Dashnor Kaloçi

Memorie.al publishes the unknown story of the former prosecutor Sokol Parruca, originally from the city of Shkodra, who after graduating with high results at the Faculty of Law in 1975, was appointed prosecutor, serving in the prosecution for many years in some districts of the country such as: Lezha, Tirana, Skrapar, Shkodra, Kruja, etc., up to the Supreme Court in the period 1991-1993. Rare testimony of former prosecutor Parruca, for some of his trials during the communist period, where he was forced to convict some citizens on orders from ‘above’, such as the case of Agron Belishova in the city of Lezha, or that how he refused to arrest a person who happened to be his childhood friend, until the refusal to sign the arrest of the pediatrician, Alfred Serreqi in 1987, when he was a prosecutor in the Kruja district. The sensational trials after the 1990s, when prosecutor Parruca released Ramiz Alia from prison, as well as former Democratic Party Interior Minister Ali Kazazi in 1997, signing his release from the courtroom, etc.

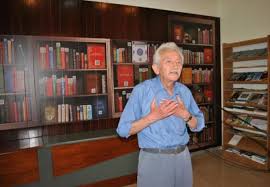

Although since 1999 he had opened a law office somewhere near his apartment in “Shallvaret” and practices that profession without much fuss and fuss as some of his colleagues usually do, his name is quite well known, especially after May in 1995, when he was serving in the Appellate Prosecution in Tirana and the opposition press of that time began to bend him more and more often, accusing him of being a lawyer of that court, he had become a lawyer of former President Ramiz Alia, ordering his release from the courtroom.

But former prosecutor Sokol Parruca, with a long career in the profession, denies the allegations. He says he has only enforced the law, as he did two years later with former Interior Minister Ali Kazazi detained over the Milot incident, which he also released from the courtroom. For all these attitudes held in the function of the defense counsel, he says that he has no remorse and is quite calm. If it were otherwise, he would not hesitate to apologize, even publicly as he did to some former political prisoners before the 1990s, who he says were unjustly convicted, by order from above. ‘. How he experienced these events of his career as a prosecutor and lawyer, introduces us to the exclusive interview for Memorie.al that we are publishing below in this article.

Mr. Parruca, what was the motivation for you to choose to study at the Faculty of Law?

In fact, after graduation, my preferences for high school were in the branch of Journalism and Philosophy, while Law, I had put the third in the application I made for the right to study. But the branch that I had put the third in my application, was approved and I gladly continued the Faculty of Law in Tirana.

How do you remember the beginning of your work in the judiciary?

It was very difficult, because from the faculty auditors, without doing any kind of internship, we went directly to the profession, to the courtroom.

What was the first case you were charged with as a prosecutor?

I still remember the first days of my work as a prosecutor in the Lezha District Prosecutor’s Office in 1975, but the first file I was charged with, I honestly remember, as it would not have been anything important, otherwise it would have been erased from my memory.

What about any other files you remember, from those of political punishments, such as “agitation and propaganda”, “attempted escape”, etc.?

I remember another file on agitation and propaganda with which a colleague of mine was assigned. That file was in charge of a young boy from the city of Lezha, who was arrested and taken as a defendant, after being accused of singing a very popular Italian song at the time. I told my colleague that the defendant should not be convicted, as he did not know the lyrics of the song he was accused of, and I sang the song to him from beginning to end. After that, I insisted and strongly influenced my colleague, that that boy be punished as little as possible and out of 10 years that was the article of agitation-propaganda, he was sentenced to only 3 years in prison.

When did you feel closer to your job before the ’90s?

There have been several cases, as our job as a prosecutor was not to distribute leaflets and decorations, but years in prison. I remember a case in 1984 when I was charged with arresting a person and when we went there to execute the verdict, I saw that he was my close childhood friend. I was horrified and cold sweat fell on me, so much so that the investigator and the police were not understanding who the prosecutor was and who was being taken as a defendant. I immediately went to the Prosecutor’s Office and asked that the case be handed over to someone else. And so, it was.

Were there cases when orders were given from above to punish a person?

There were many, but for me personally the first and last case was in Lezha when we convicted a person that he had beaten the party secretary. After that case, I was not given any more orders, as they considered me a liberal and not loyal to them.

During your career as a prosecutor before the 1990s, have you ever had your family, or relatives, intervene in a lawsuit to commute a sentence?

It has never occurred to me that anyone from my family or relatives would intervene in court proceedings, not even to discuss work problems with family conversations. But I remember a single case when I refused to sign the arrest of a person with whom we had family acquaintances. This happened sometime in 1987, when I was serving as a prosecutor in the Kruja District Prosecutor’s Office, I was asked to study a file brought to us by the “competent bodies” of Kruja, for the arrest of a pediatrician working in the city hospital of Laç. When I saw the file, I was surprised that it was about Alfred Serreqi (Minister of Foreign Affairs in the years 1992-1997) with whose family, we had an old friendship like the ones from Shkodra. Based on this, I refused to sign his arrest, arguing with the bosses that the evidence for his arrest was not convincing. They were even fabricated, under the pretext of a careless treatment of a sick child, but that was political. Of course, I could not say that. In fact, his arrest was required for reasons of family biography, as he had a runaway brother and a shot uncle, etc., problems of this nature, which were on file.

But after the ’90s, what were some of the important processes that you had as a prosecutor and what was your attitude towards them?

