Dashnor Kaloçi

Memorie.al publishes the unknown story of professor, Fejzi Dika, the famous poet and translator who in the period of the Zog Monarchy graduated in Philosophy in Montpelié, where he lived in a room with Enver, but after the end of the War their paths were separated forever as Fejziu had anti-communist convictions and as a result, in 1983 when Enver sent Sulo Gradec to ask him to write memoirs about his period of study in France, he flatly refused. After that, as a sign of revenge, they arrested his son, Nils, and sentenced him to 8 years in political prison, and on the day Enver died, his wife, Nora Prosi Dika, was also arrested, after she dressed well and was painted with bright lipstick. the main boulevard of Tirana demonstratively….

Although Fejzi Dika had had Enver Hoxha as a classmate since high school in Korça and also during his studies in France, where they both lived in the same guesthouse for more than two years, Fejziu had no positive considerations for Enver. On the contrary, he spoke ill of his former classmate, saying that while they were in France, Enver did not study at all and spent all his time dealing with women. Fejziu also told us that Enver not only did not sit down to study, but he tried to make fun of his fellow students who sat all the time on books, telling them that they were crazy. Fejziu has told us these things since the time when Enver came to power in 1945 and when there was talk about him, he said: “I wonder how this person managed to come out at the top of the popular movement, and stay at the top of the state for several decades ruling dictatorially ”. In the early 1970s, Enver Hoxha, through the people who served near him, sent words to Fejzi, telling him that he was waiting for him in his office. But Fejziu had no desire to go and meet him, and he told them that he was ill and could not leave the house. After that, Enver sent Fejzi to Sulo Gradec, who told him if he wanted to write his memoirs about the period, he had been in France with Enver Hoxha. But Fejziu categorically refused to write his memoirs about Enver, saying he did not remember anything from that time. At the time we found out that Enver had asked for Fejzi, I immediately went to his house and told him: “Since Enver has asked to meet with all his old friends, go and meet him.” After that, Fejziu replied: “My Drita is staying because you do not know Enver Hoxha, I know him”. Tells for Memorie.al, Drita Dika (Morava) the daughter of the uncle of the former French professor Fejzi Dika, who tells the whole unknown story of her cousin and his relationship with Enver Hoxha, whom he had a classmate who from the Lyceum of Korça and for two years had lived together in a guesthouse in Monpelié, France.

What is the past of Fejzi Dika, how did he manage to graduate in France and what was his attitude, after returning to Albania during the Monarchy and during the years of fascist occupation? What were the reasons that he did not agree with the policy of the communist regime that came into force in 1945 and why he discontinued his passion for youth, poetry, and did not write any more verses until his death in 1983? How was he arrested in the bombing incident at the Soviet Embassy in 1950, and why did the Soviet ambassador intervene to secure his release? What was the French professor’s relationship with his former classmate Enver Hoxha and why did he refuse to write memoirs about him? Why Fejzi’s wife, Nora Prosi, came out with a red lip the day Enver died, and what was the answer she gave to the people of the State Security, who in revenge sentenced the boy to 8 years in political prison. Regarding these unknown stories of Fejzi Dika and his family, his cousin, Drita Dika, introduces us to her testimony, and attached to these testimonies, we are also publishing some of the autobiographical notes that Fejziu left written by hand. his.

