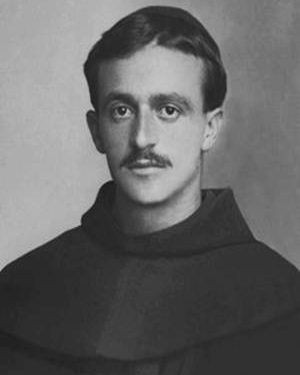

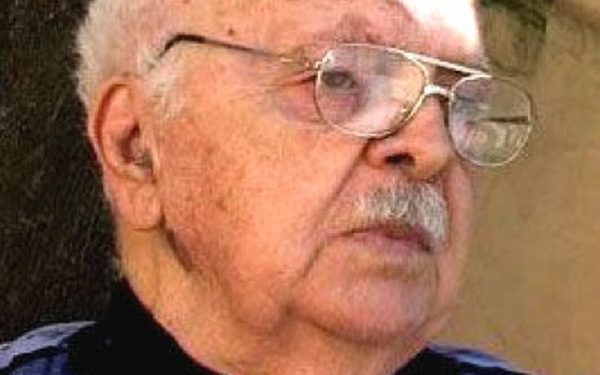

Memorie.al publishes some parts from the memoir of the author Ejëll Çoba, the well-known intellectual from the city of Shkodra, a sucker of one of the most famous families of that city, who after graduating from the University ‘La Sapienza’ of Rome in In 1932, he returned to his homeland where he practiced his profession, pursuing an administrative career, as ‘Dottore in Giurisprudenca’ and then for several years in the top state administration, where he also occupied the period of occupation of the country, (1939- 1940), where he held several senior positions, as Director in the Ministry of Justice, Secretary General of the Council of Ministers, Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs, etc. His arrest in 1946, (together with his brother, Kelin) accused of participating in the ‘Postriba Movement’ and after a long investigation in Shkodra and Tirana, was sentenced to 25 years in prison, of which he suffered for years and five months and five days in prison, in the horrible labor camps, all the way to Burrell Hell. The unknown memories of Ejëll Çoba, which come with an introduction by his fellow citizen, the well-known writer, Zija Çela, present to the reader a panorama ‘painted with the brush’ of pain, where details and details are given about his sufferings in the camps. of the prisons of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, as well as other accomplices, known and unknown names, such as: Father Bernardin Palaj, Guljelm Suma, Syrri Anamali, Ramdan Sokoli, Cin Serreqi, Father Karol Serreqi, Father Filip Mazrreku, Hamdi Isufi, Hafiz Ali Kraja, Beqir Çela, Musa Gjylbegu, Asim Abdurahmani, Kolec Deda, Nikoll Deda, Felatun Vila, Gjush Deda, Sali Vuçiterni, Emin Bakalli, Qani Katroshi, Sali Doda, etc., as well as some names of investigators, guards, State Security officers, such as Fadil Kapisyzi, etc.

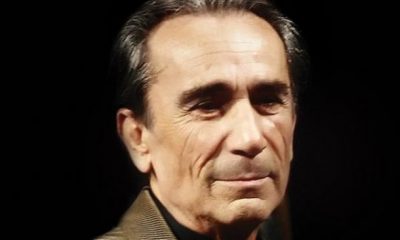

Preface to the book of memories “Life is lost”, by Ejëll Çoba, by the famous writer Zija Çela

A saved soul

The day the author lowered the pen, he probably felt he would lower his head as well. And when he was bowing his head to leave this world, as if the sufferings he had taken away no longer belonged to him, he did not ask for anything in return, nor did he leave a will for the crypt of the grave, only the question he had asked “But will there ever come a time for this people to rejoice?” I wish him well! ”

Due to his serious illness, Ejëll Çoba had already cut off the records and some of the other imprisonments, in Beden of Kavaja, in Orman-Pojanin of Korça or in the infamous Burrel, were still left unwritten. But on the last page, as in divine coincidences, he was talking about a short-lived friend of his, also from Shkodra and accomplice in communist prisons, the translator of Dante Alighieri. Conversations with the professor of literature pleased him, because listening to him, they turned him into an unreal life. He believed in God and, most likely, must have fled in the hope of finding Paradise beyond, but with the pain he was leaving Hell. At that time Pashko Gjeçi, the final character of Ejëll Çoba, continued the translation of “Divine Comedy”.

Whenever old parchments are discovered, few question their authenticity. Such memorials have something of parchment, because before being thrown on paper, it was previously written on the author’s skin.

