By Petrit Velaj

Part Eight

Memorie.al / During the years of the Second World War, as if without realizing it, we were swept away by the waves of the Anti-Fascist War. We were classmates, as city boys – myself, Bajram Tushi, Hajredin Bylyshi, Hiqmet Buzi, Mumin Selami (Kallarati). Between dreams, desires, and the romanticism of literature. Many memories bind me to these friends of mine. Our parents, our mothers – honest and generous people. A patriotic mother, Mama Tina of Tol Arapi, the well-known patriot, used to gather us around her like a hen with her chicks. She was the mother of my youth companion, whom we called the “flower of Vlora’s youth,” Vllas Arapi. It seems to me that Mumin Kallarati gave Vllas this epithet. I associated with every friend and companion who was honest and sincere. This united us in our circle with peers like Hazis Sharra, Qemal Xhyheri, Xhemil Beqo, etc. Even though our opinions differed, we went on picnics, played games, and went to the cinema together. One meeting was held at Lef Sallata’s house. Suddenly, politicized thoughts erupted in our company. The debate flared up with the young revolutionary, Kastriot Muço. He was an honest man. After four or five days, Kastriot said to me: “Petrit, when will you hold the youth meeting in the Çerekçie neighborhood? In the city’s active committee, you have been elected head of the neighborhood youth group.” After a few days, we organized the youth meeting in the “Çerekçie” neighborhood.

Continued from the previous issue

The prison command approached somewhat, saying: “Look where he has ended up!” After this, Kadri Hazbiu summoned me to one of the prison offices. There, he told me these words: “Listen, Petrit, I am speaking to you as in our school and War years. I want to help. I propose that starting tomorrow; you come and work at the Ministry of Internal Affairs. This will make it possible for you to get out of here. We could even send you abroad for secret services. The work you do will serve the Fatherland, the Party, and your family…! I am clearing my debt to you. Give your answer now if you wish, otherwise, I can wait 3-4 days. What do you say?”

I smirked and retorted on the spot: “The path you have chosen is not worthy of me…!” And I did not prolong the conversation further, as I felt a great loathing for these snakes. Kadri grew angry. He stood up and, while walking away, let out some huffs, like a drunkard talking to himself.

With that, we parted. That night I slept late. Memories of the Commercial School years in Ujët e Ftohtë, the Anti-Fascist War, the national cause…! Friends and companions…! Only a few months had passed, and I could not get Kadri Hazbiu’s cunning out of my mind.

After several years, I was with many other prisoners at the labor camp in Tirana. I was working on the concrete pouring of a building in New Tirana (Tirana e Re). Kadri Hazbiu, who was inspecting the prisoners, stopped as soon as he saw me and asked from a distance about my health. He was dressed and covered in dust in his general’s uniform. With crude gestures, he turned to his companions, stretched his hand toward me, and said: “Once, this was my school and childhood friend. Now he has been reduced to this…”!

And he asked me: “Isn’t that right, Petrit?!” I left the concrete cart and answered calmly: “You are right, Comrade Minister. But inside this body dressed in these rags, there can be found national ideals greater than there” – and I pointed toward his body. I felt that he was keeping his nervousness inside. He came closer to me and, barring his front teeth cynically, asked me: “Petrit, who will live longer, me or you?” With my semi-silent nature, I replied: “Naturally, me!” Kadri turned completely dark and, amidst his rage, sealed the words that it was impossible for me to live longer. But I insisted: “Me, Mr. Minister, because I sleep peacefully every evening, for I think well of myself and of people. Whereas you, you cannot sleep, wondering whom you will arrest, whom you will harm…”! He did not prolong it further; I only remember him saying again that he would live longer because he was a minister and lacked nothing: “Petrit, you have your life in someone else’s hands!”

After some time, Kadri Hazbiu had gone to the village of Mavrovë in Vlora, to Sami Osmani’s house. His wife, Nazmia, is the daughter of my aunt, Sado. During dinner, as the conversation grew, Nazmia apparently asked Kadri Hazbiu: “Why don’t you release that cousin of mine who is languishing in Burrel? You were in school together…”! The Minister of Internal Affairs had reportedly given this answer: “With that head Petrit Agai has, he will rot there, in those prisons…!”