Fejziu’s passion for poetry

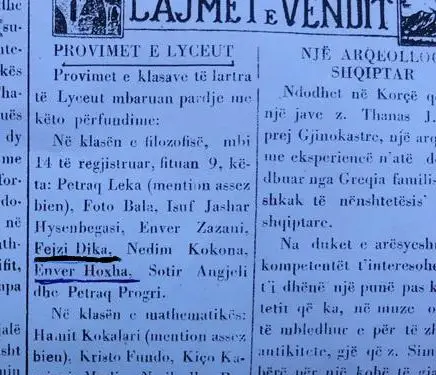

According to the testimonies of the relatives of Fejzi Dika and his close acquaintances, in addition to a natural ingenuity, he was also very studious, which was noticed in the benches of the Lyceum of Korça where he came out with high results and won the right to study in France. The period of his stay in France helped him in his further formation as an intellectual, as he, in addition to the field of Philosophy where he graduated, studied world literature and managed to get to know and master the masterpieces of that literature. But one of the greatest passions that Fejzi Dika had, was poetry, after which he excelled since he was in the Lyceum of Korça in the late ‘20s. In this regard, Drita Dika (Morava) testifies: “Fejziu exercised his passion for poetry during the years he studied in France, but the golden period of his creativity was in the 30s, when he started publishing his first poems in the literary newspapers and magazines of that time. From his first press releases, he became very well known as a lyric poet and critics of the time compared him to Lasgush Poradec, whom Fejziu had a close friend.

Parting with Enver Hoxha

Although Fejzi Dika had had Enver Hoxha as a classmate since high school and also in France where they lived for almost two years in the same environment, Fejziu had no consideration for Enver and their paths parted since returning from France. . Both during the years of the Monarchy and during the fascist occupation of Albania, unlike his friend Enver Hoxha, Fejziu did not interfere in politics at all, but he devoted himself only to poetry and studies in the field of Philosophy and Pedagogy. Although Fejziu had anti-fascist convictions, which is also evident from the testimonies of his relatives and the autobiographical notes he left written, he was also a staunch anti-communist. He maintained this position even after 1944 when the communists came to power and his former friend became the number one of the Albanian states. In this regard, his uncle’s daughter, Drita Dika (Morava) testifies: “Fejziu not only did not have any sympathy for Enver Hoxha, but on the contrary he hated him and wondered how that man with a weak character and morals , and with many shortcomings in education and culture, which had not opened any book in France, became the main leader of Albania. When Fejziu told us about the period of France, he often told us that Enver not only never sat down to study, but he despised them and tried to make fun of his friends, whom he called despots. He maintained this attitude towards Enver even when Enver came to power and never went to complain about the many injustices done to him. Since Fejziu hated the communist regime that came to power in 1944, he (second marriage) connected with the Prosi family, which was considered a bourgeois and reactionary family. In 1951, (after the first wife had an incurable disease and passed away) Fejziu married a young girl named Nora Prosi, although she knew full well that that marriage would further aggravate her position. his in the eyes of the regime in power. Nora came from a well-known aristocratic family, Prosi (who had the house where the National Museum is today) and her father, Athanas Prosi, had graduated in Dentistry and had a private clinic. At that time after the marriage, Fejziu together with Nora, settled in the houses of the Pros, because he did not have an apartment of his own in Tirana “, remembers Drita Dika (Morava) regarding the marriage of her cousin with Nora Pros.

Arrest for the Embassy incident

Shortly after her marriage to Fejziu, Nora Prosi was fired as the speaker of Radio Tirana, describing her as the sucker of a bourgeois and reactionary family. Regarding the vicissitudes that Fejzi Dika went through at that time, Drita testifies: who at that time gave private lessons of the Albanian language to some employees of that embassy. The day we learned of Fejziu’s arrest, my sisters and I were very upset and knowing his problems with Enver Hoxha, our minds only went bad. Since we did not have a brother and Fejzi was raised by our father Asimi, we considered him as our brother and he called us sisters. Fejziu was able to be released, just one day before the 22 arrested persons were taken to be shot, and this became possible only thanks to the intervention of the Soviet ambassador himself to Enver Hoxha, who guaranteed that Professor Fejzi Dika, could not have been implicated in dropping the bomb on their embassy. Had it not been for the Soviet ambassador, Fejziu’s shooting would have been inevitable, because in the group of 22 people who were allegedly implicated in the bombing, some of them had studied with Enver in France. On the day he was released, all of us sisters had come out to meet him in the center of Tirana, where “Kursali” was and as soon as we met, he told us: “I escaped this time as well”, Drita Dika remembers, regarding the arrest of Fejzi for the incident of the Soviet Embassy in Tirana in March 1951.

