From Namik Mehmeti

From Namik Mehmeti

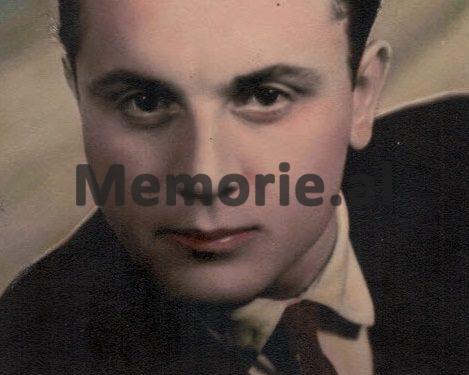

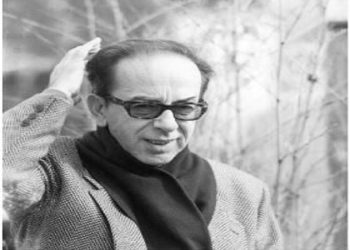

In Florence, I have known Mr. for many years. Agron Kallejxhiu, who in 1990, when the exodus to the gates of Prendimi had just started, at the age of 60, left Tirana, the city he loved madly, settling in Florence, Italy. Agron is 92 years old today, well maintained, and in perfect health. There is a past, as impressive as that that has left an indelible mark on suffering in the years of the communist dictatorship and now in the years of post-communism. Following the sentencing of his father, Masar Kallejxhiu, an intellectual educated in the years of the Zog Monarchy in Florence, Agron was also convicted on ridiculous and fabricated charges, ostensibly for a liberal life and as a young man.

What was the Kallejxhiu family in Gjirokastra?

Why did his grandfather Sabri Kallejxhiu become famous in the first patriotic groups that fought with rifles and feathers in Gjirokastra and in the South of Albania for the national cause and the independence of Albania? Who was Sabri Kallejxhiu and who were his friends?

Sabriu was born in Gjirokastra in 1859. He received his primary and civic education in his hometown and then continued in Istanbul, where he graduated from the “Sultanie” School with very high results. The newspaper “Bashkimi i Kombit”, in its issue of August 17, 1944, has given a wide space to the patriotic and educational activity of Sabri. The Society for the Printing of Albanian Letters was his refuge to make a contribution and to display patriotic feelings. Finding the support and assistance of his compatriots, patriotic intellectuals represented by Sami Frashëri, Ali Dervish Prishtina, Jovan Vreto, Pandeli Sotir Selcka, Naim Frashëri, Ahmet Kallejxhi, Said Toptani, Kostandin Kristoforidhi, Vaso Pasha, etc., by a member of Simply put, Sabriuit was entrusted with the task of the secretary of this society. He carried out many tasks entrusted to Sabri, to propagate the national movement in the various strata of the Albanians in Istanbul, by teaching in the Albanian language, and by distributing the primers printed by the Istanbul Society, with will and sacrifice. Even in Gjirokastra, when he returned from Istanbul, after being persecuted by the Turkish authorities, he did not limit his patriotic efforts. He brought the first primers to his city, openly expressing the desire to unite with the call: “O men, Muslim and Christian brothers, let us act and fight all together for the freedom of Albania and learn the sweet Albanian language, with it. written and read more. ”

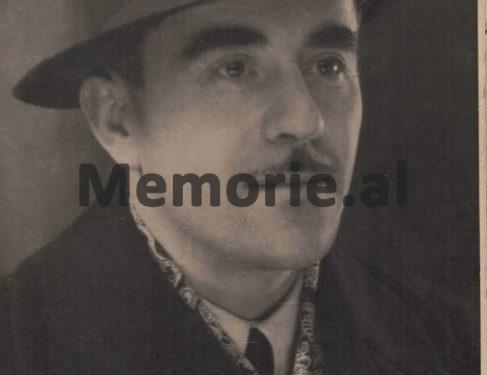

After that, he returned to Istanbul, as secretary of the society, sacrificing his life for the persecution of the Greek Patriarchate, which forced him to return to his homeland, being arrested as soon as he landed in Saranda, where he was imprisoned and after many struggles were released and settled in Gjirokastra. In 1898, Sabriu won a competition of the Ministry of Justice in Istanbul, being appointed in Meçova, as a questioner and then in Skrapar and Lushnje. With the Declaration of Independence of Albania on November 28, 1912, he was appointed by Ismail Qemali as a questioner in Durrës. From 1920-1924 he worked as an Albanian language teacher in his hometown. The Albanian government in 1924 granted him a pension, until the day of his death, February 7, 1929. He raised and educated five children, four of whom were educated in Europe, such as Masari, (Agron’s father) in Florence for Agronomy, Enver in a military school in Italy, Zehraja, for Obstetrics, at the Royal University of Studies in Bari, Italy (she was the first Albanian Muslim woman to graduate in the West) and Myzaferi, also in Italy for Agronomy. Sabri’s eldest son, Masari, and Masari’s son, Agron, experienced torture and suffering in the prisons of Enver Hoxha’s communist dictatorship, not recognizing any of the merits of this intellectual family in the service of the homeland. In an interview we did with Mr. Agron Kallejxhiu, exclusively for Memorie.al, we learned how he and his family were treated by the communist dictatorship.

