, who until then had served as the Second Secretary of the K.Q. Ramiz Alia had family ties with Enver Hoxha and was thought to be a follower of his cause, even to protect family interests. However, as a personality he was very different from Enver Hoxha. He was an intelligent, reasonable, progressive man. I knew about his qualities from my husband, who had once worked with him. At the end of 1985, amnesty was discussed again. All those who came to meet the prisoners talked about it, wrote in letters, and even in telegrams. The date 13 January was mentioned everywhere. January 11 was a holiday, the day of the proclamation of the Republic, and the amnesty was to be announced on the occasion of this holiday. Our command also talked about the amnesty, about its conditions. Sasha came to meet me and when he found the opportunity he whispered in my ear: “On January 13 you will be home”!! I had a high mood; however, the fear did not leave me alone: what if this time too I am not released? I do not know if my strength would be enough to endure such a blow. The women prisoners, who had come out of the gate, or cleaned in command, or worked in the garden and communicated with the guards, brought us various words, that all convicts less than 15 years old would be released, then 18 years, then… starting from age, etc. Finally one of the guards told us: “Listen to the radio”! We followed the loudspeaker of the hall, which, I do not know why, rather did not feel that it worked. /Memorie.al