Dashnor Kaloçi

Memorie.al/ publishes the unknown story of Professor Miftar Spahia, originally from Kolesjani in Kukes, who fled Albania in 1946 and spent his entire life as a political asylum in the US where he received the title of professor teaching in Mansfield University of Pennsylvania. How he and the other Albanians who fled to Lavros, Greece, were trained by British Colonel Hill, who were the Kosovars who were sent on missions to Albania and the State Security people who penetrated there among the anti-communist exponents….

During our stay in the Greek camps, which were opened in cooperation with the Anglo-American allies for the political asylum seekers of Eastern European countries, the Albanian anti-communist diaspora was organized by the British for the introduction of various diversionist groups in Albania. All this was done with the support of British Colonel Hill, who was serving at the British Embassy in Athens. I personally met Colonel Hill several times in the years 1950-’51, when he often came to the Llaveros camp and was interested in finding people near the Albanian political diaspora, who were in that camp, in order to send them on missions. in Albania. Colonel Hill asked for our cooperation and we agreed to send groups to Albania. To achieve this, we connected with Baz Kupi who was in Rome. This is how Miftar Spahia, who lives in New Jersey, USA and originally from Kolesjani, Kukës, begins his testimony, during his last visit to his relatives in Albania. In his testimony, Professor Spahia tells all the events of how the Anglo-Americans helped the Albanian political emigrants, in the years 1945-1953 in Greece and Italy, to organize and intervene in the overthrow of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha. Who is Miftar Spahia, what is his past and what does he testify about the Albanian political diaspora in emigration? In this regard, he knows his exclusive interview, which we are publishing in this article for Memorie.al.

Mr. Miftar, after you left Albania and settled in the camps of Greece, did you ever discuss with other nationalist leaders the reasons why you lost the war and power fell into the hands of the communists?

During that time with the main nationalist leaders, such as Muharrem Bajraktari, etc., we often discussed politics and we all quietly accepted the fact that the communists won the war in Albania, because the leaders of the North were divided and the communist forces of Enver Hoxha , entered those areas without any great resistance. Likewise, it was tacitly acknowledged that the South of Albania bore the brunt of the war against the Communists.

Did you discuss Enver Hoxha and what was the opinion of the nationalist leaders about his figure?

We also discussed Enver Hoxha and we all agreed, considering him a very negative person. From that time, we all thought that Enver Hoxha was a man, in the service of the Slavs.

What about the Albanian Communist Party, in general, what was your opinion?

The Communist Party of Albania in our opinion had very negative considerations, after sending Shefqet Peçi and Ramiz Alia to Kosovo. That party sold Kosovo.

In the camps of Greece did you continue to engage in political activities, as you once did in Albania?

In the Llavros camp in Greece, where there were many Albanian political refugees, together with Dilaver and Fiqiri Dinen (former Prime Minister of Albania in 1944), I took over the leadership of the Legality Movement. Fiqiri Dinia had regular correspondence by letters, with Zog and Hysen Selmani. Zog was interested and often asked Fiqiri about the situation that prevailed there.

With which of the Albanian nationalist exponents did you continue to maintain ties in the Llavros camp?

I had a very good relationship with Muharrem Bajraktar. I also did very well with General Prenk Përvizi.

What about any other nationalist exponents you had friendship with at the time?

When I was in the Llavros camp, I also had a great friendship with Hamit Matjani. Hamit was not a man of great culture, but everyone loved and respected him, as he was very simple. Hamiti had a group of 10-15 people, with brave fighters like himself and with them he entered and left Albania several times.

In the camps of Greece, were there any attempts by the Albanian political diaspora to organize and intervene in Albania?

There were not only attempts but also organizations, which were made with the support of British Colonel Hill, who served near the British embassy in Athens. I personally met Colonel Hill several times, in the years 1950-’51, when he often came to the Llavros camp and was interested in finding people near the Albanian political diaspora, who were in that camp, in order to start them with mission in Albania. Hilli asked us for cooperation and we agreed to send groups to Albania. To accomplish this, we connected with Baz Kupin who was in Rome.

Who was the man who supported Colonel Hill the most, for the formation of groups that would land missions in Albania?

Colonel Hill, found the support of Asim Jakova, who knew English, after studying and graduating from Robert-College in Istanbul, Turkey. Asim was in the service of the Americans and worked for the good of Albania, making anti-communist propaganda. Along with Asim was Mehmet Agë Rashkoci from Kosovo, who found an Albanian and sent him to Asim, who himself was staying in Athens.

Were such groups formed that wanted to come on missions to Albania?

