By Skënder Thaçi

It was the beginning of 1993, Albania had just begun to feel the smell of democracy, fear had begun to give way to fragile faith.

The movements inside the country were facilitated, my cousin from the village Sakat of Puka, Mani, meets me and tells me that he had been to Shkodra. Meeting people who had suffered under dictatorship was the first thing that witnessed the escape of fear between us.

He had met the famous priest, Dom Nikolle Mazrreku, a former political prisoner and interned for years, who had told him that he had been friends with Imer Imer. I had heard a lot about Dom Nicole from my family.

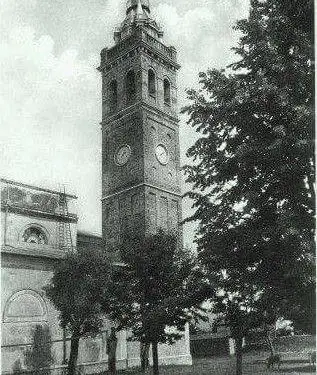

With one breath I left for Shkodra, I met one of the workers near the Great Cathedral and asked him to address me to Dom Nikolla, at first, he hesitated, but I insisted, saying: “Tell Dom Nikolla, that I am the son of Imer Thaçi (Imer)”.

So, he would not hesitate to meet me. And so, it happened. As I saw from a distance a man staring at us from head to toe, me and the friend who was accompanying me, he asked the worker, saying: who was Imer’s son?!

I headed towards him. He yelled, asking me to stop stepping. And he addresses me with these words: “You are a handsome boy, but you did not look like Imer. He was two palms taller than you, and you were holding him by the waist with both hands.

He spread his arms to testify to me how great he was as a physicist, describing a mountain knight. Then he hugged me with all his might and pushed me inside.

He told me: “Speak…”. He wanted to know everything that had happened to him about the life of his friend, Imer. The last meeting with Imer was after they were arrested on May 11, 1946, both together and convicted with the same indictment. Imeri was sentenced to 7 years in prison and Dom Nikolla to 5 years.

Their paths parted. Imeri escaped a little later from Albania towards Yugoslavia, while Dom Nikolla experienced the whole ordeal of suffering in prisons and internments, in various camps.

I told him about the liquidation of the father and his physical disappearance from the UDB, and about not finding his bones yet, even though we had asked for him a lot!

While he did not hesitate to tell me something he had not dared to say during the years of dictatorship!

Before we continue with the story of Dom Nikollë Mazreku and the story he told me, which prompted me to write these few lines as a sign of homage and respect to him, I am pausing to briefly go over who Dom Nikolla was?

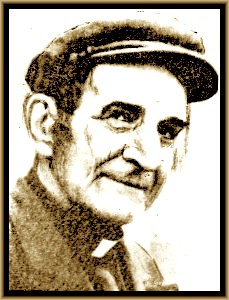

Who was Dom Nikoll Mazrreku?

He was born in Mazrek on December 28, 1912, was a researcher, writer, translator, polemicist, analyst, critic, etc. He completed his first lessons at the Saverian College in the city of Shkodra and in 1924, as a seminarian, he completed his high school education at the Classical High School, profiling himself in Philosophy. In 1932, he was sent to Rome, to ‘Propaganda Fide’, to study Theology.

On February 10, 1939, he was ordained a priest by Cardinal F. Biondi and after that, he returned to Albania, being appointed in the district of Shkodra, where he served in the episcopal cure of Sapa as chancellor. In 1939, he was appointed secretary of the Apostolic delegation in Shkodra, while in 1940, he was appointed as a parish deputy in the city of Tirana, where he carried out a lively activity, in the Parish Church and the Jesus Institute. As a beginner, he organizes a circle with young people of the “Catholic Action” Society, conducting many activities of a secular character.

During his time in Tirana, Dom Nikoll Mazrreku published a magazine for the protection of the nation’s rights, in response to the Italian occupation of Albania. In opposition to this, with the intervention of the high invading Italian authorities, in April 1942, he was transferred to the diocese of Sapa, as parish priest in Kryezi of Puka. After the end of the war and the coming to power of the communists, he was arrested by them in May 1946 and sentenced to prison, along with three of his friends, such as: Imer Imerin, Rexhep Zhuli and Qazim Bajrami.

He served his sentence in the Great Prison of Shkodra, as well as in the camps of Beden and Maliq, where he worked on opening drainage canals and drying the Maliq swamp. After his release from the first prison, he was sent to internment camps, such as in Kurvelesh, Tepelena and Berat, etc., from where he was released in 1956. After his release from exile, he was appointed parish priest in the village of Laç i Vau- Dejes where he served with devotion and rare dedication until 1956, when he was exiled for another 7 years, in the villages of Lushnja.

After spending ten years in exile, he was released in 1966 and returned to the district of Shkodra where he settled in a very hard job, as a manual worker, in the Brick Factory in Rrenc, Shkodra. He could not work there for more than a year, because in 1967, when the communist regime of Enver Hoxha started a brutal attack on religion and started demolishing places of worship, such as churches, mosques, monasteries, tombs, etc., he was arrested. Again, after openly opposing the actions taken by that regime and sentenced to 20 years in prison, which he suffered in Skrofotina of Vlora, in Reps of Mirdita, in Burrel, in Ballsh, again in Burrel, and finally in Zejmen of Lezha, from where he was released on March 17, 1987.

The painful story of Dom Nikoll Mazrreku!

I am continuing the story of Dom Mazrreku, who told me: “After my release from prison, (no time is determined) I return home and together with my mother, we started the search to find the remains of brother Rroku”. (He was shot on December 25, 1950, on Christmas Day in Kryezi, Puka, with a false accusation that he had allegedly tried to get a death sentence, named Fran Miraka, out of the hands of the State Security!)

“Our research was successful after several attempts, as an old woman helped us, guiding us where to look. We continued the search on a certain perimeter, stoning the place when we were looking, until we realized that the acoustic trail, we encountered something and not on empty ground. We opened the grave where the bones were. It seemed to us as if we saw our brother, Rroku, on his feet.

But we had nothing to see! Some bones tightened with barbed wire, as if they wanted to hinder the decay process. We took the bones, freed them from the shackles, put them in a sack to take with them, and reburied them in the backyard. My mother and I, so much so that we were freed from that grief, to bury him with dignity, so much so that we were sad about the way we found those bones handcuffed”!

After that short story, Dom Nikolla asked me to do the same for my father, Imer. But my story was different from that of Rroku, Imeri had disappeared from the Yugoslav UDB in the lands of Montenegro, but without an address and if I wanted to investigate, I would encounter the contempt and hatred of the unfriendly inhabitants, in that area of belonging Slavic.

Our conversations continued fondly that day, until the separation between us. A few years later, in the family of his sister, Marije Mazrreku Gjoka, in her house, on May 2, 1996, Dom Nikkola closed his eyes forever.

At the end of these lines, I wanted to remember that Dom Nikolla is one of the most suffering Albanian clergymen of all faiths, as he spent 25 years in prison and 12 years in exile. In addition to being a devout cleric and extremely devoted to the faith he represented and those he served, he was a staunch nationalist of the Albanian national cause, a high-class intellectual, a man of pen, author of several books, such as “Kanga për Gjergj Kastriotin ”,“ With the flags of the Kastriots ”, and“ We told the oak tree ”, as well as some other books, which he published under the pseudonym ‘Nik Barcolla’. Memorie.al