The Book of the Angel comes as a gift from that angel, who has only one sovereign destiny: to hold the side of Innocence in all circumstances, even when the strongest has put his foot in the throat of the weakest. The bearer of right and justice, in all the mess of the earth, is man. So full of human values is the book “Lost Life”, so aggravating in justice in the face of injustice, that the accusations made by the regime against the author are turned against the accusers, not by covering themselves with propaganda, but by stripping the propaganda from the facts.

It seems that the messenger angel, the godly courier, had found the missionary in Ailean with the same certainty as he found the like among the champions. It is difficult to find a greater mission than one that gains function and becomes a document through experience. It is like the mysterious glow in the darkness of night that, starting from somewhere for others, burns itself but never returns to the source from which it comes.

A man of school and law, illuminated by Western culture, Ejëll Çoba crosses the right through the knife blade. And this epic transition in the face of torture and the death penalty, this spirit of determination not to burden oneself with guilt that he did not commit, but also to aggravate others on condition that he finds salvation, is one of the most peculiar features. sharp of the book. Ejëll Çoba was not an opponent who opposed the communists with weapons, nor an activist of Balli or Legality, he was not a speculative trader who made fat during the war and hid the gold coins, nor was he an industrialist whose wealth would be confiscated according to the model. stalinian. He was the intellectual who, after graduating from La Sapienza (1932), practiced the profession in his homeland, pursuing an administrative career. Ejëll Çoba, Dottore in Giurisprudenca, was condemned for his nationalist ideas and with his resistance, which convincingly resonates in these memories, he was told “No!” political trials of cruel genocide.

For the universal it carries, if not heard then, this cry of human dignity and political honor to this day is worth hearing throughout the former communist empire.

This book is full of spiritual and intellectual flow. A book that disturbs and disturbs awakens the self-examination of the reader’s conscience, the examination by the self up to the level of national consciousness. The author prefers to confess, to confess intensely. And throughout the narrative, from the gift that reminds the novelist, the rhythm, the extensive Albanian dictionary (quotes in Latin, Italian and French), the short style and the meticulous sensitivity to the word, often with the descriptive force that gives the writing a visual impetus, say that those people and those environments appear before our eyes.

When you stop briefly for an opinion or analysis, which you place in the national and international background, it seems that the author has removed the nerve of electrification. For the aeration of the mind where my lungs were strained, before making a choice and maturing the vision, he likes to listen to the opinions of others, because: “How much people are in a hurry to make judgments”! But if the scales correct the measure, they do not alter the content of the attitude. Whenever he returns to the political formations and personalities of the time, he leaves neither the honor nor the harvest at the door, without giving the relevant facts. With this objectivity, Ejëll Çoba returns to himself, sometimes even laughing at the “bourgeoisie” of the knife and fork who, due to many years of academic training, may have previously lacked the practical sense of life, had naively believed and cleanly.

But this sincere self-portrait has a wide scope, it comes in the company of many unforgettable portraits. Even, written by a great heart, the book seems to become the mouth of the Albanian world. Although the conflict has a different nature, without the rumble of cannons, the cavalry and the field of Waterloo, although the binomial of war and violent peace is limited to prisons, then in another square – the field swamp of Maliq, due to cruelty and unusual number of characters the story takes some Tolstoy resemblance. Will be found in his pages from the names of the most famous personalities in our political history and that of letters (many of which are still publicly debated), to those of the lower strata, unfortunate and anonymous people who never again first their name is not written in the books. The portrayals are sometimes complete and sometimes quick sketches, but always with personal signs, often full of complexity, especially surprising when in this flow of characters unknown sides of them are discovered.

If we turn this book into a drama, with waves of arrests, images of terror, beatings, chains, electric shocks and pliers cutting off flesh, endless investigations and trials where executioners judge victims, dog shootings and macabre threats for the shooting, the drowsiness in the dungeons, and the inhuman exhaustion in the labor camps (like the Nazi lagers), all we had in the hall would have to climb on stage. But to take the place of the characters, maybe even that would not be enough. Through his drama, Ejëll Çoba has given the drama of his people, the mass persecution, the denaturation of the groove of historical development and the general tragedy that the bloody regime was bringing. That is why in that imagined hall, in the semi-darkness that has fallen from the extinguished chandeliers, the silhouette of the author appears to me as a shadow. Are you muttering a monologue after the capital sentence and ask what his condition is? Well, here is the text:

“I began to prepare myself spiritually. I thought of life as a film that suddenly breaks. I did not feel sorry for the world I was leaving: it seemed to me that I had known him well enough and that nothing new attracted me to deserve to know him. I was relatively young, 38 years old, and it seemed to me that I had not yet given my life as much as I could and should give. To the place where I was born, I was returning the task to life. ”

But he is not alone, crowded, the hall swarming with shadows. They are the veterans of the Anti-Communist Resistance. Meanwhile, we who have entered the top podium of the stage, we who have spoken in the pulpits (fff, the wind blows!), We who have conquered newspapers and screens, we who hold ourselves as heirs of democratic ideals, it seems that we have already we turned our backs. We know a lot to knock down, but we know a little to lift. And so, from short memory, forgetfulness often becomes haram to us. To date, the only worthy Monument dedicated to that resistance is the Memorial of the Resistance itself, and even this library remains the deepest and most moral trial of the dictatorship.