Agron, you were one of the first Albanian emigrants to cross the Adriatic and come to Italy. Why did you choose the city of Florence as your second home?

Certainly a sense of debauchery for this city with great historical and cultural values, which emancipated European culture with its outstanding colossi such as Dante Alighieri, etc. But it was also a spiritual motive, as in this city my father, Masar Kallejxhiu, had studied Agronomy, defending with honors the diploma for ‘olive culture’. I remember like today when he spoke to me about this city, that in its center (today Piazza Repubblica) in a cafe called “Paskoëski” Albanian students gathered. Like my father Masari, other students who had received scholarships from the Zog Monarchy, who studied Political Science, Economics, Law, Agronomy, etc. In defending his diploma, his father was highly regarded, and university leaders insisted on keeping him, as a professor of this culture, olive, on their pedagogical staff. Even his Italian friends who had graduated from university with him, as well as many Italian families with whom he had befriended, insisted that Masari stays in Florence.

Was it just a feeling of patriotism or even a desire of his parents that Masari refused that invitation?

He did not forget the sacrifices that his father had made, for the national cause, for the Albanian language not only in Gjirokastra but also in other cities of the country. On the other hand, he saw it as an obligation to the Monarchy, as he was a worshiper and supporter of King Zog I, to contribute to the development and progress of the Albanian economy, especially in agriculture and in particular for the olive culture.

What was the course of Masari’s profession, after returning to Albania?

Initially, he started working in the Ministry of Agriculture, in the olive cultivation sector, falling down and up the villages of Albania, concentrating for months in Bushat of Shkodra. In addition to his passionate work and sacrifice on the ground, he gave his knowledge and experience in the magazine “National Agrarian Economy”, a scientific body of the Ministry of Agriculture, with many articles highlighting his professional and competent knowledge of the olive culture… Masari’s acquaintance with Dr. Bilal Golemin opened new avenues of work, where thanks to his support, the father worked with the same dedication even when he was appointed to the Prefecture of Tirana and again to the Ministry of Agriculture in the Central Directorate.

How did the Kallejxhiu family cope with the establishment of the communist regime in Albania?

He started treatment and recovery, where the target was Father Masari, who as a nationalist and supporter of the Zog Monarchy, despite his skills as an intellectual (he spoke three or four foreign languages), the contribution he had made to the development of the economy and agriculture in the years of the Zog Monarchy and then during the fascist and Nazi occupation, where he was only engaged in his profession as an agronomist, the communists targeted him and less than five months after the end of the war, his father was arrested.

What was the charge?

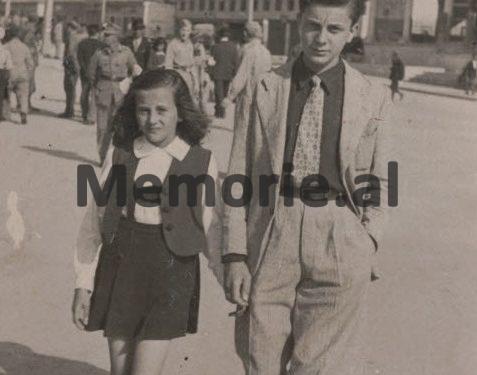

With the decision no. 96, dated 23.4.1945 of the Military Court, was sentenced as a war criminal to 10 years in prison. So there was no criminal activity, except that he sympathized with European culture and wherever he wrote and talked with friends and colleagues, he wanted Albania to be integrated into this culture. When my father was arrested, I was no more than 16 years old and I remember very well that the shock in our family was very great, as immediately the house raid by the State Security began. Equipment and valuables were confiscated, such as the father’s inherited library, enriched with historical, cultural, and professional literature. Many of his grandfather’s documents dealing with the national question and Albania’s independence disappeared. In addition to hard physical work, the mother had to take the roads of Albania to meet her father in the Burrel prison, in the labor camps in Maliq and Beden. My father wrote me letters and advised me not to fall into the trap of the State Security, which followed us everywhere. Her father’s sister, Zehraja, who had graduated in Italy as a midwife, the only doctor of this profession in the Municipality of Tirana, was forced to work outside Tirana, in Durrës, Delvinë and finally in Lezha, until she retired, earning the respect of the people of Lezha and the villages, starting from Pllana, Zadrima to the border with the villages of Shkodra. She sacrificed to give her two children a high education, where her son Apollon Gjebrea became one of the most famous doctors in Lezha.