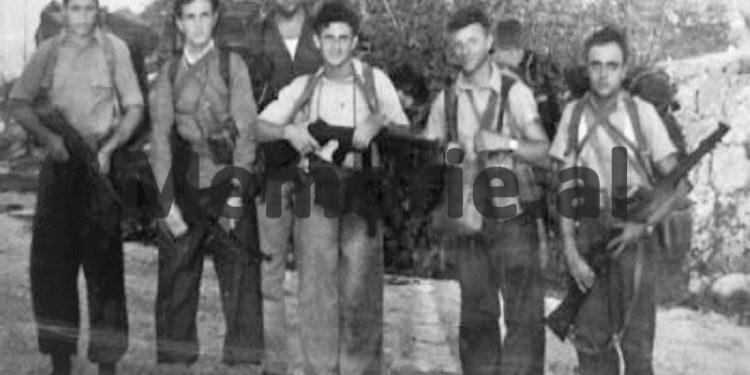

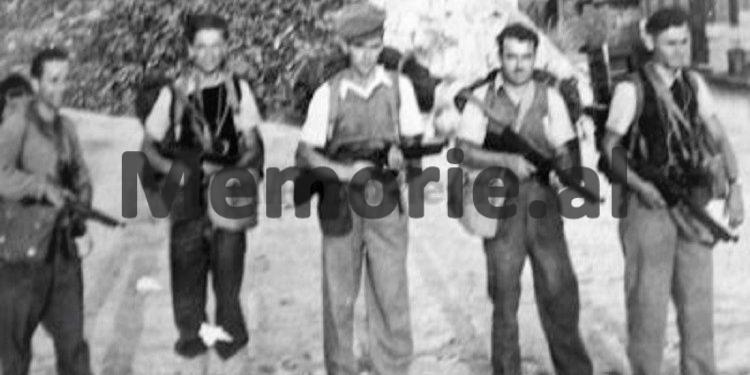

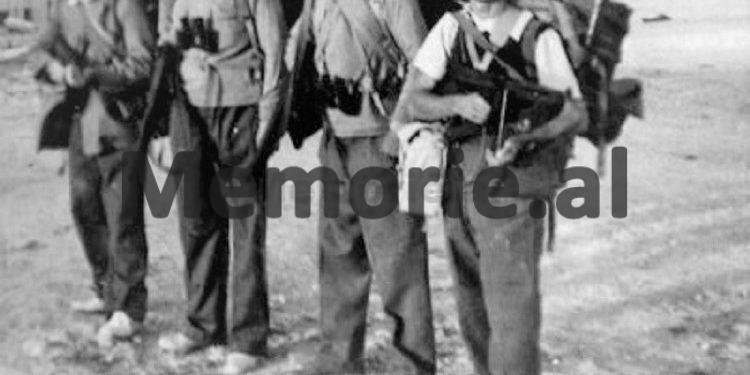

Asim together with Colonel Hill and the Americans trained and prepared in Crete and Malta a group of Kosovar patriots, who entered with missions in Albania. The group of Kosovars, formed by the Americans with the help of Asim Jakova, was initially sent to a camp in Crete, but one night they were attacked by the Greek communists and from that attack 14-15 Kosovars were killed. After that they were forced and transferred to the Llavros camp. All groups of Kosovars prepared by Asimi were physically annihilated in Albania and of them only Dali Vila from Luma survived.

After the Kosovar groups, were other groups sent to Albania?

Colonel Hill sent another group to Albania, which was able to escape alive from the pursuit of communist forces, only to land by sea. They returned to Greece, unable to carry out any mission, but at least saved their heads.

Did the Albanian State Security penetrate through its people in the camps of Greece, where the anti-communist political asylum seekers were located?

Yes, the Albanian State Security had sent to us his men and among others had also sent R.A., whose brother the communists had killed in Albania. We did not know that at the time and we knew him as a nationalist, but when he died, we found compromising letters in the safe and this was an unpleasant surprise for us. Likewise, another man we had in the Llavros camp was a…., Who was supposedly interested in the Albanians, but in fact he worked for Greece. I do not know how Abaz Ermenji with Petraq Ktona and Tako Baçi kept that man close.

When you were in the camps in Greece, did you have information about the situation in Albania?

We were more or less aware of the events that took place in Albania by people who fled and came to us there in the camps. When we were in Llavros, we also learned about Abedin Shehu, originally from Kukes, who was expelled from the Central Committee of the ALP.

During your time in Italy, were there organizations to bring landing groups to Albania?

Even during the time, we were in Italy, the Independent Bloc organized some landings in Albania, through some very good people, such as Alush Lleshanaku, etc., but all of them failed. The “Free Albania” Committee continued its activity in Italy, but that committee had no power, as everything was in the hands of the Anglo-Americans. In a word, without the help of the Anglo-Americans in Albania, nothing could be done. The Albanians had nothing left in their hands.

How did you analyze at that time all the failures of the missions that landed in Albania and the impossibility to overthrow the communist government of Enver Hoxha?

Since we were in Greece, for the situation that prevailed in Albania, we blamed the British and the disruption of Albanian nationalist groups operating abroad. Our evil was that Albanian communism was not independent, but was in the hands of the Serbs. Given this fact, when I fled Italy and settled in the US, I left politics altogether and devoted myself to history and literature.