Among the most important processes I had after the ’90s, was that of former President Ramiz Alia, in 1995, when I was in the Appellate Prosecution in Tirana. After I was drawn to try Ramiz Alia, I looked at his file and concluded that he should be released, because the court of first instance had made a legal mistake, leaving him still in prison. The error of that court was procedural and he had come after miscalculating the serving of his sentence. Based on this, I requested before the Court of Appeals his release from prison and that court, supporting me, decided his release.

Did you have consequences after Alia’s release?

I had no consequences except for the pro-government press of that time, which attacked me harshly, accusing me of: ‘from prosecutor, I turned into Ramiz Alia’s lawyer’. This issue caused a stir and was analyzed by the highest authority of the Albanian judiciary, which concluded that my position was in accordance with applicable laws. This was made clear to the President of the Republic, Sali Berisha, and after that, I did not have any consequences either from him as Chairman of the High Council of Justice or from other superior bodies of Justice.

Did you not have any interference from politics, ie from the ruling party of that time, to condemn Alia?

I had absolutely no intervention. I did not have interference not only from politics, but also from the General Prosecutor of that time, Alush Dragoshi, whom I had a close friend from the time we worked together in Shkodra. Dragoshi never interfered with me, neither for Ramiz Alia nor for anyone else, which normally as friends we were he could do.

What about another sensational process, did you have?

In 1998, I had the case of Ali Kazazi, former Minister of Interior for a few days in ’97, who was arrested by the court of first instance, for the Milot event, where the late Azem Hajdari was also present. That trial also drew lots for me and after studying the file, I saw that there was no evidence of his conviction. Not only was there no evidence, but on the contrary, they were in his favor. After that I ordered his immediate release from the courtroom and the Court of Appeal was forced to release him against her will

Did you have consequences after the release of Kazaz?

There was a lot of noise and commotion from the left press, even calling me Berisha’s man. This probably came after a senior Democratic Party politician welcomed my decision on Radio Kontakt. This was the reason why, with the separation of the Court of Appeals in 1999, I was transferred to Shkodra. But due to the fact that with that city I had a lot of social, kinship, friendly and spiritual ties, and I would find it hard to work, I did not go. I was forced to resign, which was very pleasing to the Attorney General, and since then, I have continued to work as a lawyer.

Testimony of the former prosecutor, Parruca: “For years my conscience bothered me about the sentence of Agron Belishova and when we faced each other on the street…”

Rarely has any other prosecutor, judge, investigator or senior State Security staff dealt with political issues before the 1990s, former prosecutor Sokol Parruca, apologized publicly to the press for his participation in those processes. Conscious of the injustice done to the defendants, mainly those accused of political wrongdoing, however “in the name of the law” and by order from ‘above’, he did not hesitate to meet some of them to ‘I apologize. He has even done this since before the 1990s, when many of his colleagues did not even mention apologizing to his victim. If he understood that, the least his colleagues could say about him was: ‘After playing mind’. Regarding these, the former prosecutor Sokol Parruca, testifies exclusively for Memorie.al, saying: “I remember a case in Lezha, when a defendant from the village of Balldren was being tried on the charge: ‘Beating due to duty’. He had beaten the party secretary after he had caught him in the act with his wife. The whole court of Lezha wanted to sentence him severely, as he had raised his hand against the party representative. The trial against him was conducted by the President of the Court himself, while as the prosecutor of the case, I was in charge. Being young, both in age and in profession, I too joined the spirit of the court, remembering that we were serving the Party. And according to the order coming from above, that person was sentenced to 3 years in prison. A few years later, around 1987, when I was still working at the Shkodra Prosecutor’s Office, the case brought me to see that person somewhere on the national road, as he stopped cars at a checkpoint, which was made for the purpose of working with explosives. I told my driver to stop the car and I went out and apologized. He felt me and hugged me and said, “You had nothing to do, I have understood you since then in the courtroom.” There have been other cases of this nature, but what has tormented and eroded former prosecutor Parruca the most was the case of a former political prisoner, Liri Belishova’s brother, a former doctor who has long suffered in the prisons of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime. Regarding this case, Parruca states: “I was a prosecutor in the trial against Agron Belishova in Lezha, whom by order from ‘above’, we sentenced him to 10 years in prison. I was young then and I did not understand, we remembered that we were doing well and serving the Party. I felt I was wrong when we did the divorce lawsuit with his wife, there I felt very close. I have always had a guilty conscience about the man we had condemned in vain, albeit by order from above. “After the ’90s, I often exchanged with him on the street and I saw him face to face as if to apologize for that unjust action that we were forced to do once.” / Memorie.al

Curriculum Vitae

Sokol Parruca

1952 Born in the city of Tirana

1975 – Graduated from the Faculty of Law

1975 – 1978 Prosecutor in the Lezha Prosecutor’s Office

1978 – 1980 Prosecutor in the Tirana Prosecutor’s Office

1980 – 1982 Prosecutor in the Skrapar Prosecutor’s Office

1982 Deputy Prosecutor of Shkodra District

1987 – 1991 Prosecutor in the Kruja Prosecutor’s Office

1991 – 1993 Prosecutor in the High Court

1993 – 1995 Lawyer

1995 – 1999 Prosecutor in the Appellate Prosecution in Tirana

1999 – 2015 Lawyer