In the company of Lasgush Poradec

After the “bombing of the Soviet embassy” event, by order of the Albanian government, Professor Fejzi Dika was removed from that embassy where he was giving private lessons to some of its employees. This is also evidenced by the autobiographical notes that Fejziu wrote himself shortly before his death. At that time his wife Nora was also fired and their economic situation was quite difficult, as their first child, Edgar, was born. Regarding this, Drita Dika testifies: “After the two lost their jobs, Nora was forced to start sewing by car to cope with the living and difficult situation in which they found themselves. Fejziu also started to help him in that job, because at that time he was not allowed to teach private lessons in foreign languages. After some time, depending on the political conjunctures of the time, Fejziu was given the right to work as a professor of French in some of the gymnasiums of the capital. But even though he was allowed to work in education, Fejziu once and for all gave up his passion for poetry, because he could not agree with the spirit of socialist realism that at that time had plagued literature and all fields of art. In addition to his knowledge of World Philosophy and Literature, he also had extensive knowledge of painting, sculpture, music, dramaturgy, etc. Fejziu by nature was a romantic type, with subtle and very sentimental feelings. In those years he spent most of his time at home studying, or talking to my father Asim who had been a teacher. Although he was in a difficult economic situation, Fejziu kept to himself a lot. During the winter he came out dressed stylishly. When he left home, he went to the cafe “Kursal” where his old friends, Lasgush Poradeci, Skënder Luarasi, Petro Marko, Sterio Spase, Mal Osmani, etc. we’re waiting for him, with whom he had long discussions about Philosophy and Literature. “Apart from Lasgush Poradec, with whom he had an early friendship, Fejziu also had a close friendship with Professor Skënder Luarasi, with whom he spent most of his time,” Drita Dika recalls of his cousin.

He rejects Enver’s memories

The famous French professor and translator Fejzi Dika retired in 1967 after working as a literature and French teacher in some of the capital’s gymnasiums. Around 1973-’74, his former classmate, Enver Hoxha, who had started writing memoirs, remembered that one of his French friends who was still alive and could help him in that work was also Fejzi. Dika. In this regard, Drita Dika testifies: “In that period, through the people who served near him, Enver sent words to Fejzi to go and meet him in his office. But Fejziu had no desire to meet him and categorically refused, telling them that he was ill and could not leave the house. After that, Enver sent Sulo Gradec to Fejziu’s house and told him that if he had the opportunity to write some memoirs from France, where he had been with Enver. But again, Fejziu refused to write the memoirs, telling Sulos that he did not remember anything from that time. At the time we learned that Enver had asked for him, I immediately went to his house and said to him: “Fejzi, since Enver has met all his former friends in France, go and meet him.” After my words, he replied: ‘My Drita is staying because you do not know Enver Hoxha, I know him…! Fejziu had no desire to write memoirs about Enver Hoxha, because he had no positive considerations for him, on the contrary he wondered and told us how it was possible for a man who did not open any book in France to come to the top the Albanian state. “After Fejzi refused to write the memoirs, as a sign of revenge, his two sons, Edgar and Nils, were not given the right to continue their higher studies and they worked as workers in various companies”, Drita recalls regarding the refusal that Fejziu asked Enver Hoxha to write the memoirs of France and his revenge, leaving his two children without school.

Imprisonment of son, Nils

After living a life full of vicissitudes and incidents, Professor Fejzi Dika passed away at the age of 76, on January 16, 1983. Regarding his death, Drita testifies: “Although Fejziu and his family were looked down upon by the communist regime that considered them bourgeois and reactionary, at his death, in addition to us family members, were not absent and some of his comrades who were still alive. The last word on his body was given by Petro Marko, who spoke with superlatives about his former friend. Nearly two and a half years later, on the day the news of Enver Hoxha’s death was learned, Fejzi’s widow, Nora Prosi, after dressing well and applying bright lipstick, went for a walk in Tirana demonstratively to be seen. all. At that time Nora was well known by the Security organs, because her father’s family, with two brothers Serafini and Vlash were interned in Dumre. Likewise, her other brother Tonini (famous musician, the man who taught the accordion to Agim Krajka) after having spent ten years in prison, had fled Albania. Based on these, the appearance of Nora Pros with a red lip on the day of Enver Hoxha’s death, immediately caught the eye of the Security officers, who immediately arrested her, near the High Court and isolated her in one of her offices… There, the Security officers said to him: “Why don’t you mourn for Enver Hoxha, are you dressed like that and come out with a red lip?! “After that, Nora replied: ‘I am dressed as befits an intellectual and as for the mourning for Enver, let Nexhmija keep him mourning’. State Security released Nora because she was in her late teens, but she could not easily forgive him. “As a sign of revenge, they arrested the second son Nilsin, who was sentenced to seven years in political prison”, Drita remembers regarding the sentence of Fejziu’s son, because his mother Nora, went for a walk with painted lips, during the day of the death of Enver Hoxha. In the public cemetery of Tufina, where the body of Fejzi Dika is buried, according to the will he left, there is an epitaph written, where it is said:

I threw my body like a leaf

and stand as a free spirit

in any place in space

in the world without mystery.

Totally reconciled with life

traverse the whole universe

plant, animal and man

Now I live with the truth

I took the untouchable form

I found peace. ”

Who was Fejzi Dika, Enver’s friend who never agreed with him?

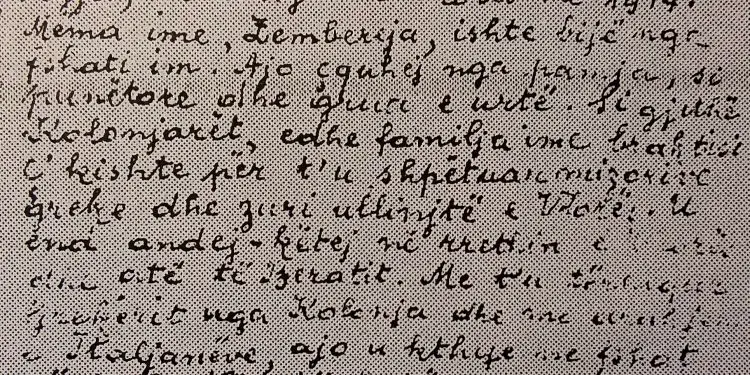

Autobiographical notes

I was born in Gostivisht of Kolonjë on December 15, 1907. My father Axhemi, the son of Aydin, was a devout Bektashi believer with a seven-year education. After my arrival in this world, he had two other children, a daughter and a son, who died young, in the olive groves of Vlora in 1914. My mother, Zembereja, was a daughter from the village. She was distinguished by her appearance, as a worker and a wise woman. Like all the colonists, my family abandoned what they had, to escape the Greek atrocities and took the olive groves of Vlora. He wandered here and there in the districts of Vlora and Berat. With the withdrawal of the Greeks from Cologne and the arrival of the Italians, he returned to the village in 1916. At that time my mother suffered greatly: She lived in a barn feeding on salted herbs with a handful of flour, to which she threw some drops of oil. The Spanish flu swept over my two parents and I was left alone in the middle of the road. A neighbor of my family sheltered me because he thus became the lord of the lands that belonged to me. I had two uncles: Ethem and Asim. One was in America, the other in the part of Albania occupied by the Austrian army. So, none of them could come to my aid. At the end of the war, Asim, who was a teacher, took me under his protection. He came to Erseka. I lived with him and under his leadership I started primary school five grades in 1921. I asked for a scholarship to continue in the Lyceum of Korça, which had a year that was open and preferred by all, because the professors were French and the textbooks were the same ones used in France. My prayer to complete my education went unanswered. I lived a year without school. The next year, my uncle, seeing me constantly upset, took me to Korça and let me live in the “Inn with two gates”, in a room with a primary school friend, and set me twenty francs as a monthly expense. That amount, in post-war hardship, was enough for a miserable living. I enrolled in Lice, in seventh grade. I worked hard and stayed in a good class, as I was given the honorary degree each month. During this time that I was continuing my studies at Lice, the principal, Mr. Leon Monbayrran, came and met me and by asking me in detail, he learned from me my miserable condition. He used all his authority with the Ministry of Education to grant me scholarships, and it worked. I was provided with boarding school living. I continued high school regularly until I finished. In September 1930, I went to France, to Monpelié, as a scholarship holder, to study history and geography. This direction of study was imposed on me, and I liked Philosophy. One year I attended the faculty in the assigned branch and the second year I entered the branch of Philosophy where I had good final results. But my initiative put me at risk of being awarded a scholarship. I returned to Albania, where, with the intervention of two people in good spirits and with an ardent recommendation of my professor of Philosophy, Marcel Foucault, I got out of this difficult situation. The Minister of Education, Hil Mosi, recognized my right to study in Philosophy, but conditionally, together with those of Pedagogy. That is exactly what happened. In August 1934, I returned to Albania. I marry a widow teacher, Bahire Kasimati, a peer of mine, drawn to her culture. In October, I was appointed professor of French language in Elbasan, where I teach sociology, as well as pedagogy. The invasion of Albania by the Italian fascist forces shocked me a lot. My wife and I left what we had, in order to leave the homeland because we were terrified of the foreign yoke. When we arrived in Korça, the border with Greece, which remained open for 24 