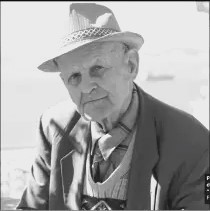

Toward the end of 1960, through my friend Ilmi Xhaferri, I received a telegram from my family: “Father passed away, December 20. Fehmi.” I grieved deeply for my father. The other prisoners found out as well. In the morning, they gathered in the prison yard and comforted me. This continued for a week. One evening, as I sat on my mattress, my dear father came to mind, and I composed these verses: “My father, like the oaks of Kanina / struggled through troubles and woes / he raised us mischievous children / with sweet words like noble hope!”

Time killed him and troubles aged him – his life bloodied under the dictatorship, his portrait always appears to me with the song of hope that remained on his lips! For days on end, I would sit and recite this poem to myself. Little time had passed since my father had come for the last time to Burrel prison. He came suddenly and unannounced, as he had come other times. The same had happened with my mother. I did not want them to toil on the long roads from the “Steppes of Vlora.”

His words, when we were to part, were: “Petro, my son, I always want you to be honest. My dear son, do not shame me. This is my wish and that of your mother, Feruze!” He left the prison bars, turning his head back once more. I knew that his eyelashes were wet with hot tears. From then on, that is how my father’s portrait appeared before me. A short time later, around 1962, my sister, Fatime, came to visit me. She told me that they had also imprisoned my other brother, Fehmi. The charge: “Agitation and propaganda against the Party and the People’s Power.” The sentence – ten years of deprivation of liberty.

Now, my mother Feruze remained alone with Fehmi’s wife, Hane, and their four-year-old son, Shpendi. During my twenty years in prison, my sister Fatime also suffered greatly. She was left without a husband, as Galip Haxhiu, her husband and son of the patriot Osman Haxhiu, had escaped abroad as early as 1944. She had three children, like doves: Mexhit, Pëllumbesha, and Napolon.

Fatime and Hane, who stayed close to the parents, helped me a lot in Burrel prison. Through snow and the scorching sun, my father, mother, Fehmi, Fatime, and Hane came to Burrel via difficult roads, and often night would catch them and they would sleep at the Bridge that leads to Klos. Even when Fehmi fell into prison, his wife would come to see me in Burrel prison. Also Bejxhe, Hulusi’s wife, when I was in Tirana prison, would come to visit me with food. She was accompanied by her young children: Bashkim and Vera. I could not bear to see the small children waiting for hours at the prison gate. I told my sister-in-law, Bejxhe: “Dear sister-in-law, I understand that something pushes you to come to me. Please, from now on, do not come anymore. I cannot bear to see the children in front of the prison wires…!”

A few months before finishing my sentence, around June-July 1964, they transferred me to the labor camp for the construction of the Superphosphate Plant in the city of Laç. There I began to learn and work in the profession of a rebar bender. The foreman of the rebar benders was a man of medium height, named Seit Coku. After two or three days, he came near me and, while I was bending a piece of iron, he said: “Do you remember me, Petro?!” I raised my head, looked again, and told him that; no, I did not remember. He explained that we had met over twenty years ago, in October 1944. He had been a platoon commander of the XXIII Partizan Assault Brigade.

It was he who accompanied me with the partisan squad to be executed at the Brigade headquarters. “It was your luck,” he told me, “that Professor Mihal Prifti came and ordered me to accompany you to the First Army Corps headquarters, on Dajt Mountain, to Hysni Kapo!” I cleared my mind and entered into a friendly conversation with him. Seit Coku was the brother of two martyrs killed in the Anti-Fascist War. He told me: “Someone slandered that I intended to escape, and so, here I am…!” I was observing him closely. He felt that I did not believe his word, so he added: “I swear by the blood of my brothers, I had no intention of escaping.” During the time I stayed there, I made him a friend. Memorie.al