Spahia, the “criminal” of the Kukes mountains who became a professor at American universities

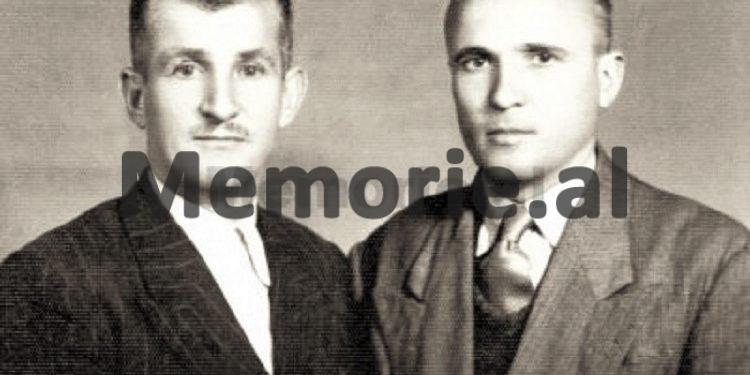

Miftar Zenel Spahia (Thaçi) was born on March 5, 1914, in the village of Kolesjan of Luma, in the district of Kukës. Miftari’s father is called Zenel Din Spahia, while his mother, Kadishe Hysen Osman Muçmata, was from the village of Shtiqën i Lumës. After finishing primary school in his native village, Kolesjan, Miftari came to Tirana in the dormitory “Vaso Pasha” and in 1935, he finished classes in the classical gymnasium. A year later, in 1936, he completed a military course at the officer training school in Tirana, receiving the rank of aspirant, and after that he was sent on duty to the city of Shkodra, to train recruits. In December of that year, Miftari received a state scholarship from the Ministry of Education, to pursue higher studies at the Faculty of Letters and Philosophy, University of Turin, Italy, which he completed in 1939.

He failed to get a degree in Literature, where he studied for four years, because two months before the exams all Albanian students of that university rose in revolts and protests against the Italian fascist aggression against Albania and because of this, the government the Italians interned them in Tripoli, Libya. In June 1939, Miftari returned to Albania, going to his hometown, Kolesjan i Lume, where he did not manage to stay long, because in November of that year, Miftari was arrested again by the Italians and brought to Tirana to was later exiled to Italy, to the prisons of Bari and Manfredonia, near the islet of San Nicola di Tremiti, on the shores of the Adriatic Sea. During the period of exile, Miftari made a request to the Italian Ministry of the Interior, which allowed him to take the diploma examinations at the Faculty of Letters in Turin, which he had left halfway through in the spring of 1939.

After graduating, Miftari returned to the place of internment in Tremiti, from where he was released in the autumn of 1941. After being released from his second internment, Miftari returned to Albania and the Ministry of Education in Tirana proposed him to serve as a teacher., where he wished. He chose Kosovo, where he served as a lecturer, in the gymnasium of Prishtina for one school year, as the contract was for one year. In March 1943 he was appointed deputy prefect of Rahovec and then Gjilan, where he remained until his arrest by the Italians in August 1943. After the capitulation of Italy in September of that year, Miftari returned to his hometown. where he stayed for a year, cooperating closely with nationalist forces operating in northern Albania.

In September 1944, he was forced to flee through the Luma Mountains as a result of the persecution of partisan forces marching into those provinces. In December 1944, the family of Miftar Spahia was interned in the castle of Berat, where many other nationalist families, one of the most famous in Northern Albania, were interned. As early as 1944, the communist government of Enver Hoxha included Miftari in the list of war criminals who were banned from returning to Albania. After staying for almost a year and a half fleeing through the mountains, falling several times in the struggle with the pursuit forces, in August 1946, Miftar Spahia, along with 56 other anti-communist people from Luma, Has and Kosovo, who operated under the command of Muharrem Bajraktar, crossed the state border and left for Macedonia.

Of that large group of fugitives, 21 were killed in clashes with Serb-Macedonian forces. Miftari with the others who survived, on September 7, 1946, entered Greece. From September 12 of that year until February 28, 1952, Miftari stayed in the camps of political asylum seekers, along with a large number of key exponents of the nationalist forces, who had fled to escape the persecution of the communists. On February 28 of that year, Miftari left Greece and settled in Rome, where he remained until November 1956, when he finally left Italy to emigrate to the United States.

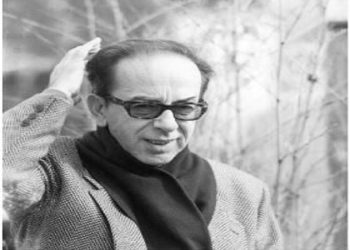

From January 1957 to November 1958, he worked as a clerk at the Columbia University Library, and from January 1959 until the summer of 1964, he worked as a lecturer at a high school. After this period of time and until 1980, for 16 years, Miftari worked as a professor, first at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, and then at Mansfield University in Pennsylvania. Since 1980, when he retired, Miftari lived with his family in North Bergen, New Jersey, USA.

After settling in America in 1956, he was constantly engaged in studies, being the author of a series of voluminous books, on the subject of literature as well as politics. In 2004 Miftari, was for a visit to Albania, to the family of Gafur Spahia (his nephew), who, together with the association “Luma”, organized the 90th anniversary of his birth and the promotion of some of his books, in one of the halls of the National Historical Museum./Memorie.al