Every time I am in those gardens, where the silence is faint and the cypresses cast long shadows, it seems to me as if I hear a trembling gasp, coming strangely from somewhere: Save Our Souls! (Save our souls!) Then, in that harsh hesitation that gives you pain in the ribs, this thought comes to me: Who knows how many people live as dead among the living and who knows how many dead are still alive!

When at the fatal moment, on his way to Hadith, the faithful friend wanted to follow him back, Hamlet stopped him with a strict message, as if to take him out of the secrets of eternity. It is the paradigm that Father Zefi, our Plum, adhered to so sharply: Rrno just to show me. And Ejëll Çoba told us a lot and testified a lot, he fulfilled the centuries-old prophecy.

But on that mentioned day, the day his death was approaching (1979), the man who had been imprisoned for twenty-four hours for twenty-four hours in twenty-four years, seeing with his own eyes the grotesque of socialist reality, sank into disappointment. and modestly said of himself:

“They lost their lives.”

“No,” I reply to the dead, “perhaps a lost writer.”

But above all, above all, a Savior with his power, because you chose honor, Lord.

Ejëll Çoba

B U R G I M E T

Memoirs written from August 1973 to the end of December 1977

Only extreme things can be tolerated

Count Rober de Montesquieu

December 2, 1946, the first night I slept carelessly that I slept carelessly after two years. The serenity of death, like Serason’s first night in the grave. For two years the church stood day and night. My nerves were tired, I was shattered, not so much by taking care of myself, but by people: my mother, my sister, my brother. They had entered a forest, from which they were not enjoying the exit. All that was left was to go to Greece (we did not know that the Albanian-Greek border was occupied by the Greek communists), but spring or summer had to wait. It was a long wait. The node was resolved as by itself.

The greatest terror reigned in Shkodra. The cause was found in the Postriba Movement, or as it was officially called, the “September Events”. Movement without plan, without organization. Without being aware of the international situation, nor of the real internal situation, that movement disrupted work more than it could fix. Only the government that sought a reason to measure its pulse and act benefited from it. Such would have been many of those 200 uprisings that Albanians waged during the 500 years of Turkish rule.

Executions, imprisonments, tortures, were on the agenda, and as in any place and at any time, along with the most brilliant heroism that should not be forgotten, there were also betrayals, lawsuits, weaknesses, which caused misery. To escape torture, to alleviate suffering, or to reduce punishment, some said what they knew and what they did not know, and often found a follower.

The evening of the 2nd of Nandor, the day of many, began my ordeal, my slow death, which would last uninterruptedly until April 8, 1970: 23 years, 5 months and 5 days. A quarter of a full century, a life lost!

And I slept carelessly that night, I had no reason to think, my life no longer depended on me. Honor depended on me and for this I swore that I would protect him. I thought that the promise given to me that my surrender would not follow the family members who had sheltered me would be kept. But ten days later his brother, Kelin, was arrested.

It was rumored that in Shkodra more than 20 houses and assemblies had been turned into prisons for 2,000 prisoners. In one of them on Skanderbeg Street (which also had an entrance to Sumej Street, where today is the police headquarters), I was escorted by a partisan from the District Command, who was at Çurçia’s house. Fadil Kapisyzi, had escorted me to the district and shot me in an office where I was met on foot by a young officer, our nerves, dressed in military clothes, made of Italian fabric, who said to me: You will not suffer! ” And with a prominent Tuscan, he added: “We knew you in Italy”! When he saw that I was smiling, he continued to touch them somewhat: “But recently we found out that he was here”.

It was 9 o’clock in the evening when I entered a small room where there were four people. The captain assigned me a place near the window and the first message he said to me was:

- Do not look out of the window, because the outside guard is ordered to shoot me in the head.

It seemed to me excessive and naive zeal. Later prison life taught me that he had spoken only of threat.