hours, had just closed. We were forced to return to the top of the task. In December 1939, I transferred to the Lyceum of Korça as a professor of French and philosophy. The Italian-Greek war found me there. Two days before the entry of the Greeks into Korça, he and his wife fled in kidnapping, because I had alive their atrocities of 1914. After they were expelled from the territory of Albania, I took the place I held in Lice again and then they appointed me as a director. I did not like holding offices under the occupier at all. I struggled to get rid of the responsibility and achieved my goal by remaining a simple teacher. At the end of June 1942, my wife fell ill and I took her to Rome for treatment, where I stayed with her. After four months we came to Albania, where we found the transfer to Tirana. With the liberation of Albania, all teachers were considered fired. When the reappointments took place, I was appointed as a professor of French at the Vlora Commercial School. I refused to leave Tirana because my wife was still ill. I stayed without work for three months, then I was sent to Vlora mobilized. There I served the last three months of the 1944-1945 school year. The school year 1945-1946 was held at the Pedagogical School of Elbasan. I returned to the high school in Tirana as a professor of French. With the removal of French from schools, I was assigned to teach Literature at the Polytechnic “17 November”. There I had the opportunity to teach the Albanian language to four Soviet professors within a year. The success I had with them, made me be considered a person capable of learning Albanian to foreigners in record time, which provided me with a good future in addition to my salary. But Shemsi Totozani, Deputy Minister of Education transferred me to the Lyceum of Gjirokastra, in 1949, where I went as a mobilized. At the beginning of the 1950-1951 school year, I was notified of the holiday. I returned to Tirana, where I had a sick wife. After she passed away, I married Nora Prosi, whom I had met some fifteen months ago when she was a chorister at the State Theater. Now she was out of work just like me. Luckily, I was called to the Soviet Embassy to teach Albanian to some of its employees, paid by the hour. There I also started teaching French. I did this work with other Russians, who came to Tirana with service. The income from this job was three times that of a professor. But after three and a half years, with the change of all the staff of the Embassy, with the intervention of our government, I was fired, and I was left like a fish without water. My wife Nora, had opened a tailoring shop and had a lot of clients, I became her assistant in sewing, house cleaning and cooking, to escape manual labor. That way I lived a year and a half. We had a five-year-old son and were looking forward to the arrival and another second child. It was at this time that I got a job as a French translator in the Women’s Union Presidency. Intense workload and boredom made me sick: I started suffering from hypertension and heart. At my request, the issue of my employment as a professor was considered and I was granted the right to return to Education, after four years of work in the Presidency of the Women’s Union. Thus, I closed my activity as a professor, retiring at the age of sixty.

This autobiographical note that Fejzi Dika wrote to him shortly before 1983 when he passed away and left it in the care of his family, does not fully reflect the whole true picture of his life. According to the testimonies of his family and relatives, he has had a life full of suffering and vicissitudes. The rebellious French language professor Fejzi Dika, wanting not to bring trouble to the family, does not say a word in his memoirs about his former classmate, Enver Hoxha, which shows that he remained faithful to the word that had given himself up, not to write anything about it. In addition to his autobiography, he also left 99 poems in manuscript, with the trust that they be preserved, saying: “The time will come for them to be published one day”/Memorie.al