Of Riza Kallejxhiu’s four sons, only Masari, was your father persecuted by the communist dictatorship?

The father was well known and had an anti-communist activity, a nationalist with Zogist convictions. On the other hand, he had a collaboration with Xhevat Kallejxhiu, the first cousin of our family. Xhevat’s activity in the service of the national cause, as a journalist and writer, was known everywhere by the Albanian nationalists. The exchange of letters with him, when Xhevati was stationed in America, the discussions on the unification of the Albanian lands with Kosovo and Chameria, the danger that threatened Albania from communism, were actualized and proven in the trial that took place against him.

After his release from prison, his father died quickly from ill-treatment and suffering in the prisons of the communist dictatorship, passing away at the age of 54, which our family had to sacrifice their lives for.

Surely a heavier burden would fall on you in the face of life’s difficulties?

My father’s and mine’s desire to continue high school remain just a dream. I started working at the Municipal Services Enterprise as a driver, where I was regularly monitored and monitored by the State Security. As a young man, born and raised in Tirana, I had acquaintances and friendships with artists, singers, and athletes. I also liked to follow the fashion in clothing, to associate with friends who had “stained” biographies and were monitored by the State Security. Dissatisfaction with the communist system was great, because in addition to the assets that had been confiscated from us, our house in the center of Tirana had been given to the chairman of the Tirana Executive Committee, Ndue Marashi, and all this was openly displayed to me.

Were you afraid of a possible arrest when you were drawn to a show punishable by a dictatorial regime?

The party organization in the enterprise had charged its people who were surveying, provoking me, even in foreign languages, as I spoke Italian and French. And at the age of 41, on August 1, 1970, I was arrested as I was entering the house. My investigator, Sali Budo, threatened to pressure me to tell who I was talking to against the “people’s power”, which was the anti-communist cell and who was running it! There was no evidence of hostile activity, other than my background as a Zogist family, a declassified class, and why I blamed the communist state for my father’s unjust punishment, without any concrete accusation.

How did the court hearing against you take place?

After three and a half months in the investigator’s office, on November 12, 1970, the trial of Shegushe Hakani and prosecutor Hava Bekteshi took place, where the accusation was summarized in “agitation and propaganda.” The sentence of 8 years in prison was demanded with the brutal behavior of prosecutor Hava Bekteshi. Even the appeal to the Supreme Court, after a month, upheld the decision of the Court of First Instance.

What about the punishment where you suffered?

First of all, I want to say that with these accusations, the family was ruined by the pressure they put on my wife and daughter to make the divorce a reality. Eight years in Spaç prison was a torment and sacrifice for my mother, while my young age, being physically strong, withstood the hard physical work, torture, and animal treatment experienced by prisoners in the depths of hell. After my release from prison, I started a new family. My wife from a nationalist family from Dibra, Teuta, had gone through the ordeal of suffering from the communist dictatorship, where her father, Ibrahim Tërshana, had spent eight years in prison in Maliq, Beden, Kavaja, working in swamps and swamps. While a cousin of hers, from the Tërshana tribe, Edip Tërshana, an ardent nationalist from Dibra e Madhe, was shot by the communist regime of Enver Hoxha immediately after the end of the War.

What about your life after prison, how did it go?

Of course, that was not easy. Relatives and friends distanced themselves, turned their heads, or made their way. Again, my biography came to the fore, wherever I looked for work, it became impossible. So I found the way to exile as much as possible, to find a peaceful life once again.

There are almost three decades of living in Florence. Of course, you have followed in the footsteps of life that your father, Masari, once refused the invitation of his Italian friends to stay in Florence, and now you are doing it as a family.

I’m definitely interested. I felt pleasure, even a privilege, that invitation that reached my address here in Florence. In 2009, the city of 1000 nurseries, Pistoja, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary (1909-2009) of the establishment of the nursery “MATI”, had organized a model party. The families of the students of 1930-1939, who had graduated in Agronomy, such as Lodovik Gajtani, Vasil Shqau, Jorgji Llavdo, etc., were also invited. On this holiday I was accompanied by the famous flower agronomist in Tirana, the late Thomson Nishani, who had known my father’s life from Italian literature.

Italo-Albanian Agron Kallejxhi, of course, has not forgotten Tirana.

I am repeating it once more. Tirana of the years of our youth does not return to today’s youth, as the capital is losing its identity. Twice a year my wife and I go to Albania, and we even celebrate the New Year with our grandchildren and friends who are returning from European countries.

Mr. Agron, thank you for this interview

Thank you.

Florence, June 2020

Memorie.al