When I glanced at those who would be the first companions of the calvary more than 20 years old, I saw two villagers, who were tied to each other by hand with chains. When they moved around the room or got up for any need, they looked like a feather to me. They were both Tak Filipi from Stajke and Idriz Vorfa from Sume. Suffering had bound the common destiny of those two wretches! Next to me was an anamalas who was sick with scabies. On the other side was a young boy, a citizen with glasses, Syri Anamali.

It was late and talks were not allowed. We spoke in silence. After a while, a guard came in again and tied the young boy by the legs, because his hands were tied. He tied me by the arms and legs.

When I opened my eyes in the morning and saw that the light had come out, I asked myself: what will the day be like in prison? When I looked around the room I saw that the others were awake and sitting still, I made sure I was not in the grave!

They untied us and took us home for the morning toilet. There I saw others, but it was strictly forbidden to talk to each other. Signs of torture were visible on everyone’s face and body. Cin Serreqi, his clothes and shoes were great. Only Guljelm Suma, somewhat familiar with the guards, spoke in a loud voice and did not address anyone and, as usual, joked enough to show that he had not lost his temper.

The friends ate what they had left over from the dinner and gave it to me. We started conversations and got to know each other.

Less than two weeks after I was delivered, one day when the food was brought to me, I saw that my name on the label was not written as usual with the writing of my brother, Kelly, but with the writing of my mother. I wondered: why did the brother and sister I had left at home leave my old mother with the label? I calmed down a bit thinking that maybe at that moment neither one nor the other had happened at home and my mother, in order not to delay the food, had sent it through another person without waiting for her sister. But when the next day I saw not only my mother’s handwriting, but instead of my name, my brother’s name, Kelly, then I suspected that he had been arrested. So I told the guard to take those sofratas and ask in the rooms if there was anyone with that name. Roja i morri. In the other room I heard the cry of Gjon Serreqi, who answered the guard:

- No Kel, yes you have Ejëll Çoba in the other room. The guard went from room to room, turned and said to me:

- There is no name for this – he left me the sofratas.

No matter how old she was, it was impossible for the mother to confuse the name of the boy in prison with what she had at home. The truth was that ten days after me, my brother, Kelin, had been arrested. The sister in those days had gone to Tirana to the other brother, to prepare the papers awaiting my transfer there.

After a few days I was taken to another room, where I found Ramadan Sokol of a mirditas. Ramadan had two very good qualities: one was that he sang beautifully, and this every time he was asked by a friend, even from other rooms, especially the song “Pëllumbeshë” which he had written and composed himself. The other was that he told in detail the many novels he had read.

I was trying to have a conversation with Ramadan during the day. He told me, not without some pride, that he had joined a group of young people, who had sought to remain neutral in the great chaos of the Albanian people. In the room where I had been with Ramadan Sokoli, they had brought Father Bernardin Palaj. From the door of my room I could see him and talk to him a little. He had on his forehead a large transverse Cham of a wound. He told me that my brother, Kelly, was in the section under torture. Stronger in signs than in words, it made me realize that the section was awful hell. Father Bernardini stayed a few days in the room with Ramadan.

One afternoon I heard noises and fairies on the porch and heavy legs sitting on the stairs. I looked out the window. I saw a brother holding hands and feet, whose cloak was being torn to the ground and brown paint was being applied. I knew him, it was Father Bernardini. They put him in a car. I could not explain what had happened to him. Ramadani explained to me that Father Bernardin had been summoned to the office to sign the investigation report.

He had wanted to refuse, but when the guard who had brought the minutes told him that if he did not sign it, he had the order to accompany him back to the section, he had put the signature. As soon as he returned to the room, he started punching her and banging his head against the wall. He had a heart attack. They came and took it. That same night, in the hospital room of the Toga prison, the former dormitory “Our Mountains”, had died. The light of tomorrow had found it thrown at the bottom of the garden over the manure. This is what the prisoners of Toga said.

After two or three days, they brought me to Padre Filip Mazreku. Although he had gone through some preliminary investigation, he was still under the influence of the quiet and monotonous life of the Assembly and dreamed of returning there to rest, away from the life of the section. I was told that when he was released from prison, he laid down his life and did not complain about his priestly life.

In the evening, the prison was filled with new, known and unknown guests. A new system was set up, and I was assigned downstairs to a large room with 56 people, most of them peasants who had been flooded by the flood and the revolution thirsting for blood and suffering. When I entered the room, I saw him lying next to the door, Father Karol Serreqi, who immediately called me and left a seat next to the door and told me to stay close. I said, “Yes, until they leave us!” I had not spoken to Father Karl since I was a child. He took the path of assembly since childhood and I the path of Italy. Life separated us, but suffering united us again!/Memorie.al

Continues in the next issue